A basic principle of school funding is that dollars ought to follow students to the schools they actually attend. Funds shouldn’t be directed to the schools that children attended last year or the year before. That’s because the schools serving students today bear the responsibility—and costs—of educating them today.

Another precept of school funding is that state dollars should be targeted more heavily to districts with lesser capacity to generate funds locally. Almost everywhere, Ohio included, state policy establishes a baseline per-pupil funding level throughout the state but the funds themselves are mixture of state and local dollars. Where a locality has limited capacity to raise funds through taxation—low property values, for example, or concentrated poverty among residents—the “state share” should increase.

Ohio has long struggled to follow these principles and ensure that funds flow strictly through formulas that are predicated on current enrollments and measures of local wealth. One major obstacle has been legislators’ repeated practice of enacting “guarantees” that provide districts with excess funds when their current formula prescriptions fall short of their previous funding levels. This situation typically occurs when districts are losing enrollments and/or increasing in wealth—and thus in less need of state aid at the present time according to the formula.

While politically popular, these guarantees—sometimes called “hold harmless” provisions—have serious downsides. For one, they short-circuit the state’s own formula and provide special subsidies for certain districts. (It’s not wrong to call them a form of “pork barrel” politics.) That’s unfair to the districts that are funded strictly via formula or those that receive fewer dollars than their formula prescriptions through the use of caps. Such caps, the opposite of a guarantee and also long employed in Ohio, limit funding increases called for by the formula when districts have growing enrollments and/or declining wealth. Guarantees are also unfair to taxpayers, who foot the bill for the inefficient spending. They are, in short, like paying unemployment benefits long after a person has found a job.

Ohio’s new funding formula, which first went into effect in 2021, rightly promised to move away from guarantees. In fact, one of the “critical values” undergirding the model is that “dollars flow directly to where students are educated.” Early projections from advocates indicated that one in six districts would remain on a guarantee during the transition to the new system (down from more than half). One school group official predicted that, over the longer haul, “a need for a guarantee should go away.” But how well is the new formula actually accomplishing this? Is the model moving districts off guarantees, as it was intended to do, and solely onto the formula?

Let us first understand that the new formula included at least three guarantees of its own.[1] Despite their labels, legislators didn’t specify any sunsets or phase-outs of these funding streams, and the introduced version of this year’s state budget would continue them into the next biennium—again, without an expiration date.

- Temporary Transitional Aid: Guarantees that districts do not receive less state funding than in FY 2020.

- Formula Transition Supplement: Guarantees that districts do not receive less state funding than in FY 2021.

- Supplemental Targeted Assistance: Provides certain districts extra dollars based on their FY 2019 enrollments. Though not technically a “guarantee,” this funding stream functions like one by providing a special subsidy for districts that have historically lost enrollments as students exited for charter and private-school options.

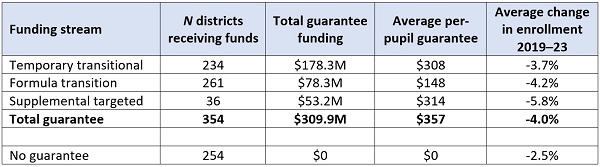

Table 1 displays an overview of these guarantees. In FY 2023, more than half of Ohio districts—354 out of 608—are on at least one guarantee (some are on multiple). In total, these “outside-of-the-formula” funding items cost the state nearly $310 million this year, or $357 per pupil. While not an astronomical sum in the context of the full state budget, this is more than the $160 million that the state spent this year on career-tech, English learner, and gifted categorical funding combined. In comparison to 2018–19—the last year that the old formula was used—slightly more districts are on a guarantee today: 354 versus 335 districts in FY 2019. The total cost of guarantees has also risen from $257 to $310 million.

Table 1: Breakdown of guarantee funding for Ohio districts, FY 2023

This lack of progress on guarantees—and even some steps backwards—seems to boil down to three factors:

- Most obviously, they are still included in the new funding system. Back in 2021, lawmakers likely felt a need to protect districts from any abrupt funding cuts caused by structural changes in the formula. That was probably fine. But these guarantees were supposed to be “temporary” and “transitional.” Yet now, under the governor’s proposal, they will continue in FY 2025 and 2026, and there has been almost no talk of phasing them out or removing them.

- The recent slide in district enrollments has also been a factor. This trend means that the formula—as it should—yields lower funding totals for some districts than in prior years. As Table 1 indicates, districts on a guarantee tend to have larger enrollment declines from 2019 to 2023 than their non-guarantee counterparts (-4.0 versus -2.5 percent). In a system that shields declining districts from funding reductions, we’d expect this pattern. East Cleveland, the state’s largest beneficiary of guarantees, is a vivid example. Over the past four years, the district lost a staggering 24 percent of its enrollment.[2] Under a rational, enrollment-driven formula, East Cleveland should have its funding substantially reduced. But instead, the state propped it up with an additional $3,364 per pupil in guarantee funding this year.

- Increasing local wealth has also reduced the formula amounts of some districts, which the guarantee then overrides by providing excess funds. The impacts of increasing wealth, however, are made worse by the mechanics of the new formula, which (as discussed in another piece) does a poorer job than the prior formula in controlling for system-wide inflation in property values and incomes. In fact, a recent analysis from the state’s Legislative Service Commission projects that, due in part to continuing increases in local wealth,[3] “temporary transitional” guarantee funding will skyrocket from $178 to $554 million by FY 2026.

Touted as the “Fair School Funding Plan,” the new state funding formula was intended to create a more even playing field in which the vast majority of Ohio school districts would be funded on the same formula. To achieve this, the plan promised to move away from guarantees. But the results thus far haven’t turned out that way. As the budget debates continue this spring, lawmakers should begin asking more questions about why this is happening—and what steps might be needed to correct course.

[1] There is also a guarantee within the transportation formula, a staffing minimum guarantee inside the base cost formula that benefits low-enrollment districts, and a guarantee that provides high-wealth districts a minimum amount of state aid.

[2] East Cleveland’s wealth did not increase from 2019 to 2023, so its guarantee funding is being driven by enrollment declines (perhaps even predating 2019, as past guarantees pushed its funding upwards).

[3] In a complex issue, LSC notes that the increased guarantees are also related to the continuing phase-in of the new formula proposed under the governor’s plan. For most districts, the phase-in increases their funding to more closely meet the formula prescriptions. But for some districts—likely those on a guarantee—the phase-in is actually a “phase-down” from higher historical funding levels to the lower current prescription. A higher “phase-down” percentage would thus increase their guarantee funding.