Using course grades for graduation doesn’t advance equity or excellence

Last week, the Ohio House passed legislation (HB 67) that addressed graduation requirements and a few other issues in K–12 education.

Last week, the Ohio House passed legislation (HB 67) that addressed graduation requirements and a few other issues in K–12 education.

Last week, the Ohio House passed legislation (HB 67) that addressed graduation requirements and a few other issues in K–12 education. The bill, which is currently being heard in the Senate, gives schools temporary authority to determine whether seniors may receive high school diplomas. This extends an emergency policy enacted last year for the class of 2020 that waived standard graduation requirements because of the pandemic.

While giving seniors a reprieve may be sensible, HB 67 goes a step further by allowing any high school student—this year’s freshman, sophomores, and juniors—to substitute course grades for their end-of-course (EOC) exam scores taken this year. If this sounds familiar, it is. Last June, legislators enacted a bill that allowed high school students whose EOC exams were cancelled to substitute course grades in that subject for the purposes of graduation. For instance, any grade of “C” or above was deemed equivalent to a “competency” score on the key EOCs that students need to achieve to graduate (algebra I and English II). This substitution policy would continue under HB 67.

All this was an acceptable Band-Aid last year when state tests were not given. But it’s nonsense to prolong this supposedly temporary policy. First off, schools will soon be administering state exams, including EOCs, so there’s no need to find a substitute for cancelled exams this year. Moreover, maintaining this workaround only reinforces a misguided notion that course grades are appropriate substitutes for exam scores.

On this blog, we’ve discussed at great length the problems of using course grades or GPAs to meet graduation requirements. Just a few days ago, my colleague Jessica Poiner rightly blasted inappropriate provisions in the budget bill that would permanently allow course grades to substitute for strong EOC scores as a demonstration of mastery in biology, U.S. history, and American government. Why are we so adamant about not allowing course grades to stand in the place of exams? In briefest form, the objections boil down to the fact that the policy undermines basic principles of educational equity and excellence, two of the pillars upon which sound policy rests.

Violating principles of equity. Many educational leaders today emphasize the need for “equity” in K–12 education policies. For good reason. Equity, properly defined, works to ensure that all students are equally challenged to meet rigorous standards. Under Ohio’s conventional graduation requirements, students must pass certain state EOC exams (or meet career-technical or military-enlistment criteria). This adheres to equity principles that, when applied to graduation, expect all students—no matter their background or the school they attend—to meet standard requirements that indicate baseline readiness to succeed after high school.

This important equity principle is undermined when policymakers allow course grades to substitute for exams. There is no assurance that students receiving a “C” in one school versus another are equally competent in a subject. Remember, statewide grading standards do not exist. Every teacher has his or her own criteria. One may have extremely stringent grading practices, while another’s are less challenging. Some educators might include classroom participation and attendance in course grades, and others might lean more heavily on quizzes and exams.

Teachers’ grading practices shouldn’t be micromanaged by the state, but relying on course grades results in double standards. Unfortunately, disadvantaged students are more prone to fall victim to lower expectations, one of the regrettable consequences of policymakers failing to uphold basic principles of educational equity.

Violating principles of excellence. Education policies should motivate educators and students to strive for excellence in all that they do. As a way of encouraging high school pupils to reach their academic potential, Ohio has long required young people to pass state exams before they graduate. The prior iteration of state high school tests, known as the OGTs, assessed roughly eighth-grade-level content. But rightly understanding that the OGTs were a modest bar, Ohio developed a set of more demanding EOC exams that now ask students to demonstrate a greater depth of knowledge and skill in core academic subjects.

In contrast, course grades don’t offer the same incentives for students to master rigorous academic content. For instance, a Fordham study found that more than half of North Carolina students who failed to demonstrate proficiency on state algebra I exams received a course grade of “C” or above—wrongly affirming their mastery of the subject. Unfortunately, there has been no comparable analysis in Ohio, as course grades aren’t even reported to the state. But it’s plausible that thousands of students receive satisfactory course grades but struggle to achieve competency on state exams. Rather than lowering the bar and pushing through students who haven’t demonstrated firm literacy and numeracy skills, policymakers would better serve these young people by slowing the promotional train and asking them to solidify their abilities in content areas that are essential to lifelong success.

* * *

Some may argue that Ohio’s high school students deserve a free pass because of the disruptions of the past year. We must, of course, recognize these challenges and work to overcome them in the months ahead. But the year’s events don’t give policymakers free reign to discard policies that advance educational equity and excellence. To the contrary, it’s now more important than ever to hold fast to principles that put young people’s long-term best interests at the heart of policymaking.

