Has Ohio public school enrollment declined amid the pandemic?

Here’s how Ohio could make summer school available to all students who need extra help

A deep dive into Ohio’s fund for high-quality charter schools

Ohio is making strides in education data transparency—but there’s still work to do

Ohio should rely on direct certification to identify and fund poor students

Here’s how Ohio could make summer school available to all students who need extra help

A deep dive into Ohio’s fund for high-quality charter schools

Ohio is making strides in education data transparency—but there’s still work to do

Ohio should rely on direct certification to identify and fund poor students

Open Enrollment and Student Diversity in Ohio’s Schools

Has Ohio public school enrollment declined amid the pandemic?

A slew of news stories from around the nation have reported declining K–12 public school enrollments amid the pandemic. Given the disruptions and uncertainties, this slippage isn’t surprising. More parents may be choosing homeschooling, private, or full-time online schools over their assigned district option. Various reports cite lower kindergarten enrollments, as parents “redshirt” their children this year. The slide might also reflect more students disengaging from their education and dropping out.

Have enrollment patterns in Ohio followed the national trajectory? While a few stories have appeared in Ohio media on kindergarten, e-school, and local patterns, no one has yet to offer a more complete picture of enrollment for the 2020–21 school year. To fill the void, this piece takes a look at the year-to-year enrollment changes across Ohio’s 600-plus school districts and roughly 300 public charter schools. The analysis that follows examines four key questions about enrollment this year and concludes with some thoughts on policy implications.

Question 1: Have traditional school district enrollments fallen this year?

Based on headcounts reported via the Ohio Department of Education’s (ODE) school finance datasets, district enrollment is down by 2.8 percent this year versus the year prior. In December 2020, the state reported 1,501,647 students in traditional districts; one year later, that number has fallen to 1,459,901 students—a decrease of 41,746. District enrollments had been on the decline before Covid-19—falling by an average of 0.4 percent per year from 2016–17 to 2018–19. But the 2.8 percent loss is higher than usual, suggesting the dip is mostly linked to pandemic-related issues, some of which we’ll discuss below.

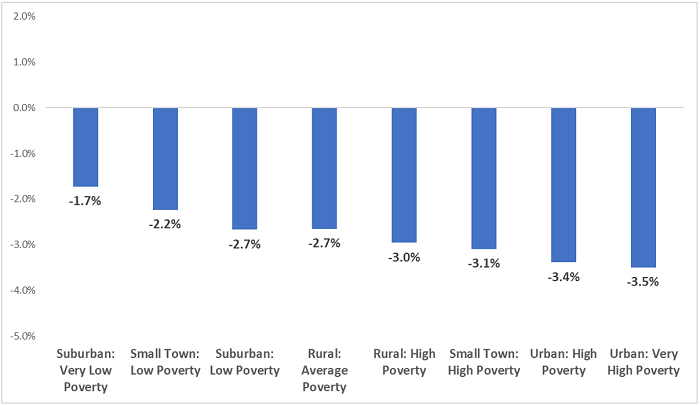

Figure 1 displays the enrollment data by district typology, a method of grouping districts with similar geographic and socioeconomic characteristics. The higher poverty typologies—whether rural, small town, or urban—experienced declines of more than 3 percent, while the lower-poverty typologies registered smaller losses. We don’t know for sure why poverty would matter, but potential explanations include fewer school reopenings in high-poverty areas (especially big cities), lower rates of kindergarten enrollment, or more students that have gone missing.

Figure 1: Change in enrollment by district typology, December 2019 versus December 2020

Source: Ohio Department of Education, District Payment Reports (FY 2021, December #2 Payment File) and District Typology.

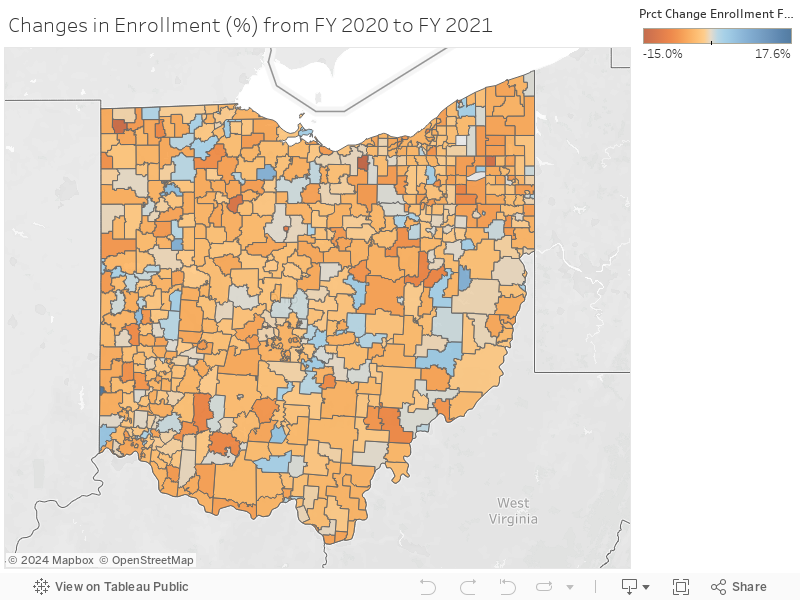

The enrollment changes vary widely across Ohio districts. Eighty-two systems, in fact, reported increased enrollments this year—the biggest gainer being College Corner, an unusual jurisdiction that spans Indiana and Ohio (up 18 percent). The steepest decline was observed in Oberlin (down 15 percent). To view data from all Ohio districts, click on the map here or displayed at the bottom of the webpage.

