When Governor DeWine announced that Ohio schools would remain closed for the rest of the 2019–20 school year, many students and parents immediately began to wonder what school will look like in the fall. Given the unpredictably of COVID-19, it’s impossible to know. But one thing’s for sure: When schools do reopen, teachers and students are going to have a lot of work ahead of them. Here are four areas where lawmakers, school administrators, and teachers will need to adjust in order to address the fallout of coronavirus closures.

Data on student growth and achievement

It’s no secret that the school closures brought about by the pandemic are likely to have a serious impact on student learning. Three recent analyses have predicted poor outcomes for reading and math achievement and growth, with particularly devastating impacts for low-income students and students with disabilities.

Just how large Ohio’s learning losses will be is not yet known. In late March, Governor DeWine signed legislation waiving state testing requirements for the 2019–20 school year. This was the right call, but it also means we have no idea how much kids learned this past year. When schools reopen, one of the first orders of business should be determining where students are academically. That could mean administering state tests when students return in August or September. But given that state tests have historically been used to gauge achievement and growth on a broad scale, and are not typically used to identify the immediate needs of individual students, it might be better to encourage districts to use interim and diagnostic assessments. Those exams often have a faster turnaround time, so teachers won’t have to wait for state testing results to begin addressing their students’ academic needs.

Testing is only one piece of the puzzle, though. As a recent piece by Laura Slover in The 74 points out, data aren’t useful without “analysis and subsequent adjustments.” Once schools have identified learning gaps and losses, the next step will be to use those data to plan for and adjust to student needs. “Data-driven instruction” can no longer be just a buzzword. Next year, schools need to make it a guiding principle.

School funding

Another obvious impact of the pandemic is the financial toll. As Fordham fellow Dale Chu recently wrote, schools across the nation are facing a “triple threat” of financial fallout. First, students who have fallen behind academically thanks to the closures will need extra help, which can cost extra money. Second, declining state revenues will result in historic budget cuts. And third, districts are likely to face rising costs in other areas, such as pensions.

Ohio is no exception. School finance in the Buckeye State is about to look very different than it did at the beginning of the year. The Cupp-Patterson plan to revise the state funding formula is probably off the table for at least the next few years. Funding that could be considered supplemental—such as student wellness funds, performance incentives, and reimbursement programs—could disappear under future budget proposals. Ohio elementary and secondary schools are set to receive hundreds of millions in federal funding, and future relief bills will hopefully provide more. But even with this infusion of cash, schools of all types are in for a rough few years.

Over the next few months, state lawmakers and district leaders would be wise to consider the recommendations of my colleague Aaron Churchill. They include targeting funds to help the state’s most disadvantaged students, restarting the school funding formula, and providing additional flexibility around how schools can spend funds.

Instructional time

School leaders and advocates will also need to rethink how long and how often kids attend school. Prior to pandemic-related closures, research indicated that increased instructional time could lessen or eliminate achievement gaps. Many low-performing schools—district and charter—opted for extended days and extended years as a means of providing extra instruction and remediation for students who were academically behind their peers.

Now, in the wake of widespread coronavirus closures, extended time may no longer be an intervention that’s reserved only for chronically underperforming schools. All schools will need to consider extending school days and years to make up for the learning losses brought about by COVID-19, even if those extensions only last for a year or two. Summer school may or may not be off the table for 2020—it all depends on a virus that’s shown itself to be very unpredictable—but districts should consider planning intensive summer school programs for 2021. Beefed-up afterschool or weekend programs are worthy of consideration. It may also be time to finally rethink grade-level progressions, and allow students to advance based on what they know rather than how long they’ve been sitting at a desk.

Obviously, there are pros, cons, and complications to each of these options. Not one of them is a silver bullet. But school leaders and advocates should be ready to have serious conversations about instructional time over the next few months to mitigate coronavirus learning loss.

Innovation and improvement

It seems odd to discuss innovation and school improvement when educators and administrators are still trying to adjust to unforeseen circumstances. But all this change is exposing cracks in the education system, and those cracks are presenting opportunities for growth. As schools reopen and educators start evaluating the best ways to get students back on track, it’s important to take advantage of the lessons we’ve learned during these unprecedented times.

