House plan imperils some EdChoice recipients

The raucous debate over school choice took yet another turn last week as the Ohio House approved an amendment that would overhaul the EdChoice program.

The raucous debate over school choice took yet another turn last week as the Ohio House approved an amendment that would overhaul the EdChoice program.

The raucous debate over school choice took yet another turn last week as the Ohio House approved an amendment that would overhaul the EdChoice program. The lower chamber’s plan emerges alongside a Senate-passed proposal as legislators continue talks on the future of the state’s main private-school scholarship program.

As most Gadfly readers know, Ohio has two EdChoice programs. In the performance-based model, scholarship (i.e., “voucher”) eligibility hinges on public schools’ ratings on the state report card. The income-based model, on the other hand, is tied to family income. The House proposes scrapping the performance-based EdChoice program, which has been at the center of the recent uproar, and relying instead on the income-based model.

At face value, this policy shift has some merit. In fact, we at Fordham have recommended a move in this direction, as it would focus attention on the needs of low- and middle-income families, streamline EdChoice, and alleviate some of the adversarial nature of the state rating system.

But as policy wonks are rightly quick to say, “the devil’s in the details.” Though very likely unintended, the details of the House proposal would endanger private-school choice, especially over the long haul. Let’s consider four concerns about the plan.

1. Makes thousands of students immediately ineligible for private-school choice.

One of the flashpoints in the debate over EdChoice is how many public schools should be on the voucher eligibility list under the performance-based model. Prior to the passage of stopgap legislation on January 31, approximately 1,200 schools were scheduled to be designated in 2020–21—a sizeable increase compared to the 517 in 2019–20. Roughly speaking, that would have doubled the number of students eligible to participate in the program. Seeking to address concerns about this rapid growth in eligibility, the Senate proposal would reduce the number to 426 schools, eliminating all of the increase in eligibility and then some.

Yet the House goes even further. By ending first-time eligibility for the performance-based voucher, the House effectively reduces the number of designated schools to zero. Aside from a few minor exceptions, only returning performance-based recipients would be able to receive this scholarship in 2020–21. That means a student who attends a chronically low-performing school—one that has long been designated under EdChoice—could no longer apply for this voucher. While she may be able to apply for an income-based scholarship, there is no assurance that she’ll receive one, as funds for that program may run out. (She also might not be poor enough to qualify.)

2. Does not guarantee that current EdChoice recipients will keep their scholarships after next school year.

In an effort to rapidly unwind the performance-based program, the House plan forces students who receive that type of scholarship in 2020–21[1]—and who also meet the income eligibility guidelines—to apply for an income-based voucher instead. Because a large proportion of the 30,000 students who use a performance-based scholarship are low- to middle-income,[2] this provision will result in a large influx of students applying for the income-based scholarship. As a result, upwards of 40,000 returning EdChoice recipients are likely to apply for an income-based scholarship in FY 2022.[3]

That’s a big problem because the income-based program is funded via line-item appropriation in the state budget. And the FY 2021 amount of $121 million supports only around 25,000 scholarships. Unless legislators significantly increase this amount in the next budget cycle or implement another funding mechanism, thousands of returning students won’t receive a scholarship in FY 2022 and could be forced to leave their current schools.

3. Limits scholarship opportunities for first-time applicants, including newly eligible, middle-income Ohioans.

To its credit, the House plan increases the eligibility threshold for the income-based EdChoice scholarship to families with incomes at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty guideline (up from 200 percent now). Although this does not match the Senate’s proposal to raise the cut-off to 300 percent, this a step in the right direction toward broadening private school opportunities for working-class Ohioans.

Yet because the number of income-based scholarships are capped by the line-item appropriation, many of these newly eligible families who apply for a voucher may not actually receive one. Priority is given to returning students and, as explained above, there will likely be more than enough of those to claim most, if not all, of the available scholarships.

4. Exposes EdChoice to wholesale repeal via line-item veto.

Speaking of line-item appropriations, this manner of funding EdChoice puts the entire program—both the current performance-based and income-based recipients—at risk of a line-item veto.[4] While such a veto is not an immediate concern, it’s always possible that an anti-choice governor would eliminate the program with one stroke of the pen. Doing so would leave tens of thousands of Ohio students without the support necessary to attend the school that their parents believe best meets their needs.

* * *

The House’s decision to shift gears to an income-based EdChoice is not unreasonable. But such a significant policy transition has to be done with great care to avoid jeopardizing the scholarships of existing participants and leaving expectant families stuck on waitlists. More attention needs to be given to how to fund existing scholarships and how to insulate them from future ideologically-driven attacks.

As Senate and House members continue to work on legislation that impacts Ohio families and schools, the policy details will matter tremendously. With any luck, they’ll get them right.

[1] These would mostly be returning scholarship recipients from 2019–20.

[2] As of 2012-13, 90 percent of students in the performance-based EdChoice program were economically disadvantaged (more recent data are not available).

[3] At least 15,000 students are likely to reapply for the income-based scholarship.

[4] The performance-based EdChoice is not exposed to a line-item veto because it is presently funded via deduction from districts’ state allocations. The income-based EdChoice, however, is currently exposed to such a veto.

