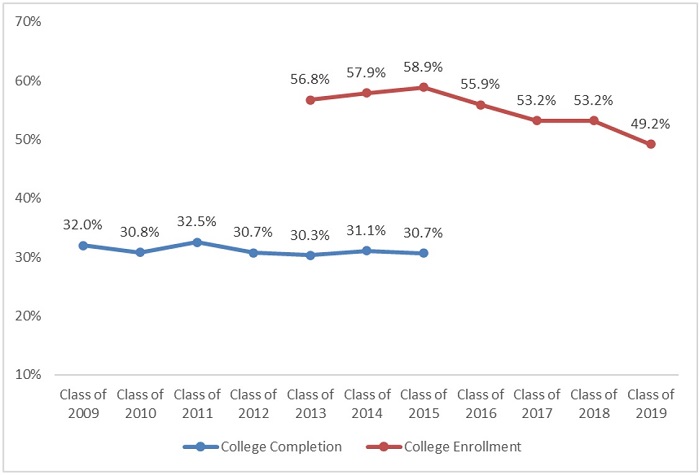

In November, the Ohio Department of Education released the latest college enrollment and college completion rates of Ohio’s high school graduates. Though following national trends, the data are eye-opening, as enrollment rates slumped below 50 percent for the first time since the department started reporting these numbers. Meanwhile, completion rates clocked in at a dismal 31 percent.

The figure below displays data on all the graduating classes for which the department has released data. The lag in reporting is due to the two- and six-year “lookbacks” (discussed in turn) for the college enrollment and completion rates, respectively.

- College enrollment is the percentage of Ohio students in a high school cohort—including graduates and non-graduates—who enroll in a two- or four-year U.S. college within two years of high school. Figure 1 shows that the high-water mark during this period was the class of 2015’s 59 percent enrollment rate. Since then, the rate has slid quite significantly, and just shy of half of the class of 2019 enrolled in college. The state hasn’t yet reported data for the classes of 2020–22, but we already know that college enrollment slipped during the pandemic. Thus, further declines are likely when data on those cohorts are released in future years.

- College completion is the percentage of Oho students in a high school cohort—including graduates and non-graduates—who earn an associate degree or above at a U.S. college within six years of high school. The completion rate has been historically low, as just 30 to 33 percent of Ohio’s classes of 2009 through 2015 finished a degree by age twenty-four. When data arrive on the classes of 2016 and beyond, the state’s completion rate could dip below 30 percent as we begin to hit the enrollment slide.

Figure 1: College enrollment and completion rates for Ohio’s classes of 2009–19

These raw data could be interpreted myriad ways, but here are my thoughts on these trends:

- Ohio should be working to increase the rate of completion among college-goers. While many factors contribute to dropout or elongated times to completion, the K–12 education system’s mediocre track record of readying students for rigorous college coursework likely plays a role. Data from the ACT, for example, show that just one in five Ohio students earn “college ready” scores on all components of the test. Even fewer students pass an AP exam before exiting high school (roughly 15 percent). In sum, the state’s high schools must do a better job readying students, particularly its high-achievers, for college success.

- Ohio needs to shine a light on the workforce outcomes of non-college-going students and non-degree-completers, alike. While we can be fairly confident that the 30 percent of Ohio students who earn degrees are on solid career paths, the whereabouts of the other 70 percent are entirely unknown. What happens to the students who don’t enroll in college? Are they in stable professions and starting to climb the career ladder? Or are most of them stuck in low-level jobs? How many aren’t in the labor force, whether voluntarily (perhaps to raise a child) or involuntarily due to employment challenges?

- The decline in college enrollment should raise questions about teenagers’ views on higher education and about colleges themselves. On the “demand” side, recent surveys indicate a slackening interest among teens in college. Why? Are students feeling increasingly unprepared for the academic load? Are they worried about rising tuition and student debt? Perhaps it’s more positive, and students are simply more interested in starting careers right away, as the “college-for-all” mentality has eased and more job opportunities materialize. On the “supply” side, the downward trend probably keeps college admins up at night, but it may also be an opportunity for higher education to retrench, slim down, and sharpen their focus on serving existing students. Doing so could put student needs more at the center of the higher education and might just put a dent in the enrollment-completion gap.

- Declining college enrollments—and low completion rates—should push high-quality career-and-technical education (CTE) further up the K–12 education agenda. Remember, a slight majority of Ohio students now choose not to enroll in college, at least not by age twenty, and an even larger majority don’t earn degrees. What are high schools doing to support their career goals? By the numbers, the answer seems to be too little. Less than 10 percent of Ohio students earn industry-recognized credentials before exiting high school, and some of those credentials appear to be of dubious value. The number of students who complete an apprenticeship or have meaningful work experiences during high school is unknown. Moving high-quality CTE and workforce development to the forefront is going to take serious work, requiring more comprehensive data and analysis, as well as significant policy reforms. It’ll also take a basic shift in mindset: Rather than college readiness being the “default setting,” many Ohio students would be best served if the state placed more emphasis on career preparation.

Most of all, the college enrollment and completion data remind us that higher education isn’t the only pathway that Ohio’s young people tread as they enter adulthood. Indeed, it’s no longer the pathway that even a majority of students choose after high school. While these trends could certainly reverse, retooling K–12 education to better balance the needs of college- and career-headed students is long past due.