NOTE: The Thomas B. Fordham Institute occasionally publishes guest commentaries on its blogs. The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of Fordham.

As Ohio policymakers continue to debate House Bill 1, legislation to reform the way the state funds schools, it is important that they continue to work to ensure the bill achieves its stated intent: to create a fairer and more equitable funding model for all of Ohio’s students. There is no doubt this is a gigantic undertaking. Unfortunately, as currently written, this legislation falls short of the mark in terms of funding Ohio’s seven public independent STEM schools.

The value and importance of STEM education cannot be understated. Members of the 127th General Assembly had the foresight to include a provision in the biennium budget that authorized the creation of public independent STEM schools, tasking them with developing and using innovative and transformative instructional methods with an emphasis on Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM). The schools were created, in part, to be research and development labs for education in Ohio, and to be incubators of STEM talent across the state to meet Ohio’s evolving workforce demand. Independent STEM schools have risen to the challenge.

Since that time, technology has become even more engrained in our everyday lives. Ohio’s public independent STEM schools actively engage students in the learning process and teach students how to learn. Each classroom is essentially a learning lab.

As the name implies, independent STEM schools operate outside of school districts. This allows the schools to not only be more agile with the programs they offer, but also permits them to accept students from a larger geographical region. While each school is unique, they all collaborate with local businesses, governments, and academic institutes to ensure the curriculum is meeting the needs of today’s workforce. Lessons at these schools focus on skill mastery and problem-based learning, again to actively engage students in their education. Additionally, independent STEM schools expose students to the career possibilities and prepare students for the industries of the future.

The successes of these schools are evident in many ways. Ohio’s independent STEM schools post a cumulative 100 percent graduation rate and have high rates of students who pursue STEM fields post-graduation. Demand far exceeds our capacity. Educators, businesses, and elected officials across Ohio and the country are interested in learning how to replicate our programs. Students, parents, and alumni testify to the difference their schools have made. Moreover, Ohio’s independent STEM schools take an innovative approach to education, and their successes don’t just benefit the students and families that attend them. We’re always happy to share best practices and provide training to educators across the state and nation. The ultimate goal is to see all students succeed.

While providing quality and innovative STEM education is still important to preparing students for the emerging workforce, independent STEM schools need equitable and sustainable funding to build on these successes. Unfortunately, House Bill 1, as written, does not accomplish that for Ohio’s independent STEM schools. Since the inception of independent STEM schools, they have had the lowest per-pupil foundation funding of any educational model, including traditional public, career-technical, and charter schools. In fiscal year 2019, the average per-pupil expenditure of $12,473 in traditional public schools was dramatically higher than the average expenditure of only $7,927 per student for independent STEM schools. Contrary to the goal of creating equitable funding for all students, House Bill 1 establishes a framework for school funding that would continue to promote inadequate funding for independent STEM schools. In fact, HB 1 proposes to fund public charter schools and independent STEM schools at 90 percent of their traditional school counterparts. This does not create equity, but continues to underfund innovative, high-quality, high-demand public school choice. Under the proposed funding model, independent STEM schools are projected to see a slight increase. But by building a reduced funding percentage into the framework, independent public STEM schools will never be fully funded, and will likely see the gap continue to widen.

Furthermore, independent STEM schools, by designation, emphasize personalized learning and real-life experiences and exposure to the workforce and emerging careers. Schools provide pathways in a variety of innovative fields like engineering, health, agriculture, and more. Each classroom is essentially a lab, and our teachers have deep knowledge and experience in these areas. The unique mission and fundamental requirements of independent STEM schools should be funded differently. The proposed funding increase in this bill falls short of the additional funding independent STEM schools need to support their robust career-exploratory programs designed to inspire and prepare future STEM professionals.

Over the years, Ohio’s independent STEM schools have used every process at their disposal to tap existing funds and reduce costs. They have leveraged community partnerships and built the curricula and programs to qualify for weighted funding through career-technical education. This has all been done while protecting and preserving the educational model. Regardless of how fiscally conservative they are, independent STEM schools are facing fiscal cliffs, and both current funding and that proposed in House Bill 1 are inadequate to allow them to continue to fulfill their mission as education incubators.

As the General Assembly continues to debate HB 1, members should ensure an equitable and sustainable funding model for independent STEM schools. This will allow these schools to continue fulfilling the mission they were tasked with in 2007. Innovation will be key to rebuilding Ohio’s economy after Covid-19. Independent STEM schools will be an integral part of that solution.

