What makes Needles schools special? A recap of Fordham's Needles event in Dayton

Leaders from two Dayton high schools divulge the special sauce

Leaders from two Dayton high schools divulge the special sauce

Is there a special sauce that makes an urban high school great? This question and more were discussed at a community conversation on urban education at Dayton’s Stivers School for the Arts last week.

Some 150 or so Daytonians turned out to listen to the school leaders of Stivers and Dayton Early College Academy, who shared their thoughts on what makes their schools great. Both Stivers and Dayton Early College Academy were featured in Fordham’s Needles in a Haystack. Needles schools are high-minority, high-poverty urban public schools that produce uncommon results for their students. The Seedling Foundation helped to organize the event.

Needles panel discussion (from left to right): Dayton Public Schools superintendent Lori Ward, Erin Dooley and Liz Whipps of Stivers School for the Arts, Fordham's Checker Finn and Needles author Peter Meyer, Dave Taylor and Judy Hennessey of Dayton Early College Academy.

According to these school leaders, the recipe for a great urban school goes something like this:

3 cups of sense of purpose; 2 cups of enthusiasm; 1 cup of committed, talented teachers; 1 cup of high expectations; ½ cup of making learning “cool”; a dash of community support and a dash of parental engagement; and finally, a bowlful of “spit”—a “whatever it takes” attitude (in the words of Stivers principal Erin Dooley).

Yet this recipe isn’t identical for both schools. In fact, there are differences. Stivers, an arts magnet for the Dayton Public Schools, uses the arts to inspire a love of learning among its students. Through the arts, Erin Dooley asserts, students apply academics and make learning real. Meanwhile, DECA, a public charter school, has a laser-like focus on college readiness. When asked about DECA’s educational theme, principal Dave Taylor’s answer was trite and to-the-point: “You’re going to college.”

Despite noticeable differences in educational philosophy and organizational design (DECA is a charter; Stivers, a district school), the recipe—and their achievement results—are strikingly similar. At the core, it’s about culture, attitude, and expectations for these high-performing, urban high schools.

Why the shrinking middle class? According to E.D. Hirsch, the explanation is short and simple: Declining educational opportunity leads to fewer high-achieving students, which leads to greater income inequality, which leads to the decline of the middle class. Educational opportunity for only the privileged, therefore, polarizes a nation’s population and creates a society of haves and have-nots.

In his new article “A Wealth of Words”, Hirsch attempts to pinpoint where America’s education system has failed—and left in its wake, increasing income inequality. He identifies poor language arts instruction as the culprit. As evidence, Hirsch points to America’s history of declining and now stagnant SAT verbal scores. Starting in the mid-60’s, SAT verbal scores declined precipitously, reaching their nadir in the early 80’s and persisting at low levels until today. Citing a number of studies, Hirsch insists that changes in language arts teaching beginning in the mid 1940’s diluted students’ knowledge of grammar and vocabulary. These instructional changes, Hirsch suggests, correlate to falling SAT verbal scores.

To improve students’ verbal skills, Hirsch argues that we need to reform language instruction. As models of effective language instruction, he looks at, for example, the use of content-based instruction in second language instruction and how French preschools teach their youngsters language skills. Based on these examples, he offers three practical recommendations: Improve language instruction starting in preschool, classroom instruction that focuses on content knowledge, and a systematic approach to vocabulary growth across all grades and starting in preschool.

SOURCE: Hirsch, E.D. "A Wealth of Words." City Journal 23, no. 1 (Winter 2013). http://www.city-journal.org/2013/23_1_vocabulary.html.

Ohio’s teacher preparation programs, especially those run by public universities, select mediocre students. So say the data from the Ohio Board of Regents recent release of data on the performance of Ohio’s teacher preparation programs. This is the first publication of data on teacher preparation programs (or “ed schools”) that is required under House Bill 1 (2009).

Among the data released are admissions data, value-added scores of teachers who graduated, and teacher licensure exam scores. These data vastly improve the information we have about the quality of teacher preparation programs—and the students who attend them.

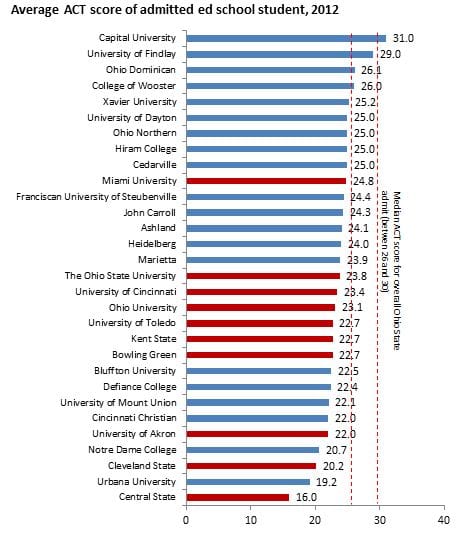

One indicator of the quality of the preparation program is the average ACT scores of admitted students. A higher average ACT score indicates greater selectivity and, most likely, higher program quality.[1] The chart below ranks the average ACT scores of students who were admitted in fall 2012. I exclude three universities because they have less than ten students in their teacher preparation program. In addition, 16 universities didn’t report an average ACT score and one ACT score appears to be an error. These teacher preparation programs vary in size, enrolling anywhere between 13 and 1,687 students.

