The governor’s state of the state highlights his early literacy agenda

Last week, Governor DeWine delivered the first state of the state address of his second term.

Last week, Governor DeWine delivered the first state of the state address of his second term.

Last week, Governor DeWine delivered the first state of the state address of his second term. He covered a wide range of topics, from housing and public safety to workforce and economic development, but began his speech by pointing to the “moral imperative” of ensuring that all Ohio children are “fully educated.”

His primary focus was on early literacy and the fact that 40 percent of Ohio third grade students are not proficient in reading. He didn’t spend time explaining why this should be such cause for concern, but he didn’t need to. Research on outcomes for struggling readers is well-established. A 2012 report from the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that third graders who weren’t proficient in reading were four times as likely to drop out of high school than those who were proficient. Longitudinal analyses conducted in Ohio and elsewhere have produced similar findings. The consequences aren’t limited to academic performance, either. For the estimated 16 million Americans who are functionally illiterate, everyday activities like getting a driver’s license, reading news stories online, or voting are far more difficult than they should be.

Fortunately for Ohioans, the administration seems eager to not only shine a light on early literacy struggles, but to actually do something about them. In his recently released budget recommendations, DeWine invested $174.1 million toward improving literacy and outlined how those funds would be spent. Let’s take a look.

The strategy starts with high-quality curriculum. In his address, DeWine reminded listeners that there is a “great deal of research about how we learn to read.” And he’s right. The science of reading—the pedagogy and practices proven to effectively teach children how to read—focuses on five main components: phonics, phonemic awareness, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. Phonics, in particular, is crucial. Unfortunately, far too many schools still use curricula and materials that aren’t properly aligned with the science of reading. To fix this, DeWine has a three-step plan.

First, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) will be charged with creating a list of high-quality core curriculum and instructional materials in English language arts, as well as a list of evidence-based reading intervention programs, that are aligned with the science of reading. Second, public schools will be required to use the materials and programs that appear on this list—and only those on the list—starting in the 2024–25 school year. Unless schools apply to ODE for a waiver (which they are permitted to do on an individual student basis in certain circumstances), they are forbidden from using any curriculum, materials, or reading intervention programs that utilize the three-cueing approach, which encourages students to make predictions and use context clues to identify words. Third, DeWine has pledged to provide funding to each school to pay for curriculum based on the science of reading.

Funds will also cover the cost of professional development for teachers. Specifically, DeWine has promised that the ODE will “create professional development coursework rooted in evidence-based strategies for effective literacy instruction” and that the state will provide funding to schools to incorporate this literacy training into their classrooms. This is important for two reasons. First, although Ohio requires most teachers to pass a Foundations of Reading exam prior to receiving a teaching license and also mandates the completion of a minimum of twelve semester hours of college coursework covering topics like phonics and reading instruction, such requirements can’t—and weren’t intended to—keep current teachers up-to-date on the best strategies and approaches for teaching reading. Teachers need ongoing support, and providing them with professional development coursework meets that need. Second, by picking up the tab, the state ensures that districts and schools with tight budgets won’t have to skip out on offering critical professional development for the sake of saving a few bucks.

Last but not least, the DeWine administration has pledged that ODE will support up to 100 additional literacy coaches in schools and districts with the lowest reading proficiency. Coaches will implement the Ohio Literacy Coaching Model, which was part of the state’s 2020 plan to raise literacy achievement, and will support the use of high-quality instructional materials statewide. This is a smart move by the administration, as it’s proven effective elsewhere. Mississippi, which has improved its early literacy outcomes to such a degree that it’s been called a “miracle,” also invested in literacy coaches.

All things considered, the DeWine administration has put forth a solid plan for investing in early literacy improvements. There’s still a long way to go before these proposals become law, but the fact that early literacy occupies such a prominent part of the governor’s education agenda is worthy of celebration.

Last week, Governor Mike DeWine unveiled his state budget proposal for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. The blueprint calls for an $856 million increase in state expenditures on K–12 education by 2025 (up 8 percent compared to the $10.3 billion currently spent). It also includes a number of significant education initiatives, including three important proposals in the realm of school choice.

