An alternative proposal for high school graduation requirements

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Last year, the state legislature followed a recommendation made by the State Board of Education and created a series of alternative graduation requirements for the class of 2018. These alternatives were far too easy and allowed schools to graduate students who were not career and college ready.

A few of the alternatives were particularly bad. For instance, one requirement allowed students to graduate if they had an attendance rate of 93 percent during their twelfth grade year. In the district where I teach, I know that even though many students would show up late and leave early, adults wouldn’t mark them absent out of fear of eliminating the attendance graduation alternative. It’s bad enough that data weren’t tracked reliably. But missing what amounts to thirteen days a year also doesn’t add up to creating a career- or college-ready student. Instead, it rewards students for doing something that we should already be expecting them to do.

Another example is the requirement that allowed students to graduate if they completed a capstone project during twelfth grade. I watched students in my district complete this requirement by writing book reports or writing papers about what they wanted to be when they grow up. That’s the kind of project one would see in elementary school, not high school, and it in no way prepared students for the rigors of college, where research is essential to being successful.

These are just a couple of examples of how the weak alternatives available to the class of 2018 were a disservice to students and schools. Ohio needs graduates who are college and career ready, and it needs schools, teachers, and students to be held accountable for learning. But graduation requirements should also acknowledge student growth. That’s why I’d like to make the following proposal for how to change Ohio’s graduation requirements.

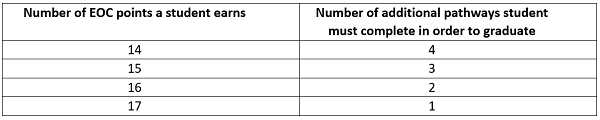

Under my proposal, students would still be required to take end-of-course (EOC) exams and accumulate points based on their scores. Instead of having to earn eighteen total points on EOC tests to graduate, students would only need to earn fourteen points on exams. Students who earn fourteen or more points—but less than eighteen—would be required to complete additional pathways to demonstrate their readiness.

The number of pathways that a student would need to complete would depend on how many EOC points they accumulated. Take a look:

These pathways would be an improved version of the 2018 alternative requirements, and would include:

As you can see, many of the problems with the 2018 alternative requirements would be resolved under the new proposal. Removing attendance as an option, for example, ensures that showing up is an expectation for all students and prevents adults from gaming the system. By increasing the number of hours students must work in a job or community service project, limiting the project to one site, and requiring a favorable evaluation from a supervisor, students will be held accountable for their performance, learn what employers want, and demonstrate perseverance.

As far as EOC exam performance, as is the case under current law, students would still be required to earn at least four points in English, four in math, and six points in science and social studies. At least one of the additional pathways a student completes must be an out-of-school experience. In addition, this pathway places an emphasis on growth requiring all students to retake each year any test on which they score less than proficient until they either become proficient or graduate. It has teeth, too, as students are not permitted to graduate using the EOC pathway if they have a final score of “limited” on any assessment. If students improve their EOC scores and earn more points, they can decrease the number of pathways they must complete.

There are a few reasons this proposal is better than those currently being advocated for by the State Board of Education. First, it gets incentives right. Maintaining testing requirements for graduation ensures that students will take tests seriously and that report card measures like the Performance Index will accurately report achievement, not student effort. Removing easily gameable options like attendance also prevents adults who, though they may have good intentions, have low expectations for students. And maintaining EOC testing ensures that everyone—students, teachers, and schools—are accountable for student learning.

Second, this proposal focuses on growth instead of just compliance and achievement. By having students retake tests until they earn a proficient score, the state is communicating the importance and value of perseverance, as well as holding schools accountable for giving students intensive remediation and intervention. Importantly, a student who improves and earns additional EOC-exam points will need to complete fewer pathways to reach the required eighteen points.

As one can see, this is not a substitute for testing. It is all about achievement, growth, and accountability for students, staff, and districts. This is a compromise that all groups can get behind. It is what Ohioans expect but rarely get from Columbus and Washington—the ability to find common ground. As a teacher who has dedicated my life to helping the next generation, I implore the legislature to adopt a common-sense middle ground like this that maintains a focus on academic achievement but gives students additional, meaningful opportunities to demonstrate college and career readiness. Our young people deserve it.

