Will more Ohio parents continue homeschooling after the COVID-19 crisis?

With widespread school closings, the phrase “we’re all homeschoolers now” has entered our nation’s vocabulary.

With widespread school closings, the phrase “we’re all homeschoolers now” has entered our nation’s vocabulary.

With widespread school closings, the phrase “we’re all homeschoolers now” has entered our nation’s vocabulary. While many schools are doing their best to continue instruction through online or send-home material, the shutdowns also mean that millions of parents now have new responsibilities for their kids’ learning. (To help in this task, we at Fordham have compiled some of our favorite educational tips and resources, as have others.) With no clear end in sight to the health crisis—and closures during the 2020–21 school year possible as well—parents will likely continue to perform some type of “homeschooling” over the coming weeks and months.

A few commentators have suggested that this experiment in mass homeschooling will inspire more parents to continue this form of education once the crisis passes. Whether that materializes is yet to be seen, but the temporary need to stay home may be putting homeschooling on more parents’ radars. With that in mind, some families may be wondering how to continue at-home instruction, and this piece provides a short primer on Ohio’s homeschooling policies and trends. Note that this piece focuses on “traditional” homeschooling, not online learning via publicly funded virtual charter schools—another form of at-home education. E-school policies are much different and a discussion of them is a topic for another day (see here and here however for more).

Policy

Each state sets its own rules around homeschooling. Some states have tighter requirements, with Ohio being one of the more stringent states in two significant ways. First, Ohio parents must notify their local district that they’re homeschooling, something that several other states don’t require (e.g., Illinois and Michigan). In fact, the Buckeye State has fairly detailed notification rules. Prospective homeschooling parents must submit the following to their home district (among a few other minor items):

The superintendent of a family’s home district reviews these notifications, and he or she may deny a parent’s request to homeschool based on non-compliance with the requirements above. While it’s not clear how often parents’ requests are denied (if ever), state rules detail an appeals process that includes an opportunity to provide more information to the superintendent, and eventually to make an appeal before a county juvenile judge.

The other major requirement that Ohio includes—which a number of other states do not—is testing. To continue homeschooling, parents must submit a yearly assessment report which may be based on: (1) a nationally normed referenced test; (2) a “written narrative” describing a child’s academic progress; or (3) an assessment that is mutually agreed upon by a parent and superintendent. But that’s not all. Should a homeschooling student fail to demonstrate “reasonable academic proficiency,”[1] the superintendent must intervene by requiring parents to submit quarterly reports about instruction and academic progress. If a child continues to fall short, the superintendent may revoke a parent’s right to homeschool their child, though that decision may be appealed to a county juvenile judge.

A few other homeschooling policies of note:

From a compliance standpoint, homeschooling isn’t as easy as simply deciding to stop sending a child to school. Rather, Ohio parents face several procedural steps before they can homeschool. For better or worse, it’s not an entirely permissionless activity. But as the next section indicates, an increasing number of parents are wading through the red tape to homeschool their kids.