1. Boosting the state’s quality charter school fund

During his tenure in office, Governor DeWine has been a strong champion for high-quality public charter schools. In fact, one of his signature first-term initiatives was a new supplemental funding program for quality charters via his first budget in 2019. This innovative program provides qualifying schools with up to $1,750 in additional funding per economically disadvantaged pupil, and $1,000 for non-disadvantaged pupils. These dollars help narrow longstanding charter funding gaps, provide some of the extra resources needed for quality schools to expand, and create an incentive for lower-performing charters to improve. At present, approximately one-third of Ohio charters—117 schools serving some 39,000 students—receive these funds by meeting criteria that include earning a four- or five-star value-added rating and registering higher performance index scores than their local district for two consecutive years. In total, qualifying schools are on track to receive $54 million in FY 2023, though the per-pupil amounts are being reduced by about 20 percent to fit the fixed appropriation approved during the last budget cycle.

In his latest proposal, the governor aims to boost the high-quality fund by more than doubling the appropriation to $125 million per year. This would provide schools with $3,000 per economically disadvantaged student each year,[1] moving quality charters’ funding levels closer to parity with districts. (Charters currently receive on average roughly 70 to 75 cents on the dollar in total funding compared to their local district.) The higher funding amounts should also re-energize new school formation throughout Ohio, as quality charters gain serious capacity to expand their existing schools or launch new ones. They should make Ohio an even more attractive locale for top-notch national charter networks—something that has already occurred in the past couple years after the initial creation of the fund. All told, the governor’s proposal is great news for Ohio families and students, who will reap the benefits of having more, and better funded, quality public school options within their reach.

2. Increasing Ohio’s charter facilities allowance

Traditional districts have long had access to taxpayer funds that allow them to meet their facility needs. At a local level, districts can ask voters to pass bond and permanent improvement levies that cover facilities costs; they can also tap into the state’s main school construction grant program known as CFAP. Charters, however, don’t have local taxing authority and they aren’t eligible for CFAP. As a result, charters often make do with spartan facilities that are less conducive for the learning and enrichment opportunities that students elsewhere take for granted, and/or they have to take money from instructional activities in order to pay the mortgage or rent. In fact, an ExcelinEd analysis published last year found that Ohio only meets 18 percent of charters’ actual facility needs.

Ohio has recently taken some small steps forward in funding charter facilities, including a state budget item that provides a modest per-pupil allowance to cover building expenses. Currently, this appropriation provides $500 per pupil, a welcome amount but still far below districts’ annual spending on building operations, maintenance, and capital outlay. In his budget proposal, Governor DeWine doubles the per-pupil facility allowance to $1,000, an increase that will better ensure charter students are learning in suitable facilities.

3. Expanding EdChoice scholarship eligibility

Last but not least, Governor DeWine has proposed a significant expansion to the state’s private-school scholarship program known as EdChoice. This program offers state-funded scholarships (a.k.a., vouchers) that allow students to enroll in private schools when they either attend a low-performing school or are from low-income households. To be eligible for the income-based scholarship, families must have household incomes at or below 250 percent of the federal poverty level (presently $69,375 for a family of four). While current policy makes sure to cover Ohio’s neediest students, the income threshold still leaves out many working families. For instance, a family where dad works as a police officer and mom works as a nurse is likely to be ineligible for the assistance.

Under the governor’s new proposal, the eligibility threshold for income-based EdChoice would rise to 400 percent of the federal poverty level ($110,000 for a family of four). This would be great news for thousands of Ohio parents who prefer private school options in their local community, but still can’t afford it within their family budget. Ohio, of course, could go a step further and follow the lead of several other states—and a recent bill introduced in the Senate—and simply make scholarships universal by eliminating income limits altogether. But the substantial expansion of EdChoice proposed by the governor should be celebrated as yet another big move toward empowering all Ohio families with educational options.

