Universal ACT and SAT participation is a matter of equal opportunity

Over the past few years, education groups have pushed the General Assembly to walk back the state policy that requires all high school juniors to take the ACT or SAT exam.

Over the past few years, education groups have pushed the General Assembly to walk back the state policy that requires all high school juniors to take the ACT or SAT exam.

Over the past few years, education groups have pushed the General Assembly to walk back the state policy that requires all high school juniors to take the ACT or SAT exam. Earlier this year, House legislators introduced a bill that would eliminate this requirement (House Bill 82). While the lower chamber’s version of the state budget doesn’t go quite as far, it weakens the mandate by allowing students to bypass these exams with parent permission.

Opponents of universal testing have argued that not every student needs to take college entrance exams. They’re right in the sense that many young people can achieve their professional goals through technical training or an associate degree. But they are wrong to deny all students the opportunity to pursue admission into four-year universities. For many qualified students, a test-optional policy means they’ll go unidentified as a competitive candidate in the college admissions process, forestalling what could be attractive options for their futures. As we’ll see, students from groups that have been underrepresented in higher education are more likely to slip through the cracks when no one requires their participation.

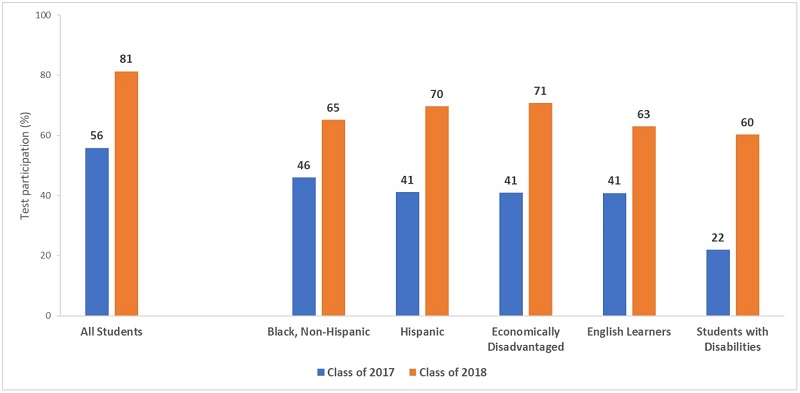

Because Ohio only recently moved to universal testing, we can predict what is likely to occur if legislators were to reverse course. Figure 1 shows ACT participation rates for the class of 2017, the last cohort that was not subject to the exam requirement. The statewide participation rate was 56 percent, but we notice substantially lower rates for disadvantaged groups. Less than half of Ohio’s Black, Hispanic, economically disadvantaged, and English learners took the ACT. Not even a quarter of students with disabilities decided to take the test. In sum, a troubling “opportunity gap” emerges when test-taking is not required by the state.

The gap, however, narrowed when participation became mandatory for the class of 2018. ACT participation rates rose across the board, with 81 percent of Ohio students taking the test. (SAT test-taking and dropouts explain why the rate was not 100 percent.) While less advantaged groups still registered lower participation rates, more than three in five Black, Hispanic, economically disadvantaged, and English learners took the ACT. Students with disabilities experienced the largest jump in participation—from just 22 percent of the class of 2017 to 60 percent of the class of 2018.

Figure 1: ACT participation rates for the classes of 2017 and 2018, selected student groups

Note: Though fewer students take the SAT in Ohio, test participation rates on that exam also rose. For all students, SAT participation went from 6.5 percent for the class of 2017 to 12.0 percent for the class of 2018. These participation rates would include dropouts who did not take the ACT or SAT, likely explaining a less than 100 percent rate for the class of 2018.