For the past several years, there has been a steady push by traditional education groups in Ohio to weaken state accountability and school report cards in particular. In 2018, there was a concerted effort to ditch Ohio’s A–F grading system in favor of a dashboard model that would display academic data in raw numbers rather than letter grades. In 2019, debates over academic distress commissions routinely focused on report cards and whether they adequately take into account demographics. This year, the ongoing kerfuffle over vouchers and the significantly larger list of EdChoice eligible schools for the 2020–21 school year has generated similar criticism.

Without a doubt, Ohio’s accountability system could use some adjustments. (Here at Fordham, we’ve made several common sense recommendations.) But if lawmakers are serious about revamping report cards this year, it will be vital for them to heed not only the viewpoints of school officials, but also parents. After all, one of the primary and most important functions of state report cards is to provide families with clear, accurate, and easily understandable information about their local schools.

But what, exactly, do parents think about state report cards? Ohio Excels, a nonprofit coalition of business leaders dedicated to improving education, recently commissioned a survey of Ohio parents to find out. The survey, conducted by Saperstein Associates, collected responses from a representative sample of 655 Ohio parents with at least one child enrolled in a public school. Let’s take a look at three big takeaways.

1. Parents value report cards

Results indicate that a majority of Ohio parents recall having seen either district or school report cards, though only 24 percent said they’ve seen both the district and school version. 89 percent found school report cards to be very or somewhat important, and 91 percent registered similar support for the district version. These results should be a clear sign to lawmakers that a vast majority of their constituents value report cards and are paying attention to what they say.

The survey also asked about specific measures. Nearly all parents—a whopping 95 percent—reported that they value having a measure of reading proficiency on report cards for districts and elementary schools. A similarly high number, 91 percent, said they value having a rated indicator on district and high school report cards that measures student success after graduation. It’s not surprising that parents are interested in reading and postsecondary success—most moms and dads will tell you that they care deeply about whether their child can read and is prepared for life after graduation. But it is worth noting that elementary reading proficiency and postsecondary readiness have traditionally been two of the most controversial topics in Ohio education policy. Based on the results of this survey, it seems as though recent and heated debates about the Third Grade Reading Guarantee and graduation requirements haven’t altered what parents want from state report cards—clear and accurate information about what their kids have learned and what they are prepared to do.

2. Parents prefer big picture summaries before data deep-dives

To determine the preferred type of format for online report cards, parents were asked to select between two options. Option 1 provides a letter grade for overall performance and for each measure. It then offers detailed information on each indicator. Option 2, on the other hand, provides all the details upfront without first providing a summary. Of those parents with a preference, 66 percent preferred a format that started with a summary, compared to 23 percent who preferred the opposite. These numbers indicate that clarity is important to parents and that they prefer to have a simple and easily understandable rating rather than a chunk of information they need to decipher and interpret.

3. Parents think letter grades are a clear and appropriate way to express school performance

In previous years, Ohio used descriptors like “effective” and “continuous improvement” that were vague and hard to parse. The state made the switch to using an A–F scale during the 2012–13 school year. Based on survey results, it appears parents approve of that decision—91 percent agree that as a measure of performance, letter grades are clear and easy to understand. Eighty-seven percent also agree that letter grades are an appropriate way to express the overall performance of a school district.

Despite strong parental support, several alternatives to A–F grades have been suggested by education groups and could soon be proposed by lawmakers. To determine which option parents might prefer, the survey asks respondents to identify whether three alternative options were “more appropriate” than letter grades. The alternatives include a 0–100 numerical score, a description in words (such as “below expectations”), and a scale of one to five stars. None of the alternatives was identified as more appropriate, though a good chunk of parents identified each of the three alternatives as “about the same” as letter grades. When asked to identify the best measure of performance out of the four options, letter grades proved to be the most popular, with 38 percent of parents identifying them as the best option. The numerical score earned 30 percent of the vote, word descriptors earned 24 percent, and the star system earned 8 percent. The upshot? Letter grades are pretty popular, but parents are open to other options.

***

There’s no way of knowing whether 2020 will be the year that lawmakers revamp state report cards. But if they’re serious about making changes, they would be wise to read the results of this survey carefully. Parents aren’t just voting constituents. They are the primary audience for report card measures, and they use school performance information to make serious decisions that will have long-term impacts on their children. The state has a responsibility to provide families with clear, accurate, and easily understandable information so that every parent can make the choice that’s best for their child.

Politics is sometimes called the “art of compromise.” Under tremendous pressure from school systems, Ohio legislators for the last few weeks have sought to find a compromise on EdChoice—Ohio’s largest voucher program—that addresses district concerns about the rate of growth and cost while also honoring families’ right to choose a school.

After a couple weeks of intense negotiation, the legislature wasn’t able to reach an agreement by the time the voucher application window was supposed to open on February 1. Instead, it decided on January 31 to postpone until April 1 the opening of applications for the 2020–21 school year. Regrettably, this delay puts scholarship-seeking parents in a limbo, but it does buy legislators some more time.

As most Gadfly readers know, the center of attention is the state’s EdChoice program. Launched in fall 2007, this program has unlocked private-school opportunities for thousands of students by providing state-funded scholarships for their education. Ohio has two EdChoice programs, one in which eligibility is based on low ratings on the state report card, and the other linked to household income. The former has come under blistering attack as the number of public schools in which students are eligible is slated to rise markedly this coming fall. Fearing the loss of money when students use vouchers, officials have pulled out all the stops in trying to obstruct this expansion.