Participation

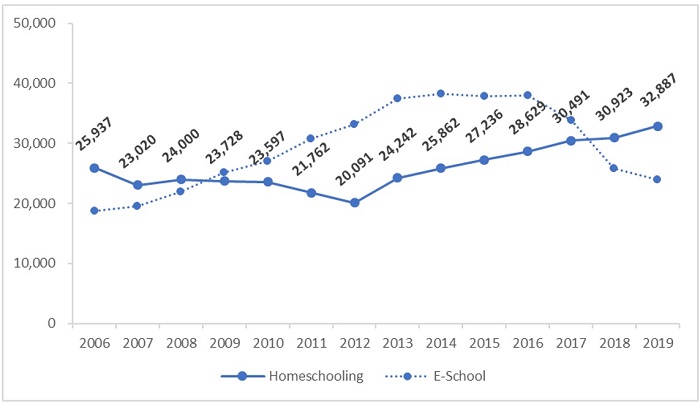

As the chart below indicates, roughly 32,000 students are homeschooled. While that represents a small fraction of all Ohio students (about 1.5 percent), homeschooling numbers have risen since 2012 even as Ohio’s overall school enrollment has declined. A number of factors could explain the uptick. Perhaps the post-recession economic growth has enabled more families to have a stay-at-home parent who can educate their kids. Maybe there’s some increased dissatisfaction with traditional school options (there’s some anecdotal evidence that African American parents are turning to homeschooling as an escape). It’s also possible that the 2013 adoption of a “Tim Tebow law” that permits homeschooled student to participate in district athletics has contributed. The recent declines in online charter enrollment (due largely to the closure of ECOT) might suggest that some former e-school parents are switching to homeschooling. Last, a growing network of supports (co-ops or support groups) and educational resources, including curricula and online materials, may be encouraging more parents take the plunge.

Figure 1: Number of homeschooled students, 2005–06 through 2018–19

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: Online charter school enrollments, another form of at-home learning, are also displayed for context.

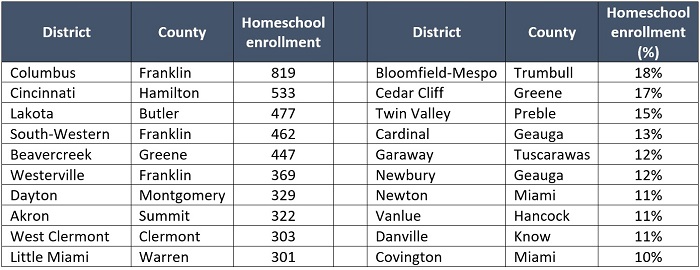

Perhaps in support of the “network” hypothesis are data indicating that homeschooling is more popular in some places than others. The table below displays the top-ten districts with the most homeschooling students, in terms of both absolute numbers (left panel) and as a percentage of district enrollment (right panel). Not surprisingly, we see a mix of larg districts on the left side (mostly urban and suburban). But it’s interesting to note some differences in participation when comparing districts of similar size and demographics. For instance, the suburban Columbus district of Westerville has more homeschoolers (369 students) than the almost equally sized suburban district of Dublin (140 students). Similarly, Cincinnati has far more homeschoolers (533) than Cleveland (140 students). Are those differences due to stronger parent networks? Meanwhile, the right panel shows a number of districts with relatively high shares of homeschooling enrollment. Bloomfield-Mespo, north of Youngstown, leads the state with an 18 percent share and Cedar Cliff (near Dayton) is just behind. Again, it seems plausible to think that the availability of local supports explains the higher percentages of homeschooling.

Table 1: Top homeschooling districts in absolute numbers and as share of district enrollment, 2018–19

Source: For a full listing of homeschool enrollment by school district, see the ODE file “Homeschool Student Data.” Aside from enrollments, no other data on homeschooling students is available via ODE.

***

No school option, whether traditional district, public charter, private, or homeschooling, is the right fit for every family or student. Out of necessity, millions of Ohio parents are experiencing first-hand what homeschooling would be like. For many—likely the vast majority—they’ll come to a deeper appreciation of the hard work their local schools do to serve children. But some might just find themselves attracted to a form of schooling they would’ve never otherwise considered. For these parents, taking a look at the policies and the homeschooling supports in their community would be a good place to start.

[1] This term is only clearly defined in state policy when a norm-referenced test is used (scoring at least 25th percentile).

On March 22, Governor DeWine issued a stay at home order for Ohioans. While essential businesses such as grocery stores, gas stations, and banks are still in operation—one hopes with social distancing and beefed up sanitation measures in place—the vast majority of life as we know it has ground to a halt until at least April 6.

For schools, the stay at home order didn’t change much. They were already physically closed through April 3, and although vital services such as meal distribution have been altered, they are still striving to educate students. Nevertheless, given Governor DeWine’s laudably cautious approach to public health and the fact that the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases continues to rise, it’s increasingly likely that Ohio schools will be closed for the remainder of the year.

So what does that mean for students, families, and schools? The General Assembly recently passed legislation that addressed state testing and report cards, school accountability, graduation requirements, and attendance. But closing buildings when there’s still two or three months remaining in the year means that schools will need to continue offering some type of distance learning and academic support until summer break officially hits (and possibly after).