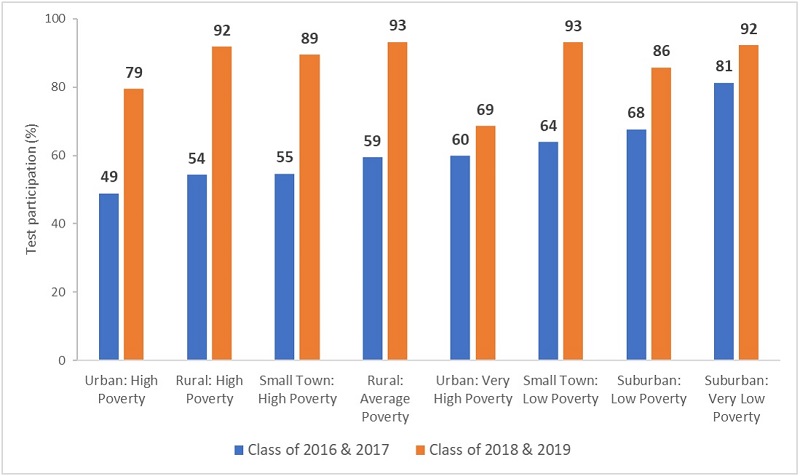

The next figure shows the changes in test-participation rates across districts of varying geographic and socio-economic typologies. What’s interesting here is that poor rural and small town districts had relatively low participation rates when Ohio allowed testing to be optional. For example, just 54 percent of students in the classes of 2016 and 2017 from rural, high-poverty districts took the ACT when the exams were optional. The picture dramatically changed with the statewide testing requirement coming into effect. Now more than 90 percent of students in rural districts take the ACT.

Figure 2: ACT participation rates for the classes of 2016–17 and 2018–19, by district typology

Note: ODE reports district-level test participation data that are combined across two graduating classes. The relatively small increase in the Urban: Very High Poverty typology is likely due to sizeable numbers of students taking the SAT in those districts. The chart displays an average participation rate for each typology that is weighted by the number of students in a district’s graduating class.

Some may argue that these “new” test takers are academically middling students who aren’t likely to succeed in higher education. The legislative sponsors of HB 82 seemed to suggest as much when they stated their belief that some students “do not take the test seriously.” In some circumstances, requiring students to sit for the exam may indeed be a questionable use of a time. But it’s not always the case. A Virginia analysis, for instance, found that a quarter of the students who skipped their college exams would have likely achieved competitive scores; a similar finding emerged when analysts looked at Michigan data. The latter analysis found that tens of thousands of low-income but academically talented students had not been taking the ACT or SAT. For these college-prepared students, it’s well worth the effort to ensure that they actually take these exams.

Unfortunately, no comparable research has been undertaken in Ohio. Thus, we don’t know the performance of students who did not take college exams prior to the statewide requirement. While a precise analysis would require student data, there are indications that a number of high-ability students skipped these college exams under a test-optional policy. Some districts, for example, posted proficiency rates that were significantly higher than their ACT participation rates. In Lorain School District, for example, just 16 percent of its classes of 2016 and 2017 took the ACT, but roughly double that number of students passed their high school EOCs in 2015–16. The same phenomenon can be seen in a number of largely rural and small-town districts where ACT participation rates were in the 40’s and 50’s, while proficiency rates were in the 60’s and 70’s.

As a matter of equal opportunity, all students should be given at least one shot to take college entrance exams that can open a lifetime of opportunity. A universal participation requirement ensures that this actually happens. Under such a policy, talented students don’t get shut out of colleges just because they didn’t realize the importance of taking these exams. Rather than trying to scrap this policy, lawmakers should take pride in the fact that they guarantee that every Ohio student has a chance to pursue higher education.

As Ohio’s General Assembly continues working on the biennial state budget, policymakers have the unique chance to pursue meaningful education reform for Ohio’s K–12 students. Given the dark rain clouds of the past fourteen months, we are all grateful to see a silver lining emerging. Ohio is currently considering the largest school funding overhaul in at least twenty years—the best opportunity in a generation to make a difference for Ohio schoolchildren and their families.

The pandemic has disrupted elementary and secondary education like nothing else in our lifetimes. Schools have been shuttered, students sent home to learn in online “classrooms,” and curricula rewritten to cope with new realities. Public school administrators grappled with the risks and complexities of reopening. Many parents have wondered how well their children were really learning in remote environments. Others didn’t have to wonder; they saw firsthand that their children were not thriving online. And parents across the Buckeye State have been forced to reconsider the pros and cons of their local public schools in ways they had never done before.

In fact, an interesting recent poll shows that 66 percent of parents with a child at home agreed that at least a portion of funding should follow students in what is sometimes called the “backpack” model.

