The promise of mastery grading (continued)

Pros and cons of mastery-based education

Pros and cons of mastery-based education

In a previous post, I explained competency-based or “mastery” grading: a restructuring of the common grade system that compresses everything from course tests, homework, and class participation into a system that assesses students based entirely on whether or not they’ve mastered specific skills and concepts. (For a look at how mastery grading works in practice, check out how schools like Columbus’s Metro Early College School and Cleveland’s MC²STEM high school, and even suburban districts like Pickerington, make it work). In this piece, I’ll discuss some additional benefits and drawbacks of mastery grading.

Mastery grading is innovative in that students only move on to more complex concepts and skills once they mastered simpler ones. As a result, the failure to master on the first attempt isn’t “failure.” It’s a chance for students to receive additional instruction and support targeted at specific weak spots, work hard, master key concepts, and move on with a firm foundation in place.

For teachers, the possibility of meaningful achievement data that is disaggregated by child and skill and directly drives instruction should be drool-worthy. Imagine knowing at the beginning of the year—before ever giving a diagnostic assessment—what your new students have fully, partially, and not-yet mastered.

To be clear, implementing mastery grading effectively will take a shift in mindsets, habits, and practice, and it will increase the administrative burden at first. Teachers will have to be true masters of their content. They will also be called upon to plan even further in advance: If students are meant to move on once they master a concept, they will need a place to move on to—including new concepts, ways to practice, and assessments. The students who don’t master concepts on the first try will need remediation in various different forms. Yes, differentiation is hard, but mastery grading systems—if implemented effectively— offer a genuine chance to get it right. Schools adopting mastery grading could mitigate the time burden by providing teachers with additional planning time. Schools could also designate time for teachers of the same subject to share resources and ideas. Teachers can leverage online resource-sharing hubs, including sites that boast lessons written by effective teachers. There are applications that make tracking mastery data easy, allowing teachers to focus on planning instead of tracking. The rise of blended learning and adaptive models makes effective, personalized remediation real without asking teachers to build a system from scratch on their own. Plus, once systems and materials are created, they need only be improved—meaning that the burden decreases with time.

One of the most vocal arguments against mastery grading is that it sets kids up for failure. Those who make this argument believe that it’s wrong to take away the “help” we give to students who struggle: points for showing up, points for being on time, points for homework completion, points for participation, points for extra credit. But grades were designed to reflect academic achievement. When we report performance influenced by factors like attendance, behavior, or assignment completion, we struggle to stand behind grades as an accurate assessment of what our students have truly achieved. It’s not that attendance and effort don’t matter—it’s that they should be tracked separately from achievement. Otherwise, high-performing students who struggle with completing homework are labeled as academically struggling, and academically struggling students who are diligent in homework and attendance have no idea that they aren’t progressing. Teachers should always have full authority to track and report any metric they deem necessary, including homework or behavior. But achievement is achievement—and should only be measured by content mastery.

No one wants to tell the hardworking, well-behaved kid that he needs remediation. But this isn’t about what adults want, or what’s easiest for them. It’s about what kids need. When adults say that mastery grading will set kids up for failure, what they’re really saying is that they’d much rather let kids graduate with a diploma that’s a lie and let them deal with the fallout rather than take responsibility for a system that fails millions of kids every year simply by passing them along. We see this already in far too many cities in Ohio and across the country.

Do I empathize with the high school teacher who bristles at mastery grading ninth graders who read at a fourth-grade level? Yes, particularly because I was one. Mastery grading isn’t a silver bullet. But that doesn’t mean we should keep lying to students about their performance. Students and their families deserve to know where they stand. The remediation and individual attention that mastery grading engenders is exactly the kind of attention that struggling students, high-performing students, and every student in between needs. It’s the kind of honest, kid-focused approach that all students deserve. Governor Kasich’s proposed pilot program is a smart way to test if this approach can work at scale—and to determine how it works in practice in various contexts.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The original version of this commentary was published on EdReform Now’s blog on April 8. The post contrasted innocent misunderstandings (using Allstate’s elderly-woman-misunderstands-social-media esurance ad) to the more serious act of purposely leading people to misunderstandings. The post simply and succinctly clears the air about how school funding – especially for charter schools – actually works in Ohio.

