The ADC off-ramp is already letting districts shortchange students

Last year, lawmakers caved to political pressure and created an easy off-ramp for the three districts currently under Academic Distress Commissi

Last year, lawmakers caved to political pressure and created an easy off-ramp for the three districts currently under Academic Distress Commissi

Last year, lawmakers caved to political pressure and created an easy off-ramp for the three districts currently under Academic Distress Commission (ADC) oversight: Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland. Each school board was charged with developing an academic-improvement plan containing annual and overall improvement benchmarks. The state approved these plans in December.

Districts are set to begin implementation of their plans at the start of the 2022–23 school year. But officials at Youngstown City School District recently noted that they also included goals for the current school year as a means of holding themselves “accountable.” According to an article in The Vindicator, nine of the thirteen benchmarks that can be measured thus far have already been met.

The article doesn’t examine these nine benchmarks in depth, but it does briefly mention a literacy goal for students in grades 2–5 and a math goal for students in grades 4–5. A quick look at Youngstown’s approved plan shows that these benchmarks are tied to NWEA MAP, a computer adaptive assessment used in schools across the nation. MAP assessments can be administered at any time (though they’re typically administered three times a year), so it’s definitely possible for Youngstown to measure progress this early. But the implication that meeting or exceeding these benchmarks so soon is a good sign “despite the Covid-19 pandemic” is misguided.

First and foremost, these goals are not rigorous. Consider the literacy benchmark for students in grades 2–5, which aims for students to meet an “individual expected growth goal” based on MAP. The percentage of students who meet this goal must gradually increase each year, from 32 percent during 2022–23 to 44 percent in 2023–24 and 57 percent by 2024–25. That seems like a reasonable increase until one digs a little deeper and finds that prior to the pandemic, 52 percent of Youngstown students met their growth targets in 2017–18 and 50 percent in 2018–19. Pandemic-caused learning loss is nothing to scoff at, but districts are back to in-person, full-time school. They have millions in federal relief funds to dedicate to catching students up. And yet, Youngstown won’t be accountable for getting the number of second- through fifth-grade students who meet their literacy growth goal above pre-Covid levels until three years after their new improvement plan takes effect. With in-person school back on, millions in relief funding, and a horde of intervention ideas floating around, the district should be working toward much more rigorous benchmarks rather than patting themselves on the back for reaching low targets.

Second, it’s important to keep in mind that these are growth goals. They do not measure whether students can read proficiently or have met grade-level state standards. Growth can and should be celebrated, but it’s not the same as proficiency. In fact, it’s likely that many students who meet their growth goals this year will need several more years of strong academic growth to read or do math on grade level. According to an in-depth look at state test results from spring 2021, students lost anywhere from one-half to a whole year’s worth of learning in math and between one-third and one-half of a year’s worth of learning in ELA compared to prior years. One year of solid growth simply isn’t enough to make up this ground—it must be sustained, and that should be the district’s focus right now.

We won’t know whether Youngstown schools have improved until we get full state test results in the fall. Report cards will offer a clearer look at growth—thanks to Ohio’s value-added measure—and proficiency numbers will shine a light on how many students are truly meeting grade-level standards. But in the meantime, it should worry parents and advocates that district officials and the media are already touting improvement. It’s bad enough that the state approved a plan with such lackluster benchmarks. But using some of those benchmarks to claim a semblance of victory before full implementation of the plan has even started? That’s not a good sign.

April is drawing to a close, and that (thankfully) means the end of tax season. Parents may have found this year’s paperwork more complicated than usual due to the “enhanced” child tax credit and advanced payments. One detail to which they had to pay attention was the reduction of the enhanced credit once specific income levels were hit—$75,000 for a single filer and $150,000 for joint filers—surely an effort to target the extra subsidy to lower-income families. Interestingly, married couples making double the income of single filers were treated as equals. That’s only fair, as incomes were the same on a per-taxpayer basis.

This got me thinking about the income limits Ohio places on eligibility for its income-based EdChoice scholarship, a state-funded program that offers assistance to parents seeking private school options. How does it treat dual-earning families?