Mr. Soper is an Ohio teacher. This blog reflects the views of the author and may not reflect the views of the Canton City School District, Canton Professional Educators’ Association, or the Ohio Education Association.

In our recent writings at the Ohio Gadfly, we’ve expressed dismay—sometimes outrage—at the education goings-on in the Buckeye State. To be sure, there’s a lot to be concerned about: The State Board of Education has gone soft on graduation requirements, and policymakers are talking about dismantling transparent school ratings and replacing them with opaque “data dashboards” that display a blizzard of statistics only technocrats can comprehend. On top of this is the reality—reinforced once again by the 2017–18 state exam data—that many thousands of Ohio’s children remain academically off track.

But amid this glum picture, there are terrific accomplishments and initiatives well worth highlighting. Consider just four that recently caught my attention (and feel free to send along others).

Ohio’s Straight-A schools

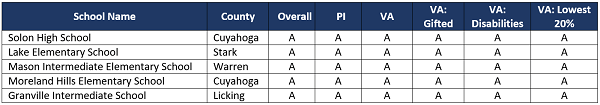

Let’s first give credit where credit is due—to the cream of the crop in terms of earning top marks on school report cards. The table below shows five schools that received A’s on the overall rating—a composite of Ohio’s various components—and on five critical measures of achievement and growth on state assessments: the performance index (PI), overall value added (VA), and three subgroup value-added indicators that are based on growth results for gifted students, students with disabilities, and students in the lowest 20 percent in statewide achievement. (Click here for a map showing the schools’ locations.) On average, pupils in these schools are achieving at very high levels on state tests, as indicated by A’s on the performance index. In addition, students across all parts of the achievement spectrum—low and high achievers alike—are making gains, as evidenced by the A’s on the value-added growth measures. Clearly, earning A’s in all these areas is challenging and especially so for high-poverty schools that typically score lower on the PI. But hopefully in the coming years, we’ll begin to see more schools break into this exclusive club. As for the fantastic five below: Job well done—and hope to see you again next year.

Table 1: Ohio’s Straight A schools based on 2017–18 report card ratings

Cleveland’s school quality guides

Led by Governor Kasich and Cleveland’s civic and educational leaders, the Cleveland Plan has been one of the state’s highest-profile school reform efforts. Among the plan’s central initiatives was the creation of a nonprofit group, the Cleveland Transformation Alliance (CTA), which among a few other things is tasked with “communicat[ing] to parents about quality school choices.” For several years running, the CTA has published a superb School Quality Guide that aims to provide independent information that can assist Cleveland families in their search for a quality public school. With 170 public schools, both district and charter, there is a wide range of options in Cleveland, though not all have consistently delivered an excellent education. That is why CTA’s user-friendly guide (and website too), including the most recent one released just this week, are so indispensable. This year’s version contains one-page profiles of every public school that contain key academic results—including their performance-index and value-added ratings—and importantly for Cleveland parents, information about how each school ranks in comparison to other city schools on these metrics. If they’re not already publishing parent-friendly materials like this, city leaders in other locales (ahem, Columbus and Cincinnati) should consider using the CTA’s work as a starting point. And the next big step: creating a common enrollment system for all district and public charter schools in a given city.

An evidence-based clearinghouse

Following trends in medicine and management, one of the catchphrases in education is “evidence-based” practices. It’s specifically referred to in the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which requires districts to deploy evidence-based interventions if any of their schools are deemed low performing and in need of improvement. (Whether or how states will enforce this requirement is less certain, as Mark Dynarski of the Brookings Institution has written.) Whatever the case, evidence-based practices are on educators’ radars—and that’s a good thing, as research has often been ignored in K–12 education. While the U.S. Department of Education has long hosted the What Works Clearinghouse, which provides reviews on a slew of program evaluations, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) recently launched a new website intending to reach educators across Ohio. ODE’s webpage helpfully organizes studies into evidence tiers, based on the strength of the research design (from experimental to less rigorous methods), as well by type of intervention (e.g., curriculum or school climate), grade span, or content area. With any luck, ODE will continue to invest in and develop this online tool—there is, for example, only one study on “human capital management.” Lastly, one suggestion from the cheap seats: It would be great to be able to search for rigorous studies from Ohio. That way, local educators could more easily locate and learn from nearby schools or service providers—maybe even one down the street—that implemented a program that worked.