What to do? It may not be perfect, but the Senate-passed proposal to modify EdChoice provides a potential path forward. The upper chamber’s plan would significantly reduce the number of public schools designated for EdChoice—a concession to the traditional education system—but also ensures that most families who need the financial aid to attend private schools will receive it by expanding eligibility for the income-based scholarship. Under current policy, Ohioans with incomes at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty guidelines are eligible for EdChoice. The Senate amendment, however, raises the threshold by allowing families earning 200 to 300 percent federal poverty to apply for a full scholarship as well.

On the one hand, the Senate amendment would halt an impending expansion of scholarship eligibility under the report-card model. This addresses a main grievance of district officials who are not only concerned about potential downsizing, but also frustrated with the school rating system. Due to intricate changes in state policy—already delayed for several years under safe harbor—students slated to attend about 700 additional schools would’ve become eligible for EdChoice in the 2020–21 school year. The Senate amendment, however, actually cuts the number of schools on the EdChoice list by about 100 schools, down from the 500 or so currently designated.

Without a doubt, this aspect of the proposal would deal a blow to school choice. It would certainly sting for any family whose plans are ruined because of the alterations. Patrick O’Donnell of the Cleveland Plain Dealer recently interviewed a working parent who was banking on the expanded eligibility to send his child to a local Catholic school. He said, “Once we saw that Normandy High School [the district option] was added, we were able to breathe a little easier. We looked at each other and said, ‘This will work.’” As suggested in a Gongwer report, a number of parents seem to have started purchasing school uniforms in expectation of a scholarship—to which one senator made the rather tactless remark, “I suspect that if they have bought uniforms, they can send them back.” This isn’t just about uniforms, of course. Rather, the deliberate breaking of promises to certain parents is what’s most distasteful about any last minute “fix” to the EdChoice list.

Some of these families may qualify under the new income-based rules. But even then, there’s no guarantee they’d receive a scholarship in the coming year. Funds for the income-based program could run out as those scholarships are limited by the state budget appropriation, a constraint that is already leaving parents stuck on a waitlist. Current law, continued under Senate amendment, gives priority to returnees and families under 100 percent poverty should there be more applicants than scholarships. After that, it’s by lottery. Sadly, it would indeed be “highway robbery,” as one choice advocate put it, for any parent left on the outside looking in.

Fortunately, the Senate amendment also has an important choice-friendly dimension. Expanding and placing more emphasis on the income-based model—an idea that House Speaker Larry Householder recently floated and something that we at Fordham have recommended—has several advantages.

Overall, there’s both sweet and sour in the Senate amendment for advocates on all sides of the EdChoice issue. It’s a compromise, to be sure. Most importantly, it would put Ohio on a surer pathway to ensuring that all families have the ability to choose a school that meets their child’s needs.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

In this article, we explore the most recent version of the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System (OTES) and how this legislative requirement holds out hope for transforming our state and our profession. The article is organized around the historical and legislative contexts that brought us to our current, third, version of OTES, the changes forthcoming, and next steps for our state that prides itself on improving instruction through standards-based conversations with teachers.

Historical Context

Ten years ago, then Secretary of Education Arne Duncan, proclaimed to millions of educators that due to the Recovery Act (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, 2009), almost $100 billion in new resources would be coming to schools and kids everywhere (Duncan, 2009). This statement was justified through data: “It tells us that something like 30 percent of our children, our students are not finishing high school. It tells us that many adults who do graduate go on to college but need remedial education. They're receiving high school diplomas, but they are not ready for college.”

Following this announcement, state educational agencies (SEAs) were encouraged to apply for competitive grants that would encourage our educational system to move toward a focus on college and career readiness. This grant process, known as Race to the Top (2009), was designed to spur and reward innovation and reforms in state and local district education through certain educational policies, including instituting performance-based evaluations for teachers and principals based on multiple measures of educator effectiveness in hopes of improving college and career readiness (USDOE, 2009).

Ohio Context

The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) was awarded a Race to the Top grant. In the application, ODE indicated they would “collaborate with Local Education Agencies (LEAs) and teacher unions to develop a teacher evaluation model that includes annual evaluations, provides timely and constructive feedback, includes student growth as a significant factor, and differentiates effectiveness using multiple rating categories. The development of a model evaluation system for teachers is a core initiative” (Strickland, Delisle, Cain, 2010).

Following the application and acceptance of funds, Ohio House Bill 1 directed Ohio’s education standards board to develop a model teacher evaluation plan and framework (NCTQ, 2011). Subsequent pieces of legislation, Ohio House Bill 153 and Senate Bill 316, required districts to design and revise their teacher evaluation protocols to conform with the state model. This system became known as OTES, the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. OTES was required under revised code to be implemented beginning the 2012-2013 or 2013-2014 school year, dependent on the expiration of local school district collective bargaining agreements.