When “policy experts” purposely mislead the public into misunderstandings about education and school funding, it isn’t a humorous misunderstanding. It’s appalling.

For example, charter school detractors promote the idea that charter schools exist to privatize education and make profits for greedy investors:

“[Mayor Emanuel] took money from these schools . . . and gave it to elite private schools founded by his big campaign contributors. I would stop privatizing our public schools.“

- Jesus “Chuy” Garcia, Chicago Mayor election video

Actually, public charter schools are part of the public education system. They are approved and monitored by public entities. Nationally, nearly 90 percent are run by a non-profit organization (23% in Ohio). These non-profits are very much like other publicly-funded programs that serve children, such as Head Start centers.

Most egregious, however, is when detractors pit families against families with claims about unfair funding:

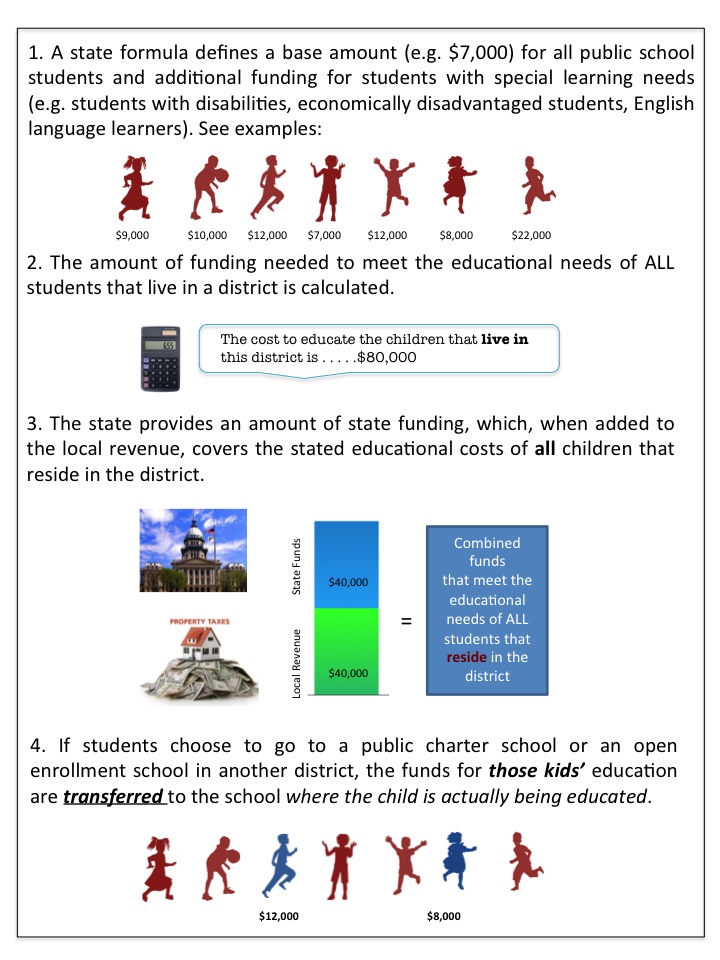

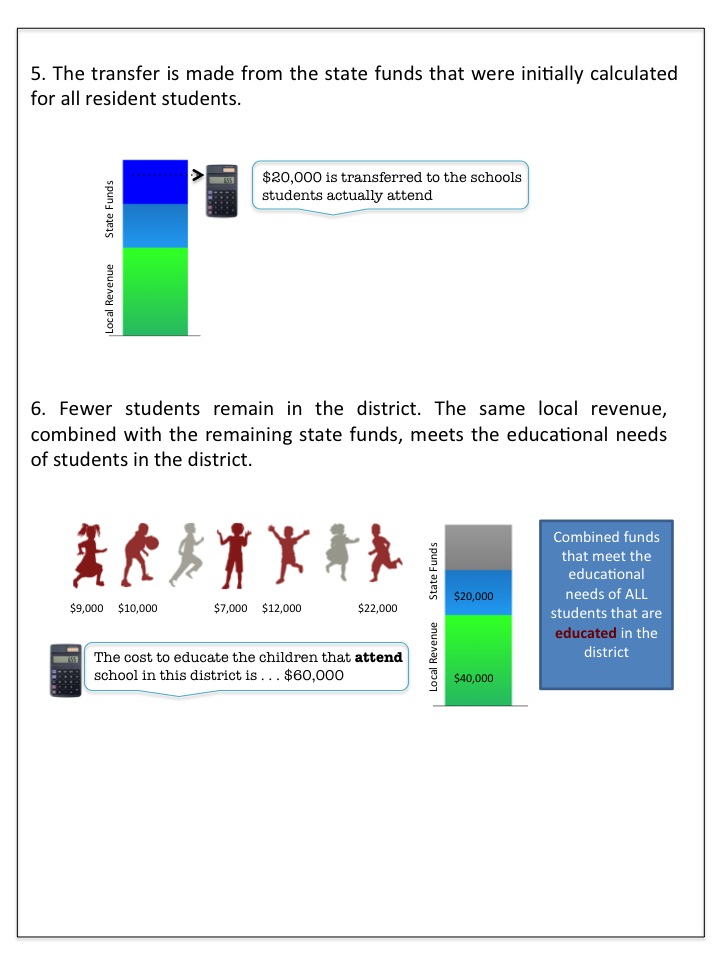

But these arguments don’t hold water because the funding associated with a particular student will follow him or her if he or she chooses to transfer from a traditional public school to a public charter school. In Ohio, this “pass-through” or transfer happens at the district level. That means that state funds provided to a district to educate a child will transfer to the school the child actually attends.

Here’s how it works:

Conclusion: There is no loss in funding for district students. District students have the same amount of per-pupil funding before and after the transfer.

If anything, district students actually get $3,500 more in per-pupil funding than charter students because:

1) Public charter school students don’t get the full amount of categorical costs defined by the state’s funding formula (charter school students get only 25% of the targeted assistance funds they would get if they were a district student, and e-school students are excluded from most types of categorical aid), and

