Reading is essential to functioning in today’s society. Job applications, financial documents, and instruction manuals all require basic literacy. Above that, our lives are greatly enriched when we can effortlessly read the printed word. Thankfully, most of us don’t struggle to read, but roughly 43 million American adults—about one in five—have poor reading skills. Of those, 16 million are “functionally illiterate.”

Given the vast importance of literacy, a central task of schools is to help children learn to read. It’s one reason why we spend billions to support K–12 education. It’s also why a number of states, including Ohio, have policies that aim to ensure that their youngest students get a strong start in reading. As studies indicate, children who are poor readers early in life usually don’t catch up.

Here in Ohio, the Third Grade Reading Guarantee has been on the books since 2012. The guarantee’s most well-known provision requires schools to retain third graders and give them intensive interventions if they don’t meet reading standards. Other policies included in the overall package are mandatory diagnostic testing, parental notification when students are off-track, and intervention guidelines.

Ten years into implementation, state policymakers continue to debate the guarantee, with some seeking to remove the retention provision. With data showing that more children are faltering in reading due to the pandemic, the time is ripe to revisit the policy and make sure that it’s as strong as possible. What are its strengths and weaknesses? And how might it be improved? This analysis focuses on the retention requirement, while a future one will look at other provisions in the guarantee.

First, why retention? The primary aim is to give struggling students more time and support to build the foundational reading skills needed for lifelong success. Unfortunately, that “gift of time” hasn’t always been available due to the habit of “social promotion,” whereby students advance to the next grade regardless of their skills and abilities. In the years before the guarantee was enacted, it was exceedingly rare for Ohio third graders to be retained—usually just 1 percent. Now that the guarantee is in place, around 5 percent are held back. Another critical goal of the retention policy is to encourage schools to adopt effective reading practices—naturally, no one wants to hold back a child—thus lifting achievement more broadly for all children in the early grades.

Despite these important purposes, critics claim that retention does students little good or may even do harm. But rigorous studies from places like Florida and Chicago find that retention, especially when paired with effective interventions, gives students a significant boost. Although no comparable study has been done in Ohio, the state’s rising third grade reading scores prior to the pandemic suggest that the policy might be having a positive impact.

The retention requirement is a crucial lever to ensuring that all children gain necessary reading skills, and it ought to remain a centerpiece of the reading guarantee. Nevertheless, some of the policy details could use refinement. Here are three areas that lawmakers should focus on.

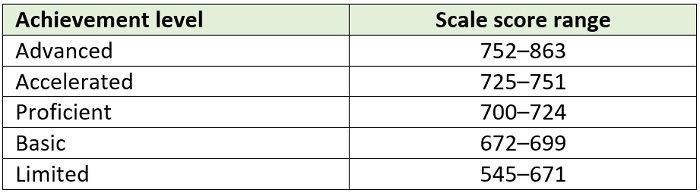

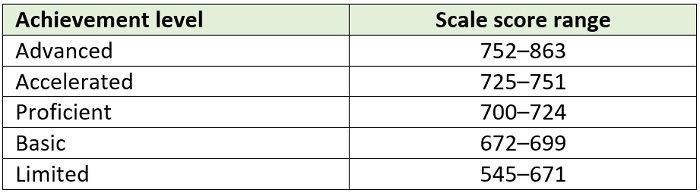

1. Establish a fair, permanent promotional standard. In an effort to ease-in the new retention requirement, the guarantee law calls for a steadily increasing test score that third graders must achieve in order to be promoted to fourth grade. For 2013–14—the first year of implementation—the State Board of Education was required to set an initial promotional standard somewhere above the limited achievement level on the third grade ELA exam. Each year thereafter, statute directs the Board to increase that bar until it reaches the minimum proficiency score for the 2024–25 school year (a date established just last year by HB 82). The achievement levels and corresponding scale score ranges on the state’s third grade ELA exam are displayed below.

The Board has used its discretion to take only small steps to lift the bar. By 2018–19, the promotional standard was just five points above the limited level (677) and the current score is 683, slightly less than halfway between basic and proficient. Due to covid-related legislation, the retention requirement has been completely waived for 2019–20, 2020–21, and 2021–22. The slow phase-in—not to mention the waivers—has spared schools from having to intervene in more children’s educations. But it also means that the Board will need to significantly raise the promotional score over the next two years to match the proficiency standard (700) by 2024.

In my view, the absurdly long phase-in period was poor policy design. It’s made the promotional standard a moving target each year, and has opened annual debates over where the “cut score” should be set. While the phase-in is scheduled to finally end, the looming proficiency requirement could instigate outcries from schools that, due to the Covid-slide, face the prospect of retaining a quarter to more than half of their third graders. On last year’s state ELA tests, for example, more than 75 percent of third graders in Cleveland, Columbus, Dayton, Toledo, and Youngstown did not reach proficiency. Offering high-quality interventions to so many students would be a Herculean job—likely amounting to adding another grade level.