The OTES Framework

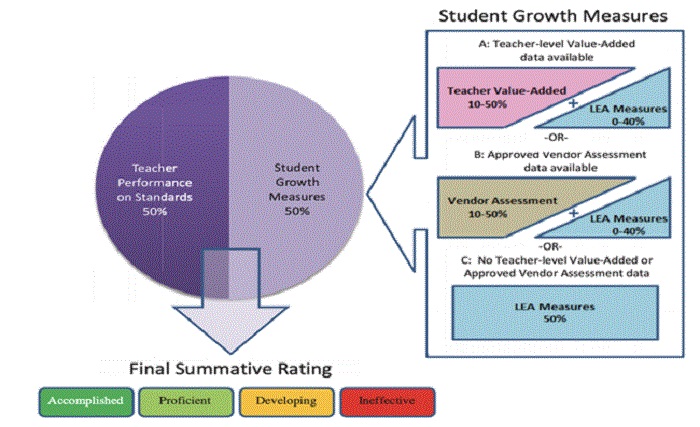

The original OTES was comprised of two components, as illustrated in Figure 1 (NCTQ, 2011): (1) a 50% performance rating determined by a holistic score on a rubric based on observations and walkthroughs; (2) a 50% student academic growth rating based on one of three measures dependent on the type of data available for a teacher (a) EVAAS (Education Value-added Assessment System) data where applicable for state tested areas; (b) Vendor Assessments approved by the ODE in non-tested areas; (c) local measures that comprise of Student Learning Objectives (SLOs) or Shared attribution, growth measures attributed to a district or group of buildings to encourage collaboration (see NCTQ, 2011, p. 8 for a detailed discussion of these terms).

Figure 1: Original OTES components, 2011

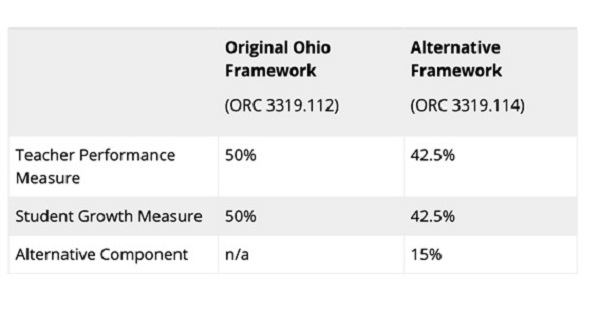

In 2014, following perceived concerns from the field regarding principals’ abilities to complete evaluations timely and concerns regarding the 50% attributed to student growth, the Ohio legislature passed Substitute House Bill 362. This reform bill allowed school districts with teachers who had high ratings to be evaluated less frequently, while still providing them with feedback on their work. Secondly, the bill revised the framework to offer school districts a choice between the original student growth measure structure and a new alternative structure allowing for 15 percent of the evaluation to be measured through student surveys, teacher self-evaluations, peer review evaluations or student portfolios, with the remaining portion divided equally between performance on standards and student growth measures. (See Figure 2 (ODE, 2017). Districts to this day have the ability, through collective bargaining negotiations, to choose one of the two frameworks.

Figure 2: OTES changes, 2017

What Does the Data Tell Us?

OTES was based on the belief that the education profession needed to improve preparation of students for college and careers. Given this system has now been in place since 2013 in one form or another, as Mr. Duncan decreed, what is the data telling us about this mission? Is our evaluation system helping teachers to prepare students for college and careers at better rates?

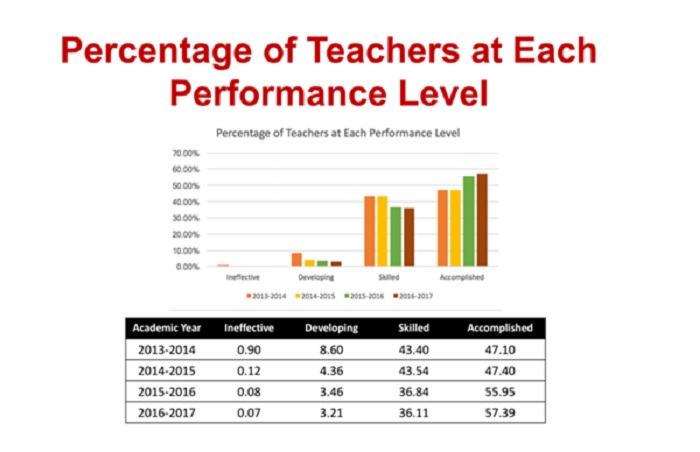

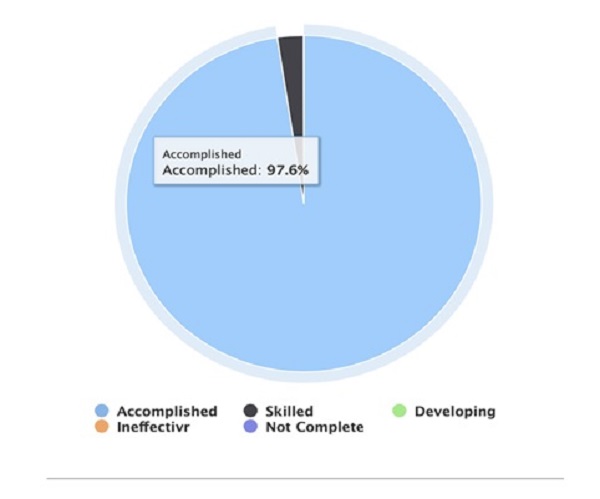

To answer these questions, two data sources are critical: the results of the OTES process and state achievement data. The OTES data is relatively simple: as explained in Figure 3, the majority of our teachers score at the highest performance level (accomplished), even from the program’s inception, and that number increases from year-to-year (ODE, 2019). This accomplished designation means “the teacher is a leader and model in the classroom, school, and district, exceeding expectations for performance” (NCTQ, 2013, p. 23) This is an interesting conundrum given the fact that the program’s own model indicates that the skilled (formerly known as proficient level) is “the rigorous, expected performance level for most experienced teachers” (p. 23).