To get a better idea of how Ohio schools are handling these unprecedented times, I took a look at the information that Ohio’s three largest districts—Columbus City Schools (CCS), the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD), and Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS)—have posted online regarding their response to the coronavirus shutdowns. Obviously, this does not offer an exhaustive list of all the efforts these districts are making, but it’s helpful to examine the information that’s readily and consistently available online for parents who may be searching for support.

In general, each district’s website includes information related to three big areas: academic resources, food distribution, and health and social services. Let’s take a look at each.

Academic resources

In Cincinnati, teachers have created lesson plans for students that they’re calling “enrichment packets.” These cover the core content areas—English, math, science, and social studies—and are organized by grade level. Families can download these packets from the district’s website, but CPS also shared them with Cincinnati-based Staples stores. Parents are able to walk into the nearest Staples and request that their child’s packet be printed for free through March 28.

Cleveland and Columbus have made similar efforts. CMSD’s website offers resources for grades K–12, and printed packets can be picked up at sites where the school is distributing food. CCS also offers printable resources online for all grade levels and multiple subject areas. What sets Columbus and Cleveland apart, though, is that they’ve also compiled links to other academically-oriented sites and resources that parents may find useful. CMSD, for example, provides a link and login information to Scholastic Learn, a link to an Accelerated Reader book finder, and information about free online AP review courses. CCS, meanwhile, has provided instructions for parents on how to use iReady at home, and printable resources for parents who have students that are classified as gifted, special needs, and ESL.

It’s difficult to determine whether these districts are offering full-fledged distance learning opportunities in addition to enrichment resources. The Ohio districts that have already transitioned to full-time online instruction are typically doing so at the building and classroom level. Such communication occurs directly and privately between individual schools, teachers, and families, and wouldn’t be posted on the district website. Others are waiting to see just how long the closures will last. If kids will be back in school soon, trying to get a massive online education effort temporarily off the ground might not be the best use of their time.

It’s also worth noting that there are thousands of students who lack internet access or internet-enabled devices. Going online full-time is more complicated in Columbus, Cleveland, and Cincinnati than it may be in some of their neighboring, more affluent suburbs. Such large districts will need more time to get things up and running. If schools do close for the rest of the year, it will be important to check back and see how these and other districts are making the transition to full-time distance learning.

Food distribution

One of the biggest concerns about closing schools was what would happen to the tens of thousands of students who rely on school breakfast and lunch programs for daily nutrition. Fortunately, all three of Ohio’s largest districts—and nearly every other district in the state—are still distributing food to kids who need it. CPS is handing out to-go meals at twenty-four sites located around the district. CCS is distributing grab-and-go breakfast and lunch at fifteen locations, and the Central Ohio Transit Authority is offering students and families free transportation to and from pickup sites. CMSD is also providing shuttle service to and from their twenty-two food pickup locations.

Health and social services

Folks who don’t interact with schools on a daily basis often don’t realize just how instrumental they are to distributing information and resources throughout their communities. In times of crisis, local schools are a vital touchpoint between government and families. That’s why it’s heartening to see that all three of Ohio’s largest school districts have taken pains to include on their websites a ton of useful information that isn’t directly related to academics. For example, all three districts have easily-located links to the CDC and other health organizations, such as the Ohio Department of Health. Each district also has links to resources that parents can use to discuss the coronavirus with their children. Several of these resources are available in languages other than English. Both CMSD and CCS offer information about local companies providing free Wi-Fi. And CCS has an entire page devoted to community resources such as the location of local foodbanks, mental health resources, family activities and resources from the Columbus Metropolitan Library, and information about housing, unemployment, and utility bill assistance.

***

These are uncharted waters. When things finally go back to normal—hopefully sooner rather than later—it will be important for analysts, researchers, advocates, and educators to collect as much information as possible about what schools did, how it worked, and lessons learned. But in the meantime, it’s important for schools to provide as much information and support as possible to students and their families. Based on the information they’ve communicated to families thus far, Ohio’s three largest districts are working hard to rise to the challenge.