2) Districts get state funds beyond the per-pupil formula. These include property tax rollbacks, homestead exemptions, and transitional aid or “guarantee funds” – which provide districts with funding for students they no longer serve. For example, Grandview Heights, a wealthy suburb of Columbus, gets $8,000 in extra state funds through transitional aid (Ohio District Funding reports).

How funds are transferred for charter school students is no different from how funds are transferred to the 80% of Ohio districts that allow students to transfer into their district through open enrollment or when parents decide to move to another district because they want better schools for their children.

But the difference – and benefit – with charters and open enrollment is that:

People who hold public positions of professional trust – such as school treasurers and superintendents, school board members, elected officials – have an ethical responsibility not to mislead the public. Yet, too often, the media – perhaps because conflict sells or perhaps because they don’t understand the school funding process – provides a platform that perpetuates misinformation.

So the next time you hear the rhetoric about how charter schools “take district funds,” please remember – That’s Not How This Works! That’s Not How ANY of this Works!

Marianne Lombardo is a Policy Analyst with Democrats for Education Reform, see bio here.

A February study from the Center for Education Data and Research aims to determine if National Board Certified Teachers (NBCTs) are more effective than their non-certified counterparts. Established in 1987, National Board Certification is a voluntary professional credential designed for experienced teachers in twenty-five content areas. Certification is awarded through a rigorous portfolio assessment process consisting of four components: content knowledge; differentiation in instruction; teaching practice and classroom environment; and effective and reflective practices. These components are analyzed via teacher “artifacts,” including videos of classroom lessons, student work, and reflective essays. Across the U.S., more than 100,000 teachers (or roughly 3 percent of the teacher workforce) is National Board Certified.