Question 2: Are enrollment declines associated with reopening decisions?

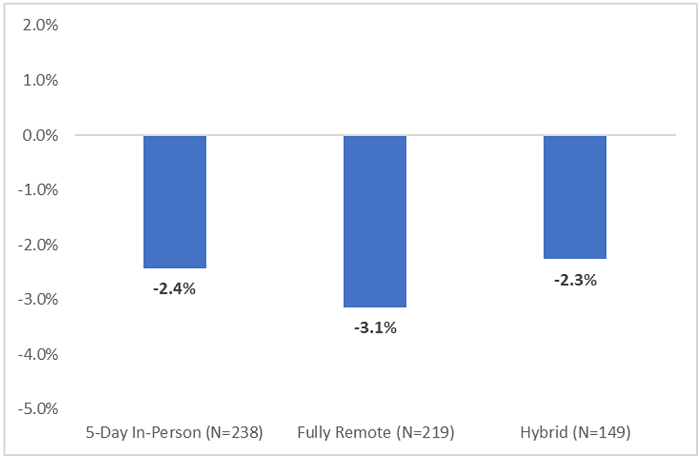

The chart below indicates that remote-only districts have experienced somewhat larger dips compared to those that offered an in-person option. The average year-to-year loss among fully-remote districts was 3.1 percent versus 2.4 and 2.3 percent for in-person and hybrid districts, respectively. The larger declines might be due to more parents seeking other alternatives when their district announced a remote-only policy, or perhaps higher rates of redshirting or dropout when online learning is the only educational option.

Figure 2: Change in district enrollment by instructional model, December 2019 versus December 2020

Source: ODE, Educational Delivery Model for 2020-21 (week of January 4, 2021). ODE regularly updates reopening information; thus, data from the start of the 2020–21 school year are not presently available.

Question 3: Are lower kindergarten enrollments contributing to losses?

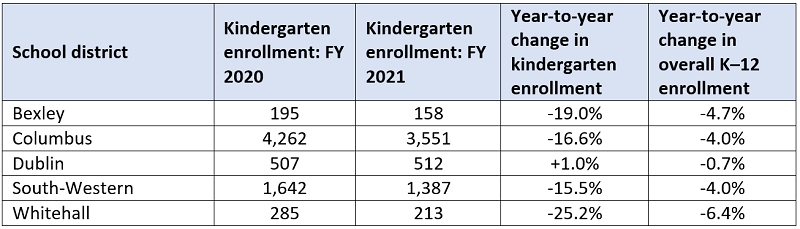

Lower kindergarten headcounts are almost surely factoring into the declines, but it’s hard to determine the extent to which they’re contributing. There is no straightforward way of calculating statewide enrollments by grade level via the school finance datasets. However, a look at a few district’s funding data does show a dip in kindergarten enrollment. Table 1 shows the pattern using several Franklin County districts of various demographics selected for illustration. Four of the five districts experienced rather large decreases in kindergarten enrollment, with just one district (Dublin) posting a slight uptick.

Table 1: Kindergarten enrollment in selected Ohio districts, December 2019 versus December 2020

Question 4: Are public charter school enrollments also falling?

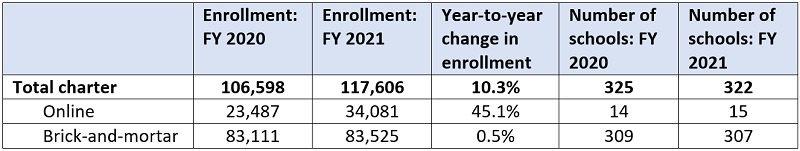

As table 2 reveals, charter enrollments—e-school and brick-and-mortar combined—rose by 10 percent relative to 2019–20 headcounts. The growth is almost entirely due to online charters whose enrollments are up by more than 10,000 students this year, surely reflecting a growing interest in online options among Ohio parents. Interestingly, brick-and-mortar charters—most of which are high-poverty, urban schools—are faring better than their district counterparts in terms of maintaining enrollments. It’s not clear why that is, but perhaps they are better satisfying parents and engaging students amid the pandemic.

Table 2: Public charter school enrollment, December 2019 versus December 2020

Source: ODE, Community School Payment Reports (FY 2020 and 2021 December Payment File)

***

Will these K–12 enrollment trends persist or are they fleeting? Like all things pandemic related, no one knows what’ll happen next. Despite the uncertainties, policymakers should consider two implications of these data:

Return to state funding policies that base allocations on current-year enrollments. In July 2019, long before Covid-19 had emerged, legislators suspended the formula used to allocate state funds to traditional districts, choosing instead to fund districts based on FY 2019 headcounts. (Legislators were debating the formula at the time but couldn’t agree on a new one.) Though obviously not related to the crisis that followed, this policy has to some extent shielded districts from funding reductions associated with pandemic-driven enrollment declines. However, given the possibility of further enrollment shifts moving forward, it’s especially important for the state to return to a policy of funding districts based on current-year enrollments, as it had done before the freeze.