* * *

As the governor’s budget heads to the General Assembly for debate, lawmakers should embrace these provisions. Hopefully, they’ll even consider building on them in various ways, such as ensuring that quality charters are funded at full parity with their local district (that’d take at least another $1,000 per pupil) or pursuing other facility supports, such as a credit enhancement program. But for now, three hearty cheers for Governor DeWine and his bold support for charter schools and private school choice.

[1] The governor’s “budget book” doesn’t specify whether the per-pupil amounts would continue to be reduced if they exceed the appropriation. More details will be in the actual legislation.

Since first taking office in 2019, Governor DeWine has consistently prioritized policies aimed at expanding and improving career-technical education (CTE). His first budget included several policies intended to give high schoolers a head start on earning industry-recognized credentials (IRCs), including an incentive program that awarded high schools with additional funds when students earned a qualifying credential. Two years later, he doubled down on IRC funding and programs like TechCred, which helps Ohioans earn technology-focused credentials and aids businesses in upskilling their employees.

Now, with his second term under way, DeWine is strengthening his focus on CTE. Consider the table below, which highlights allocations for three special CTE funding programs since 2020 and includes the governor’s budget recommendations for FY 2024 and 2025.

As the table shows, CTE spending has risen consistently during DeWine’s term, and he’s proposed further increases in his latest budget. We’ll have to wait for legislative language to get all the nitty-gritty details, but it’s likely that the funding allocated for IRCs for high school students will bolster the state’s previous efforts to incentivize credential attainment. DeWine also mentioned in his state of the state address that some career centers lack “modern, up-to-date equipment needed to teach certain courses.” He pledged to change that, so it’s reasonable to assume that’s where the money allocated for “CTE equipment” will go.

An overview of his budget recommendations also points to three additional CTE objectives. First, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) will be charged with increasing the number of in-demand career-technical programs across the state. Focusing on “in-demand” programs is important, as a recent analysis of Ohio’s K–12 industry credential landscape conducted by ExcelinEd, a national educational advocacy organization, and Lightcast, which specializes in labor market analytics, indicated significant misalignment between the credentials employers demand and those that are promoted by the state. A whopping 68 percent of credentials—314 of the 464 that appear on the state’s promoted credential list—do not have “meaningful labor market demand.” Similar misalignment was found between the credentials employers demand and those that students actually earn. Only 20 percent of the credentials earned by the graduating class of 2020 were considered in demand, and among the top fifteen credentials earned, twelve were either not demanded by employers, oversupplied, or considered to be markers of general career readiness. Hopefully, the administration is aware of these significant mismatches, and plans to require that funding only be awarded to truly in-demand CTE programs.

Second, ODE will incentivize schools and businesses to offer work-based learning (WBL) opportunities to 10,000 students across the state. Ohio previously laid a solid foundation by requiring ODE to develop a framework for schools to grant high school credit to students who demonstrate subject competency through WBL. The state also established a tax credit for employers who offer WBL experiences. But there’s still plenty of untapped potential—like finally investing in youth apprenticeships—and it appears that this funding is aimed at realizing those possibilities.

Third, ODE will work to strengthen Business Advisory Councils, which are locally focused partnerships aimed at getting education and business leaders to work together to make schools more responsive to workforce needs and to ensure that students have relevant learning experiences (like WBL). The budget overview indicates the governor is particularly interested in providing additional support for “high-quality partnerships.” Given that K–12 schools, higher education institutions, and employers historically operate in silos—and the potential that high-quality collaborative efforts have to positively impact students, job seekers, and the community—increased support from the state could prove beneficial.

***

Governor DeWine’s commitment to CTE shouldn’t surprise anyone. His administration was laser-focused on workforce development and career pathways during his first term, and the initiatives he championed were both successful and popular. But even though his renewed focus isn’t surprising, it’s still worthy of praise. Here’s hoping the legislature follows the governor’s lead and not only approves these investments, but builds on them.