This study examines data out of Washington State, which boasts the fourth-highest number of NBCTs in the country. Washington provides financial incentives for teachers earning board certification, including bonuses of up to a $5,000 for teachers working in high-need schools. The study finds that NBCTs produce additional student learning gains on state exams that correspond to about 1–2 additional weeks at the elementary level and in middle school reading. In middle school math, the results indicate a whopping five weeks of additional learning, compared to non-NBCTs with similar experience. In other words, NBCTs post strong “value-added” results. The researchers also find that teachers with higher scores on the national board assessment program are also more effective than those with lower grades: An increase of one standard deviation in teacher assessment scores corresponds to 3–5 weeks of student learning gains (though this varies across certification areas).

An interesting component of national board certification is the option for teachers to “bank” their scores—if a teacher fails to earn NBCT certification on their first attempt, they are permitted to keep their scores in areas where they did well and resubmit their work in areas where they performed poorly. When researchers took a closer look at teachers who don’t achieve certification after their first attempt, they found no evidence that initially unsuccessful NBCTs are more effective than non-NBCTs—except in the case of middle school math, where initially unsuccessful NBCTs are still more effective than those who never earn certification. Even more fascinatingly, they found that initially unsuccessful NBCTs are less effective than NBCTs who successfully earn certification on their first attempt. This leads the researchers to conclude that, although variations exist depending on the type of national board certification, a teacher’s first attempt at national board certification “contains more useful information about teacher effectiveness than subsequent attempts.” Nevertheless, the big takeaway here is that NBCTs are more effective overall than non-NBCTs.

SOURCE: James Cowan and Dan Goldhaber, “National Board Certification and Teacher Effectiveness: Evidence from Washington.” Center for Education Data & Research (February 2015).

The process of reforming charter school law in Ohio took another big step forward last week with the introduction of S.B. 148 in the Ohio Senate. Jointly sponsored by Senator Peggy Lehner (R-Kettering) and Senator Tom Sawyer (D-Akron), the bill is the result of workgroup sessions over the last nine months to craft the best legislation possible to improve charter school oversight and accountability.

The new Senate bill follows on the heels of House Bill 2, a strong charter school reform measure passed by the House last month. The Senate proposal maintains many of the critical provisions that the House bill included and adds some additional measures. Specifically, the Senate bill:

We published a full roundup of press coverage of the rollout in a special edition of Gadfly Bites on April 16. Important highlights can be found in the Columbus Dispatch, the Plain Dealer, and the Akron Beacon Journal.

While the coverage has been almost uniformly positive, we urge you to read the op-ed published in the Beacon Journal on Friday, April 17. We have appropriated its title for the title of this Ohio Gadfly Extra: “The oversight of charter schools Ohio desperately needs.” In it, ABJ editors declare, “The charter concept is here to stay, made plain by the success stories, even in Ohio.” And they opine that S.B. 148 is “a foundation for much improvement”.

Anyone who doubted until now that these reform efforts are the real deal has hopefully had their doubts laid to rest.

In a 2011 Education Next article called “The Middle School Mess,” Peter Meyer equated middle school with bungee jumping: a place of academic and social freefall that loses kids the way the Bermuda triangle loses ships. Experts have long cited concerns about drops in students’ achievement, interest in school, and self-confidence when they arrive in middle school. Teachers have discussed why teaching middle school is different—and arguably harder—than teaching other grades. There’s even a book called Middle School Stinks.

In an attempt to solve the middle school problem, many cities are transitioning to schools with wider grade spans. Instead of buildings for grades K–5, 6–8, and 9–12 (or any other combination that has a separate middle school), districts are housing students at levels ranging from kindergarten through eighth grade on one campus. To determine if a switch to K–8 grade span buildings is in the best interest of Ohio districts, I took a look at the research, benefits, and drawbacks surrounding the model.