Meka N. Pace is the president of the Ohio Alliance of Independent STEM Schools.

As it has for much of the past two years, the Ohio House is currently discussing the latest version of the Cupp-Patterson funding plan, a significant rework of the state funding formula. The legislation (House Bill 1) may again sail through the lower chamber this spring, but whether it passes the Senate and garners the signature of the governor is another matter. While the plan has its strengths, a number of questions remain, most notably around its estimated $2 billion per year price tag.

The plan’s overall cost should be a first-order concern, but its policy details also merit attention. Lawmakers shouldn’t enact a system that future legislators will deem unsustainable and need to fix down the road.

With that in mind, the following piece examines one important aspect of the Cupp-Patterson model that hasn’t received much scrutiny thus far—its approach to setting a “base amount.” Note that this essay doesn’t address other concerns, already discussed on this blog, such as the absence of reforms that encourage wise spending or the inequitable treatment of charters. A forthcoming piece will tackle two additional issues: guarantees and interdistrict open enrollment.

Determining a base amount

One of the foundational elements of most funding formulas is a base amount, which is usually seen as representing the minimum cost of educating a typical student without any disadvantages or special needs. A distinctive feature of the Cupp-Patterson model is its extensive calculations that attempt to capture the cost of educating students, which is then used to determine districts’ base funding.

Before going any further, it must be noted that there is no settled way of determining the cost of educating a typical student. Analysts and consultants have developed a range of approaches that rely on different assumptions and methods, and that sometimes produce wildly varying results. For instance, during the early 2000s, two teams of analysts worked to gauge the costs of educating students in Texas and came up with estimates that were billions of dollars apart and equivalent to more than 10 percent of the state’s total education spending.

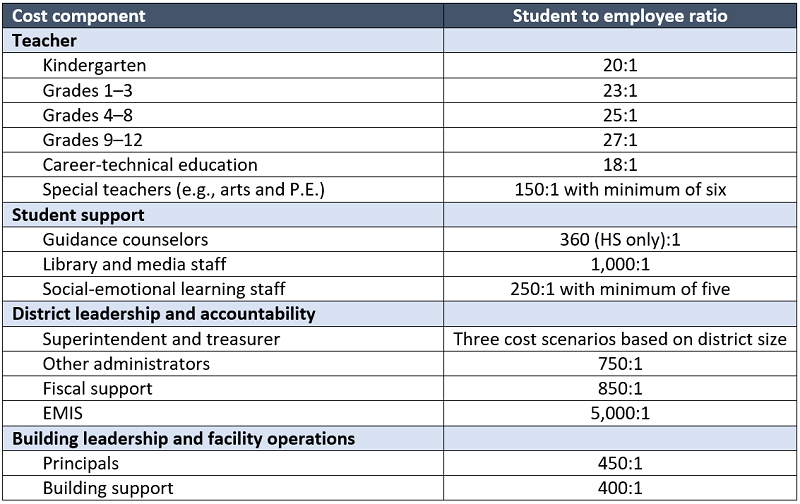

Despite the unsettled “science,” the Cupp-Patterson developers took a stab at estimating the costs and chose to implement an inputs-driven model that focuses on staffing ratios and salary data. The table below displays the major components of the formula. For instance, the framework provides one teacher per twenty-five students in grades four through eight. Thus, if a district has 100 students in those grades, its costs for that component would be four teachers times the average statewide teacher salary plus benefits. These computations, which would be written into statute, directly determine districts’ base amounts.

Table 1: Base cost calculations under the Cupp-Patterson funding plan

Note: Some elements that don’t rely on staffing ratios are omitted (e.g., supplies, building maintenance, and professional development). Districts are not required to actually implement these ratios as they are used only to calculate costs.

Because districts have different enrollment patterns, the Cupp-Patterson plan yields variable base amounts. According to LSC, these range from $7,000 to a whopping $15,000 per pupil, depending on the district. The base amounts of most districts (86 percent) fall between $7,000 and $8,000 per pupil, with a statewide average of $7,199 per pupil. This is a major shift from Ohio’s current approach to base funding, one that is also used by a majority of states. Rather than including cost calculations, the present formula sets a fixed amount that applies to all districts (currently $6,020 per pupil).[1]

It’s also important to note that, although the base amount applies to the core component of the state funding formula, it does not reflect the entirety of district revenue. Ohio districts receive billions more from state “categorical” funding (e.g., extra dollars for special education and economically disadvantaged students), supplemental local property taxes, and federal aid.

