Comparing Ohio K–12 education to other states helps us gauge the pace of progress, provides ideas on improvement, and gets us out of our local “bubble.” In a recent post, my colleague Chad Aldis examined Ohio and Florida’s NAEP results, finding the Buckeye State wanting in terms of gains over the past decade. Terry Ryan has also offered an insightful comparison of Ohio’s charter policies to Idaho’s. This piece follows a similar path and takes a look at Ohio’s charter landscape relative to Arizona’s.

Why the Grand Canyon State? For starters, Arizona has a significant charter enrollment of about 180,000 students, or 16 percent of public-school enrollment (Ohio has roughly 110,000, or 7 percent). Arizona charters are also producing some stellar results. As Matthew Ladner has repeatedly (and I mean repeatedly) shown, Arizona charters have posted high scores on NAEP—and for two years straight, US News & World Report placed several of them in its top-ten high schools in nation.

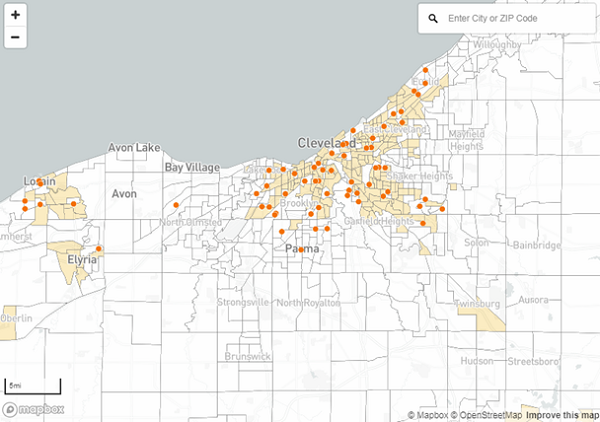

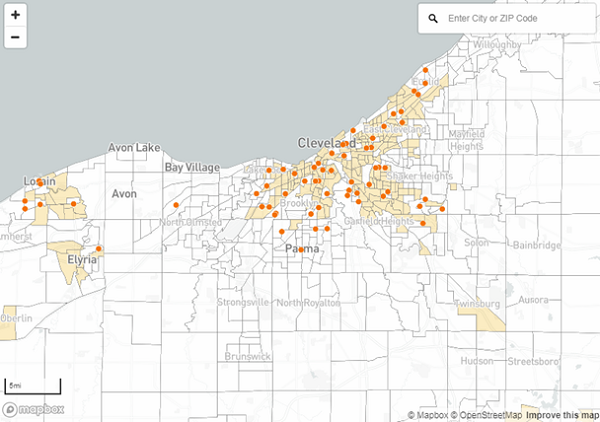

Let’s start by comparing a couple terrific maps that my Fordham colleagues produced in their recent Charter School Deserts report. Figure 1 displays the charter locations for the Cleveland metro area. What you’ll notice is that the vast majority of charters—the orange dots—are located within the city limits and largely in high-poverty neighborhoods (areas shaded in pink). Yet charters are noticeably absent from outlying high-poverty communities, such as Willoughby, Mayfield Heights, Solon, Strongsville, and Avon Lake.

Figure 1: Locations of charter schools in the Cleveland area

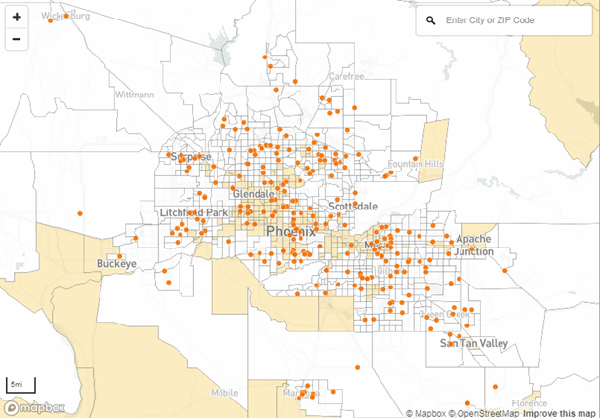

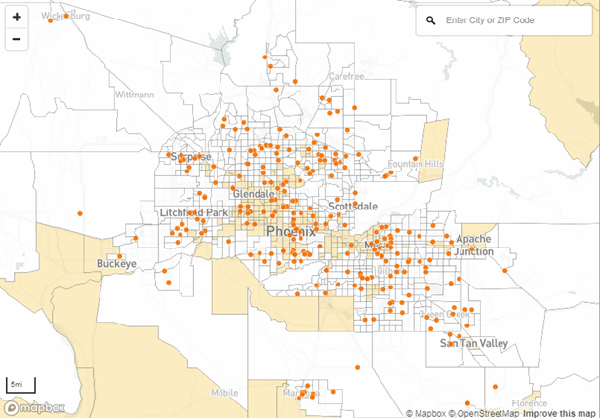

Now let’s look at Phoenix. This figure shows a remarkably wide geographic distribution of charters—literally all over the map. They’re located in high-poverty, inner-city neighborhoods, as well as more affluent suburbs, like Litchfield Park, Surprise, Scottsdale, Gilbert, and Queen Creek. You could live almost anywhere in metro Phoenix and not be more than fifteen minutes from a charter school. That’s not the case if you happen to live in a Cleveland suburb.