As a quick refresher, Ohio offers EdChoice scholarships to parents whose household income is 250 percent or less of the federal poverty guidelines. For a family of four, the current eligibility cutoff is a pre-tax, gross income of $66,225. Families earning more than that are ineligible (though they could be eligible for “performance-based” scholarships). At face value, the current threshold seems fairly reasonable for a program that is supposed to support low- and middle-income families. After all, the average salary of an American worker is $58,000 per year.

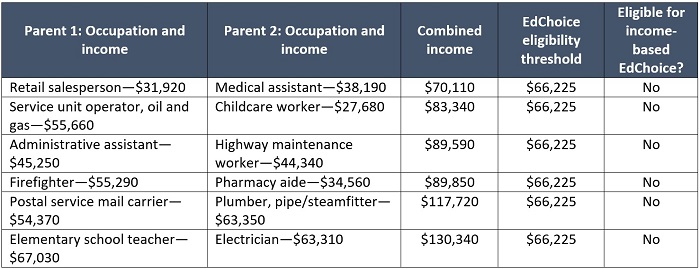

But this doesn’t mean that all families earning modest salaries have access to this program. Remember, Ohio looks at household—not per-capita—incomes to determine EdChoice eligibility. Thus, thousands of families where both parents work in middle-income jobs are out of luck. Consider just a few illustrative examples, using federal data on average salaries in various occupations.

Table 1: Illustration of dual-earning families’ occupations, salaries, and combined incomes

What this table shows is that EdChoice’s income requirements are far more restrictive than they initially appear. A family where dad works in an average-paying retail job and mom as a medical assistant could be over the eligible threshold. Same for a couple where one is a firefighter and the other a pharmacy aide. Postal worker and plumber? Teacher and electrician? Forget about it.

These are not deep-pocketed families who have thousands of dollars in disposable income to pay for private school tuition. Rather, these are folks working to put bread on the table, pay the rent or mortgage, and set aside money for college and retirement. They all pay their fair share of taxes. Many of them spend their weekends coaching youth sports or volunteering in their community. These hard-working parents deserve the opportunity to send their children to the school—whether public or private—of their choice. Yet EdChoice eligibility rules are unfriendly to dual-earning families, the employment arrangement of 58 percent of married couples with school-aged children.

State lawmakers have a couple options to straighten out this problem. The simplest approach is to raise the eligibility threshold to, say, 400 percent of the federal poverty guideline, thereby increasing, based on 2021 numbers, the income limit to $106,000 for a family of four. This would open private school opportunities for families where both parents earn salaries of up to $53,000 per year. Another possibility is to move away from poverty guidelines and tie scholarship eligibility to other federal policies such as income-tax brackets or eligibility for higher-education tax credits that distinguish between single and joint filers. For instance, any parent who files as a single or head of household making under $86,376—the low end of the middle tax bracket (24 percent) for singles—could be eligible for a scholarship. Couples filing jointly and earning less than $172,751, the analogous tax threshold, could likewise be eligible.

Expanded eligibility for income-based EdChoice scholarships would ensure that dual-earning families are treated fairly and given private school options. It’s also sure to be popular with parents and the broader public, as polls routinely find strong support for choice programs. With modifications to the income-based eligibility rules, legislators can make private schools an option for even more hard-working Ohio families.

A little over a month ago, the Biden administration proposed a new and unprecedented set of rules for the federal Charter Schools Program (CSP). The rules were met with fierce pushback from school choice advocates across the ideological spectrum, who rightly recognized that these rules would make it close to impossible to access funding that’s proven critical for start-up charter schools and high-quality networks looking to expand.

Last week, as the comment period drew to a close, a group of eighteen governors—including Governor DeWine—submitted a letter expressing their opposition to the new rules and calling on the Biden administration to remove the most troubling provisions. The full letter is worth a read, but here’s a quick look at its three strongest points.

1. The rules undermine parents’ right to choose

The governors waste no time in pointing out that these proposed rules would “undermine the authority of parents to choose the educational option best for their child.” And they are, of course, correct. Each year, millions of American families choose to send their children to a school other than the traditional public district they are zoned to attend. Parents make these decisions for myriad reasons, including what’s in the best interest of their child. Forcing parents to send their children to zoned schools just because they are district buildings, on the other hand, is forcing a decision that’s in the best interest of a system.