Enter education savings accounts—often referred to by their acronym ESAs—which satisfactorily address the sentiment of those same 66 percent of parents and the unique challenges facing families in the wake of the pandemic.

As the name suggests, ESAs are special savings accounts funded with state education dollars, which are designated for families to spend on education expenses. ESA funds can be used to pay for a wide variety of educational products and services, including laptop computers and other necessary technology for distance-learning, software, online courses, private tutoring, other support services, and curriculum enhancements.

ESAs also give parents greater control over their children’s education by directly giving them additional financial resources to help pay for more personalized learning tailored for each student’s individual educational needs.

No school or system, whether public or private, has a proven silver bullet strategy for educating students during a pandemic. And no one-size-fits-all model will properly educate every child—whether there is a pandemic or not. Unfortunately, the current proposals being considered by our elected officials still fund our public school systems rather than the students they are tasked with teaching.

ESAs are more flexible than Ohio’s existing voucher programs because ESAs would allow parents to pay for more than just tuition. Rather than continue funding school systems, Ohio—like its families—should reevaluate its approach to education and education-related spending to accommodate present and future realities.

Even before the pandemic interrupted two academic years, the Nation’s Report Card warned that African American and Hispanic students, as well as students in low-income households, were suffering from persistent academic achievement gaps. The pandemic is unlikely to have closed those gaps.

Indeed, more students than we would like to admit have probably slipped through the educational cracks over the last year.

Through ESAs, Ohio could help students at every income level, of every race, and in every neighborhood of the state pay for learning that is right for them. Nine other states have pioneered ESA programs tailored to meet their students’ needs. Ohio is falling behind and should join the growing movement toward funding the unique needs of students rather than one-size-fits-all business as usual.

In the wake of this devastating once-in-a-lifetime pandemic, this biennial budget offers Ohio’s General Assembly a corresponding once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. We must reassess K–12 education and carefully design and implement an ESA program, with guardrails to ensure that funds are easy to access and appropriately spent, but without onerous burdens or bureaucratic meddling. Ohio should take a student-first approach in order to significantly improve education outcomes for students in every corner of the state. Sometimes, the hardest thing is to recognize the silver lining when it appears. The General Assembly should act now—for the sake of all Ohio students.

Robert Alt is President and Chief Executive Officer of The Buckeye Institute.

In February, Governor DeWine asked all public schools to create plans designed to address the learning loss caused by pandemic-related school closures. The governor requested that schools publish them by April 1, and the Ohio Department of Education has posted them on its website to make it easier for parents and stakeholders to find them.

The importance of summer programming cannot be overstated. Although education researchers are still working to pinpoint the breadth and depth of learning loss, there’s little doubt that it has occurred and still is. Offering some type of extended learning opportunity to students who need it is crucial. This is especially true in districts with large populations of low-income students and students of color, communities that were hit especially hard by the pandemic. In Ohio, there are several districts that fit that description, including the state’s largest district, Columbus City Schools (CCS). CCS has an enrollment of nearly 50,000 students, most of whom are economically disadvantaged and students of color.

So what does CCS plan to offer students? The answer is the 2021 Summer Experience, a program that aims to “provide enriching experiences for all students in PreK through 12th grade.” The initiative begins June 15 and continues through July 22, with students attending Monday through Thursday from 8:00 am to 1:00 pm. Programming will be housed in thirteen elementary schools, ten middle schools, and five high schools spread throughout the city. Transportation will be provided, as well as breakfast and lunch. The registration deadline is June 1.

As far as eligibility goes, the district appears to be trying to reach as many students as possible. There are some programs—like “enrichment extensions” or AP Bootcamp—that are capped at a certain number of seats and don’t last all summer, likely because they require staff with specialized training or knowledge. Generally speaking, though, any student who attends a district school can enroll in their grade-specific program. Summer Experience, much to CCS’s credit, is also open to students who reside in the district but don’t attend district schools. That means charter and private school students can also register to participate, free of charge.

But what, exactly, are students signing up for? Well, that largely depends on grade level. There aren’t a ton of details—we don’t know, for instance, what a daily schedule would look like for any given student—but here’s a brief overview of what’s available.

