Four ways Ohio can prepare for the likely school funding crunch to come

With the economy in free fall due to the coronavirus pandemic, schools across the nation are very likely to face significant fiscal challenges.

With the economy in free fall due to the coronavirus pandemic, schools across the nation are very likely to face significant fiscal challenges.

With the economy in free fall due to the coronavirus pandemic, schools across the nation are very likely to face significant fiscal challenges. While a sharp v-shaped recovery is possible (here’s hoping) and Congress may pump out additional stimulus cash (more probable), state and local leaders still need to prepare for the economic headwinds.

In a recent webinar, school finance expert Marguerite Roza of Edunomics Lab discusses the potential impacts on schools. They are likely to suffer revenue declines, while also facing pressures that make it hard to contain costs during a recession (e.g., more low-income students and less attrition of veteran teachers). To help prepare for the budget crunch, Roza offers some concrete suggestions such as immediate hiring freezes and reopening employee contracts. Those are an excellent start, especially if you’re a local superintendent. Yet in the coming months, Ohio policymakers will need to rethink, and possibly rework, a number of state funding policies in light of new fiscal realities. Where to begin? This piece offers four basic ideas.

First, set realistic expectations for school funding.

To his credit, Governor DeWine has been very open and frank with Ohioans about the public-health crisis and his rationale for taking action to mitigate it. Likewise, state leaders will need to strike a similar tone when discussing the budget challenges that lie ahead and their effects on school funding. In the short term, the federal stimulus and Ohio’s rainy day fund should help the state absorb the impacts this year and possibly next (FYs 2020 and 2021). But state policymakers will also need to start planning for the next biennial budget, which will be debated in spring 2021. If the economy continues its free-fall, the state will be hard-pressed to maintain current school funding levels, much less pay for the large, across-the-board funding increases proposed in the Cupp-Patterson plan, or find the extra dollars that can support other well-intended reforms such as eliminating funding caps. Instead, policymakers will need to ensure that the public and school leaders have realistic expectations about what the state can afford.

Second, emphasize the state’s special responsibility to support less advantaged students.

The pandemic-induced school closings are sure to hurt disadvantaged students the most. There’s already media accounts suggesting that low-income students are struggling to keep up in remote learning environments. Similar concerns about special-education students have also surfaced. While the state already provides more aid to high-poverty districts, it should strive for even more effective targeting of funds to help prevent disadvantaged students from falling hopelessly behind. In the next biennial budget, this could mean driving more state funding through “categorical” grants that deliver aid based directly on economically-disadvantaged, special-education, and English-language-learner enrollments. As discussed elsewhere in this piece, it might also entail an additional funding stream based on students identified as poor via direct-certification methods.

Third, concentrate on restarting the school funding formula.

For FYs 2020 and 2021, legislators suspended the funding formula, the mechanism that usually allocates state funds to school districts. Instead, districts’ current state aid is generally equal to the amount received in FY 2019 (calculated via formula based on their enrollments and state share indexes for that year).[1] Depending on whom you ask, this freeze was either enacted to buy the legislature time to continue exploring alternative funding models (like the Cupp-Patterson plan) or to give the then newly elected DeWine administration time to craft a thoughtful school funding plan. The problem, however, with keeping the formula frozen in time is that districts aren’t funded based on the students currently enrolled in their schools. For instance, a district educating twenty-five more special education pupils in FY 2022 (relative to FY 2019) won’t receive the extra dollars to support the needs of those additional students. (Conversely, this also “overfunds” a district that has fewer special education students.) At a more general level, the freeze shortchanges districts with increasing enrollments overall and/or those that are becoming relatively poorer and need more state help. In sum, getting Ohio back to a formula-based system will be critical to delivering limited resources to where they’re most needed.

Fourth, provide flexibility around how schools may spend funds.