Research

A 2009 study examined data from New York City to determine if student performance is affected by two measures: the grade spans of previously attended schools, and transitions between elementary and middle school buildings. New York City provided the perfect laboratory for such a study, since it houses a large number of elementary and middle schools with a wide variety of grade spans that are managed under the same educational policies. The study found that students attending K–8 schools earned significantly higher scores than students who attended schools with other grade configurations, including dedicated middle school buildings. Specifically, students who remained in K–8 schools from fourth through eighth grade demonstrated test score gains between third and eighth grade that were, on average, about 0.25 standard deviations higher than students on a traditional grade span path. Furthermore, students who moved out of a K–5 building and into a K–8 building showed significantly higher eighth-grade performance in both math and reading—meaning that even older students who start on a different grade span pathway stand to benefit from transferring to a K–8 building. Interestingly, the authors were careful to note that schools serving wider grade spans and producing significantly larger test score gains between third and eighth grade did not appear to serve more privileged or higher-achieving students.

There are other studies that demonstrate similar results: A 2014 study of Texas schools found that average pass rates in writing, science, and social studies were higher for students enrolled in K–8 schools than for students enrolled in traditional middle schools. The authors of a 2011 review found that the majority of studies indicated that students who did not transition to typical middle schools did significantly better on GPAs, standardized math and reading tests, and state test composite scores than students who attended middle schools. The authors of the review also noted that students in established K–8 schools had higher state math scores than students in new K–8 schools, suggesting that academic gains for K–8 schools may not occur right away. A 2010 study demonstrated that in the year when students moved to a standalone middle school, their academic achievement fell significantly in math and English relative to students who continued in a K–8 school. Yet another study found that middle school students were more likely to fail a class in eighth grade or have poor attendance than students in K–8 buildings. To be fair, there are also studies that seem to show no relationship between grade span configuration and academic achievement, as well as studies that question whether transitioning to middle school has lingering, rather than merely initial, adverse effects.

Benefits and drawbacks

The benefits of K–8 schools are being rediscovered in cities like Cleveland. Catholic schools in Ohio have used this model for decades. Although there is research that both supports and questions the higher academic outcomes of K–8 buildings, altering grade spans remains an option for districts looking to increase achievement or deal with declining enrollment numbers. Here’s a look at some of the benefits for school districts considering a transition to a K–8 building:

On the other hand, potential drawbacks include:

***

K–8 buildings boast research and anecdotes that support their promise as effective instruments of reform, but they also present significant potential drawbacks. For districts looking to improve achievement or trying to save money in the face of declining enrollment, reorganizing grade level configuration could be a practical solution.

The University of Kentucky may have lost the NCAA tournament, but Kentuckians can still take heart in their K–12 schools’ promising non-athletic gains. According to this new report, the Bluegrass State’s ACT scores have shot up since it began to implement the Common Core in 2011–12.

Using data from the Kentucky Department of Education, the study compared ACT scores for three cohorts of students who entered eighth grade between the 2007–08 and 2009–10 school years. The first group took the ACT—a state requirement for all eleventh graders—in 2010–11, immediately prior to CCSS implementation. They were therefore not formally exposed to instruction under the new standards. Cohorts two and three took the ACT in 2011–11 and 2012–13, after the introduction of CCSS-aligned curricula. They earned composite scores that were 0.18 and 0.25 points higher, respectively, relative to first cohort. The study authors report this gain as roughly equivalent to three months of additional learning.

The report rightly cautions against reading too much into these early findings. The short interval between Common Core implementation and the cohorts’ ACT scores reduces the effect the standards could have on student achievement. The authors also note that it is not clear whether the scoring gains could have been attributed to other systemic changes, such as new testing, accountability, and teacher evaluation models that were introduced concurrently with Common Core. Nevertheless, considering that Kentucky’s former state standards for math and English language arts both received a D rating in our State of State Standards report, the improving ACT results from Kentucky may be a sign of better things to come for more states across the nation.

SOURCE: Zeyu Xu and Kennan Cepa, “Getting College and Career Ready During State Transition Toward the Common Core State Standards,” American Institutes for Research (April 2015).