A growing network of STEM schools

With much fanfare, LeBron James’s new school in Akron opened its doors this fall. One of the lesser-known aspects of the school is that it’s part of Ohio’s growing network of STEM schools (science, technology, engineering, and math). As a relatively new innovation—the Ohio STEM Learning Network (OSLN) was formed in 2008 with the support of Battelle and the Ohio Business Roundtable—many Ohioans may not be familiar with the model. A recent OSLN publication provides a useful look at the growth in STEM schools across the state, which now include fifty-five schools, serving more than 25,000 students. As the report states, such schools must have open admissions; create partnerships with local businesses, colleges, and districts; use teaching methods “based on real-world problems”; and spread innovative practices through the network. Schools must apply to a STEM committee established by state law to receive such a designation. The network also spans “sectors”: It includes district-operated schools (like LeBron’s I Promise school), public charter schools (such as Dayton Early College Academy), a dozen or so private schools, and seven independently governed STEM schools. While a hard-nosed STEM curriculum may not be suited for all, Ohio needs to foster talent in the STEM fields to meet demands in technical careers. Kudos to these schools that are opening STEM opportunities to more young people.

***

As Jim Collins writes in his classic book, Good to Great, we must acknowledge and confront head-on the difficulties of the present. But at the same time, we need always to maintain an unwavering optimism about the future. In the case of education in Ohio, there’s much hard work in the here and now to safeguard rigorous expectations for all students—and ensure that every child has opportunities to succeed in school and in life. At the same time, successful and innovative schools, along with important initiatives that empower families and educators, give us hope for the future of education.

In August, the Ohio Department (ODE) of Education and the State Board of Education (SBOE) released their five-year strategic plan for education. It included ten strategies aimed at helping the state meet a questionable goal that doesn’t ask much of students or schools. One of these strategies called for identifying “robust and diverse ways to measure performance.” Take a look:

Ohio needs to address challenges related to a reliance on standardized assessments in academic content areas, especially in high-stakes situations. Students should have multiple ways to demonstrate what they know and are able to do. The State Board of Education recognizes this point and is examining the use of alternative tools as validated, reliable methods to assess knowledge. Such tools might include student portfolios, capstone projects, presentations, or performance-based assessments.

Less than a month later, state board members are already debating a draft proposal for a new set of graduation requirements that includes alternatives to assessments. Students would be able to choose how to demonstrate their competency in English, math, and other subjects from a laundry list of options. One of these options is a non-test-reliant pathway called a Culminating Student Experience (CSE).

The draft proposal offers a relatively detailed look at what a CSE could be, though little guidance on what it must be. It is described as a “project or set of activities and experiences” that can be embedded into existing school programming and could include in-school and out-of-school activities. It’s up to students to choose which activities they’re going to complete. Provided examples of such activities include a research or portfolio project, a community service project or experience, a work-based learning experience, or the completion of a career-technical program or an in-demand credential. Despite these examples, the proposal notes that students and their advisors are free to choose “activities and experiences that are aligned to the particular student’s aspirations, interests, and future plans.”

But here’s the real kicker: Depending on the activities they choose, students could use a CSE to meet all of the state’s graduation requirements. For example, to fulfill the English requirement using a CSE, students must complete a writing demonstration and achieve a rating of “satisfactory” on a rubric. For math, it’s a mathematical competency/data analysis demonstration and another satisfactory rating on another rubric. For both the “well-rounded content” requirement (which includes subjects like social studies and science), and the leadership/reasoning and social-emotional-skills requirements, it’s nothing more than presenting a summary of the CSE to a review panel. Students who can complete each of these demonstrations satisfactorily (it’s unclear what that means because the rubrics don’t exist yet) will earn a diploma.