2. The rules exacerbate inequity

The proposed rules require CSP applicants to provide evidence that the number of charter schools they plan to open does not exceed the number of public schools needed to “accommodate the demand” in the community. In essence, it attempts to ensure that CSP funding is only awarded to charters that locate in cities where district schools are overenrolled and additional buildings are needed to pick up the slack. But overenrolled district schools are pretty much nonexistent right now, and tying charter grant funding to district enrollment does not, as the proposed rules suggest, prioritize equity. Rather, it merely limits opportunity. As the governors aptly point out, charter schools nationwide enroll more students of color and more economically disadvantaged students than their traditional public school counterparts. Limiting the growth of schools that give low-income and minority students opportunities that might not exist otherwise can and will exacerbate inequity.

3. The rules were proposed without proper engagement

The proposed rules emphasize how important it is for charters to collaborate with families and communities. In fact, they go so far as to criticize charters for failing to “fully engage” stakeholders. It’s ironic, then, that the Biden administration failed to conduct any meaningful engagement with the charter community prior to proposing these new rules. The governors note that unlike previous rule proposals, which have offered the public a comment period of at least sixty days, this comment period was limited to just one month. Unleashing new rules without warning and without giving advocates and stakeholders a proper chance to voice their concerns is the exact opposite of what the Biden administration claims is best practice.

***

It’s hard to see the proposed CSP rules as anything other than an attempt to limit charter growth. If this were about doing what’s best for kids, then federal officials would have made sure to engage with the charter community prior to making such drastic changes. Rather than prioritizing district enrollment, they would have acknowledged that charter schools serve more students of color and economically disadvantaged students, they often perform better than their district counterparts, and students enrolled in traditional public schools benefit from the existence of charters. And they definitely wouldn’t have attempted to use rulemaking procedures to limit the choices available to American families. Kudos to Governor DeWine and the other seventeen governors for speaking up on behalf of charter schools and the students they serve.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Students awarded EdChoice scholarships benefit from Ohio’s regulatory and accountability system for school-choice programs.

Ohioans rely on statutory and administrative codes to ensure that all schools meet basic quality standards for students.

Accountability is a fundamental issue in a lawsuit filed against the state over the constitutionality of the EdChoice Scholarship Program. The suit alleges nonpublic school providers are not accountable for the state dollars they receive. This assertion is inaccurate. School providers are accountable both to the state and to the families of scholarship recipients.

EdChoice providers are schools chartered by the State Board of Education to—at the very least—assure a high-quality general education. Schools must either complete the chartering process directly with the state, or be accredited by associations in which their standards are reviewed by the State Superintendent’s Advisory Committee on Chartered Nonpublic Schools and approved by the state.

The state’s operating standards applicable for EdChoice providers are markedly similar to those of public schools. Other required statutory and administrative code provisions are state mandated assessments, including the third grade reading guarantee and graduation tests, course content requirements, health and safety standards, requisite hours of instruction, anti-discrimination provisions, and mandatory employee background checks.

Additionally, EdChoice providers follow a rigorous application process with the Ohio Department of Education, which uses records to monitor compliance with a host of records related to school buildings, staff, volunteers, admission policies, fire inspections, and food services licenses. Schools are required to have these records available for compliance reviews, announced or unannounced, by state employees.

But it’s not only compliance that makes private-school scholarship programs accountable. EdChoice and other scholarship programs give parents a meaningful way to hold schools accountable for their children’s education. If parents are dissatisfied, they are empowered to leave—along with their funding.

Ultimately, EdChoice providers are most directly accountable to the students and parents for whom they serve.

But let’s remember these providers are private schools that garner public dollars—not by default—but only when parents independently choose to enroll. Moreover, scholarship funds cover just a portion of the total cost to educate students. As such, they should not be regulated exactly as public schools are. After all, for parents to have a diversity of school-choice options, nonpublic schools should not be mirror images of public schools.

Larry Keough is the associate director for education at the Catholic Conference of Ohio and legislative advocate for Catholic schools.