Ohio districts and charters already have flexibility in determining how most state dollars are spent. However, the state does limit how they spend two sizeable pots of money: economically disadvantaged and student wellness funds, which together constitute about $750 million in state outlays in FY 2020. Economically disadvantaged funding must be spent on things like extended school days, community learning centers, professional development, or academic interventions. Similarly, schools must spend wellness dollars on initiatives such as mental health services, mentoring, or family engagement. Of course, these are well-meaning and potentially high-impact activities. Yet they also limit options, especially problematic if districts need to address budget shortfalls. A district, for example, might prefer to spend $200,000 in economically-disadvantaged or student-wellness funds to avoid teacher layoffs instead of supporting an afterschool program. Because those dollars are restricted, however, it would end up spending funds on a lesser priority. To give school leaders more flexibility, lawmakers could simply add provisions permitting the use of these funds for staff retention and compensation initiatives.

***

The past month has been heart-wrenching, and these trying times are likely to persist as the economy tries to regain its footing. For state and district leaders, this will mean tough budget decisions ahead. But if policymakers can maintain a focus on leveraging existing dollars to meet the needs of students, we may look back on this time as Ohio’s finest hour.

[1] The freeze doesn’t apply to charters whose FY 2020 funding is based on FY 2020 enrollments.

On March 27, President Trump signed into law the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act, or CARES Act. The bill provides $2 trillion in relief and stimulus funds for individual citizens, businesses, and organizations that have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The CARES Act addresses two issues in K–12 education. First, it gives the U.S. secretary of education the power to grant waivers to states regarding policies such as testing and accountability. Second, it provides billions of dollars to help support schools. This blog examines each in turn.

Flexibility through waivers

In the education sector, waivers that excuse states from following certain federal regulations are nothing new. Like their predecessors, the waivers offered by the CARES Act are significant though temporary. They’re also designed to be fast-tracked. The bill requires the secretary to create an “expedited” application process that approves or rejects requests within thirty days of states submitting them.

The most widely-discussed provision allows states to apply for a waiver for the 2019–20 school year that excuses them from federal requirements related to annual assessments, accountability, and report cards. The impacts of this flexibility are wide-ranging. Schools won’t be required to administer annual assessments, though states may still choose to administer them for informational purposes. Requirements for reporting progress on achievement goals, high school graduation rates, and the academic performance and growth of certain subgroups of students would be waived as well. School intervention efforts are also on pause. Schools that have previously been identified as comprehensive support or targeted support schools will remain in improvement status for the 2020–21 school year, but no new schools will be identified.

This flexibility around testing, accountability, and intervention shouldn’t come as a surprise. As early as March 12, Secretary DeVos announced that the department would consider targeted one-year waivers of assessment requirements. After an avalanche of school closures, the administration announced it planned to officially cancel the requirement for state testing this year. The CARES Act merely codifies this intention into law. Ohio has already passed legislation waiving state exams for the year, and, like all states, it already received a waiver for all federally mandated testing for spring 2020. There is still a possibility that districts could choose to administer tests whenever students return to school. But these tests won’t be high-stakes and would be used for informational purposes only. As for federally required interventions, there are 285 Ohio schools currently identified as priority (or using federal language, comprehensive support) and 537 identified as focus (targeted support). These schools will continue to receive support next year in accordance with the intervention plans they already have in place, but no new action will occur.

Relief funding

Approximately $30 billion of the $2 trillion stimulus package has been reserved for schools through the education stabilization fund. The bulk of the $30 billion is divided into three parts: an overall education relief fund reserved for governors, a pool of money for elementary and secondary education, and a separate pool for higher education.

To access these dollars, states and local education agencies (LEAs) must provide assurances that they will maintain education funding for fiscal years 2021 and 2022 at approximately the same average as the three years prior. They must also “to the greatest extent practicable” continue to pay employees and contractors during closures.

Here’s a closer look at the two pots of money available for the K–12 sector in Ohio.

The governor’s emergency education relief fund

This fund makes up almost 10 percent of the total stabilization fund and amounts to approximately $3 billion dollars. States must apply to the department to obtain a portion of the funds, and money is awarded based on two measures: 60 percent is based on a state’s relative population of citizens aged five to twenty-four, and the remaining 40 percent is based on the relative number of children ages five to seventeen who are living in poverty. The Congressional Research Service has estimated that Ohio should expect to receive around $105 million.

