Can Ohio clean up its teacher pension mess?

Ohio’s teacher pension system is woefully underfunded, imposes significant costs on teachers and schools, and shortc

Ohio’s teacher pension system is woefully underfunded, imposes significant costs on teachers and schools, and shortc

Ohio’s teacher pension system is woefully underfunded, imposes significant costs on teachers and schools, and shortchanges those who decide to change professions or move to other states. Retirees, unhappy with their benefits, have commissioned a third-party investigation into the system. Bellwether Education Partners, a national think-tank, recently gave Ohio’s traditional pension plan an F, citing how poorly it serves teachers and taxpayers.

What to do? One possibility is to slash benefits and extract even more from teachers and schools to pay down the system’s $21 billion in unfunded liabilities—the shortfall in its assets versus pension obligations. This approach would be wildly unpopular, would suck money out of classrooms and teacher pocketbooks, and wouldn’t solve the underlying problems with administering the teacher pension system. Another alternative is bailout—injecting billions into the pension fund to cover its debts. But this would raise the specter of moral hazard, i.e., reinforcing the same behaviors that shipwrecked the system in the first place. Of course, it would also require huge sums of money, funded by cuts to other government programs or higher taxes.

The quicker we forget those options, the better, along with reckless pension obligation bonds (covering debt by issuing more debt). Fortunately, there are more sensible solutions that would put Ohio on stronger footing. Let’s take a look at three alternatives:

Option 1: Switch the default option to the defined contribution (DC) plan. Ohio is one of a handful of states that offers new teachers a choice in retirement plans. They can opt into one of three plans. Briefly, they are as follows:

By default, newly hired teachers participate in the DB plan if they do not select a plan within their first year of work. Three in four don’t make an affirmative choice, and as a result, the vast majority end up in the DB. In a 2021 Fordham report, pensions expert Chad Aldeman made a strong case for changing the default to the DC plan, something Florida did five years ago. His calculations show that the DC plan provides today’s entering teachers—no matter how long they plan to work—more retirement wealth than the DB option. If the goal is to give new teachers superior benefits, switching the default is a no-brainer. This policy option would retain the DB and hybrid plans for entering teachers who might prefer them.

Option 2: Close the DB plan to new teachers, and offer a cash balance (CB) plan. Ohio does not currently offer this option, but the state could require new teachers to enroll in a CB plan, as Kansas did in 2012. This structure has features of both DC and DB plans. Like a DC plan, contributions are deposited into individual accounts. But unlike a DC plan, where teachers make investment decisions, the state invests on their behalf and deposits interest each year into accounts, the rate of which can be tied to the “risk-free” return (e.g., 3 percent). The state can still invest in riskier assets, and in years of strong returns—for instance, 7 percent—it may choose to pay a higher interest rate or set aside gains to offset losses in a downturn. When teachers retire, the savings accumulated in their accounts are annuitized, and the system makes payments for the duration of their retirement.

