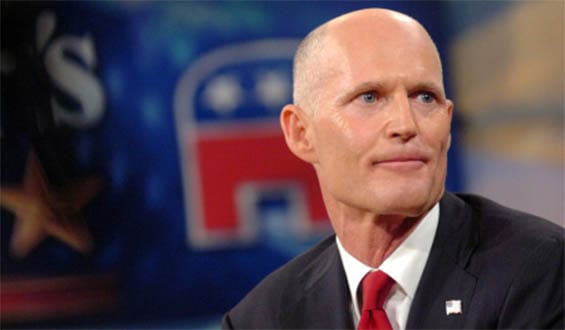

Rick Scott is right about Common Core standards. Photo from Education News. |

Just as Tony Bennett was talking to reporters last week about his new job as Florida education commissioner, Governor Rick Scott was getting some attention of his own for suggesting that all schools receiving public funding—including private schools accepting voucher-bearing students—should be held to the same standard.

Or, more specifically, the Common Core State Standards. And on this, reporters pounced, noting (with some jest) that Scott was parting ways with fellow Republicans who want to leave private schools alone and stirring backlash among private school leaders who feared they soon would have to “teach to the test.”

This kind of anxiety calls for a voice of reason, and Bennett is just the guy to provide it. After all, he’s leaving Indiana, where he pushed a voucher program that required students to take the same standardized test as do public schools (and where they also will be taking the Common Core assessments when those standards are implemented in 2014).

And the Hoosier State isn’t alone. Voucher and tax credit scholarship programs in Ohio, Wisconsin, and Louisiana require the same standardized assessments as those used in public schools. This does more than just make these programs more politically sustainable (though it does do that). It also develops a compact between states and private schools: autonomy for accountability. In other words, private schools are free to do what they like, but if they’re collecting public revenue, they need to be transparent enough to show that their voucher-bearing students are learning enough to meet standards that states say are important.

To be sure, Florida’s tax-credit scholarship program—the nation’s largest voucher-like initiative at 50,000 students—relies on more than just the marketplace to hold schools accountable. The state requires scholarship students to take a nationally normed achievement test (most take the Stanford Achievement Test), and the results are sent to a researcher who determines the overall impact of the program and of the individual private schools that have at least thirty testable pupils.

While research has compared the achievement of scholarship recipients with that of public-school pupils who take the Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test (and they have roughly the same gains), the taxpaying public would find it much easier to scrutinize the program’s effectiveness if all students were measured by the same yardstick. (Full disclosure: From 2009 to 2011, I worked for the nonprofit group that administered the tax-credit scholarship program.)

While reporters can find private school operators who will hyperbolically object to losing “art, music, chess all to worship at the altar of the state tests,” as one Tampa school leader said this week, they should also look to private schools that find a lot to like in the Common Core.

At least three Catholic dioceses in Florida, including the Archdiocese of Miami, are working to implement the Common Core standards (they’ve joined about a hundred dioceses nationwide that are doing the same). Many others are blending elements of Common Core into their curricula. And, regardless of what Governor Scott does, the seven Catholic school superintendents in Florida have directed the Florida Catholic Conference to talk with the state about allowing their schools to voluntarily partake in the Common Core-aligned assessments.

And if private schools are worried about losing their unique identities to state standardization, they have only to learn from efforts such as the national Common Core Catholic Identity Initiative, which involves the National Catholic Educational Association and helps K–12 schools integrate elements of Catholic identity—values, scripture, and Catholic social teaching—into curricula based on Common Core.

But if Florida follows the example of states like Indiana, will private schools flee the state’s popular voucher and tax-credit programs? If Indiana is any indication, the answer is no. Enrollment in the state’s voucher program doubled in its second year to 9,324 families, and the number of participating schools grew from 241 last year to 289.

Doubtless, Bennett will have other things to worry about when he comes to Florida, but we hope that enacting and implementing the governor’s worthy idea is one item on his to-do list.