As its name suggests, these funds are spent at the discretion of state governors. The bill outlines three ways that governors can spend this money. They include:

It would be shocking if Ohio didn’t apply for these funds, though there’s no way of knowing how Governor DeWine will choose to spend them when they arrive. Given how often the governor discussed the importance of early childhood education while on the campaign trail, as well as the outsized importance of childcare centers during this pandemic, it wouldn’t be unreasonable to speculate that he’ll look to fund early childhood programs and centers. DeWine has also been a stalwart champion of high-poverty districts and schools. Students in these buildings will likely be the most negatively impacted by long-term closures and the abrupt shift to remote learning, so it’s reasonable to assume they’ll receive much higher funding amounts than their more affluent peers.

The elementary and secondary school emergency relief fund

This pool of money makes up nearly 44 percent of the total education stabilization fund and equals over $13 billion dollars. Like the governor’s fund, states must apply to receive money. But unlike the governor’s fund, these dollars will be allocated to states in the same proportion as Title I funding from the most recent fiscal year. Based on the available stimulus and Ohio’s most recent Title I funding allocations, it’s estimated that Ohio will receive around $489 million.

At least 90 percent of Ohio’s awarded funds must be provided to school districts and charter schools. The act lists twelve allowable uses for them, but here are a few of the most significant:

Again, it’s hard to predict which of these options Ohio leaders will choose to focus on. It will be tempting to merely spread the money around so districts can cover general operating costs. But focusing on the immediate needs of kids, not organizations, should be paramount. The governor recently extended school closures to May 1. Plenty of districts have already transitioned or are planning to transition to online learning during this time period. Despite a plethora of distance learning opportunities, thousands of students won’t be able to participate because they lack internet access or internet-enabled devices. Even if our new normal of distance learning miraculously comes to an end in the fall, and the need for such access and devices disappears, we cannot ignore the present needs of students who are being denied the same educational opportunities as their wealthier peers. State leaders would be wise to use the influx of federal funds to address these gaps. They should also consider whether summer school, either in classrooms or online, could mitigate the learning losses expected from long-term closures.

***

With at least another month of school closures ahead of us, it will be important for school leaders, educators, students, and their families to continue adjusting and adapting to our state’s new normal. The flexibilities and funding provided by the CARES Act should aid in these transitions.

It’s no secret that school choice remains a politically charged issue. Opponents urge policymakers to restrict choice and preserve the status quo, while supporters insist on parents’ right to choose a school that fits their kids’ needs. But outside of Statehouse circles, what do everyday Ohioans think about school choice? Is it as controversial as these tense political debates suggest?

Public opinion surveys usually find strong support for school choice policies. The national EdNext/PEPG survey, for example, reveals solid support for vouchers and charters, especially among African American and Hispanic respondents, and it also finds that private-school parents report the most satisfaction with their schools. A national Associated Press/NORC survey from 2017 finds much greater support for expanding charter schools than opposition. And closer to home, a recent survey of African American adults conducted by the Ohio Legislative Black Caucus Foundation and the University of Akron finds that three in five respondents support policies that provide taxpayer funding for charter and private schools.

A new survey from School Choice Ohio (SCO) and EdChoice (formerly the Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice) further reinforces these positive findings. This survey gauges Ohioans’ opinions about choice initiatives such as private-school scholarships and public charter schools. SCO is a nonprofit group that informs families about their education options and advocates for choice-friendly policies here in the Buckeye State, while EdChoice is a national organization based in Indianapolis that focuses on school choice. The online survey, conducted by Braun Research, was fielded in February 2020, garnering responses from a representative sample of 1,265 Ohio adults, good for an 18 percent response rate (above a typical phone survey).