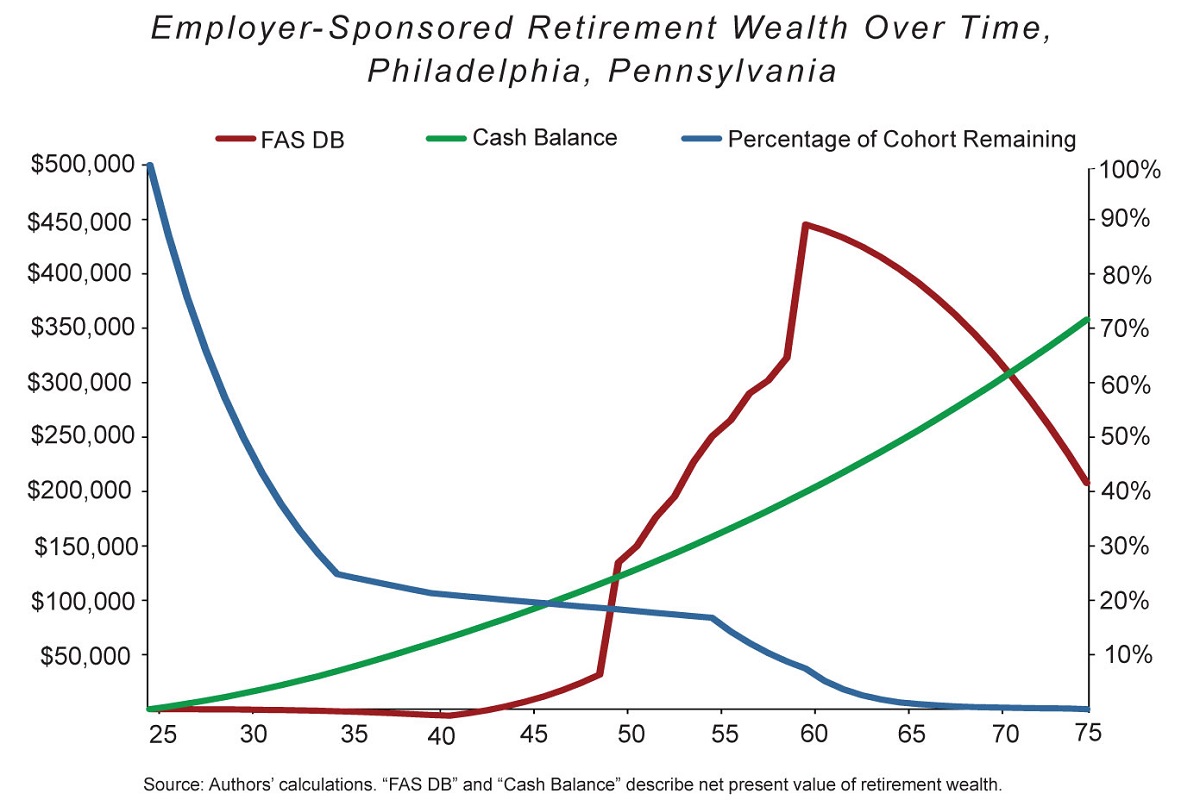

In contrast to a traditional pension, CB plans treat short- and medium-term teachers fairly. As the figure below illustrates, CB plans “smooth” the accrual of retirement benefits over a teacher’s career instead of backloading them. Thus, teachers who separate early have more retirement wealth when they leave. In the bottom left portion of the chart, we see a “wedge” between the CB line in green and the DB line in red. This represents the gains under a CB plan in wealth for the roughly 80 percent of teachers who work for less than twenty-five years in this school system. Though a minority, entering teachers who work more than twenty-five years would receive less under a CB than DB plan. That occurs because a CB plan doesn’t “cross subsidize” older teachers at the expense of younger ones.

Source: Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, “Modernizing Teacher Pensions,” National Affairs (2015).

Source: Josh McGee and Marcus Winters, “Modernizing Teacher Pensions,” National Affairs (2015).

Option 3: Close the DB plan to new teachers, and offer a DC plan. In an effort to attract a more mobile workforce and to reduce legacy costs, this is exactly what U.S. businesses have done over the past three decades. Today, approximately 80 percent of private-sector workers with retirement benefits are in a DC plan. State governments, perhaps because they don’t compete in the same way as private companies, have been slower to shift from pensions. Alaska is the only state to have closed its DB plan for teachers and now offers only a standalone DC option. A few other states, however, have transitioned to DC plans for other state workers.