Figure 3: Performance Level of Teachers in OTES

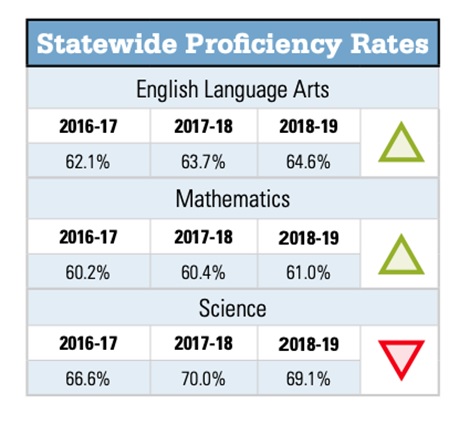

In relationship to student achievement data, growth from the report card shows achievement numbers are increasing as measured by state achievement tests in almost all areas. (See Figure 4. Some argue this is due to the relative consistency of assessment measures.

Others contend improved results indicate better teaching and improved dialogue with teachers about performance. Regardless of the interpretation, if achievement scores have increased, an argument can be made that the number of ratings for evaluation would increase and more teachers would be performing at higher levels (accomplished and skilled), which seems to be the case.

Figure 4: Statewide Proficiency Rates

What becomes interesting is what happens when the data is disaggregated by individual district. For example, the highest performing district (meeting 100% of the indicators and having the highest performance index in the state) has 97.6% of its teachers functioning at the accomplished level, and 3.4% functioning at skilled (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Teacher skill levels for highest performing district

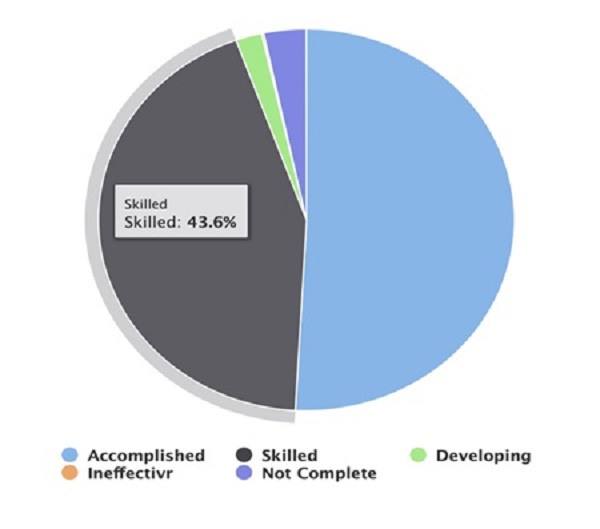

One would expect the same thing to happen at the low levels of the scale; however, this is not what happens. Take the district in figure 6 that ranks approximately 50th from the bottom of the 608 school districts in Ohio. The district earns 3 out of a possible 24 indicators met and scored a D on their performance index (64.5%). Yet, over 90% of their teachers perform at the two highest levels on the evaluation rubric.

Figure 6: Teacher skill levels for a low performing district

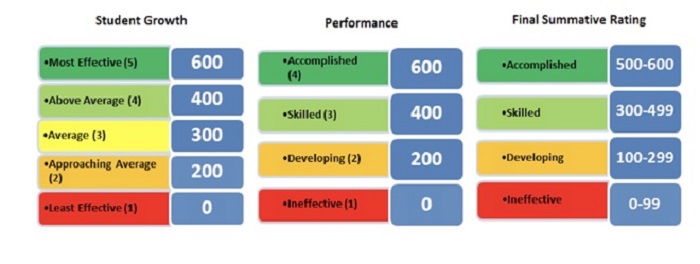

One would hope this would be an anomaly, but unfortunately the district is not unique! In several cases, there are district results whose achievement measures have decreased, and yet teacher evaluation ratings have increased! Possible reasons for this include the fact that due to the numerical conversion (as illustrated in Figure 7) in calculating the final summative rating for a teacher, it is possible for the less objective observation component to overshadow the student growth measure. Specifically, a teacher who receives a score of accomplished in the observation component and receives least effective growth would be rated as skilled ((600+0)/2 = 300). A second reason can be due to shared attribution where teachers receive often a higher rating than they themselves did not personally earn. Rather the shared student growth results of an entire district performance on the entire district report card, improved the teacher’s student growth measurement. A third reason was related to very subjective, teacher created student learning objectives that were often designed and controlled by the same individuals who they were intended to measure.

Figure 7: Numerical conversions for final summative ratings

Whether or not one agrees with the measures or calculations, the data indicates the evaluation system was not producing students who are better prepared for college and careers as was intended nor teachers who are better teachers. Accordingly, legislators have responded to the data analysis, public concern with the evaluation system, and consequently voted to implement a new, third OTES model for the 2020-2021 (SB 216). One state representative, Teresa Fedor, recently stated that the Ohio General Assembly had to make changes to the evaluation system as it “has been flawed and broken from the very beginning” (Siegel, 2018).

Better Classroom Instruction - Take 3

In rewriting the OTES for the third time, Ohio lawmakers indicated they need to construct a system that teachers and administrators think is fair, not overly burdensome and actually furthers the goal of better classroom instruction. Consequently, the newest revision to OTES requires “at least two measures of high-quality student data (HQSD) to provide evidence of student learning attributable to the teacher being evaluated” (ORC 3319.112). When applicable, the high-quality data will include the value-added progress dimension and one other measure of high-quality student data that demonstrates student learning. Student learning objectives may no longer serve as a student data measurement and districts are prohibited from using shared attribution. The revised model focuses on high-quality data that is specific to the teacher being evaluated.

