Just over a year ago, Congress passed the first of three emergency relief packages aimed at supporting the economy during the pandemic. The big-ticket items included massive amounts of funding for K–12 education. Ohio will receive a total of roughly $7 billion for schools, or about $4,000 per student, through the three pieces of legislation. The largest sums will arrive via funding streams known as ESSER II and ESSER III that were included in the two most recent packages. Save for a set-aside for the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), the vast majority of these dollars go directly to school districts and public charter schools. They have through fall 2023 to obligate these funds and may spend them on a wide range of activities.

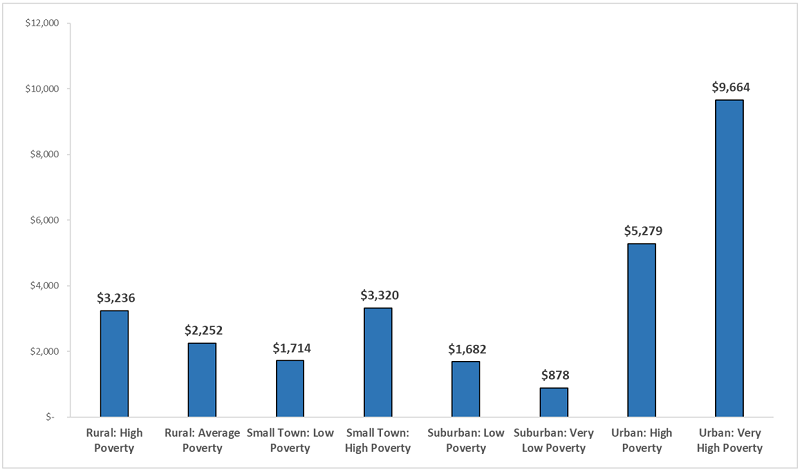

To allocate dollars, federal lawmakers required the use of Title I formulas that generally steer more aid to high-poverty districts. That’s sensible, as low-income students have likely been most impacted by the pandemic. But it is worth noting the significant concentration of funding in high-poverty urban districts. The Ohio Eight districts, which include Cleveland and Columbus, receive amounts that average almost $10,000 per pupil; these are the “urban: very high poverty” districts in Figure 1 below. Meanwhile, other districts receive more modest sums. Lower-wealth rural and small town districts, for instance, receive approximately $3,000 per pupil, while wealthier suburban districts receive around $1,000 per pupil. Interestingly, one of Ohio’s largest suburban districts—Olentangy—gets zero federal relief dollars.

Figure 1: Average per-pupil ESSER II and III funding by district typology

Source: Ohio Legislative Service Commission. Note: Chart displays an average per-pupil funding (weighted by each district’s enrollment) from the ESSER II and III relief packages by ODE’s district typologies.

While Ohio policymakers don’t have control over how most ESSER dollars are allocated, they can work to ensure that these funds are being used appropriately. That goal is important for two reasons. First and foremost, the aid is supposed to help students recover after much disruption to their education. Given that pre-existing achievement gaps have likely widened due to the pandemic, it’s especially critical that high-poverty schools use these funds wisely (and that ODE target its funds effectively). Second, much like its oversight role in federally funded programs such as unemployment insurance, the state has a responsibility to the taxpayer to be transparent about how schools use this public money, and to help guard against abuse.

To their credit, lawmakers in both the Senate and House are considering ways to create more transparency and accountability for these federal funds. Consider the provisions in two similar pieces of legislation that were introduced earlier this spring—HB 170 and SB 111 (neither have been enacted).

- Fiscal transparency. The Senate legislation contains an important provision that would create more sunlight and accountability around the use of these dollars. Specifically, it requires ODE to submit reports by December 2022 and 2023 that detail how schools are spending these federal dollars. This is crucial because, right now, all we know is the dollar amounts that schools receive. For example, ODE reports that Columbus City Schools received $31 million in CARES Act funding—the first of the relief packages. What we don’t know is how the district is spending those funds. On summer programs or tutoring? Salary increases? HVAC systems or new busses? This reporting requirement would also shed light on how ODE is using its funds and how the governor’s office is spending the modest amount of aid that it received to spend on education.

- Legislative check on ODE spending. As already noted, ODE also receives a portion of the relief aid through set-asides allowed in the federal legislation. Specifically, all three packages permit state departments of education to reserve up to 10 percent of the total amount of ESSER funding to use for centralized activities. In Ohio, that amounts to somewhere north of $500 million available for ODE—a sizeable pot of money that it can generally use at its discretion. The House legislation includes a check on how ODE uses these dollars by explicitly requiring the department to seek lawmaker spending approval through the state’s controlling board. This oversight mechanism could discourage poor uses of these funds, and it may also create an avenue for legislator input into the agency’s spending decisions.

- Protecting against abuse. Despite the good intentions of the relief programs, there have also been cases of fraud, especially in the paycheck protection and unemployment programs. Although education funds may be less susceptible to abuse, it’s not unheard of for schools to mismanage money. Both Senate and House bills wisely include provisions that allow the Ohio Auditor of State to look into the spending of federal education relief dollars, whether they are being spent by ODE or Ohio schools. The threat of a potential audit could curb questionable spending—things like sweetheart contracts or deviations from spending rules. The provisions would also allow the auditor to investigate concerns and likely issue findings for recovery if instances of abuse are uncovered.

Finally, while not a part of either HB 170 or SB 111, state policymakers should consider one additional measure: Evaluations of schools’ federally funded recovery initiatives. This would increase our understanding not only about how these dollars were spent, but how effectively they were deployed. For instance, as my colleague Jessica Poiner recently highlighted, Columbus City Schools is planning wide-ranging summer programs that are almost certainly being supported to some extent through the relief aid. It’s one thing to know that the district is using the funds to support summer learning, but it’s even more critical to gauge whether these initiatives are making an impact. Good research would help answer questions like how many students participated—and how many did so consistently. Did the summer programs boost learning outcomes or improve other indicators of children’s well-being? It’s true that these evaluations won’t be able to inform immediate spending decisions. But solid, independent research would provide valuable information about the return on these investments, and help guide future decisions about whether to scale up, modify, or wind down schools’ recovery initiatives.

* * *

A significant amount of federal funding is pouring into Ohio schools, with the largest portions going to high-poverty districts. These dollars are of course temporary but they should assist in the efforts to help students regain lost ground. Much, however, hinges on whether schools use these dollars in an effective manner. Of course, state lawmakers need to continue to insist on accountability for student outcomes. To that end, the state should reboot its report card system as soon as possible. Beyond that, however, a little extra oversight around spending these funds wisely could further ensure that students reap the benefits.