The growth of private school choice programs in Ohio has clearly struck a nerve with the education bureaucracy. After rapid expansion in the number of schools slated to be deemed “low-performing” in 2020–21, which ballooned the number of students eligible for vouchers, choice opponents pushed for massive changes in Ohio’s EdChoice program. Their goal was to shrink the program, and before Covid-19 burst upon the scene, this effort dominated Statehouse debate.

In January and March, a couple of temporary measures passed that essentially kicked the can six months down the road without settling anything. Perhaps unsure of its legislative prospects and seeking to widen the battle, one prominent voucher critic, the Ohio Coalition for Equity & Adequacy of School Funding, announced last month that it will take to the courts to challenge the legality of EdChoice itself. No word yet on whether the suit will be based on state or federal law, though voucher advocates, mindful of the current composition of the U.S. Supreme Court—as well as past precedent, notably the Zelman decision arising from an Ohio voucher program!—are surely hoping to fight this suit in the federal courts.

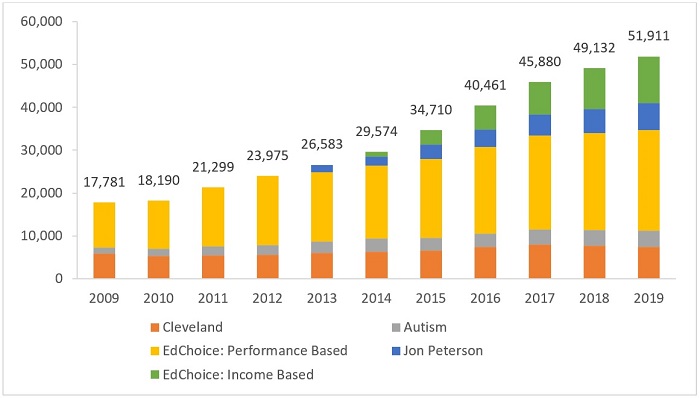

Why the renewed opposition to vouchers, which have been part of the Ohio education landscape for more than two decades? A part, but I think just part, was certainly the expansion of "voucher-eligible" public schools to 1200-plus, now all across the state, including some well-regarded suburbs. But it's not just kids getting EdChoice vouchers by virtue of attending ill-performing public schools. As we see in Figure 1, voucher use has been growing, year after year, tripling the number of participants over the last decade. The education establishment can't really be blamed for getting a little antsy.

Figure 1. Ohio voucher usage by program

The establishment arguments against vouchers, however, fall flat, at least as viewed by this public-school graduate and public-school parent. Here’s why.

First and foremost, when the government requires something of its citizens, as with compulsory education, as a matter of principle it should provide a wide variety of ways to meet the requirement. Between homeschooling, public charter schools, and open enrollment, there are more options available than ever before. Still, many of the options depend on where you live, and the open enrollment options are closed to many of our most disadvantaged students. Ohio has a vast array of private schools, some of which have served students for more than a century. Providing expanded access to them will give many families another way to comply with the state’s compulsory attendance requirements.

Second, we know that one size doesn’t fit all in education (or really much of anything). Yet we continue to assign most students to cookie-cutter schools based on their home address. We expect every local school to be all things to all kids. Then we act surprised when some students struggle. Despite the mounting number of such students, custodians of the current system seek to limit families’ alternatives, most especially when they include private schools.

Third, voucher opponents have spent more time inflaming public sympathies than making substantive arguments against vouchers. Consider the rallying cry that seeks to tie school choice to billionaires. With income inequality what it is, that naturally gets attention. But there’s no evidence that billionaires benefit from other families’ kids attending private schools. So why scapegoat them?

Fourth, opponents contend that vouchers don’t improve academic performance and that they sap traditional public schools of the capacity to serve the students who remain. It’s a powerful argument with obvious appeal. Yet there’s scant evidence that it’s true. Most rigorous analyses suggest that vouchers’ competitive effects—the impact on students who remain in public school—are positive. Participant effects—how voucher users fare academically—are more mixed but still mostly positive, especially if you consider long-term outcomes. If opponents are going to convince policymakers, they’re going to need data that actually support their assertion. Otherwise, erring on the side of liberty in the form of more educational options should continue to win the day.

Finally, when it comes to supporting students to attend private schools, the U.S. is a bit of an outlier—and not in the way you may think. In her report The Case for Education Pluralism, Ashley Berner noted many countries around the world that routinely fund private school education.[1] These countries often surpass the U.S. on international achievement tests. Thus, there’s every reason to think the U.S., if it chose, could devise a framework similar to that used in other countries getting strong results with both public and private schools.

***

While summer may provide a respite, the campaign against vouchers in general and EdChoice in particular will inevitably resume this fall. As we contemplate the claims and contentions of voucher opponents, let’s match them against these inconvenient truths.

[1] Like Berner, EdChoice has also documented the significant amount of private school choice available in other industrialized nations.