First up, the findings about private-school scholarships, i.e., vouchers. A solid majority of Ohioans express support (69 percent), while just 31 percent oppose them. Support increases among African Americans, with 83 percent saying they favor vouchers, while 67 percent of white and Asian adults voice support, and 55 percent of Hispanics do so. Low-income respondents are more apt to say they support vouchers (72 versus 63 percent for high-income), as do people without college degrees (74 versus 61 percent for degree holders). No major differences are found by geographic region, age, or—surprisingly—party identification. When asked more specifically about support for Ohio’s two main voucher programs, similar results emerge. Seventy-four percent of Ohioans say they favor the performance-based EdChoice model and 70 percent express support for income-based EdChoice. Once again, favorable opinions for Ohio’s scholarship programs rise among African American, low-income, and non-college-educated adults.

Next, the survey gauges opinions about public charter schools and educational savings accounts (ESA). Akin to vouchers, a strong majority of respondents support charters: 65 percent say they favor charter schools, while just 35 percent oppose them. Favorable opinions increase among African Americans (74 percent) and Hispanics (79 percent), with a somewhat smaller majority of white (64 percent) and half of Asian adults voicing support for charters. The survey also finds stronger support among low-income and non-college-educated adults (72 percent for each group). Although Ohio doesn’t have an ESA program, the concept garnered strong support among respondents with 82 percent saying they’d support a program that provides public aid directly to parents who can use those funds for educational purposes.

Last, Ohio parents are asked about satisfaction with their children’s schools and the type of school to which they’d prefer to send their kids. In terms of parental satisfaction, a whopping 92 percent of private school parents say they’re satisfied with their school, with somewhat smaller majorities of charter (79 percent) and district parents (66 percent) expressing satisfaction. As for which type of school would be parents’ first choice—were there no financial or transportation considerations—56 percent choose private schools, 27 percent select district schools, 10 percent prefer charters, and 7 percent opt for homeschool. As the report authors note, these results indicate a “glaring disconnect” between school preferences and actual enrollments. While most Ohio parents say they’d prefer to enroll their child in a private school, only 11 percent actually do so.

Much of the discourse around school choice is dominated by critics with an interest in curbing educational options. Yet their views are out-of-step with the broader public—particularly of less advantaged parents—who express support for choice initiatives such as vouchers and charter schools. As the debates continue, policymakers should be mindful that the loudest voices calling for limits on school choice don’t reflect the views of most Ohioans.

Editor's Note: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

Author's Note: The School Performance Institute’s Learning to Improve blog series typically discusses issues related to building the capacity to do improvement science in schools while working on an important problem of practice. However, in the coming weeks, we’ll be sharing how the United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter management organization based in Columbus, is responding to and planning educational services for our students during the COVID-19 pandemic and school closures.

Once we at the United Schools Network learned about Governor DeWine’s school closure order on the afternoon of March 12, the pivot to remote learning began immediately. The first thing we did was create a COVID-19 Task Force to start planning for the initial three-week closure. While those plans were quickly implemented, we’ve now transitioned to creating longer term plans that address learning needs as Ohio schools will remain physically closed to May 1 and possibly beyond.

This limited (we hope) blog series is our attempt to share what we’re learning during the pandemic. We’ve outlined seven early lessons in this post, which are focused on setting a network or district up for success throughout the closure.

Lesson 1: Create a well-balanced team focused on responding to the pandemic.

The COVID-19 Task Force we created has the responsibility of guiding our network through the pandemic. It includes senior leaders from our network office in addition to school and teacher leaders from each of our four schools. It has four primary purposes: (1) communicating with staff and families; (2) designing remote learning; (3) reviewing and creating policies and procedures; and (4) coordinating support to our students, families, and staff during this challenging time.

Lesson 2: Plan for how work will happen in key areas.

We already frequently use Google Drive as our primary knowledge management tool, so it made sense to continue to do so during the pandemic. The first thing we did when we convened our task force was to create a shared drive with all task force resources. Our knowledge management system is broken down into six areas: (1) project management, (2) resources, (3) communication plan, (4) education plans, (5) HR and operations plan, and (6) talent and hiring.

