Ohio’s news outlets have covered the debate over graduation requirements as if it were a burning problem that policymakers need to urgently “fix.” For instance, the local NPR affiliate headlined an article, “Ohio education panel still crafting long-term fix on graduation standards.” The Dayton Daily News ran a piece titled, “State school board backs long-term graduation changes, weighs emergency fix.”

Such headlines are likely inspired by public officials who have raised alarms over the past two years that Ohio’s new graduation standards would withhold diplomas from too many students. In fact, one former State Board of Education member predicted that graduation rates would fall sharply to 60 percent for the class of 2018, the first cohort subject to the state’s updated requirements that include exam-based and career-technical pathways. Based on these concerns, state lawmakers approved softball alternatives that this cohort could meet to receive high school diplomas. Various policymakers have expressed interest in extending less demanding options to future graduating classes.

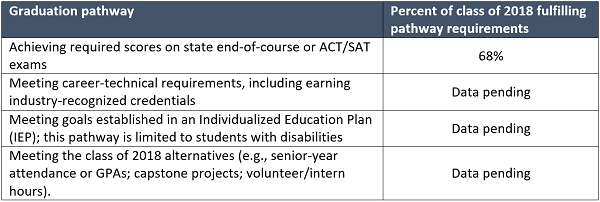

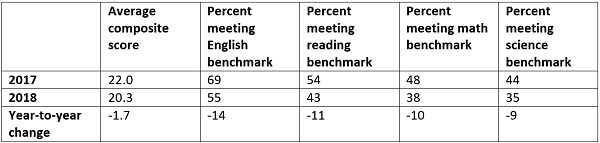

Now that much of the class of 2018 has moved onto bigger and better things, it’s a good time to step back and see how these students fared in terms of meeting graduation standards. Should there be continuing concern over the possibility of dramatically lower rates? At the October state board meeting, the Ohio Department of Education released the following data:

The first thing to know about these data is that this calculation includes the entire class of 2018—not just students enrolled in their senior year—and thus includes students who have dropped out. This is important because we can compare, roughly, the graduation rate for the class of 2018 to previous years, which include dropouts, to see if rates would’ve plummeted to unprecedented levels had there been no alternatives.

Now to the data: We observe that 68 percent of the class of 2018 met the exam-based requirements. Right off the bat we can rule out concerns that graduation rates would’ve fallen to 60 percent. ODE does not yet have data on students meeting the career-technical requirements—a rigorous pathway that requires young people to earn industry credentials. In recent years, 4 percent of Ohio’s graduates earned such credentials, but that number may rise now that it’s included as a pathway. Let’s add a few percentage points to the 68 percent rate—perhaps 4 to 7—to account for these graduates. We also see that some special-education students may earn diplomas via their IEP goals. While this number may fall under new federal guidelines, roughly 5 percent of the class of 2017 earned diplomas through this pathway. [1] Using these three existing means for earning a diploma, it’s likely Ohio would have registered a graduation rate of about 77 to 80 percent. That’s without any alternatives pathways. As for the alternatives, odds are that at least a small percentage of these students would have earned a diploma through the original pathways without the additional options being available.

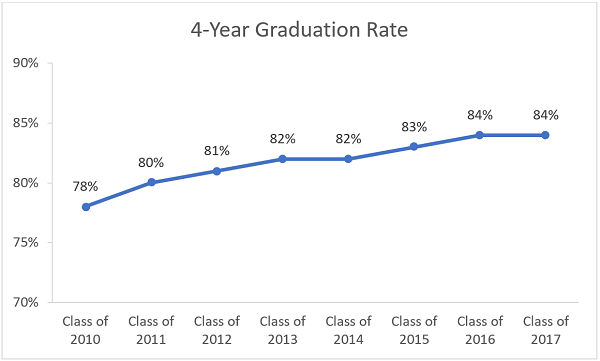

A graduation rate in this range would be somewhat lower than in the most recent years. However, rates in the mid- to high-70s are not exceptionally low, as the chart below indicates. Bear in mind that these rates reflect students who graduated under the eighth-grade level Ohio Graduation Tests (OGTs), while current students have to meet more demanding requirements. Thanks to the hard work of the class of 2018 and Ohio’s educators, this was the “apocalypse”—as one superintendent predicted—that never came to pass.

Figure 1: Ohio graduation rates, classes of 2010 through 2017

The more important question—then, just as now—is how to better support the 15 to 25 percent of students who are on the shakiest paths to post-secondary success as adults. In this regard, Ohio does face a problem that demands solutions. The answer, however, isn’t to find ways to shamelessly manufacture, diploma-mill-style, credentials backed by no objective demonstration of the academic or technical competencies needed for college, career, and military service. Softened standards permit young people to enter the “real world” ill-equipped to meet the more rugged demands of colleges and employers. They also discourage young men and women from accumulating valuable skills and abilities. This is the opportunity cost of less rigorous pathways. How many students in the class of 2018 stopped working hard to meet academic or technical goals when the easier routes were introduced?

The answer, rather, is to recommit to efforts that strengthen the readiness of young people for life after high school. This means focusing on teaching math, English, science, and social studies—the four core subjects critical to success in life—so that more students can breeze through their end-of-course exams. It also means opening more quality career-and-technical opportunities, including access to industry-credentialing programs and business-based apprenticeships. It means encouraging students, as they enter high school, to set ambitious goals—and cheering them on as they work hard to meet them—and it could mean, at times, delivering tough news about the work ahead. It might also require ramping up fifth-year high school programs, or improving adult education that supports GED acquisition. Contrary to what some seem to believe, life isn’t over if you don’t complete a high school education in four years. Of course, it also means starting early by teaching reading properly in elementary schools and ensuring that youngsters gain a rich knowledge base, so that they’re well prepared for high-school-level work.

Let’s stick a fork in the argument that Ohio’s graduation rate would fall through the floor under the new requirements. The data just don’t support that story. Instead, policymakers would better serve Ohio’s young men and women by focusing on ways to improve academic achievement and technical-skills acquisition for all. Former State Board president Tom Gunlock got to the heart of the matter when he wrote on these pages:

Yes, it [helping all students meet high graduation standards] will be hard work. Yes, it will push all of us outside our comfort zones. We know that the conditions aren’t always ideal for change to occur. We’ll find strength in working together and supporting each other, and knowing that the work we do will create hope—hope for our students, hope for our communities, and hope for the future of our state. Let’s commit ourselves once again—educators, state government, communities, and partners of all varieties—to do what we know can be done. Our children and future generations will thank us.

Well said.

[1] Moving forward, it’s unclear how Ohio will report students earning diplomas through their IEP. For the purposes of comparing class of 2018 data to prior years, this analysis assumes that they are counted in the 2018 graduation rate, since this was done in prior years.