Such a “funds follow students” model is fair to children, helping to ensure that they receive appropriate resources for their education. It’s also fair to the schools that bear the responsibility of serving them and it represents good stewardship of state dollars, refusing to fund “phantom students” who are no longer enrolled in a particular district or school. Last, in the context of school reopenings, funding based on current enrollments could discourage the continuing use of remote learning—a model that parents are less satisfied with and isn’t ideal for most students—in the fall of 2021, as it would put districts’ funds at risk if students opt for in-person alternatives.

Get ready for larger kindergarten classes next year. With lower numbers this year, state and local leaders should begin preparing for larger kindergarten class sizes in 2021–22. At a state level, policymakers may need to consider regulatory flexibilities that allow schools to address larger-than-usual kindergarten cohorts. At a local level, it might mean strategically reconfiguring space, redeploying staff, increasing learning time, or even adding a grade level to address student needs in the coming years.

These enrollment data only offer a glimpse of K–12 education during the pandemic. They don’t tell us about whether enrolled students are participating in learning opportunities (“in attendance”), mastering academic content, or feeling physically and emotionally well. What they do indicate is that things have changed, at least temporarily—and perhaps more permanently into the future.

Here’s how Ohio could make summer school available to all students who need extra help

It’s no secret that the school closures and remote learning efforts brought about by Covid-19 may be causing a significant amount of student learning loss. To mitigate these losses, leaders at the state, local, and school level will need to get creative.

In Tennessee, state policymakers have already risen to the challenge. The General Assembly recently passed the Tennessee Learning Loss Remediation and Student Acceleration Act, which requires districts and schools to implement three extended learning programs—referred to as “camps”—designed to catch kids up on what they missed.

The three camps share the same underlying purpose but differ on the details. After-school learning mini-camps will provide STEAM learning opportunities to students. Learning loss bridge camps will be four-week programs that occur annually prior to the start of a new school year. Summer learning camps, meanwhile, will be intensive six-week programs that occur during the summer months.

Ohio should follow Tennessee’s lead and implement similar initiatives. Despite a struggling economy, we have the money to do so. The federal Covid-19 relief package signed into law in December will send a whopping $2 billion to the Buckeye State. The vast majority of these dollars will be distributed directly to schools, of course, but the law allows state departments of education to set aside 10 percent of their allocated funds for discretionary purposes. In Ohio, that equates to approximately $200 million.

Ohio should use this funding—and other sources, such as the $46 million available through the Governor’s Emergency Education Relief fund included in the same relief package—to implement a statewide summer school program this coming summer. But how would such a program work? Here’s a look at key features of Tennessee’s efforts, and how they should help shape Ohio’s approach.

Student eligibility

In an ideal world, every student who wanted access to summer programming would have it. In the real world, though, funding and staffing are limited. To address potential limitations, Tennessee’s proposal requires schools to offer their seats to priority students first. The definition of a priority student varies based on the camp (remember, there are three). But in general, priority students are those who are entering certain grades, scored below proficient on the most recent math or reading state exam, attend schools where a majority of students did not score proficient, or are eligible for the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program.

Ohio would be wise to model its own eligibility guidelines on these parameters while operating within Ohio’s specific context. For example, the Buckeye State could identify students as eligible for summer school if they meet at least one of the following conditions:

- Students who scored below proficient on either the reading or math Ohio State Test during the 2018–19 school year.

- Students who are considered economically disadvantaged. This could include students who are eligible for TANF or SNAP assistance.

- Students who attend a building identified as either a priority or focus school during the 2018–19 school year.

Ohio should also ensure that eligible families who exercise school choice have equal access to summer school options. Tennessee’s legislation explicitly requires districts to provide enrollment opportunities to all priority students, even if they aren’t enrolled in the district. That means priority students who are enrolled in a charter school located within the geographic boundaries of the district must be given an opportunity to enroll in that district’s program. The bill also allows public charter schools to conduct their own camps rather than sending their students to the district. Ohio should follow suit in both regards.

Ohio lawmakers should also extend the guidelines to include private school students who meet the aforementioned eligibility criteria and live within the boundaries of the district. Given that the state is picking up the entirety of the tab, one would hope that such a move wouldn’t draw too much ire from the education establishment. In this instance, where students choose to attend school shouldn’t matter. All that should matter is using the influx of federal dollars to remediate the learning loss of as many Ohio children as possible.

Data and transparency

Summer school staff in Tennessee will be required to administer a state-approved benchmark assessment to students at the beginning and end of the program. These results must be submitted to the state department of education to gauge how successful the camps have been at catching students up.