To be clear, the draft proposal is not a formal recommendation from SBOE and ODE. The document clearly states that it was created “for discussion purposes only,” and State Superintendent Paolo DeMaria told the board that details would still need to be worked out if the concept was approved. But any proposal deemed worthy of discussion by a group that’s been so highly critical of current graduation requirements deserves a close look. And these “details” are not small, trivial things that can be waved away as implementation concerns. In fact, stakeholders and advocates should be extremely concerned about this proposal moving forward.

For starters, the proposal does not require certain experiences or activities to be part of a CSE. Instead, in an attempt to give students the freedom to align their CSE with their aspirations, interests, and future plans, it offers blanket approval for pretty much anything: “The Culminating Student Experience could include any meaningful collection of activities and experiences” (emphasis mine). As long as a student can write about what they did, do some math related to it, and present it to a review panel, then they’re free to use it as a pathway to a diploma.

Wanting to give students the freedom to align school to their interests and goals is a laudable idea. A recent survey indicated that only half of students think that what they learn in school is relevant to the real world, and some students struggle to stay engaged in school when they don’t see it as pertinent to their lives. Schools should absolutely be working toward connecting academics to real life. But the state should not be granting diplomas based on an open-ended list of student-selected activities that it cannot prove will develop or accurately measure academic knowledge and skills.

Consider one of the few activities the proposal identifies as a possible CSE: a major community service project/experience, such as a significant leadership role in a student organization. Although such activities are undoubtedly meaningful for students, they aren’t reflective of academic mastery. Johnny may have learned a ton from his time leading a student organization, but writing an essay about his experience to meet ELA graduation requirements overlooks almost every single one of the state’s reading standards. Johnny will graduate without proving that he can make logical inferences, determine central themes, assess how a point of view shapes content and style, or compare and contrast two texts—skills that are absolutely vital in college and a vast majority of workplaces, not to mention typical adult experiences, like deciding which presidential candidate to vote for or reading a lease agreement.

There is no way for the state to ensure that every CSE activity a student chooses is high quality. Instead, policymakers will rely on teachers and administrators to do it—a decision that will heap even more onto the already full plates of folks on the ground. The sheer amount of time and manpower it will take to not only monitor student selections but also grade and evaluate all of the associated demonstrations in addition to daily classes boggles the mind. Professional development and training will cost the state millions.

But that’s not all. In a previous piece, I pointed out the drawbacks of using GPAs as a graduation requirement (which the proposal also advocates for). Many of the same issues with GPAs exist for CSEs: an enormous amount of pressure on the teachers tasked with grading; the potential of score inflation and gaming; and wildly different expectations between schools and districts, and even for different groups of students that make comparison and validity all but impossible. That last point—the impossibility of comparing between districts, schools, and subgroups of students—should terrify equity advocates. The state has a responsibility to ensure that all children are learning, and to do everything in its power to close the achievement gap. That’s not possible if we can’t compare the graduation rates of poor, minority, and underserved children to the results of their more affluent or white peers.

And then there are concerns about reliability. The proposal suggests that students could complete a portfolio project either as part of a CSE or to complete their well-rounded-content requirements. The state of Vermont implemented a similar portfolio assessment program back in the early 1990s. Research into Vermont’s work showed that “rater reliability,” or the extent of agreement between raters about the quality of a student’s work, was low, on average, in both math and writing. The authors of the report note that when ratings are unreliable, “scores tend to spread out more than they would with reliable scoring.” This results in too many students obtaining scores on the extreme ends of the spectrum, and too few students obtaining scores near the middle. In Vermont’s portfolio system, the resulting bias was “substantial enough to undermine reporting of statewide proportions of students reaching each score point.”

Other assessment alternatives proposed by the plan have similarly questionable evidence bases. In a review of the literature on high school capstone courses, authors found that, “while the idea of such courses has been around since the 1990s, such courses have not been widely implemented and virtually no research exists on their effectiveness.” Work-based-learning experiences are promising, but still in their infancy: The ODE-developed framework for how schools should issue high school credit to students completing work-based learning didn’t go into effect until this year. The state is still working on how to reliably measure work-based-learning participation and evaluate performance.