Elementary

Students in grades K–5 can register to participate in “mini camps” that are modeled after summer camp experiences but are aimed at “strengthening academic skills, leadership, and social-emotional learning.” All thirteen of the elementary sites will offer the same programming, and students are free to attend whichever site they choose, which should give parents some flexibility. For instance, instead of being required to send their child to the school closest to their home, parents could opt to enroll their child at a building that’s closer to a caregiver’s home, daycare, or a place of employment.

For students in grades K–2, camps have been “inspired” by programming offered by the Franklin Park Conservatory. Students will have a chance to interact with specialists from the Conservatory both inside and outside the classroom and will take a field trip to the Children’s Garden. Each of the six weeks is devoted to a camp with a distinct theme, such as Jurassic Franklin Park, Pirate Palooza, and Summer Science Nature Detective. (See here for information on programming available for rising kindergarteners.) Camps for students in grades 3–5, meanwhile, have been modeled on COSI programming and will provide students with an opportunity to visit the science museum. These camps will also have distinct themes, such as Gadgets to Go, Mission to Mars, and Superhero Science.

Middle school

Unlike their younger peers, middle schoolers won’t be attending a differently themed mini-camp each week. Instead, each school site will offer its own themed camp for the duration of the summer. Programming for these camps was designed by CCS staff and teachers in collaboration with the PAST Foundation, and will “use design-thinking strategies to solve real-world problems.” Students can choose to attend whichever camp interests them, with options including aviation, cyber security, the business side of eSports and gaming, fashion in STEM, food science, medicine, robotics, and 3D modeling. A small number of seats will also be available for middle schoolers interested in two-week long “enrichment extensions” offered at Spruce Run—the district’s environmental education center—with transportation provided. There are five options, including a Survivors Camp where students will read Hatchet by Gary Paulson and work on mastering survival skills.

High school

At the secondary level, Summer Experience offerings get a little more complex in order to reflect the broad needs of high schoolers. There are six options:

***

It’s hard to tell based on the limited information that’s available whether these programs will help students regain academic ground they lost over the last year. But to be fair, it would be impossible to judge any new program that’s been built from scratch in a matter of months to address fallout from a never-before-seen pandemic. There are several aspects of Summer Experience that seem promising, such as STEM-focused camps for third through fifth graders, and the wide variety of themed camps available for middle schoolers. But there are also aspects of the plan that should give parents and advocates pause. For instance, offering online credit recovery programs is probably cheap and easy. But after a year of virtual learning where many students struggled because their classes were online, having them take yet another online class seems unfair.

Overall, though, the extended learning plan put forth by CCS deserves praise. Like the summer offerings at affluent private schools and high-performing suburban districts, the CCS Summer Experience reflects an intentional effort by district leaders and teachers to offer students engaging summer programming that will improve hard and soft skills. The district has made that programming available to all of Columbus’s children, even if they don’t attend district schools. And in every grade band, the district has chosen to collaborate with at least one well-respected community partner in ways that will have a direct impact on students. There’s always room for improvement and growth, but CCS deserves a whole lot of kudos for this plan.

ExcelinEd, a national education group, recently released a paper revealing large shortfalls in facility funding for Ohio’s public charter schools. According to its analysis, the state currently meets just 18 percent of brick-and-mortar charter facility needs, with the rest being covered through general operating revenues. Insufficient facility resources squeeze charters’ instructional budgets, hampering efforts to pay more competitive teacher salaries or offer extra pupil supports. Meager facility supports are also a major roadblock for high-performing schools seeking to expand and serve more students.

Adequately meeting charter facility needs remains a tall order for Ohio. The good news, however, is that state legislators have various policy levers at hand to accomplish this task. Foremost, they ought to boost the state’s modest $250 per pupil facility allowance to an amount that is closer to the actual cost of operating a school building (about $1,500 per pupil). They should also restart the charter school facility grant program or give charters access to the state’s main school construction program. But lawmakers should also consider innovative ideas that other states have pioneered to better support facility needs. Consider three policies that Ohio should adopt.