In anticipation of debates about school funding in the coming months, I recently began a series on Ohio’s new school funding formula. The previous piece presented a high-level overview of the old and new funding formulas, the mechanism that determines state allocations to districts and charter schools. This piece will start a deeper dive into some of the key features of the new formula. Here, we’ll look at the “base cost” model, one of its most distinctive elements and the source of its higher cost (an estimated $2 billion in additional state spending—if fully funded—or a roughly 20 percent increase).

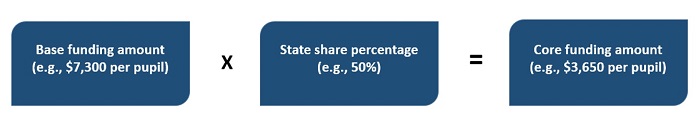

Under both the old and new formulas, the bulk of state formula aid is delivered through a core funding component. Each district’s core amount is calculated using the basic equation displayed below.[1] On the right side, the base amount could be seen as the minimum funding that the state presumes is necessary to support a typical student’s education. Meanwhile, the state share percentage is an “equalizing” mechanism that accounts for districts’ varying capacities to raise local revenue, including a state-required 2 percent property tax that contributes to the base. Higher wealth districts have smaller state shares, and vice-versa for poorer districts.

Things get more complicated after that, especially under the new formula. Let’s start by looking at the base amount (we’ll discuss the state share next time).

Under the old formula, the state simply set a “fixed” base that applied to all districts and charter schools. That approach had the benefit of simplicity and transparency, and lawmakers could easily adjust the base to increase or, if necessary, decrease education expenditures each year. Opponents of the fixed base argued that the number was arbitrary—and, in their view, at levels that didn’t cover the costs to educate the average student. The new formula seeks to address these concerns by implementing a set of calculations—called a “base cost model”—that yields a “variable” base amount that differs for each district.

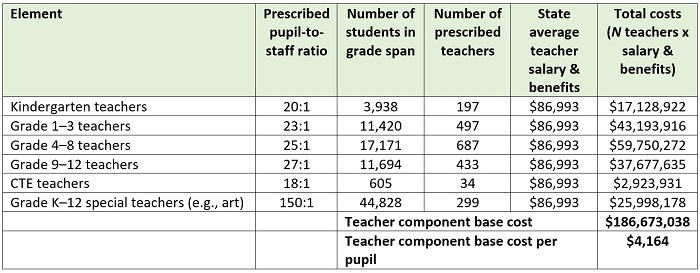

This model uses staff-to-pupil ratios, statewide average salary data, and other expenditure data on things like supplies and building operations to “cost out” the “inputs” of a typical student’s education. Table 2 illustrates the teacher-cost calculations using FY 2023 data for Columbus City Schools. Note that teachers are just one dimension of the base cost model; other “inputs” include—among other items—support and administrative staff and their average salaries.

Table 1: Illustration of teacher component calculations in Ohio’s base cost formula

At this point, we must remember that there is no scientific way to determine the cost to educate a typical student (and to what, if any, educational standard). Yet there is some appeal, largely political, in attempting to cost out the inputs of a student’s education. Rather than being accused of setting an arbitrary base, this approach allows legislators to “show their work.” That being said, the framework also poses significant problems for the state. Let’s take a look.

Problem 1: The base cost model drives much higher funding amounts, leading to a statewide “cap.” Under the old formula, the most recent base was $6,020 per pupil in FY 2021. Even at that amount, the state didn’t fully fund its formula, “capping” some districts’ state funding allocations—i.e., not sending them the full amounts prescribed under the formula. Between 2016–18, caps withheld about $500 million per year to roughly 175 districts. The new formula’s statewide average base is $7,352 per pupil, thus explaining its approximately $2 billion per year cost above and beyond current state expenditures (good for an additional $1,250 per pupil average statewide). At such a price tag, legislators declined to fully implement the new formula and instead phased in the additional spending, with 33 percent of the added expense being implemented by FY 2023. The phase-in, however, represents a statewide “cap” of sorts—this time, on all districts and charter schools. One of the goals of the new formula was to get away from caps and fund schools strictly according to the formula. But the costs generated by the new model effectively create another type of cap and thus Ohio still isn’t truly following its own formula.