Other expectations for the state board are to revise the specific standards and criteria that distinguishes between the different rating levels of the OTES rubric. A newly revised rubric has been constructed to align with the changes to the revised OTES model. Specifically, the new rubric now includes an evaluation of high-quality student data that can be used as evidence in any component of the evaluation, which are as follows:

A. Knowledge of students to whom the teacher provides instruction

B. The teacher’s use of differentiated instructional practices based on the needs or abilities of individual students

C. Assessment of student learning

D. The teacher’s use of assessment data

E. Professional responsibility and growth

(ORC 3319.112)

In addition to the inclusion of HQSD throughout the rubric, other areas of the rubric have completely changed. For example, in the 2019 draft of the OTES rubric, a new section on the entitled “classroom climate and cultural competency” has been added. Even though some areas have remained, they have been clarified or rewritten to emphasize important teaching skills. One example of this is in the new lesson delivery section. In the newest version, teachers are required to employ effective, purposeful questioning strategies to check for understanding, increase understanding, involve students in the lesson, and ask challenging questions about disciplinary content, engage students in self-assessment, and adjust the lesson based on student understanding. In the prior version, teachers were asked to have student-led lessons, anticipate confusion by presenting clarifying information before students asked questions, and develop high-level understanding through various types of questions.

More Support for Teachers

Many of the teacher performance criteria continue to be included in the newest revision of OTES such as the number (2) and length (30 minute minimum) of teacher observations and required classroom walk-throughs. A significant difference in the updated OTES framework requires that instead of two holistic observations, the revision now requires one formal holistic and one formal focused observation. The focused observation can relate to the goal(s) set in the professional growth plan and/or administrative suggestions/requirements. Ratings are expected to be assigned for each evaluation and the teacher should be provided a written report of the results of the evaluation. LEAs still have the option for teachers scoring an overall performance rating of skilled or accomplished to receive less frequent evaluation; skilled every two years and accomplished every three. Teachers will also continue to complete professional growth plans (and improvement plans when necessary) to guide their professional growth.

Another change relates to the goal setting for these professional growth plans. Previously, teachers could write goals that did not connect to performance. Under the revised process, teachers will now be required to align their professional goals to identified areas highlighted in the observations and evaluation. This will further support teacher and student learning as goal setting will be tied to the teaching-learning cycle and not be separate from the evaluation. Evidence of growth on the goal could even be demonstrated through the collection of HQSD data.

The Ohio Teacher Evaluation System is intended to support teacher development and improved student achievement. The model requires timely feedback and collaborative goal setting. LEAs are also expected to allocate financial resources to support professional growth. Plans to educate constituents throughout the state regarding the changes to the process and rubric are being developed.

Challenges to the Process

If our goal is to improve student and teacher achievement, how do we support teachers under this new model? As referred to in “The Opportunity Myth,” students need access to four key resources: grade appropriate assignments, strong instruction, deep engagement and teachers who hold high expectations. The challenge currently is that “Even though most students are meeting the demands of their assignments, they’re not prepared for college-level work because those assignments don’t often give them the chance to reach for that bar” (p. 21).

HQSD embedded in day-to-day instruction as the new model prescribes is one way to support this. Given the current draft,

The high-quality student data instrument used must have been rigorously reviewed by experts in the field of education, as locally determined, to meet the following criteria:

(ODE, 2019).

More training and support is needed to support LEAs in designing HQSD that fosters engagement and challenges students in the classroom. Without training and support, there could exist a wide variance of what schools believe to be HQSD and in how the new requirement is implemented. Without consistency, there could be the opposite effect on high teacher expectations and strong instruction.

Consequently, providing training and practice to LEAs is imperative to school improvement. An in-depth study examining the instructional practices in our nation’s classrooms revealed that, “Specifically of the 180 hours in each core subject area during the school year, students spend 133 hours that are not grade appropriate.” (TNTP, 2018). Teachers need to understand and utilize HQSD in their practice to support student learning.

Next Steps

Ohio piloting the revised OTES framework to all Ohio districts and community schools who elect to participate. Participating districts and schools who choose to conduct the pilot must fully implement all components of the system. Statewide implementation of OTES is planned for the 2020-2021 school year.

In order for this OTES model to be successful, schools will need supports. Specifically, training must be offered to help districts and schools recognize and implement HQSD. What makes an effective assessment and how to analyze the results are just some of the questions with which school districts will need support. Additionally, the revised rubric needs to be normed to ensure ratings are consistent across a school, district, and the larger state. Administrators are already asking for concrete examples of what various skills look like within their classrooms. And lastly, more focus will need to occur on the connection between the professional growth plan and the evaluation. As mentioned previously, a focused observation is now required. Ongoing training and support on how to provide strong feedback to teachers and formulate strong questions to evolve teacher self-reflection and practice will support both administrative and teacher development with the OTES revisions.

Ohio may be rounding its third revision of OTES, but there is an evolution to the process versus fresh slate. Revisions are based on student and teacher performance data, surveys and formal feedback from practitioners. As a state, educators continue to challenge themselves to improve instruction and provide more support to teachers and students in the learning process. OTES has been helpful in structuring a system for feedback and improvement in practice.