Indiana: Enabling charter to access surplus buildings at minimal cost

Due to demographic shifts and the choices of Ohio parents, enrollment in many school districts has steadily waned. This suggests a supply of empty (or near empty) buildings that could be put to good use by charter schools looking for space. To its credit, Ohio has long had a “right of first refusal” law that requires districts to sell or lease unused buildings to charters before they offer them to other entities. However, the statute allows districts to sell these properties at market value. At first blush, this doesn’t sound so unreasonable. But the market rate may be too steep for charters that not only have to cover the purchase price, but may also need to undertake renovations to upgrade the facility. This might explain why Cleveland charters recently passed on a number of district-owned buildings that are now being marketed to private developers.

In contrast to Ohio, Indiana requires districts to offer charters unused facilities for sale or lease for $1. Although that might sound extreme, it’s justifiable on policy grounds. For one, taxpayers have already paid for the building and they shouldn’t have to pay for it twice when a charter buys it. Of course, it also gives charter schools far more access to buildings that were purposefully designed for instruction. While such a nominal cost may be a tough sell politically, Ohio legislators should reconsider whether the market value is the right price point for unused facilities. One option would require districts to offer the building at a fraction of the officially appraised value—the value as a school facility, not its potential commercial worth. Such a change would make unused facilities more affordable to charters.

Arizona: Reducing the cost of financing through credit enhancement

One challenge for charter schools has been access to affordable loans. Unlike school districts, charters can be closed due to academic underperformance or low enrollment, creating an inherent risk to lenders. A number of states have recognized this challenge, and have stepped up to support schools seeking to borrow at more favorable interest rates. Arizona’s “credit enhancement” program is one such example. The Grand Canyon State guarantees certain bonds—that is, pays the outstanding principal and interest in the case of default—that are issued on behalf of charter schools. This government backing can significantly reduce charters’ debt servicing costs as the state’s superior credit rating substitutes for the one they would’ve received without enhancement. Arizona’s program is overseen by a board that approves schools’ applications for credit enhancement; only schools meeting certain guidelines are eligible. A debt reserve is established to pay a lender in the case of default—there hasn’t been one in the program’s four years—and is funded through a state appropriation and nominal fees from participating schools. Ohio does not have a credit enhancement program for charters, but legislators should strongly consider creating one. It would allow charters to undertake larger capital projects, such as school construction or renovations, while significantly reducing interest payments. A similar program in Colorado, for example, is estimated to have saved charters $100 million in financing costs.

New Mexico and Colorado: Including charters in local facility-related levies

With only a few exceptions, Ohio charters haven’t received a nickel of the billions raised through local taxes, including funds raised for buildings. This denies charters another avenue to meet their facility needs. A handful of states have required districts to provide charters with more access to local dollars raised specifically for construction and maintenance. New Mexico, for example, simply requires districts to provide charters with a proportional share of local facility funds. This is an approach that Ohio should consider. Another possibility is the Colorado model. It takes a more community-driven approach that strongly encourages charter inclusion in local levies but does not mandate it. The law requires districts to include charters in facility planning and on levy committees, and Colorado charters may seek funding for their facility needs on the ballot measure. However, districts may deny their request, so there is no guarantee that charters will be included in the levy.

* * *

Ohio has a long way to go to fully support the facility needs of public charter schools. Fortunately, state leaders don’t need to reinvent the wheel to achieve this goal. They can look to other states—those “laboratories of democracy”—that are creatively helping charters build classroom facilities that will serve generations of students.

It’s rare for policies that are proposed in the state budget to sail untouched from the governor’s office through the House and to the Senate—especially if they’ll have a significant impact on the status quo. But that’s exactly what seems to be happening with the governor’s computer science proposals, which were recently passed by the House with virtually no changes and are now before the Senate.

Assuming these provisions move just as smoothly through the upper chamber, what would they mean for Ohio? Here’s a brief overview of three significant aspects.

Establishing a state committee

The House-approved budget calls for the Ohio Department of Education (ODE), in conjunction with the Ohio Department of Higher Education, to establish a committee tasked with developing a plan for implementing computer science education statewide. Both the state superintendent and the chancellor of higher education (or their designees) must be members, and they are responsible for appointing the remaining participants. The budget language doesn’t specify an official number of seats, which means the committee can be as large as the superintendent and chancellor want it to be. It does stipulate, however, that it must include teachers, representatives from the career and technical education sector, institutes of higher education, businesses, and state and national computer science organizations.