Concerns with the Cupp-Patterson approach

There are tradeoffs to these different approaches. The current formula’s fixed amount could be viewed as positive feature. It’s a straightforward and transparent way of setting the base, as it allows anyone to examine state law and find every district’s base printed in black and white. A fixed amount could also give legislators more budget flexibility. A simple change in dollar amounts can address a fiscal crisis, adjust funding for inflation, or boost expenditures above and beyond inflation. In fact, if legislators are intent on increasing education spending, they could simply ratchet up the current base amount to, say, $6,800 per pupil. On the other hand, the biggest criticism of a fixed base is that it’s often seen as an arbitrary figure, one that isn’t necessarily tied to the cost of educating students.

Now to the Cupp-Patterson plan. The advantage of this model is that it more explicitly links base amounts to costs, something that its advocates have routinely pointed out. They have also contended that putting the entire cost model into state law is more transparent, as one can see the “cost drivers” of education. Yet there many potential problems with the method, as well.

While many have praised the base-cost model of the Cupp-Patterson plan, legislators should step back and rethink whether putting the entire cost model into state law is a wise idea. If they feel a need to link the base with costs, they could disclose the calculations in a report. But putting the whole framework into statute might leave future legislators dealing with runaway spending—or facing cries (or litigation) arguing that they are failing to fund the state’s school funding model.

[1] In both the Cupp-Patterson model and Ohio’s current formula, a district’s base amount is adjusted to account for its local tax capacity (including a state-required minimum 2 percent property tax).

[2] House Bill 1 creates a nineteen-member School Funding Oversight Commission that would make recommendations about future modifications to the funding formula, including adjustments for inflation.

Concerns over the increased potential for cheating are front and center in debates over testing while students are learning remotely. A new report from a group of researchers at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI) in New York details their cheat-resistant online exam protocol, an innovation that could fill an immediate need and pave the way for the future of testing.

Methods of online proctoring exist, but they are often expensive, riddled with privacy concerns, and draconian, forcing students to, for example, keep microphones on and remaining in frame for an hour. They also signal to students, perhaps unintentionally, that adults don’t trust their honesty. Text-recognition software can discreetly detect plagiarism, but it’s useless on multiple-choice or calculation questions and younger students’ written work. Using a huge bank of test items to randomly deliver different questions to different students could also limit remote cheating opportunities, but it requires an extraordinary amount of work for educators and goes against best educational practices.

The RPI team sought to address the drawbacks of each of these models by creating a simple, cost-effective, and privacy-conserving solution that would help educators administer a valid remote assessment with minimal efforts. The key component of their model, called a distanced online test (DOT), is timing. Rather than having all students start the DOT at the same time, the test is broken down into sections which are given to different groups of students at various times. Those at the lowest-mastery levels of the content—as determined by midterm scores, current GPAs, SAT scores, or other class grades received prior to the DOT—start the test first. Once that lowest-mastery group has completed the first section, they move on to the next—with no option to return to previous sections—while the next-highest-mastery group starts the first section. And so on.

Without live proctoring, the main cheating concerns are internet searches for answers and collusion with others. Previous research into online testing found that nearly 80 percent of cheating events occurred via collusion, 42 percent via copying from the internet, and 21 percent falling into both categories. Statistical evidence suggested that collusion would be strongly suppressed by the DOT model’s staggered start. With no ability to return to closed sections, students wishing to collude would have to do so in real time. But the higher-mastery students—from whom help would most likely be solicited—would not be working on the same set of questions. Internet copying, meanwhile, could be addressed through question construction and a slightly larger question pool.

The main benefit promised by the DOT method was simplicity. No additional equipment required, no random question generators needed, and no violations of student privacy. While more test questions were required in the optimal DOT method—so that the test sections received by each cohort would not be exactly the same in content—the RPI team determined that a maximum pool just 1.5 times larger than the number of total test items would do the trick, especially if questions were mainly of a type that “require intellectual efforts [rather] than factual recalls.”