Ohio should do the same, but should take it one step farther and publish the results. To be clear, these test results should not be tied to the state accountability system or consequences of any sort. State leaders should also be careful to protect student privacy, especially when breaking down the data by subgroup. But being transparent with the results is important and will help state and local leaders identify quality summer programs that could be replicated elsewhere in the years ahead.

Staffing

Tennessee’s proposal includes two provisions aimed at teachers and staff. First, it requires that stipends be paid to the teachers, tutors, and staff providing services at camps. This seems like a no-brainer, but it’s important to explicitly include in law so that districts don’t attempt to cut costs by requiring teachers to work over the summer as part of their contractual obligations. Second, the legislation requires Tennessee’s Department of Education to create and administer a preparation course that will train and certify adults who don’t have a teaching license to provide instruction. This is crucial because it addresses potential staff shortages. Obviously, it’s critically important that students interact with high-quality, experienced teachers as much as possible. But there are only so many of those to go around, and now is clearly the time for a “all hands on deck” mentality. By following Tennessee’s lead in this regard, Ohio can ensure that schools are able to leverage community members, parents, and other adults who are ready and eager to help.

Time and content

Tennessee’s legislation offers specific guidelines for how extended learning time should be spent. Their proposed summer camp, for instance, is required to last six weeks. Each day must include at least four hours of in-person instruction in math and reading, one hour of response to intervention services in those same subjects, and an hour of physical activity.

In general, these are solid guidelines. Ohio should be similarly specific about how students spend their time while enrolled in summer school. But Ohio leaders might also consider requiring schools to spend an hour of their in-person instruction each day on additional content areas, such as social studies or science. Math and reading are unquestionably important, particularly in light of substantial learning loss, but research shows that a knowledge-rich curriculum improves academic growth and achievement. Expanding the scope of instruction to include other content areas would be wise.

***

As Ohio gears up for a busy budget season, it’s important that leaders not forget about the state’s recent influx of federal relief funding. There are plenty of initiatives worthy of investment, but none would be quite as impactful as offering extended learning time this summer to a significant number of Ohio students. Hopefully, since summer will be here before we know it, an effort like this will be fast-tracked and enacted quickly into law.

A deep dive into Ohio’s fund for high-quality charter schools

Two years ago, Governor DeWine and the General Assembly enacted a bold initiative that boosts funding for quality public charter schools. The Quality Community School Support Fund provides eligible charters up to an extra $1,750 per economically disadvantaged (ED) student and $1,000 per non-disadvantaged pupil. To tap this $30 million per year allocation, a charter school had to meet certain performance-based criteria (discussed more below). These supplemental dollars narrow the sizeable funding gaps that exist between Ohio’s urban charters and districts, and they help successful charter schools build the capacity to serve more Ohio students.

With two years in the books—and reauthorization looming in the upcoming budget—it’s time to take a closer look at how the program has worked thus far. The analysis below first offers a big-picture snapshot of the program in its first two years of existence. Then it takes a closer look at the newly qualifying schools in year two, as some may wonder whether those schools were worthy additions. Last, it considers how the program might be fine-tuned moving forward.

Basic overview

To receive supplemental funds, a charter school must achieve one of three conditions. In general, the criteria are as follows:

- Criteria 1: The school posts a performance index score higher than its local district for the past two years and achieves an A or B rating on the state’s value-added measure in the most recent year. Report card results from 2016–17 and 2017–18 were used to determine the first round of qualifying charters (FY 2020), while 2017–18 and 2018–19 results determined the second round (FY 2021).

- Criteria 2: The school is in its first year of operation and is modeled after a school that meets the criteria 1 conditions.

- Criteria 3: The school is in its first year of operation and is managed by an out-of-state operator that meets certain conditions.[1]

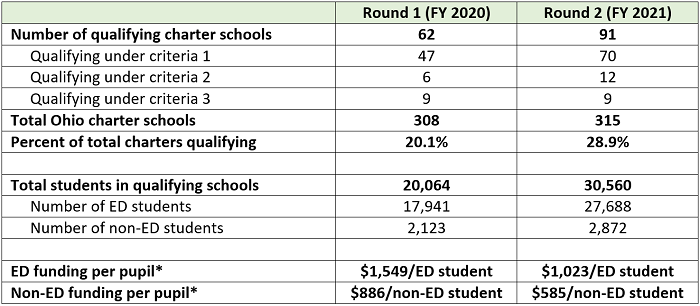

The table below offers an overview of how many Ohio charter schools met these criteria in the first two years of funding.

Table 1: Ohio’s Quality Community School Support Fund, FY 2020 and 2021

Source: Ohio Department of Education. *To fit the $30 million per year appropriation, the “base” ED and non-ED amounts ($1,750 and $1,000 per student, respectively) were multiplied by 88.57 percent in FY 2020 and by 58.45 percent in FY 2021 to yield the actual amounts that qualifying schools received.

Four observations:

- Overall, the program parameters appear to be reasonably stringent, with 20 percent of Ohio charters qualifying in year one and 29 percent in year two.

- The number of qualifying charters rose quite significantly from the first to second year—from sixty-two to ninety-one schools. It must be noted that schools retain their “quality” status for two years after initial designation. Thus, notwithstanding a school closure, the list could only have expanded in year two.