Source: Ohio Board of Regents. Note: Public institutions are colored in red; private institutions are colored in blue. The range of ACT scores is 1 (low) and 36 (high). The statewide average ACT composite score for students admitted into a teacher preparation program is 22.75. The overall ACT average for Ohio students was 21.80 in 2012. The median ACT score of an admitted Ohio State University student is between 26 and 30. The median ACT score of an admitted Case Western Reserve University student is between 29 and 33.

A couple things stand out from this chart. First, private universities have higher quality admits. Capital University, a private university in Columbus, tops the list—a full two points higher than the University of Findlay, another private university. In fact, the top nine universities are private, and 14 of the top 15 are private. Only Miami University cracks the top 15.

Second, and more substantially, the mediocre-quality of students that enter teacher preparation programs stands out. Although average entrants into teacher preparation programs score marginally above the statewide average (23 versus 22 ACT composite), their scores don’t compete with the average Ohio State University entrant and are even less competitive with a prestigious university such as Case Western Reserve University. (Ohio State’s median composite score is 26 to 30; Case Western’s is 29 to 33.) In fact, only a few teacher preparation programs admit students near the caliber of the average Ohio State student.

The middling quality of students entering teacher preparation programs prompts questions: Why is this happening and what can be done to attract more talented teacher candidates? These are important questions, since they relate directly to the quality of Ohio’s future teaching force. Twenty-five or so states have already established fellowship programs aimed at improving the quality of its teaching force. North Carolina, for example, has a teaching fellows program that recruits and provides scholarships to 500 high school students who enroll in an in-state teacher preparation program. These scholarships are awarded based on academic merit. According to evaluative research, this program has successfully attracted higher-achieving students into teaching programs.

The data from the Regents demonstrate the need to attract high-achieving students into teaching. Ohio has slowly embraced Teach For America in Cincinnati, Cleveland, and Dayton, and it’s time to expand TFA. In addition, it may be time for Ohio to develop its own teaching fellowship program that attracts high-performing high school students into teaching programs. So, first hats off to the Regents for publishing these data, but now comes the hard part—acting on the data to improve the quality of teachers in the Buckeye State.

Postscript:

The National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ) released its 2012 State Teacher Policy Yearbook today. This report also indicates that admission standards to ed schools need to be raised. Ohio received C- on NCTQ's report card, just above the national average--a dismal D+. NCTQ rates states based on whether they have enacted policies that systematically prepare classroom-ready new teachers. One criteria is ed school admission standards.

[1] The Board of Regents does not report an admissions rate.

Earlier this month, Policy Matters Ohio released a short report examining how some charter schools evade Ohio’s academic accountability sanctions. Ohio has an academic “death penalty” for charter schools – if a school performs too poorly for too long, the state mandates its closure. The law is heralded as the toughest of its kind in the nation.

Since the law took effect in 2008, twenty charter schools have been subject to automatic closure. Yet, as Avoiding Accountability: How charter operators evade Ohio’s automatic closure law reveals, eight of these schools closed only on paper and soon after merged with other schools or reopened under new names, retaining the same physical address, much of the same staff, and the same operator. Two of the schools were closed for one year before reopening; six closed in May or June, at the end of a school year, and reopened in time for the start of the following school year. The report details the cases of each school’s “closure” and rebirth and provides information about their sponsors, operators, and academic performance.

Charter schools avoiding accountability is absolutely not okay, and Policy Matters is right to shed light on the issue. Many of the report’s recommendations are on the mark, and mirror recommendations Fordham (both as a policy advocate and authorizer of charter schools) has made over the years:

- The state should tighten closure laws so that sponsors, school boards, and operators cannot enter into new contracts to circumvent the law.

- Sponsors should be penalized for allowing schools to avoid accountability sanctions (in four of the eight cases the schools maintained the same sponsor before and after closure).

- The Ohio Department of Education should gain more capacity to oversee the charter sector, especially the closure process of sanctioned schools.

- The state should prohibit sponsors from selling services to schools they authorize, as this practice creates strong financial incentives for a sponsor to keep a failing school in operation.