As noted above, Ohio already administers a DC option for teachers—and it’s a pretty good deal at that. Yet very few participate because of the state’s default policy and perhaps limited understanding among entering teachers about retirement options. Much like the CB plan above, benefits in the DC plan accrue evenly across a teacher’s career and are fully portable. Thus, teachers who separate early have considerably more retirement wealth than in the DB plan. However, unlike the CB plan, which guarantees a minimum interest rate each year, teachers directly control the investment decisions in a DC plan. Depending on those choices—which can be wisely vetted by plan administrators—they may generate larger or smaller returns than the interest rate in a CB plan. From the view of the state, a DC plan is the most straightforward and predictable option. It bears no investment risk and no complicated actuarial calculations are needed to project pension obligations. In fact, there are no unfunded liabilities at all in a DC plan.

The notable drawback to a DC plan is that retirees could outlive their savings. While there is an annuity feature for Ohio’s DC participants, their safety net would be bolstered if they received social security, as well. Ohio teachers do not participate in the program, and if the state moves in the direction of offering a standalone DC plan, it should consider enrolling teachers in social security. The program offers a baseline amount of income for life, protecting retirees who live well into their golden years. Of course, the catch is that benefits are paid for through payroll taxes levied against employers and employees (12.4 percent combined). Ohio would need to lower its DC contribution rates to compensate for the new taxes. In terms of process, teachers would need to vote to participate in social security.

* * *

The traditional pension fails to justly compensate a large portion of Ohio teachers for their work every year in the classroom. It’s massively expensive and incredibly complicated. Over the past decade, retiree benefits have been in flux. The politics of pension reform won’t be easy, and there’d be much to sort out, especially if the state closed its DB plan (figuring out how to address unfunded liabilities). But all is not lost. Policymakers have options that can make retirement more fiscally sustainable and fairer to a next generation of Ohio teachers. It’ll take much hard work, but kicking the can down the road is a short-sighted option.

In late March, the Ohio Department of Education announced a grant program aimed at developing and expanding tutoring for K–12 students in the wake of pandemic-caused learning losses. The program specifically focuses on high-dosage tutoring (HDT), which research shows can produce large learning gains for students. The Department plans to distribute up to $20 million in federal Covid relief funding to both public and private two- and four-year colleges and universities. Only institutions of higher education (IHEs) that have teacher preparation or education programs are eligible for funding, but IHEs that don’t have such programs can still participate by partnering with those that do.

At first glance, it might seem odd for the state to provide tutoring funds to postsecondary institutions rather than K–12 schools. But there are two reasons why state leaders were wise to structure the program in this way. First, it addresses one of the biggest barriers to establishing an effective, statewide tutoring program: finding enough tutors. Schools often struggle to recruit the adults needed to maintain a robust tutor pipeline. That’s especially true for HDT, which is an intensive model that requires one-on-one or small-group instruction at least three days a week. By tapping into IHEs, Ohio is following in the footsteps of other states that leveraged college students to meet pipeline demands. Second, by focusing on IHEs with teacher preparation or education programs, Ohio can meet two needs at once. Not only will K–12 schools have access to a robust pipeline of tutors, teacher candidates who serve as tutors will gain hands-on instructional experience and training.

By preempting the tutor pipeline issue, Ohio has at least partly addressed how to make HDT possible on a broad scale. But what about the other side of the equation, which is making HDT effective? Grant awardees weren’t notified until mid-May, which means programs will likely gear up this summer at the absolute earliest. As such, it’s impossible to gauge effectiveness yet. But a quick look at the program design requirements outlined in the state’s request for applications (RFA) indicates that state leaders took some good first steps at setting up HDT programs for success. Here’s a look at a few of the highlights.

Curriculum and instruction

The RFA calls for colleges and universities to focus on math and/or literacy tutoring for K–12 students that’s aligned to Ohio’s Learning Standards and uses evidence-based, high-quality instructional materials. The state doesn’t identify specific curricula or materials that must be used, but it does offer several resources. Applicants must also include details on how they plan to use data-driven decision-making to maximize the number of students they serve, including identifying students who are considered most at-risk.

