Enacted in 2012, Ohio’s (well-named) Third Grade Reading Guarantee aims to ensure that children can read proficiently by the end of third grade. The legislation calls for interventions when students struggle to meet early literacy benchmarks, and it includes a requirement that schools retain third graders who do not meet targets on state English language arts exams or an alternative assessment. At the bill-signing ceremony, former Governor John Kasich captured the logic behind the law saying, “If you can't read you might as well forget it. Kids who make their way through social promotion beyond third grade, when they get up to eighth, ninth, tenth grade…they get lapped, the material gets too difficult.”

Despite the vital importance of early literacy, the reading guarantee has faced significant pushback from the start. Critics have attacked the policy as an “unfunded mandate,” and they’ve assailed the retention provisions as a form of punishment. The latter argument was recently echoed by a state board of education member who justified her opposition to raising the promotional score on third grade state exams by saying, “I don't think that anyone should be punished more than they already are being punished.”

What the critics seem to forget is the data showing that third grade tests scores are highly predictive of later outcomes. Kasich was right. Children who have difficulty reading early in life are going to face immense challenges in middle and high school—and likely into adulthood. That’s the real punishment.

The most influential report showing the link between early literacy and later outcomes is a 2011 Annie E. Casey Foundation study by Donald Hernandez. His work is based on the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth which tracked nearly 4,000 children born between 1979 and 1989 until age nineteen. That survey collected data on third grade reading scores on the Peabody Individual Achievement Test and high school graduation.

The results are startling. Non-proficient readers in third grade are four times more likely to fail to graduate than their peers who read proficiently. The odds of dropping out rise among non-proficient Black and Hispanic students who are a staggering eight times more likely to not graduate from high school.

Hernandez’s study tracked students who were in elementary school during the 1980s and ‘90s. Perhaps the link between early literacy and later outcomes has dissipated in more recent years. Or maybe state exams aren’t very good predictors of later outcomes.

In comes a new study by the University of Washington’s Dan Goldhaber and Malcolm Wolff and EdNavigator’s Timothy Daly, which shows that third graders’ state test scores still strongly predict high school outcomes. Their analysis relies on student data from Massachusetts, North Carolina, and Washington State that allow them to track academic progress from grades three through twelve between 1998 and 2013.

They find that lower third grade math and reading scores are associated with significantly lower high school math scores (results in English aren’t reported), less participation in advanced coursework, and lower rates of high school graduation. In terms of exam outcomes, the authors put the results this way: “All else equal, a student at the lowest percentile of the third grade math test distribution rather than the highest percentile is expected to be 48–54 (depending on state) percentile points lower in the high school math test distribution.” Depressingly, the relationship between third grade results and high school outcomes is nearly as strong as eighth grade scores, suggesting that very little “academic mobility” occurs between third and eighth grade.

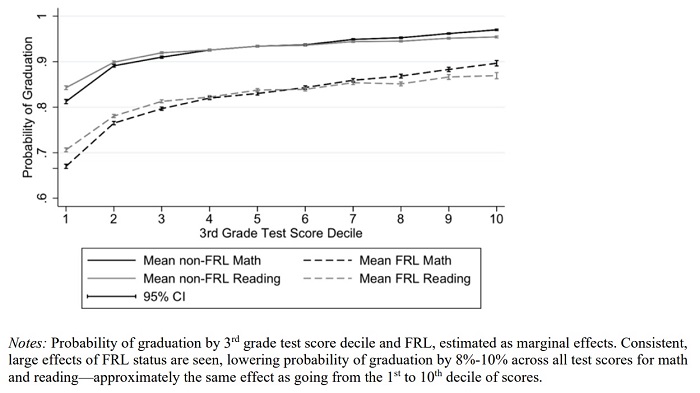

To illustrate the pattern visually, the figure below, taken from their report, displays the link between students’ third grade test scores on the x-axis and their likelihood of graduation on the y-axis. As is evident from the data points at the far left of the chart, students scoring in the lowest deciles—the first and second, especially—on third grade exams have much lower probabilities of high school graduation. For instance, for low-income students, defined by students’ eligibility for free and reduced-priced lunch (FRL), a widely used proxy for student poverty, the odds of graduation among those scoring in the lowest decile on third grade reading exams are about 0.70. That’s below low-income students who scored in the fifth decile, whose probability is just over 0.80, and far lower than high-achieving low-income third graders.

Figure 1: Probability of Graduation by third grade test score decile and FRL

Source: Dan Goldhaber, Malcolm Wolff, and Timothy Daly, Assessing the Accuracy of Elementary School Test Scores as Predictors of Student and School Outcomes, CALDER (May 2020).

Goldhaber and colleagues sum up their analyses with the powerful conclusion (emphasis added):

[E]arly student struggles on state tests are a credible warning signal for schools and systems that make the case for additional academic support in the near term, as opposed to assuming that additional years of instruction are likely to change a student’s trajectory. Educators and families should take third grade test results seriously and respond accordingly; while they may not be determinative, they provide a strong indication of the path a student is on.

State and local leaders in Ohio should heed the advice of these researchers and take third graders’ test scores seriously. This will be all the more important in the coming year, as students return to school having lost academic ground after being out of the classroom for an extended period. Although state retention provisions were waived for last year’s third graders due to the pandemic, schools must still step in and ensure that struggling readers receive the time and help needed to read proficiently. As the data indicate, these students can’t afford to get lost in the shuffle—a real possibility in the remote and blended-learning environments that schools are likely to use next year. Some critics will continue to wrongly decry such interventions as punitive. But let’s all remember that these steps are no punishment, but rather an investment in a child’s future.