Creating a state plan

Once committee members have been appointed, they will be responsible for developing a plan for implementing computer science education at the primary and secondary level. The plan must be completed no later than one year after the bill goes into effect, and must be made public via ODE’s website.

The list of topics that the committee is charged with considering when drafting the plan includes:

Although these topics aren’t required to be part of the committee’s plan, some of them definitely should be. For example, the committee would be wise to research and then actually address how the state can establish a sustainable pipeline of well-trained teachers in this field. Computer science education is growing in popularity, but it’s still uncommon enough at the primary and secondary level that there may not be enough teachers to go around. A shortage would be especially likely during the first few years of a statewide implementation effort, when all of Ohio’s schools are suddenly scrambling to find certified teachers.

The bill also outlines two things that the plan must include. First, it has to contain “an examination of the challenges that prevent districts from offering computer science courses.” This is critical, especially given the course offering requirement discussed below. It’s important to note, though, that the legislative language only mandates an examination; actual solutions aren’t required. Second, ODE must collect data on districts’ computer science offerings, including course names and whether they are based on the state’s standards and model curriculum. The state must then post these data on its website.

Making computer science courses available for students in traditional public schools

This proposal is the most controversial, as it requires traditional public schools to offer students the option of enrolling in a computer science class. This could mean a course offered by the district (perhaps one of the AP Computer Science courses), an integrated course (a general education class that incorporates computer science principles) also taught by the district, or an approved online class offered by an outside educational provider.

To assist with the online option, the bill requires ODE to establish a statewide program aimed at high schoolers. Under the program, the department will solicit and review proposals from education providers that are interested in offering courses to districts. The bill outlines a few conditions for approval—proposed courses must be rigorous, aligned to state standards and the model curriculum, and credit-bearing—as well as some stipulations for how providers receive payment for their services. For the most part, though, the details of program implementation have been left to ODE.

There are two additional provisions worth noting. First, although it’s up to districts which courses and delivery methods they offer, there are some hard deadlines they must meet. Students in grades 11–12 must have the option to enroll in a course during the 2022–23 school year, and students in grades 9–10 must be able to enroll during the following year. By 2024–25, all students in grades K–12 should have the option to enroll in an age-appropriate course. That’s a tall order, and it doesn’t give schools much time to get their ducks in a row, especially given the potential shortage of certified teachers. The online course options approved by the state will likely be critical to ensuring access for all Ohio students by these deadlines.

Second, the bill allows local boards of education to submit a request to the state superintendent asking for permission to waive course offering requirements for students enrolled in a particular building. Approved waivers can last no longer than five years, but districts are permitted to apply for renewal. It’s unclear why this provision was included, unless it was to forestall some predicted pushback. It’s similarly unclear whether the provision was intended for certain schools and, if so, which ones. One thing’s for sure, though: Without more clarity from lawmakers, underserved and disadvantaged students could be those who end up being denied access. And that’s not OK.

***

All things considered, the budget’s take on computer science is a mixed bag. Establishing a diverse committee to create a statewide plan is a smart move, and the topics that the committee must consider are all worthy of attention. But the requirement that traditional public schools offer computer science courses to all students within the next few years is far more complicated. The proposal is well-intentioned. In an increasingly digital world, students would benefit from computer science content. But without answering some of the more pressing concerns that the bill itself identifies—such as course rigor and teacher talent—students may not see the benefit policymakers intend.

Since 1997, the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) has tested students around the globe every three years to determine the educational status of fifteen-year-old students in dozens of countries and economic regions that are part of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). PISA assesses not only the core subjects of reading, math, and science, but also areas such as creative problem solving and “global competence.” In that time, PISA has become an international reference for comparing quality, equity, and efficiency in learning outcomes within and across countries. It has also provided policymakers with invaluable statistical evidence on a wide range of education issues.

For the 2018 administration of the test, PISA included a “growth mindset” instrument. Students who have this mindset believe that intelligence is malleable based on things like effort and the willingness to explore new ways to learn, as opposed to being fixed. PISA researchers have long sought to debunk this fixed mindset, but this was the first systematic attempt to study it at scale. And the scale was pretty huge—surveying some 600,000 students in seventy-eight countries and economies across the world.