Training and supporting tutors

There aren’t a ton of specific guidelines for applicants in this regard, but the RFA does specify that tutors should have background checks, and that those who have been “appropriately trained in effective pedagogy and demonstrated content knowledge” should be given “priority” in hiring decisions. As for tutor training, it should cover topics such as effective math teaching practices, evidence-based literacy strategies, strategies for student behavior management, data collection and progress monitoring, and tutor-student relationships.

Operations and collaboration

The RFA requests details on several operational aspects of proposed programs. For example, applicants are asked to provide an anticipated schedule that describes the frequency, duration, and location of tutoring sessions, as well as the number of students who will be tutored. They must also establish a process for how the K–12 school and postsecondary institution will communicate student progress to teachers and parents. In terms of collaboration, IHEs and partnering schools are tasked with designing programs to be mutually beneficial for K–12 students (who receive tutoring services) and participating college students (who could benefit from field experience, stipends, volunteer hours, course credit, or loan forgiveness).

Sustainability and evaluation

The downfall of many grant programs is that once funding runs out, the program ceases to operate, even if it’s had a positive impact on students. To avoid this, IHEs and their partner schools are tasked with working together to identify which elements of the program could be sustained after the grant. As for evaluation, IHEs and their partner schools must develop a monitoring system that gauges the effectiveness of the program, including student outcomes in math and literacy. Grantees are required to participate in state evaluation activities.

***

State leaders deserve kudos for not only recognizing the potential of HDT, but for taking steps to address tutor pipeline barriers and setting clear standards for applicants. Now, the focus must shift to ensuring that HDT programs are implemented rigorously so that students can reap the benefits.

In 2015, reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) included a provision asking states to ensure that all students have equal access to qualified and effective teachers. States were given a lot of leeway to determine quality and effectiveness, but were required to submit a raft of data to the federal government to document their chosen avenues. Six years later, the collection and reporting processes for those data are the topics of a policy brief by the National Council on Teacher Quality (NCTQ). Here’s a look at their analysis with a focus on Ohio.

There are nine areas of data reporting with which NCTQ is concerned: Does the state report on the proportion of out-of-field teachers in a way that is approximately aligned to research consensus? Does the state report on the proportion of inexperienced teachers in a way that is approximately aligned to research consensus? Does the state choose to report on teacher effectiveness using definitions/methodology grounded in research? Has the state published data at least once in the last two years? Does the state publish this data at the state, district, and school level? Does the state disaggregate their reporting by Title I and race/ethnicity? Does the state report how individual LEA’s compare to the state average? Does the state follow best practices for accessibility in data reporting? Does the reporting include the ability to download or export the full data set?

The Buckeye State gets full marks for reporting data in five of these nine areas. Most importantly are the three measures of teacher quality for inexperienced, out-of-field, and ineffective teachers. NCTQ analysts downgraded many states for their questionable definitions of effectiveness and for collecting data that they do not make public, but Ohio is one of eighteen states that both defines effectiveness in accordance with research-based practices and publicly reports the data it collects. The timeliness and ease of exportability of data publications are also deemed up to scratch in Ohio. The state received only partial credit for data disaggregation, as we lack the finest-grained school-building-level and racial-minority-status breakouts. In the negative column, Ohio does not compare local education agencies’ data directly to the state average, nor does it follow NCTQ’s three best practices for accessibility in data reporting.

All of this serves to put Ohio mid-pack in NCTQ’s analysis. Pennsylvania fares worst, meeting none of the nine benchmarks even partially; Oklahoma gets partial credit in just one category. Colorado is at the top in terms of passing grades, missing only disaggregation of data at the school building level. Florida, Rhode Island, and Washington State, while varying in their overall rankings, are all singled out for specific positive aspects of effectiveness definitions, data breakouts, and accessibility/comparability of their reports.

Of the four recommendations for states included in NCTQ’s brief, only one applies directly to Ohio: improving how data is reported so it is clearer how schools and districts fare in relation to the state average or “other obvious points of comparison.”