References

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act. (2009). H.R. 1 — 111th Congress: American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. Retrieved from https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/111/hr1

Duncan, A. (2009). Robust Data Gives Us The Roadmap to Reform. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/news/speeches/2009/06/06082009.html

NCTQ (2011). OTES Training Workbook. Washington, D.C.: NCTQ.

NCTQ (2013). OTES Training Workbook. Retrieved from: https://www.nctq.org/dmsView/OTES_Training_Workbook_Updated

Ohio Department of Education (2017). Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. Retrieved from: http://education.ohio.gov/Topics/Teaching/Educator-Evaluation-System

Ohio Department of Education (2019). High Quality Student Data. Retrieved from:

Ohio Department of Education (2019, February). Ohio OTES Prototype Day 2. Presentation presented at Regional Meeting for Ohio OTES Prototype Day 2 by the Ohio Department of Education, Medina.

Ohio Rev. Code §3319.112 (2018), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/3319.112

Ohio Senate Bill 216. S.B. 216 - 132nd General Assembly: Ohio Public School Deregulation Act.

Race to the Top. H.R. 1532 — 112th Congress: Race to the Top Act of 2011. Retrieved from: https://www.govtrack.us/congress/bills/112/hr1532.

Seigel, J. (2018). Ohio teacher evaluations get an overhaul that teachers like. Columbus Dispatch. Retrieved from: https://www.dispatch.com/news/20180701/ohio-teacher-evaluations-get-overhaul-teachers-like

Strickland, Delisle, Cain (2010). Race to the Top Application: Ohio. Retrieved from: https://www2.ed.gov/programs/racetothetop/phase1-applications/ohio.pdf

TNTP (2018). The Opportunity Myth. Retrieved from: https://tntp.org/assets/documents/TNTP_The-Opportunity-Myth_Web.pdf

As its name suggests, the middle-skills pathway sits between a high school diploma and a bachelor’s degree. There are a wide variety of credentials associated with this pathway, but certificate and associate degrees are the most popular. In general, associate degrees include a mix of general education courses and career preparation, while certificates are almost exclusively career oriented.

Due to a lack of consistent data sources, information on middle-skills pathway credentials is scarce. A recent report from the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce seeks to remedy this by examining certificates and associate degrees using data from the Adult Training and Education Survey, the American Community Survey, and the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System. The report examines three aspects in particular: the prevalence of certificates and associate degrees, the demographic characteristics of the students who enroll in and complete these programs, and the associated labor market outcomes.

The number of certificates and associate degrees awarded by postsecondary institutions is roughly equivalent to the number of bachelor’s degrees awarded. There are approximately two million conferred each year, with certificates and associate degrees each accounting for about one million. The vast majority of these credentials are earned by students attending public two-year colleges.

Students who enroll in and complete certificate and associate degree programs are far more diverse than those who enroll in bachelor’s degree programs. Among undergraduate students, 56 percent of black students and 62 percent of Latino students are enrolled in certificate and associate degree programs compared to 47 percent of white students. Nationally, both black and Latino students earn a higher percentage of certificates and associate degrees than their respective shares of the population. When it comes to socioeconomic status, low-income students are more likely to enroll in certificate programs at two-year public or for-profit colleges and are less likely to earn a postsecondary credential.

While it is generally true that higher education attainment levels lead to higher pay and lifetime earnings, the report shows that the program of study a student chooses matters immensely. In some cases, workers with a certificate or associate degree can earn more than those with a bachelor’s degree. For example, workers who earned an associate degree in engineering have median annual earnings in the $50,000 to $60,000 range, while those with a bachelor’s degree in education earn between $30,000 and $40,000. For workers with middle-skill credentials, the jobs with the best outcomes are those in STEM and managerial or professional vocations. Getting a job related to the chosen field of study also matters; workers who report having a job related to their certificate program have higher median earnings than those who don’t.

The authors were also able to analyze administrative data obtained from ten states with the capacity to link student records to wage records and produce earnings outcomes—Colorado, Connecticut, Indiana, Kentucky, Minnesota, Ohio, Oregon, Texas, Virginia, and Washington. Among the states that provided data, associate degree programs in the health profession ranked in the top five fields of study with the highest earnings. Engineering was also a valuable field: Associate degree programs in engineering technologies were within the top earning fields in every state, and certificates in engineering technology placed in the top five of earnings in eight of ten states. The authors also found additional evidence that, in some states, a certificate or associate degree holder in the right field can make as much as a worker with a bachelor’s degree. In Ohio, for instance, workers with a certificate in industrial technology reach $65,000 in median earnings, which is considerably more than the $45,700 median for workers with bachelor degrees.

The report ends with calls for greater transparency around the labor-market value of middle-skill credentials. The authors note that students need better assurances that their investments of time and money are worth it, and that policymakers and educators should focus on strengthening all pathways to and through college. They also offer several policy recommendations, including expanding federal postsecondary data collection efforts and strengthening accountability for career-oriented programs.

SOURCE: Anthony P. Carnevale, Tanya I. Garcia, Neil Ridley, Michael C. Quinn, “The Overlooked Value of Certificates and Associate’s Degrees: What Students Need to Know Before They Go to College,” Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce (January 2020).

Editor’s note: It’s been almost ten years since the creation of the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System. This post looks at its genesis, troubled implementation, and recent efforts to replace it with something better.