The Knowledge is Power Program, or KIPP, is the nation’s largest charter school network. It currently operates 240 schools that serve more than 100,000 students, the vast majority of whom are low-income students of color. The network is widely known for its sizable impact on student achievement, as demonstrated by standardized test scores, but there are less data on longer-term outcomes like college enrollment, persistence, and completion.

To remedy this lack of post-secondary data, a recent report examines two key questions: the impact of KIPP middle schools on students enrolling in four-year colleges, and the impact on students persisting in those colleges for two consecutive years after high school graduation. The report follows a sample of 1,177 students who applied to a fifth or sixth grade admissions lottery for the 2008–09 or 2009–10 school year in the hope of enrolling at one of thirteen oversubscribed KIPP middle schools located throughout the country. Data from a total of nineteen admissions lotteries were used, with each lottery representing some combination of school, cohort, and entry grade levels.

The report uses a variety of sources: college enrollment data from the National Student Clearinghouse, administrative data from the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, and student rosters provided by the KIPP Foundation. Baseline data on the sample came from a prior KIPP middle schools study that included lottery application records and demographic and socioeconomic information.

The authors used a random assignment design to ensure that treatment and control groups were similar on both observable and unobservable characteristics. They conducted two analyses. First, they used a primary impact estimate to compare students who received an admission offer via the lottery to students who didn’t. They note that this is a more conservative approach, since it includes students in the treatment group even if they declined their enrollment invitation. In an exploratory analysis, however, the authors focused on students who actually attended a KIPP school in order to more directly measure KIPP’s potential effects.

Now for the findings. First, KIPP middle schools had a positive and statistically significant impact on enrollment in four-year colleges. On average, students who received an admissions offer were 6.9 percentage points more likely to enroll in a four-year college than students who applied to a lottery but were not offered admission. When focusing on students who actually attended KIPP, the impact estimate nearly doubles to 12.9 percentage points. They note that an effect of this size represents a “meaningful change” in college enrollment rates given the national gap between white and black or Hispanic students. To wit, “The impact of attending a KIPP school (10 to 13 percentage points) would be almost large enough to erase the nationwide racial disparity in college enrollment rates,” write the authors.

The effects on college persistence are also encouraging, though not quite as clear as the enrollment findings. The primary impact estimates indicate that students who received KIPP admissions offers were 4.8 percentage points more likely to enroll in a four-year college after high school graduation and remain enrolled for two years, although that difference was not statistically significant. Digging deeper, the exploratory analysis found that roughly 33 percent of students who attended KIPP enrolled in a four-year college and persisted for two years, compared to around 24 percent of student who did not attend KIPP. However, this difference of 9 percentage points was not statistically significant.

Overall, the magnitude of KIPP’s impact on four-year college enrollment was larger than for college persistence. The authors explain that this difference could be due to multiple factors. For instance, the initial enrollment effect could be fading over time if treatment group students drop out at higher rates, enroll in college later, or transfer from two-year to four-year colleges at higher rates.

The students in this study have only had enough time to complete two years of college, so it’s still too early to know whether KIPP will lead to improvements in college graduation rates. But the authors note that the estimated impacts on persistence are worth considering in relation to potential future college graduation rates. “If a future study revealed that KIPP middle schools ultimately do have an effect of approximately 9 percentage points on college completion, that effect would be equal to more than a third of the degree-completion gap for black and Hispanic students,” they write.

If this does indeed turn out to be the case, KIPP deserves considerable praise for helping more students get to and through college. It’s also worth noting that KIPP has changed its model considerably since the late 2000s when the students in this sample were in middle school. These changes were made in part because the network reviewed its own data and found that many graduates were getting to college but weren’t making it through college. As a result, it’s possible that KIPP’s long-term impacts will get even bigger over time once researchers begin to study samples of students that attended KIPP after the network’s changes.

Source: Thomas Coen, Ira Nichols-Barrer, and Philip Gleason, “Long-Term Impacts of KIPP Middle Schools on College Enrollment and Early College Persistence,” Mathematica (September 2019).