The RPI team honed their model and then tested it as a fully-remote, non-proctored final exam in a class where the midterm exam had been given fully in person earlier in the semester. Seventy-eight students took both exams, which each consisted of forty graded items. All were multiple choice questions. The DOT final was broken into two sections of twenty questions each. There were two mastery cohorts for the DOT final, and thus two starting times. The results of the midterm served as a control to which the DOT exam results were compared. Both exams produced the typical bell-shaped curve of a normal distribution of scores, and analysis showed that both distributions had the same mean value, demonstrating consistent evaluative results of the same population via the two very different types of testing methods. Their analysis also found random patterns of incorrect answer matches between any given pair of students—a traditional means of testing for evidence of cheating—and an approximately equal distribution of correct answers between the two test sections. This latter test was DOT-specific and attempted to account for the fact that more collusion was to be expected in one half of the exam versus the other. Given these findings, the RPI team determined that the DOT reduced the possible point gain due to collusion to less than 0.09 percent. Post-exam surveys indicated general approval of the DOT structure by students, reasonable assessment of question difficulty, and positive disposition toward ease of use.

The RPI team concluded that their DOT model not only met the criteria of an easy, cost-effective, non-proctored remote testing platform, but also that, when students knew they could not collaborate with others, they were more motivated to actually study the material to achieve correct answers themselves. These are all important aspects of good online exams, but it cannot be overlooked that the tested version of DOT was developed for college students, where the possibility of expulsion for cheating is a real concern, and that it included only multiple-choice questions and covered just two mastery cohorts. Whether this approach to online testing will work at scale in K–12 education is hard to know. But RPI’s simple strategy to stagger testing times might just be a way to lessen the potential for cheating.

SOURCE: Mengzhou Li, et. al., “Optimized collusion prevention for online exams during social distancing,” npj Science of Learning (March 2021).

Keeping high schoolers on track and motivated to complete academic work is a perennial worry, one of many such concerns that took on a new dimension over the last year. Now, a study in the Journal of Educational Psychology indicates that there are six distinct motivational profiles into which students can fit and that a student’s motivational characteristics can change over time. What’s more, the general trend for kids is toward more intrinsic motivational patterns from year to year, and it seems that specific, controllable factors can influence this movement.

Researchers surveyed 1,670 high school students from central and northeastern Ohio over two consecutive years. In the first year, 685 students were in ninth grade, 588 were in tenth grade, and 397 were in eleventh grade. The sample was split 50.5 percent female and 49.5 percent male. Reflecting the racial and ethnic makeup of the two regions, 82.0 percent of students were White, 5.5 percent were African American, 6.2 percent were Hispanic, 3.4 percent were Middle Eastern, and 2.9 percent were Asian American. While socioeconomic status and test scores weren’t reported for individuals, the schools that students attended ranged from 12.9 to 72.5 percent economically disadvantaged, and performance indices ranging from 51.9 to 85.8 percent (out of 100) on their most recent state report cards.

Students’ academic motivation was assessed via eight survey items adopted from a scale developed in the 1990s. This scale assesses students’ motivation toward school activities from fully intrinsic (learning for the simple enjoyment of the task) to fully extrinsic (doing the task only because one is forced by others), with various stages in between. Students were surveyed on their academic motivations in spring 2016 and again in spring 2017. Only students who fully completed both surveys were included in the study, although the researchers did run some comparisons between two-year and one-year survey completers to determine that there were no significant differences between the groups. Because previous studies on this topic had indicated a connection, the researchers also looked at students’ sense of school belongingness and their prior achievement levels as factors potentially contributing to academic motivation. School belongingness was assessed during the 2016 data collection only, using a five-item survey adapted from the psychological sense of school membership scale. Achievement was measured using weighted student GPA.

All students fit into one of six motivational profiles: (1) “amotivated,” meaning they had extremely low levels of all types of motivation; (2) “externally regulated,” meaning moderate levels of external regulation and low levels of all other types of motivation; (3) “balanced demotivated,” low levels of all types of motivation in a balanced pattern; (4) “moderately motivated,” moderate levels of all types of motivation; (5) “balanced motivated,” high levels of all types of motivation in a balanced pattern; or (6) “autonomously motivated,” low levels of external regulation and moderately high levels of other more autonomous motivation types.

Students fitting the balanced motivated profile predominated in both years of the survey—36.59 percent of students in year one and 36.17 percent in year two—with students fitting the moderately motivated profile accounting for nearly 30 percent of students in each year, the second-largest profile. While the membership of those two profiles stayed the most stable, latent transition analysis showed that, depending on which profile they started in, between 40 and 77 percent of students changed profiles between years. And those changes were largely for the better, assuming that having more intrinsic motivation is “better.” For example, 8 percent of students fit the autonomously motivated profile in the first year, a share which increased to 11.4 of students in the second year. Meanwhile, membership in the amotivated profile shrunk from 2.8 percent of the total to 2.1 percent.