We defined these six areas as the core functions that we have to get right to operate at a high level during the closure. All materials are carefully organized within these sub-folders. There is generally one task force member heading up each of these critical areas and creating network-wide operations plans.

Lesson 3: Start each team meeting with level setting.

Conditions are changing rapidly with information from local, state, and federal sources coming in at a breakneck pace. It is critical that leaders of this work are on the same page. We started our very first task force meeting with forty-five-minutes of level setting. All known information was put on a white board, and then task force members added what they knew about the closure, and also had chances to ask questions. Our twice-a-week virtual meetings start with a standing agenda item called “Update on Situation,” during which team members review and discuss state and federal policy changes since the last meeting.

Lesson 4: Establish a single point of contact for organization-wide communication.

We did this at our very first task force meeting. For us, this is our Chief Schools Officer and Co-Chair of our task force. As of March 30, she has sent six all-network emails, on March 12, 13, 15, 18, 26, and 30. These were more frequent when the original closure order was put in place because things were changing so quickly. Content typically includes an update on state and federal policy and building access parameters and a word of encouragement.

Lesson 5: Be flexible.

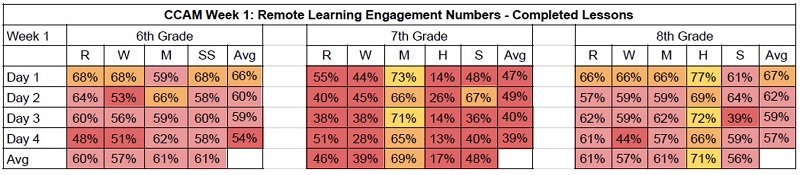

When the closure order first came in, our task force quickly worked to create a short-term education plan. However, we also gave teachers a week to experiment with various online learning platforms, such as YouTube and Google Classroom. While some teachers are more tech savvy than others, even those that were well-versed in these platforms are used to using them with students in the classroom. Similarly, students also had to adjust to this unfamiliar environment. The table below measures the percentage of students at one of our middle schools that are completing online practice related to the daily lesson that each teacher is posting.

Even though we weren’t grading assignments in the first few weeks of the closure, we have begun to collect this engagement data to see where our initial education plan is working and where it is not. At the same time, we’ve been working to coordinate efforts to ensure all 900 students in our network have a device and internet access. We’ll be able to use these early lessons, in terms of access, lesson design, and student engagement, as we formulate our long-term education plan.

Lesson 6: Check-in with your community frequently.

The health and well-being of our school community is at the front of our minds. All of our schools are meal distribution points for our neighborhoods, and teachers are checking in twice-a-week with students. Similarly, a small team from our network’s home office has divided up our staff roster, and we’re making calls this week to check in with all of our staff members. We’re asking questions like: “how are you doing?,” “do you have everything you need?,” and “do you have any questions?” It is more important than ever right now to work together as a community to take care of each other.

Lesson 7: Think about what’s next, now!

One of the toughest but most important things to do during an uncertain situation is to plan for the long-term. This is challenging when there is so much uncertainty right now. However, as educators, we need to be thinking now about how we are going to do school remotely for the foreseeable future. It is even possible that we may go back and forth between opening and closing schools for the next twelve to eighteen months until either a vaccine or treatment is developed.

We hope these seven lessons can be of use to other districts, schools, and charter networks that are making major transitions during the pandemic. Our remote learning team, which is a subset of our full task force, is working on long-term plans now, and we’ll be sharing what we’re learning in future posts. Stay tuned!

John A. Dues is the Managing Director of School Performance Institute and the Chief Learning Officer for United Schools Network, a nonprofit charter-management organization that supports four charter schools in Columbus. Send feedback to [email protected].

On March 25, Ohio lawmakers unanimously passed emergency legislation that covers an array of policies affected by the coronavirus pandemic. In the realm of K–12 education, the bill (HB 197) allows high school principals (in consultation with teachers and counselors) to determine whether seniors in the class of 2020 who haven’t yet met state requirements may receive diplomas. It also exempts schools from administering state exams for the 2019–20 school year.