- Consistent with the expanding list, we also see a jump in the number of students who attend qualifying charters. In the first year of the program, the extra funds supported just over 20,000 students who are overwhelmingly economically disadvantaged. That number rose to more than 30,000 in the second year.

- The rise in the students enrolled in qualifying schools led to a noticeable decline in the per-pupil allotments. Due to the limited funding pool, the program was able to only provide an extra $1,023 per economically disadvantaged pupil in FY 2021.

Newly eligible schools in year two

As the table above indicates, a somewhat surprising number of new schools qualified for the second round of funding. What do we know about these schools? Did they make noticeable improvements to achieve the quality designation?

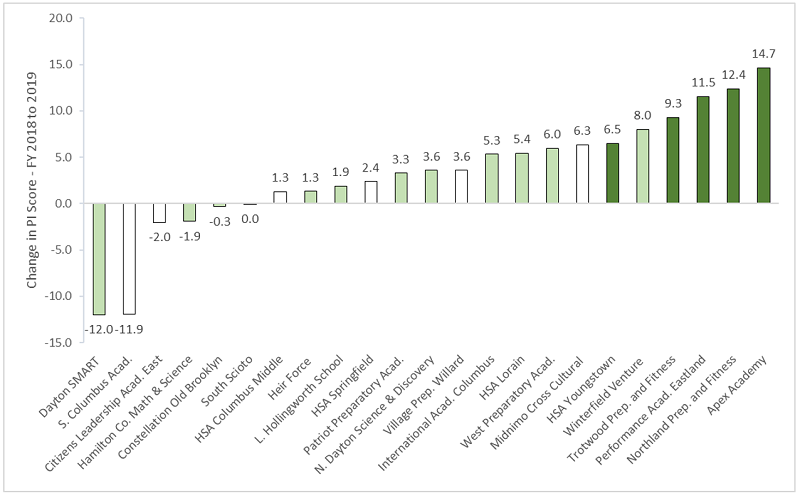

The figure below displays the year-to-year changes in the performance index (PI) scores and value-added ratings of the twenty-three additional schools qualifying under criteria 1.[2] Encouragingly, a large majority of these charters posted improvements in their PI scores. In fact, the average increase among these schools was 4.1 points, well above the statewide increase of just 0.5 points, and most of the newly qualifying schools also received higher value-added ratings. It’s true that a few schools registered lower PI scores. In a couple cases, however, the school posted high PI scores (despite the one-year decline) and solid value-added ratings, but was simply ineligible for the first year of funding because it lacked 2016–17 PI scores. On the whole, we see that the large majority of the newly qualifying schools improved on two important dimensions of performance, enabling them to join the program in the second year.

Figure 1: Year-to-year changes in performance index scores and value-added ratings of schools first receiving quality charter funding in FY 2021

Note: The color of the bar indicates the schools’ change in value-added ratings from 2017–18 to 2018–19. An empty bar indicates no change in value-added rating, a light green bar indicates an improvement of one or two letter grades, and a dark green bar indicates an improvement of three or four letter grades.

Looking ahead: Make the program permanent

Hats off to lawmakers for establishing this funding program that serves important purposes. While it’s premature to evaluate whether the program has achieved all its goals, it’s definitely on the right track. Many well-deserving charters are now receiving extra dollars that allow them build on their successes and serve more Ohio students.

Yet as currently designed, the major limitation of the program is a funding structure that causes per-pupil allocations to fall when more schools are identified. In the next round of funding, that should change. Legislators have a few options to address this specific problem. Among the more temporary alternatives, they could either: (1) increase the line-item appropriation from $30 million per year to an amount that better aligns per-pupil funding with the number of charters likely to qualify in the next biennium,[3] or (2) slightly raise the performance bar in an effort to concentrate funding on the very best charters.

More ideally, however, lawmakers would cement the program into permanent charter school funding law, thus ensuring that the funds are drawn from the main K–12 education appropriation. Rather than funding the program via a separate line item in the state budget with temporary appropriation language, this option would treat the high-performing supplement like the other components of the charter funding formula (e.g., akin to the extra funding schools generate based on special-education enrollments). Importantly also, this could and should be directly funded by the state and not result in larger deductions from school districts. Overall, this option would ensure that qualifying charters receive the full per-pupil amounts called for under the program, protect the funding from politically-driven reductions or a line-item veto, and give charters more budgetary certainty moving forward. This type of permanency and fiscal certainty is especially crucial for successful charters seeking to open new schools in Ohio—one of the central goals of the program.

As a recent evaluation shows, Buckeye charter schools are making positive impacts on thousands of Ohio students. The schools that have qualified for this supplemental funding are almost surely the ones that are driving these gains. To keep the momentum going, state legislators should proudly reauthorize this valuable program and make it permanent.

[1] Though unintended, nine longstanding, Ohio charter schools qualified under this criteria in the first round of funding based on their operators’ out-of-state performance. The criteria 3 language was updated in House Bill 164 of the 133rd General Assembly to ensure that only out-of-state schools in their first year qualify.