These are admirable goals for continuing to shore up the quality of Ohio’s charter schools, and Policy Matters’ report illustrates that well. However, the report’s authors overplay the impact of the issue, condemning charters altogether because of these bad apples.

Specifically, there are three key pieces of information that would help round out and balance the report:

- Yes, 40 percent of schools marked for closure skirted the law, but these eight schools represent just two percent of all charter schools. It’s certainly hyperbole to suggest, as the report does, that that what transpired with these schools is evidence that Ohio’s overall charter law is “ineffective and weak.”

- Eighty-five, or 24 percent, of charter schools currently have a state rating of Excellent or Effective. These strong performers – and their sponsors and operators – should be lauded and certainly not penalized through excessive new regulations because of the actions of few.

- Eight percent of traditional district schools (159 buildings serving 105,000 students) have ratings of Academic Emergency or Academic Watch, the same as the failing charter schools featured in the report.

Academic accountability is an important issue for all public schools, charter and district alike. Policy Matters deserves credit for highlighting a loophole in the state’s accountability system, and likewise is correct to recommend smart changes to state law. However it is not accurate to allege that Ohio is not “serious about quality in the charter sector.” Ohio’s automatic closure law – even with its “loopholes” – remains the toughest in the country, and over the past four years state leaders have worked to increase oversight and accountability of charters.

Is there a special sauce that makes an urban high school great? This question and more were discussed at a community conversation on urban education at Dayton’s Stivers School for the Arts last week.

Some 150 or so Daytonians turned out to listen to the school leaders of Stivers and Dayton Early College Academy, who shared their thoughts on what makes their schools great. Both Stivers and Dayton Early College Academy were featured in Fordham’s Needles in a Haystack. Needles schools are high-minority, high-poverty urban public schools that produce uncommon results for their students. The Seedling Foundation helped to organize the event.

Needles panel discussion (from left to right): Dayton Public Schools superintendent Lori Ward, Erin Dooley and Liz Whipps of Stivers School for the Arts, Fordham's Checker Finn and Needles author Peter Meyer, Dave Taylor and Judy Hennessey of Dayton Early College Academy.

According to these school leaders, the recipe for a great urban school goes something like this:

3 cups of sense of purpose; 2 cups of enthusiasm; 1 cup of committed, talented teachers; 1 cup of high expectations; ½ cup of making learning “cool”; a dash of community support and a dash of parental engagement; and finally, a bowlful of “spit”—a “whatever it takes” attitude (in the words of Stivers principal Erin Dooley).

Yet this recipe isn’t identical for both schools. In fact, there are differences. Stivers, an arts magnet for the Dayton Public Schools, uses the arts to inspire a love of learning among its students. Through the arts, Erin Dooley asserts, students apply academics and make learning real. Meanwhile, DECA, a public charter school, has a laser-like focus on college readiness. When asked about DECA’s educational theme, principal Dave Taylor’s answer was trite and to-the-point: “You’re going to college.”

Despite noticeable differences in educational philosophy and organizational design (DECA is a charter; Stivers, a district school), the recipe—and their achievement results—are strikingly similar. At the core, it’s about culture, attitude, and expectations for these high-performing, urban high schools.

Why the shrinking middle class? According to E.D. Hirsch, the explanation is short and simple: Declining educational opportunity leads to fewer high-achieving students, which leads to greater income inequality, which leads to the decline of the middle class. Educational opportunity for only the privileged, therefore, polarizes a nation’s population and creates a society of haves and have-nots.

In his new article “A Wealth of Words”, Hirsch attempts to pinpoint where America’s education system has failed—and left in its wake, increasing income inequality. He identifies poor language arts instruction as the culprit. As evidence, Hirsch points to America’s history of declining and now stagnant SAT verbal scores. Starting in the mid-60’s, SAT verbal scores declined precipitously, reaching their nadir in the early 80’s and persisting at low levels until today. Citing a number of studies, Hirsch insists that changes in language arts teaching beginning in the mid 1940’s diluted students’ knowledge of grammar and vocabulary. These instructional changes, Hirsch suggests, correlate to falling SAT verbal scores.

To improve students’ verbal skills, Hirsch argues that we need to reform language instruction. As models of effective language instruction, he looks at, for example, the use of content-based instruction in second language instruction and how French preschools teach their youngsters language skills. Based on these examples, he offers three practical recommendations: Improve language instruction starting in preschool, classroom instruction that focuses on content knowledge, and a systematic approach to vocabulary growth across all grades and starting in preschool.

SOURCE: Hirsch, E.D. "A Wealth of Words." City Journal 23, no. 1 (Winter 2013). http://www.city-journal.org/2013/23_1_vocabulary.html.