The study found that almost two out of three students who participated in PISA demonstrated a growth mindset. And that after controlling for students’ and schools’ socioeconomic differences, students with a strong growth mindset scored significantly higher on all subjects—31.5 points higher in reading on a 100 point scale, 27 points in science, and 23 points in math—compared with students who believed their intelligence was fixed. Across thirty-nine countries and economies, more girls had a growth mindset than boys, and girls got a larger boost in academic performance from having it.

However, the cultural differences between some countries were stark. In Estonia, Denmark, and Germany, for example, at least three-quarters of students reported having a growth mindset. And Estonia topped OECD countries on PISA overall in 2018. The performance gaps in reading were also the widest in New Zealand, Australia, and the United States, where 70 percent of students demonstrated a growth mindset. Students with a growth mindset in these countries scored around 60 points higher in reading than their counterparts. Meanwhile, more than two-thirds of students in the Philippines, Panama, Indonesia, Kosovo, and the Republic of North Macedonia agreed with the fixed mindset statement “Your intelligence is something about you that you can’t change very much.”

But that pattern was not universal. In a number of East Asian countries—such as Japan, Korea, and the Macao economic region of China—growth mindsets were positively associated with academic performance, but far more weakly than in the average OECD country. By contrast, growth mindsets and reading performance were entirely unrelated in Hong Kong, and even negatively associated in the so-called B-S-J-Z economic region of China.

The study also discussed three instructional practices related to students’ growth mindsets. Those who perceived that their teachers adapted lessons to the class’s needs and knowledge were 3.5 percentage points more likely to have a growth mindset than their peers. Teachers who reported giving feedback to students—specifically regarding their strengths and areas of possible improvement—exhibited a modest positive effect on moderately good readers in terms of instilling a growth mindset in them. But they had no effect on top readers, and their lowest-tier readers were actually more likely to have a fixed and negative mindset about their reading ability.

Teacher support proved the most closely connected to both students’ mindsets and their performance. Students with supportive teachers—that is, those who show interest in every student learning and a willingness to provide extra help and explanation until a student understands—were 4 percentage points more likely to have a growth mindset than those without a supportive instructor. In the United States, for example, students with a growth mindset outperformed those with a fixed mindset by 48 points in reading when they had low teacher support, but by 72 points when they had supportive teachers.

The picture drawn by these data is important and intriguing, but much more is required. Could systematic efforts to help build growth mindsets in students—especially via specific teaching practices—help increase student achievement? It’s an important question, with most OECD countries having seen virtually no improvement in the performance of their students since PISA was first conducted in 2000. PISA has big plans for subsequent research on the topic—as soon as Covid-delayed testing resumes in 2022.

SOURCE: “Sky’s the limit: Growth mindset, students, and schools in PISA,” OECD (April 2021).

NOTE: Today, the Senate Primary and Secondary Education Committee heard testimony on HB 110, the state’s next biennial budget. Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Advocacy presented interested party testimony on a number of education provisions. These are his written remarks.

Thank you, Chair Brenner, Vice Chair Blessing, Ranking Member Fedor, and Senate Primary and Secondary Education Committee members for giving me the opportunity today to provide testimony on this year’s biennial budget bill—House Bill 110.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy and Advocacy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a charter school sponsor.

While it’s always the mechanism by which we fund schools, the state budget isn’t always about school funding. This year, it is. HB 110 includes the much discussed, self-described “Fair School Funding Plan.” This committee has already heard substantial, and often highly technical, testimony on the House’s school funding proposal. My remarks today will focus on a few key aspects of the plan and highlight some of the things you might not have heard from prior witnesses. In addition to school funding testimony, I’ll touch on a few policy issues impacted by HB 110.

School Funding Changes

The Fordham Institute has long advocated for reforms that put Ohio students and parents at the center of school funding policy. It’s with that principle in mind that we present these comments on the proposed funding formula.

Education Policy Changes

Beyond the funding formula, there are some policy changes that merit discussion.

The budget process is never easy, but it’s really important. Thank you for all that you do to ensure that all Ohio families have access to great schools to meet their unique educational needs.