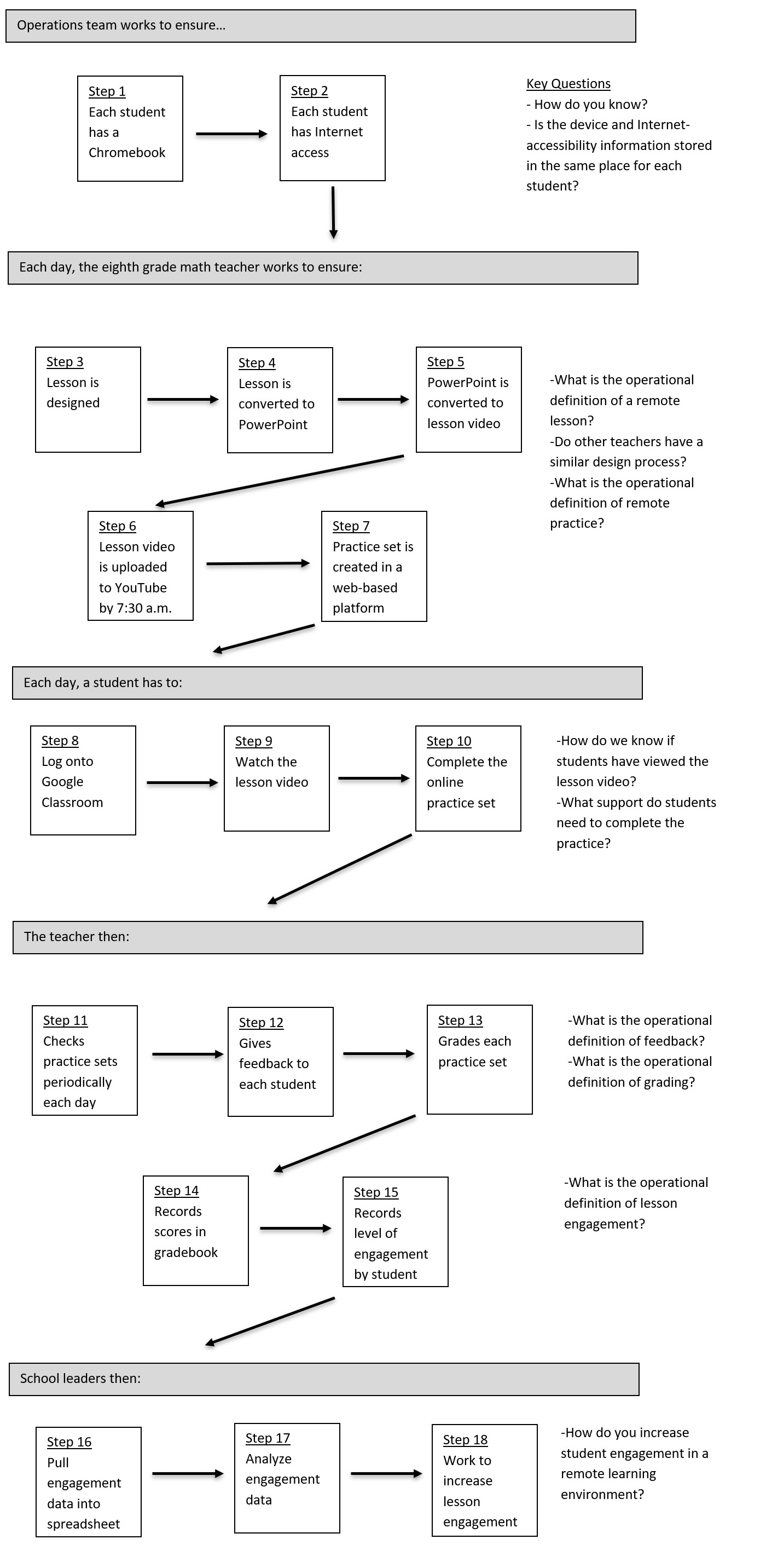

For starters, it’s critical for Ohio to start gathering information from students, parents, and teachers about how distance learning implementation worked on the ground. This feedback will be instrumental in planning for future remote learning efforts, should schools need to close again in the fall due to the virus. Identifying best practices and working to refine them could also help address issues that schools have when they’re operating normally, such as how to prevent learning loss during snow days or student suspensions. Online platforms that schools found particularly helpful during the shutdowns could be leveraged into blended learning models or to provide remediation and enrichment for individual students who need it. And the gaps this crisis has revealed in access to Wi-Fi and internet-enabled devices shouldn’t cease to matter once schools are back in session. In our increasingly digital world, all students need internet access—which means expansion efforts must continue.

***

There’s no doubt that the next few years are going to be hard. Funding shortfalls and learning losses are steep mountains to climb, and it’s going to take a lot of work on the part of teachers, parents, and communities to help kids thrive in the midst of adversity. But if lawmakers and leaders focus on addressing the four issues outlined above, climbing those mountains will be more than possible.