[2] As new startups in 2020–21, none of the six schools added to the quality schools list under criteria 2 had school ratings data for 2018–19. Note also that the design of the performance index and value-added measures were consistent between 2017–18 and 2018–19, so the improvements aren’t a reflection of a policy change.

[3] Should the program be reauthorized, the FY 2022 list would likely be the same as the FY 2021 list of qualifying schools due to the suspension of school ratings in 2019–20 and 2020–21. The FY 2023 list could be compiled based on 2021–22 ratings, with schools meeting the criteria in FY 2021 still being eligible under the provision that allows schools to retain their quality status for two subsequent years.

Ohio is making strides in education data transparency—but there’s still work to do

In early December, InnovateOhio—a statewide initiative that aims to use technology to make state government more efficient and effective—announced the launch of the new DataOhio Portal. It is the culmination of a year’s worth of work by InnovateOhio and various state agencies to provide the general public with access to over 200 datasets and more than 100 interactive tools.

The datasets cover a wide range of issues. For example, there are ten linked to data compiled by the Department of Higher Education. They include measurements such as the number of degrees and certifications awarded each year by Ohio institutions, outcomes for graduates who remain in the state after graduation, and earnings and educational attainment data disaggregated by county.

But that’s not all. DataOhio highlights several education-related projects that centralize data in specific virtual locations. Three of these projects should prove enormously helpful to education advocates and researchers now that they’re so easily accessible.

Ohio labor market information

This project and its associated website are the result of a partnership between the U.S. Department of Labor and the Bureau of Labor Market Information within the Ohio Department of Job and Family Services. The bureau analyzes industry, occupational, and employment statistics, conducts research, and publishes data like the employment projection reports used to identify in-demand jobs. Such information is crucial for schools and CTE providers as they design programs and counsel students about their future career paths.

Workforce success measures

The Governor’s Office of Workforce Transformation and the Ohio Education Research Center partnered on this project to produce an interactive database that uses a common set of metrics to display the success rates of Ohio’s largest workforce development programs. Like labor market information, analyzing the outcomes of workforce programs is a vital part of ensuring that students have access to quality programs.

The database offers two lenses through which to view the data. The “spotlight” option provides an overall summary of program characteristics, participant demographics, and outcomes during the most recent year at the state and county level. The “program outcomes” option, meanwhile, reports more detailed information about outcomes over time. That includes the number of completers, median earnings, postsecondary enrollment, and credential attainment at the state, county, and program levels.

Educational attainment dashboard

As part of its efforts toward meeting Attainment Goal 2025, the Ohio Department of Higher Education publishes the Attainment Dashboard. This dataset includes a wide range of indicators that impact postsecondary attainment, such as ACT scores, FAFSA completion rates, graduation and retention statistics, scores on state assessments administered during eighth grade, postsecondary enrollment, and certificate completion numbers. These data, which are updated annually and can be disaggregated in a variety of ways, are crucial for educators, advocates, and policymakers who are responsible for crafting policies and initiatives that improve K–12 schooling and, as a result, postsecondary attainment.

***

What does this influx of easily accessible data mean for Ohio? Well for starters, it’s a giant step in the right direction in terms of transparency. Ohio agencies have been collecting much of this data for years now, but most of it hasn’t been easy for the general public to navigate. By creating a single data portal that houses the information—and links to other, related informational sources—Ohio leaders have demonstrated their openness to public feedback and their commitment to using data to improve the lives of their constituents.

It also means that it’s far easier for researchers, advocates, and lawmakers to access data that can help them shape the education policies that affect thousands of Ohio students and families. Rather than throwing a dozen different initiatives at schools and hoping one sticks, leaders from the education, business, and public policy sectors can analyze the same datasets and collaborate to create data-driven solutions. These solutions could help close achievement gaps, increase attainment numbers, and improve the average Ohioan’s experience with K–12 and postsecondary education institutions.

Despite all this good news, though, it’s important that Ohio leaders don’t rest on their laurels. Now that the state has a strong foundation for data transparency, the next logical step is to get even more detailed about the data that education institutions track and report. This is especially true when it comes to the industry recognized credentials earned by secondary students. An increasing number of students are earning these credentials, but we don’t have clear information about which credentials they’re earning or their value in the workplace. Linking individual credentials to workforce outcomes—or, better yet, linking the entire K–12 sector to workforce outcomes on a much broader scale—would be a wise next move, particularly since we now have a workable blueprint for how to make it happen.

Ohio should rely on direct certification to identify and fund poor students

For decades, education reform has focused on removing barriers that keep low-income students from reaching their potential. Among the notable efforts include expanding educational options for disadvantaged families, holding schools accountable for academic outcomes, and providing extra resources to educate children growing up in poverty.

Of these policy strands, school funding has received the most attention lately in Ohio, with the Cupp-Patterson plan driving much of the discussion. One of its provisions—a praiseworthy one at that—is to increase the amount of additional money allocated to districts and charter schools based on their enrollment of economically disadvantaged students. The effectiveness of the program hinges in part on the accurate identification of low-income students to ensure that the extra resources are allocated appropriately based on need.