Authorizing school leaders to award diplomas was likely necessary for this year. Seniors still working to meet one of the graduation pathways—whether passing state exams, earning industry credentials, or several other alternatives—have had these options removed due to the closures. Yet as principals make decisions about graduation, they should remain mindful that non-college-going students—likely a large portion of those who haven’t yet met state requirements—will be entering a suddenly rough labor market. Though surely a difficult decision, withholding diplomas to less-than-ready students and encouraging them to repeat senior year might be a better option that having them face the prospect of unemployment.

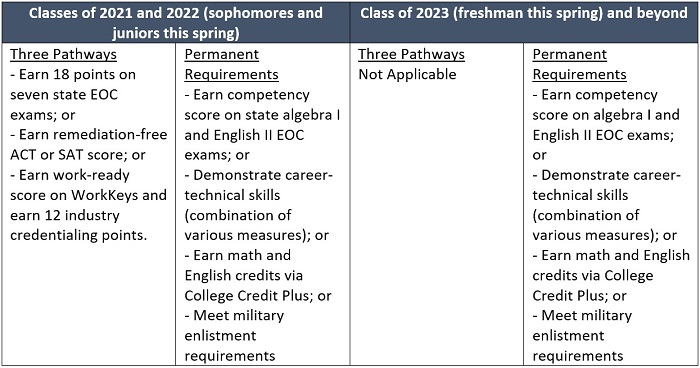

While the immediate focus may be on the class of 2020, the state testing waivers create complications for future graduating classes. The table below displays the graduation requirements for the classes of 2021 to 2023. The “three pathways” refers to the “original” options that were first implemented starting with the class of 2018, while the “permanent requirements” refers to the recently enacted criteria that modified requirements after much debate. As the table indicates, the classes of 2021 and 2022 have the option of following either the three pathways or permanent requirements criteria to earn diplomas, while the permanent requirements begin full implementation with the class of 2023.

Table 1: Overview of graduation requirements for Ohio’s classes of 2021 through 2023

Note: The graduation requirements for the class of 2020 were different—they included several other alternatives (e.g., work hours and capstone projects)—than those for the classes of 2021 and beyond. Under longstanding state policy, students must also meet course-taking requirements, and under the permanent requirements pathway need to earn at least two “diploma seals.” For more details, see Ohio Department of Education, Overview of Graduation Requirements by Graduating Class.

Two things are important to know. First, in the coming years, most high school students will rely on passing the state end-of-course exams (EOCs) to meet graduation requirements.[1] The most critical for the classes of 2021 to 2023 are algebra I and English II, because students can achieve a competency score on them and meet a key graduation requirement. Second, the EOCs are designed to be taken right after students complete the course—much like an AP calculus exam is supposed to be taken after an AP calculus course.

The problem, then, is that a large number of Ohio’s freshmen, sophomores, and juniors (and some middle schoolers, too) are presently taking courses with corresponding EOC exams. If their schools don’t administer EOCs this spring, students will miss a chance to take the test with the material fresh in mind.

How to solve this conundrum? Like most things during this crisis, there’s no easy solution. But it’s worth going back to HB 197. Crucially, the legislation does not prohibit a school from administering state exams. Rather, it excuses schools from this requirement. Therefore, schools (should they be able to reopen safely) appear to have the discretion to administer EOCs when students physically return to school.[2]

In such case, Ohio schools should consider using their authority to administer the algebra I and English II exams, if not all of the EOCs, especially if they think students have made progress via remote learning. This would give students a much better shot at passing exams than if assessment waited until next year when many will have moved onto other courses. It would also enable schools to know sooner which students need help passing EOCs moving forward (retakes are allowed). At the very least, schools should offer EOCs to any student requesting to take an exam.[3]

Of course, it may not be safe to reopen schools before the school year ends. But even then, there are possibilities: Could schools open their doors over the summer to allow students to take EOCs in a specified window? Could they administer exams as soon as school restarts in the fall, or perhaps after some remediation? Could the Ohio Department of Education work with the EOC test developer to provide an at-home testing option without compromising the integrity of the assessment? (The College Board is working on this for AP exams.) Whatever the case may be, the state and local schools should strive to offer students the opportunity to take the EOCs as close to the completion of a course as possible.