A plethora of research and a dollop of common sense tell us that the viability of school choice depends on families being able to access the choices available to them. One key to access is transportation. Yellow buses are so ubiquitous as to border on symbolic representation of education itself. But families opting out of their resident districts—for charter schools, private schools, or interdistrict choice—are often forced to forgo reliable yellow bus transportation. But not always. And it is this variability that a new report from EdChoice seeks to illuminate.

Authors Michael Q. McShane and Michael Shaw utilized a legal research platform and a detailed language search of the legal codes of all fifty states to discern how each one identifies, funds, and delineates responsibility for transporting charter, private, and open enrollment students. While they summarize the results as “tangled,” some commonalities and patterns emerged.

In general, transportation funding primarily comes from states as a per-pupil amount designated specifically for transportation, although many states allow districts to supplement those with local dollars if desired. All states impose regulations on districts pertaining to things like school bus safety, background checks of drivers, and emissions standards—although the level of detail varies greatly state to state. Some state departments of education offer route-planning resources to their districts, but most are just looking for data from their districts, up to and including maintenance and daily route mileage. In some urban and suburban areas, districts may also utilize existing public transportation options by either reimbursing families for fares or partnering with regional transportation agencies to provide eligible students with passes. What is most in evidence at the macro scale is that states provide the lion’s share of the funding while districts do the lion’s share of the work. The inevitable push and pull of this dynamic comes most strongly to the fore when considering those students who opt out of their resident district’s schools.

The research design used in-district transportation mandates as the baseline. This includes situations such as districts being allowed to deny transportation to resident students living within a small radius of their assigned buildings or to resident students at higher grade levels. The authors then looked to see whether students utilizing various forms of choice were given equal, close-to-equal, or unequal transportation access.

For those exercising interdistrict choice, or attending school outside of their geographically assigned school district, thirty states have an explicit provision for transportation. Six of these states mandate equal or close-to-equal transportation access compared to what is offered to students attending the district.

Although language against “compelled support” of religion and/or Blaine amendments appears in most state constitutions, twenty-nine states currently have provisions to supply transportation for private school students. There are caveats aplenty—such as transportation being available only for students with disabilities or students transferring out of low-performing schools—but seven states mandate transportation services and funding at equal or close-to-equal levels as those for resident students.

Charter schools, often the most contentious of school choice options, have transportation funding or services available in thirty-one states. Of those, seventeen mandate support for charter school student transportation at equal to or close-to-equal levels as those of resident district students.

Despite the majority of states offering transportation of some sort to school choice students, state level mandates can run up against the reality of funding, geography, and district whims. What districts determine as a feasible route could mean multiple buses, early starts, and long commutes for young students. No matter how much transportation equality states spell out, sometimes parents utilizing choice win; sometimes they lose.

McShane and Shaw provide four recommendations for improvements at the state level. First, states should appropriate funding for charter schools to transport their students to their schools, bypassing districts. Second, private school choice programs should allow pupil transportation as an allowable use of education savings account, tax-credit scholarship, or voucher dollars. Third, states should not artificially restrict pupil transportation methods such as public transit. And fourth, state policymakers should look to improve the quality of the current pupil transportation system.

The authors also provide one recommendation at the local level: Schools and districts should look to out-of-the-box solutions such as route optimizing software and shared services with other providers to improve their transportation systems and drive down costs. Perhaps if transportation were cheaper and more efficient, more students could more easily access it no matter where their destination.

SOURCE: Michael Q. McShane and Michael Shaw, “Transporting School Choice Students,” EdChoice (March 2020).

Update (3/30/20): On March 27, Governor Mike DeWine signed legislation waiving state assessment requirements for the 2019-20 school year.

Update (3/23/20): On March 22, Governor Mike DeWine stated his support for waiving state assessments for the 2019-20 school year. The state legislature is expected to pass a bill that would formally waive the exams for the year.