Can children learn to read via fully online instruction? Not long ago, this question was mainly a scientific curiosity or the stuff of sometimes-rancorous political debate. With the coming of Covid-19 and extended stretches of widespread remote learning, it took on an urgency that demanded an answer. According to new research published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, the answer is yes—but with a number of important caveats.

In 2019, University of Washington (UW) professor Jason Yeatman created a two-week in-person summer program that was part reading boot camp for five-year-olds and part neuroscientific research project to assess the teaching method being used. While the method was touted as groundbreaking science, it just seems like good old fashioned phonics with a side order of brain imaging. It also made use of small student-to-teacher ratios, highly qualified and high-energy instructors, manipulable materials to reinforce instruction, and a strong social aspect to bond the young participants. Sessions alternated between full-group and smaller breakout sessions during the day. Think Sesame Street live. Initial results were promising, but hopes for another year of data were dashed in 2020 due to the pandemic. Yeatman and his team quickly adapted—and while no one got their skull scanned via Zoom, the researchers were able to morph their teaching method into a fully online version. Even the social aspects and session structures.

Participants were recruited from UW’s existing group of voluntary test subjects and had to be between five years old and five years and four months old, have no diagnosed neurological or sensory conditions, speak English as the primary language at home, and have demonstrated no ability to read prior to the start of the new online reading camp. Phonological awareness and letter-sound knowledge, the two best predictors of reading acquisition during the first two years in school as concluded by a 2020 meta-analysis from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, were the exclusive focus of the camp’s teaching method. There were 116 children participating in the study, with eighty-three receiving the two-week treatment and thirty-three receiving no reading instruction, having gone through the full recruitment process but ultimately declining to participate in the camp. This does raise questions about why families would choose not to participate—children staying with relatives, kids attending daycare/preschool elsewhere, etc.—and whether those reasons could have impacted the outcome, but no data were collected on that.

The two groups did not differ significantly on observable measures, however. For both groups, the average parental education in years was roughly equivalent to a four-year college degree, with a wide range extending from elementary- to postgraduate-level degree completion. Socioeconomic status was measured via income-to-need ratio. Both groups included families at or below the federal poverty line, as well as families into the upper levels of wealth. Each group was approximately half boys and half girls. No racial or ethnic breakdown was provided.

Treatment children received a kit prior to the camp, which included workbooks and manipulatives like stacking blocks and modeling clay. High speed Wi-Fi and enabled devices were provided to any participants who did not already have them at home. Sessions were administered by three teachers with a bachelor’s degree in either education, linguistics, or speech and hearing sciences and who had prior experience teaching English to young children in previous lab projects. They received two weeks of training prior to the start of camp. The camp was conducted in fourteen waves of six participants each over the period of fall 2020 to summer 2021. It is interesting to note that the children were receiving “various and constantly changing” levels of formal schooling during this time, due to the pandemic. The two-week camp was held five days per week for 2.5 hours per day via Zoom. Two teachers taught each daily session, with each teacher primarily instructing three children every day, and those small groups were mixed and counterbalanced on different days so that each child became familiar with all the others. Each day included at least one full-group activity. Parents and other caregivers were instructed to assist their children with logging in and preparing the daily materials to be available. They were instructed to stay within earshot in case their children needed assistance but were told not to provide or prompt answers and to keep siblings away as much as possible. There were some cases of parental overinvolvement, which resulted in email and phone-call reminders from instructors of the proper level of interaction. No specific guidelines were provided to the families regarding additional reading-related activities outside the camp; however, they were asked to report any such activities in a post-camp survey.

Achievement and progress were measured via two pretests and two posttests (one standardized, the other not) on skills related to reading and the effect of the training program on those skills. For the control group, the pre- and postsessions took place two to three weeks apart to match the timeline of the treatment group.

While treatment and control group students did not differ significantly in their baseline pretest scores, treatment group students showed significant boosts on the posttests in the specific skills that were taught in the online sessions. These include phonological awareness and lowercase letters’ names and sounds. Interestingly, the data show increases in some reading skills that were not taught directly—such as uppercase-letter sounds and pseudoword decoding—among treatment-group students. Control group students did show small but not-significant improvement on uppercase-letter sounds, lowercase-letter sounds, rapid automatic naming, and expressive vocabulary. No correlations were found between these improvements and parental education level, and only two skill increases were found to correlate with socioeconomic status.