Back in the late 2000s, Ohio joined dozens of other states in applying in the second round of Race to the Top, a federal grant program that awarded funding based on selection criteria that, among other things, required states to explain how they would improve teacher effectiveness.

Ohio succeeded in securing $400 million. As part of a massive education reform push that was buoyed by these funds, the state created the Ohio Teacher Evaluation System (OTES). It aimed to accomplish two goals: to identify low-performers for accountability purposes, and to help teachers improve their practice.

It’s been nearly a decade, but it’s plenty clear that OTES has failed to deliver on both fronts. The reasons are myriad. The system has been in almost constant flux. Lawmakers started making changes after just one year of implementation. The performance evaluation rubrics and templates for professional growth plans lacked the detail and clarity needed to be helpful. Many principals complained about the administrative burden. Teachers’ experience with the system varied widely depending on the grade and subject they taught. The unfairness of shared attribution and the inconsistency of Student Learning Objectives (SLOs) made the system seem biased. And safe harbor prohibited test scores from being used to calculate teacher ratings, and thus the full OTES framework wasn’t used as intended for three straight school years.

Given all these issues, it should come as no surprise that lawmakers and advocates began working to make serious changes to OTES the moment that ESSA went into effect, given that it removed federal requirements related to teacher evaluations. In the spring of 2017, the Educator Standards Board (ESB) proposed a series of six recommendations for overhauling the system. (You can find in-depth analyses of these recommendations here and here.) These recommendations were then included in Senate Bill 216, the same education deregulation bill that made so many changes to teacher licensure.

When SB 216 went into effect in the fall of 2018, it tasked the State Board of Education with adopting the recommendations put forth by the ESB no later than May 1, 2020. This gap in time provided the state with an opportunity to pilot the new OTES framework in a handful of districts and schools during the 2019–20 school year. The Ohio Department of Education plans to gather feedback from pilot participants, and to refine and revise the framework prior to full statewide implementation in 2020–21.

We’re almost halfway through the 2019–20 school year, which means the OTES pilot—referred to as “OTES 2.0” on the department’s website—is halfway done. We won’t know for sure how implementation of the new framework is going until the department releases its findings and revisions prior to the 2020–21 school year. But OTES 2.0 made some pretty big changes to the way student achievement and growth are measured, and some of those changes are now in place and worth examining.

Prior to the passage of SB 216, Ohio districts could choose between implementing the original teacher evaluation framework or an alternative. Both frameworks assigned a summative rating based on weighted measures. One of these measures was student academic growth, which was calculated using one of three data sources: value-added data based on state tests, which were used for math and reading teachers in grades four through eight; approved vendor assessments used for grade levels and subjects for which value added cannot be used; or local measures reserved for subjects that are not measured by traditional assessments, such as art or music. Local measures included shared attribution and SLOs.

The ESB recommendations changed all of this. The two frameworks and their weighting percentages will cease to exist. Instead, student growth measures will be embedded into a revised observational rubric. Teachers will earn a summative rating based solely on two formal observations. The new system requires at least two measures of high-quality student data to be used to provide evidence of student growth and achievement on specific indicators of the rubric.

A quick look at the department’s OTES 2.0 page indicates that the new rubric hasn’t been published yet. One would hope that’s because the department is revising it based on feedback from pilot participants. Once the rubric is released, it will be important to closely evaluate its rigor and compare it to national models.

The types of high-quality data that are permissible have, however, been identified. If value-added data are available, then it must be one of the two sources used in the evaluation. There are two additional options: approved vendor assessments and district-determined instruments. Approved assessments are provided by national testing vendors and permitted for use by Ohio schools and districts. As of publication, the most recently updated list is here and includes assessments from NWEA, ACT, and College Board. District-determined instruments are identified by district and school leadership rather than the state. Shared attribution and SLOs are no longer permitted, but pretty much anything else can be used if it meets the following criteria:

All of these criteria are appropriate. But they’re also extremely vague. How can a district prove that an instrument is inoffensive? What, exactly, qualifies as a “trustworthy” result? And given how many curricular materials claim to be standards-based but aren’t, how can districts be sure that their determined instruments are actually aligned to state standards?

It’s also worth noting that the department requires a district’s chosen instrument to have been “rigorously reviewed by experts in the field of education, as locally determined.” This language isn’t super clear, but it seems to indicate that local districts will have the freedom to determine which experts they heed. Given how much is on the plate of district officials—and all the previous complaints about OTES being an “administrative burden”—weeding through expert opinions seems like a lot to ask.

The upshot is that Ohio districts and schools are about to have a whole lot more control over how their teachers are evaluated. And it’s not just in the realm of student growth measures either. ODE has an entire document posted on its website that lists all the local decision points for districts.

The big question is whether all this local control will result in stronger accountability and better professional development for teachers. Remember, there’s a reason Race to the Top incentivized adopting rigorous, state-driven teacher evaluation systems: the local systems that were in place previously just weren’t cutting it. Despite poor student outcomes and large achievement gaps, the vast majority of teachers were rated as effective.

Of course, that’s not to say that state models are unquestionably better. OTES had a ton of issues, and the student growth measures in particular were unfair to a large swath of teachers. But still, moving in the direction of considerable local control, regardless of whether it’s the wise thing to do, is risking going back to the days when teacher evaluations were either non-existent or a joke. Teacher quality isn't the only factor affecting student achievement, but it is the most significant one under the control of schools. Here’s hoping that districts take their new evaluation responsibilities very, very seriously.