But what if identifying economically disadvantaged students isn’t as easy as it sounds? A new report from the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) discusses current problems in spotting economically disadvantaged children. Importantly, it also outlines options that could yield more precise headcounts moving forward. Though it may sound wonky, identification issues are clearly of interest to lawmakers, as the report was issued in response to legislation that asked the agency to review its current method of identification and to investigate other states’ procedures and funding models.

First, let’s review the challenge. As many in education know, states, including Ohio, have traditionally flagged children as economically disadvantaged based on their eligibility for the free and reduced price lunch program (FRL). Students whose families earn at or below 130 percent of the federal poverty guidelines are allowed free meals, while those between 130 and 185 percent can receive reduced-priced ones (the income thresholds by household size are here). As the ODE report discusses, incomes are generally verified through the completion of an FRL application form or through “direct certification.” The latter method refers to an electronic process that matches students to their families’ participation in SNAP or TANF—federal programs that are open to those with incomes at or below 130 percent of the poverty guidelines.

For many years, tying economically disadvantaged status to FRL eligibility made sense. But in more recent times, the rise of the federal Community Eligibility Provision (CEP) has made this linkage problematic. Under CEP, qualifying districts or schools may provide all students free meals, regardless of whether they come from a low-income family. While this supports nutritional goals, avoids stigmatizing children, and reduces administrative burdens, hundreds of schools—and a number of entire school districts—now report 100 percent of their students as economically disadvantaged. In many of these schools, the universal classification now significantly overstates the actual number of low-income students.

Inflated counts have a deleterious impact on policy and public perceptions. In school finance, it means that CEP districts and charter schools are being somewhat “overfunded” relative to their actual needs based on economically disadvantaged enrollments. In a 2019 analysis, I estimated that roughly $50 to $65 million per year in state funding was being misallocated due to identification issues. Those funds might be better spent on other pressing educational needs, such as special-education or supporting other at-risk students (e.g., those who are homeless or in foster care). They also create problems in school accountability and reporting systems. When a district or school reports its students as 100 percent economically disadvantaged, it’s impossible to tell from state assessment data how well it’s serving the children who actually are low-income. Lastly, universal identification may lead to somewhat exaggerated conceptions of poverty in Ohio schools.

Considering these issues, the ODE report concludes: “Continuing to count all students in CEP schools and districts as economically disadvantaged is not a viable path forward; most states have or are planning to move away from this approach.” But how should Ohio address these problems?

While various options exist, the most promising avenue is to rely on direct certification—not FRL eligibility—to identify economically disadvantaged children. Such a move should come with one addition. Because direct certification identifies only students at or below 130 percent poverty (the SNAP and TANF cutoff), it wouldn’t reflect students with incomes between 130 and 185 percent poverty. One way to capture pupils in the higher income range (apart from paper forms) is to include Medicaid participation in the direct certification process, something that nineteen states have already done. In addition to capturing children in the higher income range—the threshold for Medicaid is 185 percent of poverty—it could also help identify poor students whose families don’t participate in SNAP or TANF. ODE does mention some legal and logistical hurdles in incorporating Medicaid into direct certification; if necessary, the governor or legislature should act quickly to clear any roadblocks.

ODE has statutory authority to define which students are economically disadvantaged, so it could make changes unilaterally. However, it would likely be prudent to gain more widespread support before making a shift. To that end, state lawmakers and local leaders need a clear understanding of the current problems and they need to recognize the consequences of misclassifying students.

At the same time, policymakers should also appreciate the benefits of more accurate headcounts. As Ohio debates school finance policy, for instance, lawmakers might consider leveraging direct certification information to drive even more dollars to the lowest income students by including a higher funding multiplier for children at or below the 130 percent income threshold (as suggested here and something that Minnesota does). But all this starts with reliable data. If Ohio can improve its identification methods, state and local policymakers will be able to more effectively target funding and interventions to the children who need the extra help.

Open Enrollment and Student Diversity in Ohio’s Schools

Approximately 85,000 Ohio students use interdistrict open enrollment to attend a neighboring school district. Titled Open Enrollment and Student Diversity in Ohio’s Schools, this new report examines whether these student transfers are creating more diverse schools, or possibly worsening segregation.

To assess this question, Dr. Deven Carlson of the University of Oklahoma compares current segregation levels across Ohio’s 600 plus school districts to a counterfactual in which all students attend their home district (i.e., no open enrollment). Based on his analysis of Ohio Department of Education data for the 2012–13 to 2017–18 school years, the following findings emerge.

- Ohio school districts are highly segregated by race. As of 2017–18, 70.0 percent of Black students would need to change districts to achieve an even distribution (that is, each district’s enrollment would reflect the state average of Black students). Segregation levels in Ohio are higher than the national average where 61 percent of Black students would need to relocate.

- Ohio school districts are moderately segregated by socio-economic status. Data for 2017–18 indicate that 49.8 percent of economically disadvantaged students in Ohio would need to move in order to reach an even distribution.