The researchers speculated that developmental maturity could be one reason for the changes in motivation. Moreover, results of the school belongingness survey consistently predicted students’ shift into more-autonomous profiles over time. When students had a higher sense of belongingness at school, they were statistically more likely to shift into a more-intrinsic motivational profile than to stay in the same profile. Students with higher belongingness scores were also more likely to stay in the same profile than to shift downward. Year one GPA likewise was a significant predictor of year two profile membership in a similar manner. The higher a student’s year one GPA, the more likely they were to stay put or shift upward. This was especially true for those starting in the “lower” profiles in year one.

The report concludes with the recommendation that schools should routinely assess students’ motivation to identify those who are most at risk for dropping out or underperforming. However, that would likely only benefit students falling into the two “lowest” profiles. It seems that making sure all students are fully connected to their schools and are achieving academically at their highest possible levels is a much stronger path toward increasing student motivation across the board.

SOURCE: Kui Xie, Vanessa W. Vongkulluksn, Sheng-Lun Cheng, and Zilu Jiang, “Examining high-school students’ motivation change through a person-centered approach,” Journal of Educational Psychology (February 2021).

NOTE: On Monday, March 1, 2021, members of the House Finance Subcommittee on Primary and Secondary Education heard testimony on House Bill 1, which would create a new school funding system for Ohio. Chad L. Aldis, Fordham’s Vice President for Ohio Policy, gave interested party testimony before the subcommittee. These are his written remarks.

Thank you, Chair Richardson, Ranking Member Troy, and House Finance Subcommittee on Primary and Secondary Education members, for giving me the opportunity to provide interested party testimony today on House Bill 1.

My name is Chad Aldis, and I am the Vice President for Ohio Policy at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a charter school sponsor.

The Fordham Institute has long advocated for reforms that put Ohio students and parents at the center of school funding policy. We strongly support principles such as “funds following students” to the schools in which they actually attend, and “weighted student funding,” in which extra resources are devoted, for example, to low-income, special-education, and English language learning students.

The plan before you in HB 1 proposes some important improvements that would better align Ohio’s funding system with these core principles. We strongly support the following aspects of the plan:

Of course, there is always room for improvement, especially with something as complicated as a school funding plan. Here are a couple of concerns that we have:

As for charter schools, we’ve written extensively on the large shortfalls, relative to their local district, that they face in terms of overall taxpayer funding. Despite educating children of similar backgrounds, brick-and-mortar charters in the Ohio Eight receive on average about $4,000 per-pupil less than their local district. The discrepancy is due to the fact that local funding, with limited exceptions, does not follow students to charter schools.

As a matter of fairness to charter students—most of whom come from low-income families or are students of color—the state should work towards funding equity for charters. While HB 1 improves upon the initial version of the plan that was in HB 305, the treatment of public charter schools remains concerning. On a positive note, recent estimates indicate that Ohio Eight charters would see an average funding increase of $1,389 per pupil under this plan. This is a step in the right direction. Unfortunately, the plan does not narrow funding gaps between Ohio’s urban charters and urban districts. Because the average funding for Ohio Eight districts increases $1,713 per pupil, the funding gap actually grows.

This inequity puts charters at a tremendous disadvantage relative to their nearby districts in competing for talented teachers and offering comparable academic and non-academic supports. Also worth noting is the relatively small increases that general-education charter high schools would see under the proposal, often below $1,000 per pupil. One of the state’s finest urban high schools—Dayton Early College Academy (DECA)—actually loses $82 per student under the plan.

Leveling the playing field between charters and districts is a heavy lift, but the following tweaks to the funding plan would improve equity for charters:

Finally, we recommend several changes to HB 1 to ensure that charters are treated fairly over the long term. They are as follows:

As a final note, you’ve probably noticed that my testimony doesn’t describe the current school funding system as unconstitutional. There’s a good reason for that. In a paper that we published in December, we think the scope of the legislative changes since DeRolph have given Ohio a fundamentally different school funding system than the Court examined in that landmark case. Assumptions that the current system is unconstitutional are just that—assumptions. That being said, we share the bill authors’ belief that the current funding system can and should be improved.

In conclusion, we believe that House Bill 1 has important strengths that would significantly improve the state’s funding system. Yet uncertainties remain around financing the plan’s costs and its approach to funding public charter schools. Thank you for the opportunity to provide testimony.