In this extraordinary hour, legislators have temporarily suspended a number of policies that govern life during normal times. Now—more than ever—state and local leaders need to exercise their powers to act in the best interests of students.

[1] There are currently seven EOCs: English I and II; algebra I and geometry (or integrated math I and II); U.S. history, U.S. government, and biology. Starting with the class of 2023, the geometry and English I EOCs will be eliminated.

[2] The state superintendent may need to waive provisions related to testing windows; HB 197 provides him with broad authority to waive or extend deadlines during the health crisis.

[3] HB 197 cancels school report cards for 2019–20, so schools would not be held accountable for the test results.

The vast majority of voucher program studies have shown positive competitive effects, meaning that students who remain in public schools benefit as their schools are exposed to competition from private-school-choice programs. The latest working paper from David Figlio, Cassandra Hart, and Krzysztof Karbownik adds to the literature by examining one of the nation’s oldest and most expansive of these programs, the Florida Tax Credit Scholarship (FTCS). Its long history and rich data make it possible for the authors to provide more evidence of positive competitive effects and to attempt to define and describe the mechanisms behind competitive pressure.

Figlio and team merge student-level school records with state birth records and use a student fixed effect design to explore impacts of competitive pressure on public school students’ educational (test scores) and behavioral (absenteeism and suspensions) outcomes. The sample size is large—nearly 1.2 million students in Florida public schools between 2002 and 2017—but also limited in a few important ways. It includes only students in grades three through eight (to take advantage of consistent testing data conducted in those grades) and who were also born in Florida and attended public schools consistently throughout this time period. Students with severe disabilities were excluded. Despite this, nearly 81 percent of children in the birth record data are ultimately represented in the school data.

Consistent with the majority of previous studies, the analysts find that the FTCS program produced statistically significant benefits for students whose public schools were exposed to increasing competition from private schools. The greater the exposure, the greater the benefits. To measure the level of exposure, the analysts have developed a competitive pressure index that combines five elements of the private school landscape within a five-mile radius of any given public school: the number of private schools serving the same grade range, the distance between each public and private school, the diversity of private school types (Catholic, Lutheran, non-denominational, secular, etc.), the number of seats in those private schools, and the number of churches. It is through this mechanism, and a couple of other nuances of the research design, that they are able to isolate the effects of competition. And by varying the weights of the components, Figlio and team find that private school density appears to be the main driver of competitive pressure. In other words, benefits observed are modestly larger for students attending public schools that have more extant private competitors nearby prior to the expansion of the program. This is a new wrinkle in the competitive effects literature and deserves to be explored more fully.

Observed benefits overall include higher standardized test scores (a 10 percent increase in FTCS participation is associated with a 0.4 percent of a standard deviation greater improvement in public school students’ math and reading scores) and lower absenteeism and suspension rates among public school students. The former declines by 0.5 percent and the latter by 0.4 percent. Effects are particularly pronounced for lower-income public school students, as per previous research, but are also positive for more affluent children. While these seem like modest effects when rendered in this way, they are seen over a huge number of students and over a fifteen-year time span. That adds up to significant benefits for kids. Additionally, the widespread nature of the benefits indicates that generalized school improvements, rather than those targeted solely at scholarship-eligible students, explain the results. (For a more thorough discussion of the observed effects and the researchers’ efforts to isolate them, please check out the Education Gadfly Show podcast from February 26.)

Private-school competition, as research continues to show, improves education generally. Defining what effective “competition” really consists of in the non-market education space—and figuring out how policymakers can leverage that knowledge to benefit kids—could be a game-changer in raising the bar for all students.

SOURCE: David Figlio, Cassandra Hart, and Krzysztof Karbownik, “Effects of Scaling Up Private School Choice Programs on Public School Students,” Northwestern Institute for Policy Research Working Papers (February 2020).