While proficiency is a clear and admirable standard, retention should probably focus on children with the greatest reading deficiencies. Moving the bar to proficient could result in schools spreading intervention resources too thin, and it also risks a bitter debate that could ramp up pressure to eliminate the retention requirement altogether. One possible option is to permanently set a promotional test score of 683—the present cut off—a standard that would still ensure that struggling readers are identified and given extra supports.

2. Tighten the exemptions from the promotional requirements. Under current law, many special education and English language learners are exempt from the state’s retention requirements. Of course, there are certainly cases where an exception is warranted—for instance, a child with severe cognitive disabilities—but the loophole seems too large. In 2018–19, 6.2 percent of third graders statewide were exempt, and in seventy-eight Ohio districts, more than 10 percent were exempt. In a handful of districts, more than 20 percent of their third graders were exempt from promotional requirements, suggesting that some children with mild disabilities such as dyslexia were excused.

These excusals are troubling, as children with special needs or from immigrant families need to be able to read just the same as their peers. Some may believe that it’s too harsh to expect children with disabilities, however moderate, to reach comparable academic standards. But that’s not the view of most experts. A recent Ohio Department of Education report, informed by educators and parents, notes that, “Except for a very small number, students with disabilities are as cognitively able as their nondisabled peers.” The National Center for Learning Disabilities and Learning Disabilities Association writes, “Students with disabilities, as a whole, should not be automatically exempted from these [reading retention] policies.” As for English language learners, there is evidence that retention yields academic benefits, especially for immigrant children. In sum, Ohio lawmakers should carefully review and potentially narrow the exemption provisions to ensure that special-needs children are not being written off and instead receive the helps and supports they need.

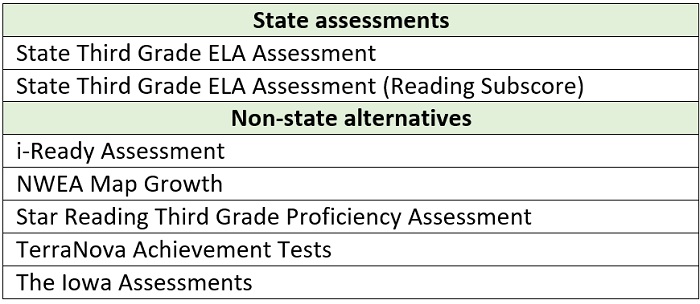

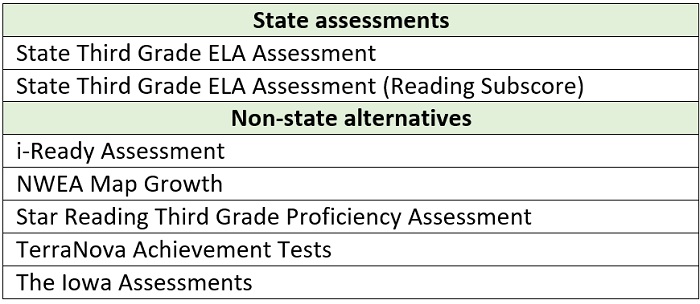

3. Address alternative assessments. Third graders, as they should, have multiple opportunities to meet the promotional standard on their state ELA exam—whether via mandatory fall or spring assessments or an optional summer administration. But state law also allows promotion if third graders demonstrate an “acceptable level of performance” on a non-state, alternative assessment. Districts may choose to administer (or not) these alternatives, and they may be given up to three times per year. For the current year, ODE has approved six alternatives, of which five are vendor assessments. A sixth option, technically an alternative, is the reading section of the state’s third grade ELA exam which also includes writing. The table below displays the testing alternatives.

In 2018–19, 3.3 percent of Ohio third graders—just shy of the 5.0 retention rate—were promoted based on an alternative, having fallen short of the promotional standards on their state ELA exams. Whether these students have the same reading capabilities as those who achieved the promotional score on the state test is an open question. How exactly does the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) determine the “acceptable levels” of performance on these alternatives? Does a passing score on the Star test mean the same thing as a passing score on the Ohio state test? And what indeed are the pass rates on the alternatives, and how do they compare to state exams?

State lawmakers have a few options to deal with these uncertainties. The most straightforward approach is to simply eliminate them, thus enforcing a true statewide standard for promotion. Absent that, they could continue to permit alternative assessments but add language requiring ODE to demonstrate that promotional scores on the alternatives are equivalent to the state exam standard (akin to an ACT and SAT “concordance” analysis). Lastly, also as a matter of transparency, ODE should release data by district and school on the percentage of students meeting promotional standards via alternatives, something it does not currently do. So long as alternatives remain available, this information should be made public. Doing so might help to flag any school that is using them to circumvent state standards, a possibility if some tests are less rigorous than the state exam.

* * *

Teaching children to read is one of the basic responsibilities of schools, and state policymakers have a duty to ensure that this is happening in Ohio’s schools. The Third Grade Reading Guarantee has the right aims and includes important policies such as mandatory retention for children having difficulty reading. With some tweaks to the policy details, legislators would further strengthen the policy and ensure that all children are on track to becoming good readers.

With only minor exceptions at the very top and bottom of the overall scale, these ranges have been the same between 2015–16, the first year Ohio implemented its current state tests, and 2021–22.