The upshot of all this is clear: The state board and ODE promised to examine alternatives to assessments to see if they were valid and reliable. But there was no examination. In fact, given the speed with which this new draft proposal came out, it seems that their minds were already made up. That stands in stark contrast to other states that are also considering test alternatives but are doing so carefully, via small-scale pilots and extended timelines, and with the worrisome concerns of equity and reliability front and center.

It should greatly concern parents, educators, and the general public that the alternatives proposed in the draft plan not only lack solid evidence of validity and reliability, but are also burdensome, subject to gaming, of questionable rigor, and completely devoid of the state’s reading standards. This is not to say that all alternative assessments are bad; they may very well be excellent assessment tools at the local level, and they could become an important complement to (though not a replacement of) state tests. Nor is the point to champion standardized tests as the be all and end all. Standardized tests don’t tell us everything we need to know about student potential, achievement, or ability. But they are objective, valid, reliable, comparable, and rigorous tools that gauge what students know and are able to do—something that can’t be said for the alternatives offered by the draft proposal.

Editor’s Note: As Ohioans prepare to elect a new governor this November, and as state leaders look to build upon past education successes, we at the Fordham Institute are developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is the fourth in our series, under the umbrella of empowering Ohio’s families. You can access all of the entries in the series to date here.

Proposal: Authorize the ODE to develop and oversee a statewide course-access program. To implement the program, a funding mechanism should be created to pay online course providers and develop accountability tools that verify student learning.

Background: Traditionally, families and students have chosen a single school that delivers the entire educational experience. Although this “bundled” approach works well for many, the courses offered at any one school may not match the needs of every student in attendance, particularly in the upper grades. For instance, national data show that only half of U.S. schools offer calculus and just three in five offer physics. Closer to home, 139 Ohio districts—primarily rural—report that none of their recent graduates participated in Advanced Placement (AP) or International Baccalaureate (IB) courses. Hundreds, if not thousands, of students attending these schools could have benefitted from such advanced coursework but may have missed such opportunities due to schools’ resource (or other) constraints. To overcome these barriers, several states, including Florida, Texas, and Virginia, have unlocked course-level opportunities via technology. This approach permits students to attend their local schools but also incorporate state-approved online courses into their schedules. These may include advanced courses such as AP or IB or electives such as foreign languages, accounting, and information systems.

Proposal rationale: Families and students shouldn’t have to sit idly by, or switch schools altogether, when courses aren’t offered by their local schools. By developing an online course-access program, Ohio would allow students to remain in their local schools while better tailoring their schedules to their academic abilities and interests. At the same time, state oversight would ensure course rigor and proper tracking of pupil performance.

Cost: The state would need to allocate sufficient funds (perhaps $5 million per year) to develop a course catalog and maintain oversight of the available courses. To compensate course providers, the state should subtract funds from districts’ per-pupil state aid in proportion to the number of courses taken by a student. For instance, assuming a student takes two online courses and six “regular” courses at her district, the district would receive 75 percent of the state per-pupil allocation for that student.

Resources: For discussion of policy design and examples from other states, see Michael Brickman’s report Expanding the Education Universe: A Fifty-State Strategy for Course Choice, published by the Fordham Institute in 2014 and the Foundation for Excellence in Education’s “Course Access: Policy Toolkit” (2018). For national data on course-taking patterns, see the U.S. Department of Education report STEM Course Taking (2018). Ohio data on AP/IB course taking is available at the ODE web page “Ohio Report Cards: Download Data” (see also figure 5).

Editor’s Note: As Ohioans prepare to elect a new governor this November, and as state leaders look to build upon past education successes, we at the Fordham Institute are developing a set of policy proposals that we believe can lead to increased achievement and greater opportunities for Ohio students. This is the fourth in our series, under the umbrella of maintaining high expectations for all students. You can access all of the entries in the series to date here.