Figure 2: Locations of charter schools in the Phoenix area

These maps reflect very different policy approaches to charter-school formation. On the one hand, Arizona (and almost every other state) places no geographic limits on charter development, while Ohio places strict restrictions. Under Ohio law, startup charters are only allowed to open in “challenged” school districts, including those in Lucas County, the Big Eight, and other “low performing” districts, as defined in statute.[1] Today, startup charters are limited to just thirty-nine out of Ohio’s 610 districts. This explains the absence of charters in suburban Cleveland and almost anywhere else outside of Ohio’s urban core (see the full state map here).

Putting a geographic lid on charter formation does have some upsides. It has focused school developers’ attention on Ohio’s highest-poverty areas—locales where the educational needs are the greatest. Today, the Buckeye State is blessed with some terrific urban charters that are significantly improving students’ lives. It also avoids the political rancor that would likely follow a removal of suburban districts’ “territorial exclusive franchise” over public education, as Ted Kolderie once put it.

But with stronger charter accountability laws now in place, Ohio lawmakers should work to remove these geographic restrictions. Here’s why.

Suburban families are searching for different public school options. Although polls indicate that a majority of parents give their local public schools solid marks, about 40 percent are less satisfied, and a similar proportion think that more options would be beneficial. If Arizona is a bellwether for actual demand, a fair number of suburban parents are indeed seeking different schools for their children. For example, the Great Hearts charter network offers a distinctive classical liberal arts curriculum; today it has twenty-three schools across metro Phoenix and waitlists of some 20,000 students. Also in the Phoenix area are BASIS charters, which recently dominated the US News’s top-ten rankings. They’re proving to be a solid option for middle-class families seeking rigorous academics. It’s not just Arizona either. Recently, Wired magazine wrote on Design Tech High School in Silicon Valley, a charter school that, in close partnership with Oracle, focuses on technology, design, and entrepreneurship. Even in Ohio, some suburban families are trekking to quality charters like Columbus Preparatory Academy and Arts and College Preparatory Academy located just within big-city district limits. And as Charter Deserts so starkly reveals, many suburban families in Ohio are low-income households whose children are most in need of quality school options.

Charters in booming suburbs would provide options for families seeking smaller learning environments, especially in high school. I graduated from a mid-sized high school with a class of about 300 students. At times, I felt lost in a school of that size. But there are larger high schools than even that: In last fall’s enrollment counts, forty-two Ohio high schools reported senior classes of at least 400 students—many located in suburbs like Mason, Lakota, Kettering, and Olentangy. As these communities continue to grow and fill sprawling comprehensive high schools, some students may find it difficult to develop close relationships with teachers or classmates. Indeed, that may already be happening, as recent survey data found that public-school teenagers report weaker connections with adults working in their schools. Though many families and students will prefer large-school environments for a variety of reasons, others might want the smaller settings that charters often offer.

Charters in rural and small towns can foster close-knit communities of support. Thus far, we’ve concentrated on suburban locales, but the charter model can also provide opportunities for families in rural and small towns. Consider Ellen Belcher’s eye-opening profile of Sciotoville Elementary Academy that illustrates how one charter school in rural Appalachia goes the extra mile to serve its families and students. Other rural residents around the nation (including—you guessed it—Arizona) have used the charter model to maintain a cohesive community. Due to modest populations, small town and rural charters may never gain economies of scale, necessitating more creative ways to organize learning. But all communities, even smaller ones, should have the ability to form public schools that meet their local needs.

Allowing new charter school formation throughout Ohio would broaden support. National polling suggests that most people know little to nothing about charter schools. With almost no presence across massive tracts of Ohio, odds are that most Buckeye families know little about charters (alas, save perhaps for ECOT). This means Ohio charters have a narrow base of support, limited to those who have been well served by them and people who generally agree with the concept of school choice. To build a broader, stronger base of support, the next generation of Ohio charters will likely need to serve families and students from a wider range of communities.

* * *

The lesson from the Arizona is that families of all backgrounds and walks of life can benefit from charter schooling done well. Of course, simply removing Ohio’s geographic cap is no guarantee that charters will actually open in untouched parts of the state; it’ll take a supply-side response from educational and community leaders willing to start schools, as well as parents who enroll their children in them. But removing this legal barrier to entry is a necessary first step for charters to grow throughout all areas of Ohio.

[1] Districts themselves or regional Educational Service Centers may open a “conversion” charter school in non-challenged districts. In 2017–18, just 14 percent of Ohio charters are conversions.