Governor Mike DeWine, along with other state leaders across the nation, have taken dramatic steps to slow the coronavirus pandemic, including shuttering schools. On March 12, the governor announced that all Ohio schools would close from March 17 through April 3 (though schools are encouraged to offer online instruction and/or provide take-home materials). So far, no decision has been made as to whether the closures will extend beyond April 3. Likely preparing for the worst, Governor DeWine recently acknowledged the possibility of closing schools for the rest of the school year.

Though surely a low priority in light of the health crisis, questions have arisen about what Ohio should do about state assessment and accountability for the year. In normal circumstances, exams are taken mostly in April, but the closures are likely to extend into that month if not beyond. Recognizing the extraordinary situation, the U.S. Department of Education has said it would approve one-year waivers in some circumstances to states seeking relief from testing requirements under federal law (a number of states have already made petitions).

How should Ohio navigate these uncharted waters? The answer likely depends on how long schools will remain physically closed. Let’s take a look at two of the most likely scenarios.

Scenario 1: Schools close for rest of the year

If schools are shut through June 2020 due to prolonged health concerns, there’d be no state testing, period. Without test data, it would be irresponsible for the state to release standard report cards for 2019-20, including overall and component grades.

Still, the state could publish, for information only, data against a few indicators. For high schools, the state could release graduation rates and other measures within the prepared for success component. Those data are all lagged—reflecting the classes of 2018 and 2019—and thus would not be affected by the closures. In elementary schools, Ohio could potentially calculate a modified version of the K-3 literacy component, which mostly looks at diagnostic testing results taken in the fall by Kindergarten to third grade students. (The calculations do, however, incorporate the spring third grade ELA test.) This leaves just middle schools without any current data should state exams be cancelled.[1] All districts, of course, have elementary and high schools, and would thus have graduation and prepared for success data, as well as most elements of the K-3 literacy component.

Due to the lack of complete data, the state should refrain from using the results to inform any type of high-stakes decision such as charter school closure, academic distress commissions, EdChoice designation, and the like. Those types of accountability mechanisms should be suspended for the year.

Scenario 2: Schools open sometime before the end of June

It feels like it might take a miracle, but there’s always the possibility that the crisis abates and schools reopen. In this best-case scenario, Ohio could administer state exams—and it would also have the necessary data to compute all the components of the report card. Whether it should do so is debatable.

On the question of to test or not to test, there are pros and cons. In favor of cancelling tests even if schools open, one could argue that the exams won’t provide useful information about student or school performance after such a prolonged hiatus. There’s some truth to that: It’s almost certain, for example, that student proficiency rates would be systematically lower than in prior years due to the lost learning time. One could also assert that subjecting students to testing feels a bit tone-deaf after going through weeks of coronavirus misery. Last, some may argue that schools should spend these precious few weeks catching students up through intensive instruction, and that assessment can wait until either the fall or the next spring.

On the other hand, administering exams would allow educators and parents to gauge where exactly a student stands after an extended break from school. Some students will have made progress while learning at home; others will have regressed. Without an assessment, no one will know what happened. Moreover, because of the break, a larger-than-usual number of students may require significant academic intervention—remember, the need to achieve proficiency in English and math hasn’t changed—and the sooner that teachers and parents know the extent of the need, the better they can prepare. If, with federal support, schools were encouraged to offer summer interventions, the results could also be used to determine which students get priority. Should the state go in this direction, it would need to ensure that test results are returned to schools in a timely fashion, so that educators have time to use them to inform summer or fall instruction.

Given the magnitude of the health crisis, Ohio may well close schools through June. However, in the event that schools can open safely, my view is that the state should consider statewide assessment. Getting a handle on the academic situation of students would put educators in a better position to hit the ground running this fall. As for the use of the state exam data for report cards in this scenario, Ohio could report the results for information only, but not use them to assign ratings. Nor should they be used to determine consequences in 2019–20.

* * *

My hope is that there would actually be state exams this year. This is not based on a heartless desire for testing in such trying times. Rather, it would mostly be a sign that things are, at last and perhaps miraculously, starting to return to normal.

[1] The state could use chronic absenteeism rates, though school attendance rates would be distorted due to the closures (during the closure, all students are considered to be in attendance).