It feels a little odd after more than two years of pandemic disruption to read a research paper whose findings suggest that maybe we can make this online learning thing work after all—especially when members of the research team go on to suggest that it may even work for kids who take online classes by choice. Quelle surprise. This model is live, small group, super interactive, conducted by highly trained teachers. In this limited form, it resembles high-dosage tutoring more than it does “school.” More and varied research on what makes for successful online teaching for more children is required, but we’ve got a lot more data available than we’ve ever had before, as well as many examples of how it should not be done. This is at least one model upon which we can focus to figure out once and for all how do it right for anyone who wants it for any reason.

SOURCE: Yael Weiss, et. al., “Can an Online Reading Camp Teach 5-Year-Old Children to Read?” Frontiers in Human Neuroscience (March 2022).

While not as rapidly embraced as its math and ELA cousins, which have great merit, a new set of science standards has slowly gained traction in a majority of states. And although we at Fordham do not love the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), they and their close approximations are becoming the norm. If states are going to adopt these standards and stick with them, then it makes sense for schools and districts to align their instructional materials and teaching practices to them. A recent research brief from WestEd tackles the important next step by evaluating the efficacy of one particular set of materials.

WestEd’s team conducted a controlled trial of the Amplify Science Middle School (ASMS) physical science curriculum, developed by scientists at the University of California–Berkeley in collaboration with Amplify Education. Data came from fifteen schools in three districts across two states during the 2019–20 school year. The districts varied in size and served diverse student groups. The researchers paired schools based on their demographic characteristics and prior student performance on state math and ELA tests and then randomly assigned schools, within each pair, to the treatment or the comparison group. The study included eight schools in the treatment group and seven in the comparison group, with a total of twenty-eight teachers and 1,780 students (the original sample was larger but, unfortunately, had to be limited to classes that completed the curriculum prior to pandemic closures).

Teachers in the treatment group implemented the ASMS curriculum and received a total of twenty-four hours of training from the Berkeley developers. The curriculum package includes a digital platform for students and teachers, along with materials for hands-on activities, that being an important element of NGSS. Students interact with physical materials and within a digital workspace that provides access to custom-written science articles, simulations, and design tools. The lessons follow an instructional sequence meant to build students’ proficiencies with NGSS performance expectations over time, and the study comprised two ASMS units: the structure and properties of matter and chemical reactions. Teachers in the comparison group taught the same units aligned to the same NGSS-influenced standards but used a variety of non-ASMS curricula that included off-the-shelf and district-created permutations. Student learning was measured using an assessment developed by the WestEd team that focused on the three dimensions of science learning articulated in the NGSS. Curriculum use and details on instruction were measured using weekly teacher logs and a final survey.

Results show that treatment students scored 7.3 percent higher on the assessment than did students in the comparison schools. The results were similar across gender and racial and ethnic groups and for students with different prior math and literacy achievement. The estimated effect size of 0.36 is equivalent to the average student in the treatment schools improving a massive fourteen percentile points (moving from fiftieth to sixty-fourth percentile) relative to the average student in the comparison schools. Treatment group teachers reported high levels of positive engagement and satisfaction: More than 80 percent agreed that they and their students benefited from using ASMS curricular materials, 88 percent reported that ASMS supported them in engaging students in science discourse, and 54 percent reported that using ASMS changed the way they taught science. Unfortunately, an analysis of differences between the instruction given in treatment and comparison classrooms was not complete in time to be included in this publication.

Experience tells us that not all instructional materials are created equal, and attention to curricular quality is a welcome development. The more rigorous analyses of student outcomes via various curricula, the better.

SOURCE: Christopher J. Harris, Mingyu Feng, Robert Murphy, and Daisy W. Rutstein, Curriculum Materials Designed for the Next Generation Science Standards Show Promise: Initial Results From a Randomized Controlled Trial in Middle Schools (San Francisco, CA: WestEd, January 2022).