All in all, it seems Ohio took the less-than-crystal-clear guidance provided by the federal government six years ago and did a reasonably good job in actualizing it. How all of this compliance theater contributed to the actual goal of ensuring “that all students have equal access to qualified and effective teachers” is the province of other analyses.

SOURCE: Shayna Levitan, Shannon Holston, and Kate Walsh, “Ensuring Students’ Equitable Access to Qualified and Effective Teachers,” National Council on Teacher Quality (April, 2022).

Reams of research have reported contradictory outcomes for students with disabilities (SWDs) who are taught in general education classrooms alongside their non-disabled peers versus learning in settings with only SWDs. A new report focuses on teacher certification as a possible mechanism to explain the variations in outcomes.

J. Jacob Kirksey from Texas Tech University and Michael Lloydhauser from the University of California, Santa Barbara use data from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study—Kindergarten Class of 2010–2011 (ECLS-K) to identify 2,370 unique SWDs and observe them over three school years. Students were included if they had an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) on file with their school in kindergarten, first, or second grade and if data indicated that they were primarily educated in general education classrooms instead of specific classrooms for SWDs. While the original ECLS-K sample was nationally representative, the researchers do not provide a breakdown of their final sample on any demographic criteria.

Students’ academic achievement was assessed in math and reading in both the fall and spring of kindergarten as well as the spring of the next two years. The mathematics assessment included questions on number sense, properties, and operations; measurement; geometry and spatial sense; data analysis; and patterns and functions. The reading assessment had questions on print familiarity, letter recognition, and recognition of common words. Analysts used the scores to construct value-added estimates of student achievement over time. Teachers reported their certification in elementary education, early childhood education, some version of English as a second language/bilingual education, or special education. Single-credential teachers abounded in the sample, but a small minority had dual credentials in special education and one of the other areas. Kirksey and Lloydhauser compared academic outcomes for SWDs whose teachers only had special education certification, SWDs whose teachers only had a single general education certification, and SWDs whose teachers had dual certification in special and general education.

They find that SWDs with teachers holding only a special education credential fared worse in math (0.14 standard deviations) compared to their SWD peers whose teachers had a single elementary education certification. There was no difference observed in reading achievement. Dual-certification teachers, likewise, seemed to have no observable impact on SWD student achievement in this initial analysis.

A second model looked at school-level fixed effects and found no difference in achievement for SWDs based on teacher certifications. The authors’ third and preferred model combined school and child fixed effects (largely eliminating “school and child-level confounding bias”) and found positive, statistically-significant results (0.09 standard deviations) linking dual certification to higher math outcomes for SWDs.

As long as parents continue to want their children with IEPs to learn in general education classrooms, the question of how best to serve those students will loom large. This research offers few answers. Variations in disability type, size and composition of different classrooms, and out-of-classroom supports are all unmeasured factors which could have influenced the observed outcomes, and thus are worthy of deeper investigation.

SOURCE: J. Jacob Kirksey and Michael Lloydhauser, “Dual Certification in Special and Elementary Education and Associated Benefits for Students With Disabilities and Their Teachers,” AERA Open (April 2022).

Earlier this summer, Ohio’s state superintendent Paolo DeMaria announced his retirement, effective in September. We at Fordham wholeheartedly salute DeMaria for his work on behalf of students and his leadership in helping schools navigate the challenges of the past year.

The state board of education is tasked with finding his replacement, and attracting a high-caliber education chief should be a top priority. To be sure, this won’t be a cushy job for the faint-of-heart. He or she will need to traverse heated political debates and win support from strong-willed lawmakers and board members. The state superintendent will also oversee the work of the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), an agency that implements and enforces education laws. The good news, though, is that Ohio has lots going for it in the area of K–12 education. The next superintendent will have abundant opportunities to make a mark on policies that impact Ohio’s two million public and private school students. Consider five such opportunities.