Work-based learning (WBL) refers to career preparation and training that occurs within a job setting, connects to classroom and academic experiences, and involves supervision and mentoring. Recent federal efforts like the Community College Apprenticeships initiative and state-driven programs like Pathways in Delaware have increased awareness of WBL and solidified it as a critical method for preparing students for high-wage, high-demand jobs. In general, there are four main models: apprenticeships, internships, cooperative education (co-ops), and practica and clinical experiences.

Despite recent expansion efforts, WBL programs in most places still lack clear frameworks for measuring student participation and outcomes. A new report from the Urban Institute sheds some much needed light on the WBL landscape and on-the-ground implementation efforts. The analysis focuses on community colleges, as they enroll millions of students in credit-bearing courses and noncredit workforce programs, have diverse student populations, and provide career-focused degree and certificate programs that require close collaboration with employers.

To understand the broader WBL picture, the authors examined existing research and national data sources such as the Adult Training and Education Survey and the Registered Apprenticeship Partners Information System. They also conducted interviews with national experts and state agencies. Overall, the data indicate that WBL opportunities are growing in number. Unfortunately, data also indicate that disparities in access, participation, and outcomes exist across WBL models for traditionally underrepresented groups such as women and people of color.

At the community college level, there are very few nationally representative data sources that focus on WBL. Research on outcomes—such as persistence toward degrees and certifications, post-WBL employment outcomes, retention rates, and wages—is limited. Registered apprenticeships have a stronger evidence base because they are tracked by the federal government. Results show that enrollees have higher earnings. In the ninth year after program enrollment, they earned on average almost $6,000 more a year than they would have if they hadn’t participated in an apprenticeship. Results for co-op programs, which alternate classroom learning with learning on the job, are varied. Some studies show they lead to impacts such as reduced time to finding employment and higher starting salaries, while others suggest these impacts fade over time. Internships, meanwhile, have very little research associated with their impact despite being extremely popular. One study found that longer-term, paid internship programs were associated with better outcomes than short-term, unpaid programs.

To better understand how WBL works on the ground, the authors interviewed representatives from six community colleges about their experiences implementing and measuring it. By and large, these schools offer WBL on a continuum that ranges from low-involvement career awareness activities to more intensive programs aimed at career preparation and training. Opportunities are usually linked to college credit and academic or instructional components. For example, one college offers an online WBL course that requires students to submit writing assignments throughout their experience. Several colleges have dedicated staff, such as a WBL coordinator, who is responsible for managing relationships with employers.

In terms of implementation, a persistent concern for all respondents was the structure of WBL for students who have full- and part-time jobs. If a student’s job is related to their program of study, colleges reported that they attempted to make accommodations to align the job with WBL recognized by the college. When that wasn’t possible, they attempted to be flexible in other ways, such as allowing students to complete their WBL experience over a longer period of time.

Unfortunately, gathering employment and outcome data seems to be mostly aspirational for these colleges. Some are able to access state wage records, but others are limited by privacy laws and other roadblocks. They typically rely on course codes to track how many students participate in WBL each semester. Tracking WBL outside of course credits is far more difficult, though many colleges are actively working to improve their data collection efforts. Colleges also rely on student and employer feedback surveys to gauge program quality and outcomes. Low response rates and survey fatigue among both students and employers was cited as a challenge to obtaining consistent data from these efforts. Nearly all respondents mentioned that limited funding is a serious barrier to robust data collection.

The report closes with recommendations. Both federal and state governments should develop a common definition of WBL and identify data elements that should be tracked. States would be wise to incorporate WBL into their longitudinal data systems. Community colleges should consider incentivizing employers and students to complete surveys to get consistent and reliable data. And philanthropies should provide funding that can build capacity among government agencies, colleges, and employers to help track outcomes. Overall, identifying strategies to assess participation, progress toward diversity and equity goals, and outcomes is vitally important.

Source: Shayne Spaulding, Ian Hecker, Emily Bramhall, “Expanding and Improving Work-Based Learning in Community Colleges,” Urban Institute (March 2020).