Proposal: Starting as students enter middle school, Ohio should provide families with clear information about whether their children are on a solid pathway for success in college.

Background: As objective gauges of student achievement, statewide exams have several important purposes, including their use in school accountability systems. But perhaps the most important role of state exams is to offer information to Ohio parents about the academic progress of their own children, thus serving as an important “external audit” that supplements the grades they receive from teachers. To this end, the Ohio Department of Education produces family score reports based on state exams, akin to those that families receive after children take college entrance exams. The state’s score reports already provide some valuable information to parents, most notably, whether students reach proficient. While Ohio has raised its proficiency standards in recent years, data suggest that a substantial number of proficient students—perhaps up to one in four—are likely to struggle should they choose to pursue a college education. In 2016-17, roughly 60 percent of Ohio students reached proficient on various state exams. However, ACT data from the class of 2017 indicate that just 46 percent of Ohio graduates taking this exam reached college-ready benchmarks in at least three of its four subject areas; even fewer (33 percent) met its readiness targets in all four. Widely seen as the nation’s gold standard for reporting achievement, data from NAEP reveal that just two in five of Ohio’s fourth and eighth graders reach its rigorous proficiency bar. An on- or off-track for college designation should not be presented as certain or fixed (and changes over time could be displayed too). But surveys find that parents tend to overestimate the academic skills of their children—due in part to the rise of “grade inflation” in schools and modest proficiency standards—and a projection of college readiness would offer a realistic appraisal of where children stand on the path to post-secondary education.

Proposal rationale: Ohio, like most states, hasn’t fully aligned its proficiency standards with college-ready benchmarks. The result: parents do not receive clear signals about whether their children are on-track for college often until it’s too late. Although college may not be the optimal path for all young people, it’s an aspiration that many parents have for their children—and most adolescents hold for themselves. Through a partnership with the data-analytics company, SAS, Ohio already provides data to educators that forecast students’ ACT or SAT scores based on state exams results. This information should be provided to families as well. Providing projections about college prospects could inspire them to engage more actively in the educational success of their children, encourage them to seek academic help, if warranted, and support informed decisions about high school options and beyond.

Cost: Minimal fiscal impact on the state budget. The Ohio Department of Education would likely incur nominal administrative expenses to update its family score reports.

Resources: For more on states’ proficiency standards, including analyses showing that Ohio has a relatively low proficiency bar, see Daniel Hamlin and Paul Peterson’s article in Education Next titled “Rigor of State Proficiency Standards, 2017” (2018); for Ohio’s NAEP and state proficiency rates, see the Fordham Institute web page, “Ohio By the Numbers”; and for ACT data for Ohio’s class of 2017, see ACT, “The Condition of College & Career Readiness 2017: Ohio Key Findings.” Survey data on parents’ views of their kids’ achievement and college aspirations can be found in Learning Heroes’ 2017 report “Parents 2017: Unleashing Their Power & Potential” and Jon Marcus discusses grade inflation in an article titled “Why Suburban Schools Are Inflating Kids' Grades,” The Atlantic (2017). For information about family score reports, see Ohio Department of Education, “Ohio’s State Tests, 2017–18” and for a note about how educators can access predictive analytics on ACT/SAT scores, see ibid., “Updated reports available on EVAAS value-added site.”

Although ardent school choice supporters often argue that having options is an end in itself, the more pragmatic among us recognize that important real-life factors must be considered when describing the health of an area’s school choice landscape. Improvements in information dissemination and simplification of enrollment processes are making a difference in many cities, but a continuing obstacle is transportation. Even the best possible school option might as well not exist if a family cannot reach it. New research from the Urban Institute tries to identify the calculus that families must make in their efforts to secure the best possible fit.