Opportunity 1: Cement into place a revamped school report card. After months of debate, lawmakers recently overhauled the state’s school report cards. Supported by a number of education groups (including Fordham), the new system should yield ratings that are fairer to schools and provide the public with easy-to-use information about school quality. While the legislature has created the statutory framework, the state board and Ohio Department of Education (ODE) will need to iron out some of the details in the coming months. Most notably, they’re tasked with setting rigorous but attainable “grading scales” for each report card measure and ensuring clear presentations of the ratings and underlying data. This technical work must be done right. But just as importantly, the next state superintendent will have to clearly explain the crucial role report cards play in a healthy, responsible, and transparent public school system. That type of vocal leadership can build the public support and confidence needed for the new report cards to be successful.

Opportunity 2: Energetically advance the state’s early literacy initiatives. Recognizing the link between early literacy and students’ long-term success, Ohio lawmakers passed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee in 2012. Its most well-known provision is mandatory retention when students cannot demonstrate fluency on third grade reading assessments. But there are other crucial dimensions to the policy that help ensure that children receive the supports needed to reach that vital benchmark. These include required parental notification and reading plans for off-track children, and intensive interventions for retained students. Despite its importance, the policy has faced political pushback and uneven implementation. The next superintendent could jump-start this vital initiative by pushing for rigorous implementation and voicing support for early literacy.

Opportunity 3: Lay a solid foundation for the state’s brand-new enrichment ESA. In a state budget bill chock-full of exciting initiatives, one of the most tantalizing is the creation of an educational savings account (ESA). This program will open afterschool and enrichment opportunities for low- and middle-income students by providing $500 per year that parents can spend on approved activities. The ESA holds much promise to narrow “opportunity gaps,” but its future beyond 2023 is uncertain because it’s being funded through temporary federal relief dollars. To sustain the program over the long-haul, lawmakers will likely need to commit state money and may even need to increase the outlay to meet parent demand, as dollars could easily run out if applications exceed the appropriation. Getting the program off on the right foot will be critical, and ODE will play a key role in making sure that happens. The agency will accept applications, select a vendor that creates the accounts and monitors spending, and inform parents about acceptable uses of the dollars. Active involvement from the state chief could help position the program for growth in the years ahead.

Opportunity 4: Push for excellent career and technical education and work-based learning. Recognizing the need to strengthen the technical skills of Ohio students, state policymakers have ramped up support for CTE. In the recently passed budget, lawmakers allocated $20.5 million for programs that reward schools when students earn industry recognized credentials. These funds will supplement the already generous categorical “add-on” dollars that schools have long received when pupils take various CTE courses. With such goodwill, the next state superintendent should have plenty of room to showcase high-quality CTE and workforce development initiatives. By the same token, he or she may need to put their foot down at times to ensure that these programs are truly opening doors to great careers—not rewarding lower-level skills that don’t allow students to stand out and get ahead in the workplace.

Opportunity 5: Champion great educational options for all Ohio students. Ohio has a proud history of pioneering educational choice, but recent policy developments have accelerated the move to empower parents and students. Today, Ohio has a plethora of public school options, which include district-run magnet schools, regional STEM schools, and public charter schools. Interdistrict open enrollment is an option for most Ohio students. High school students can take college-level courses via College Credit Plus or CTE courses at their local joint-vocational school. With expanded eligibility for state-funded scholarships, more Ohio students than ever have private-school options. In the most recent budget, lawmakers even recognized the dedication and contributions of parents who homeschool their children by offering modest tax relief. The next state superintendent will have ample opportunity to champion a rich plurality of educational options and support the growth of choices that meet the unique needs of all Ohio students.

***

Just like the president has many hats, the state superintendent plays many roles as well. He or she will need to work diplomatically with lawmakers and the state board to get things done. They’re responsible for supervising one of the nation’s largest and most diverse school systems, and for communicating state education priorities to the broader public. It’s a big job with big opportunities. And for someone who is ready to make a difference in the lives of millions of students, it might just be the job of a lifetime.