- Interdistrict open enrollment has virtually no effect on segregation across Ohio school districts. Without open enrollment, 69.6 percent of Black students would have needed to relocate in order to achieve an even distribution (instead of 70.0 percent). The impacts by socio-economic status are likewise very small.

- Open enrollment does not appear to impact segregation at an individual school level. Although detailed analyses for individual schools were not feasible, relying on simulations, Carlson finds little evidence to suggest that open enrollment has significantly increased or decreased segregation across Ohio’s roughly 3,000 district schools.

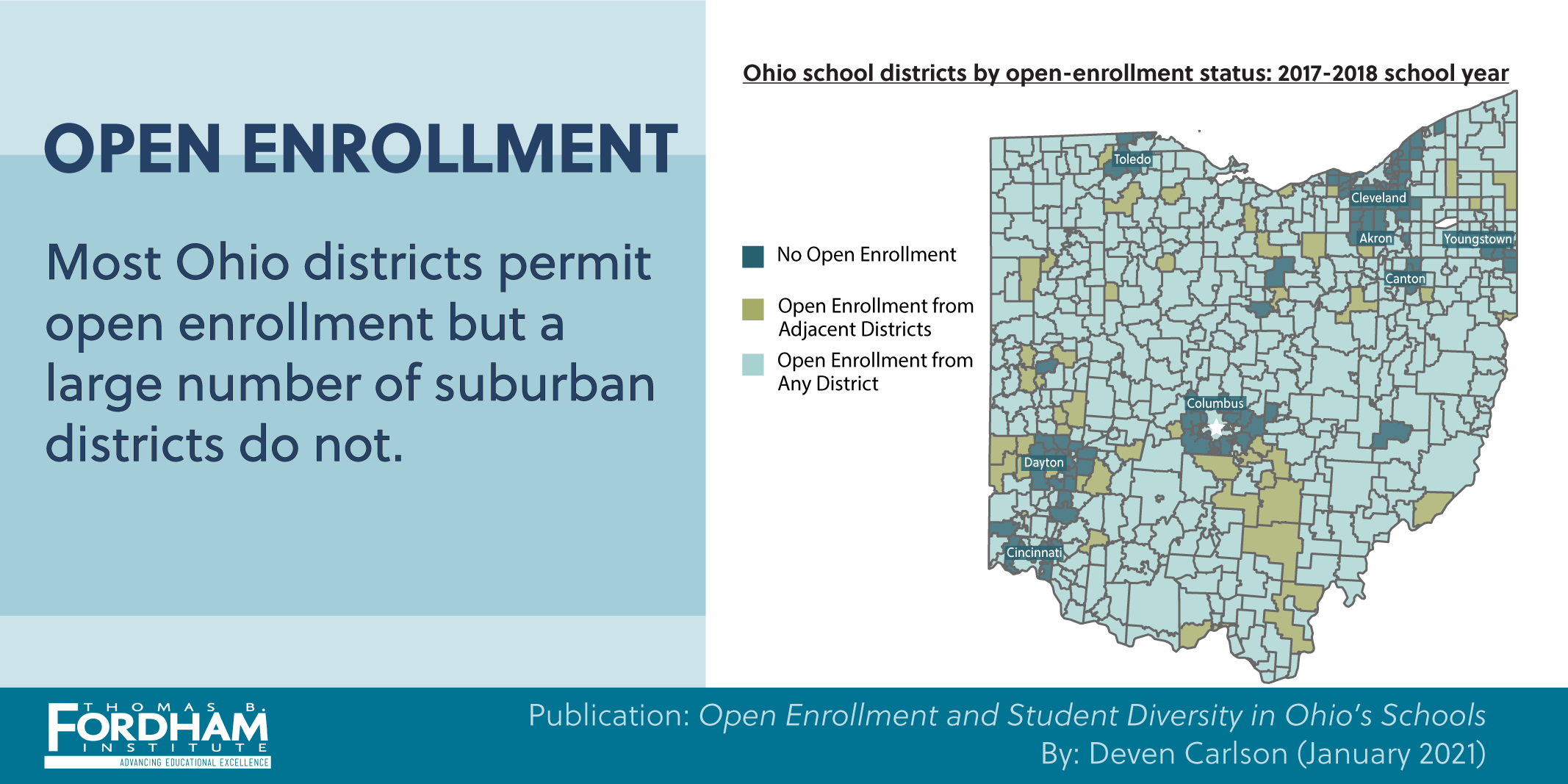

Currently, about eight in ten Ohio districts voluntarily participate in open enrollment. However, many suburban districts choose not to accept non-resident students—the map in the infographic below displays the geographic pattern of opt-outs for the 2017–18 school year. The lack of participation among more affluent districts, plus the relatively small share of the overall population represented by open enrollers, helps to explain the minimal impacts of open enrollment on student diversity.

To leverage the potential of interdistrict open enrollment as a tool for increasing access to quality public schools and to encourage more school diversity, we offer two policy recommendations: 1) all schools districts, subject to their capacity, should participate in open enrollment and 2) open enrollees should have viable transportation options. Download this report now to learn more about the analysis and to read our policy recommendations.