Researchers Patrick Denice and Betheny Gross use data from Denver Public Schools, a portfolio system that includes traditional district schools, independent but district-run innovation schools, and charter schools. All Denver students are guaranteed a spot in a specific school or cluster of schools, but are free to apply to schools of any type for which they are eligible and they do so via a centralized application. School assignments are generally determined by lottery. As befits a system with this much choice and a simplified single application system, more than 80 percent of Denver students in typical transition years (e.g., entering kindergarten or moving from fifth to sixth grade) submit school choice applications. Noting that most students applying to high school do not apply to the school closest to where they live—the first choice is typically the fourth-closest school—Denice and Gross focus on students entering ninth grade to examine the trade-offs made in pursuit of this important choice.

Their study examined all rising ninth graders at the start of the 2014–15 school year who submitted a school choice application—a total of 3,100 students. The researchers used district data to determine all of the possible schools available to those students for that year (by application and by guarantee), used Google Maps to calculate the distance and time it would take students to travel via transit or car from their homes to all options, and then compared the results to their first choice school. It is important to note that this analysis was not based on the schools that students actually ended up attending, but only those they requested first on their list (students can request up to five ranked options), and that schools “bypassed” refers to any school that is closer than the first choice in any direction of travel. Half of the students’ first choice schools required less than a ten-minute drive each way, but the range was large—from almost zero to more than fifty minutes. The city’s median black student sought schools the furthest from home at nearly fifteen minutes one way. Overall, the median student bypassed four nearer available schools in selecting their first choice school; the median black student bypassed seven.

Wanting to know what motivated students to bypass certain schools and to subject themselves to longer travel time to attend their first choice school, Denice and Gross focus on a group of students they call “super travelers.” Super travelers fall into the top quartile of the sample in terms of travel time or the number of available schools they bypassed if they were assigned to their first choice. A surprisingly large 31 percent of students (nearly 1,000 total) fit the criteria. Super travelers would spend, on average, 21 minutes to reach their final choice school. While that may not sound like much on paper, keep in mind that travel time is one way and does not here include real world traffic considerations such as congestion, construction, or weather. Additionally, it does not consider parents transporting multiple children to multiple schools and the requirements of parents’ employment or the cost of wear-and-tear on vehicles. More importantly to the foregoing, the number of closer available schools to the average super traveler was a whopping 16.8 due to co-location of smaller “schools” within several given high school buildings.

Denver’s notoriously tricky geography, with a number of historically isolated neighborhoods, did not appear to influence super travelers’ choices, with a reasonably even distribution of super travelers originating from all of the city’s defined sectors. As a result, the researchers focused on what the students would be traveling for—the differences between far-away first-choice schools and those that are nearer but bypassed. They began by comparing characteristics of the schools nearest to super travelers’ homes to their first choice schools. They found that students favored schools with higher academic quality (as measured by ACT scores and graduation rates), lower discipline rates, and richer academic and extracurricular offerings (as measured by availability of Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate courses, Calculus, dual-language and immersion options, sports offerings, project-based learning, and music, drama, and visual arts). Families opting for quality should be music to the ears of school choice supporters. But travel distance remains an issue. Studies show that long commutes are associated with large costs in terms of time, money, lost opportunities, neighborhood social ties, and potentially traveling to or through unsafe areas. Not to mention unreliable transportation which could lead to dropping out.

But what about all the schools bypassed by super travelers? Unfortunately, the data indicated that only 22 percent of Denver’s super travelers could find another comparable choice nearer their homes, and even those would lessen their commute time by only a few minutes. Again, there is no indication here which additional schools students requested other than their top choice, nor which schools they ultimately attended. This limits the conclusions that can be made but does provide important descriptive information about what students and families are willing to do to attend the school that they want. Looking at the data, Denice and Gross noted that other nearer choices were available if certain parts of the quality criteria were relaxed, but the onus should not be on parents to compromise. It should be on school systems offering choice to think more holistically about their offerings, as it seems most families do.

Diversifying and improving the “package” of academics, culture, and extracurriculars and focusing on those school characteristics most in demand would go a long way to helping more students find the best fit. And transportation options—whether it be a school or city bus—that address the reality of families’ travel requirements wouldn’t hurt either.

SOURCE: Patrick Denice and Betheny Gross, “Going the Distance: Understand the Benefits of a Long Commute to School,” Urban Institute (October 2018).