Problem 2: Updating salary “inputs” will generate new, additional costs for the state. The challenge of fully funding the new formula is doubly difficult because the state is currently using FY 2018 average salaries to calculate base amounts. Lawmakers will inevitably face political pressure—perhaps even this year—to update these salaries, creating an even bigger hole to fill. On the teacher salary front, for instance, the statewide average in 2018 was $62,353 but rose to $67,654 in 2022 (up 8.5 percent). Those salaries could escalate even faster in 2023 and 2024 as schools spend billions in federal Covid-relief money, a decent portion of which is likely going into salaries, in part to keep up with rising inflation. Local revenues, and employee salaries in turn, could also rise if districts are able to raise taxes at the ballot box. When and if state legislators update the salary and benefit data, base amounts will soar, causing an increase to the overall cost of the formula. That leaves open questions about whether the state can ever truly afford this formula.

Problem 3: Guaranteed staffing minimums that wildly inflate the base amounts of small districts. For certain positions, the base cost model prescribes a minimum staffing number that deviates from the “normal” calculations. For instance, all districts receive at least six special teachers (e.g., art, music, or gym), even if the ratios would otherwise yield lower numbers. Consider a district with 600 students. Normally, the formula would prescribe four special teachers at a 150:1 student to teacher ratio. But instead of that number, the district receives six special teachers along with their salaries and benefits. Other minimums also apply for student wellness, fiscal support, and a few other staff positions.

Table 2 shows the result. Districts with fewer than roughly 700 students—representing about one-sixth of Ohio districts—have base amounts of more than $8,000 per pupil. A handful of extremely small districts receive incredibly high bases above $10,000 per pupil. Charter schools, despite their comparable size to a small district, do not receive such staffing minimums.

Table 2: Base cost per pupil by district enrollment size, FY 2023

There are several problems with this policy. First, it creates an unfair system that gives special treatment to small districts, thus contradicting one of the purported aims of the overhaul—to create a “fair” system that treats all schools evenhandedly. Second, it discourages districts from operating efficiently. Rather than assuming that a 600-student district absolutely needs six special teachers or two fiscal support staff, the state should be encouraging it to pursue shared services and staff. Third, one might ask whether it actually makes sense to assume that it costs 25 to 50 percent more to educate a typical student in small districts. It’s possible that they actually face lower costs of living or need fewer expensive supports than larger districts serving students in metropolitan areas. Fourth, the minimums add unnecessary costs to the formula, making it more expensive than it needs to be.

State lawmakers have two options to address these issues in the base cost formula.

* * *

Like a game of whack-a-mole, the new formula’s base cost model tries to fix a perceived problem—the lack of an explicit link between the base amount and costs—but it also creates several other problems in turn. How state legislators address the base cost dimension of the formula will be one thing to watch in the coming months.

[1] This equation applies only to districts. Because charter schools do not receive local funds, the state share is not applied.

Teacher shortages have been a hot topic over the last few years. Research shows they vary from place to place, and Ohio currently lacks the data to confirm how widespread and significant they are, but there’s no denying that for some districts and schools, finding enough quality teachers is an annual hardship.

To help these schools, state and local leaders will have to work together to solve a plethora of problems that fall under two main umbrellas: recruitment and retention. Most Americans are likely familiar with retention issues, which include understandable complaints from educators about low pay, stagnant retirement benefits, and frustrating working conditions.

But recruitment issues are just as much of a factor. Consider a 2018 brief published by ACT, in which researchers used survey data to examine the responses of students who were “very” or “fairly” sure about their college major. They found that, from 2007 to 2017, high schoolers’ interest in teaching decreased significantly. This declining interest seems to have carried into the real world; the Center for American Progress indicates that enrollment in teacher-preparation programs nationally fell by more than one-third from 2010 to 2018. Ohio posted a decline of nearly 50 percent.

These are worrisome numbers on their own, but they’re even more troubling when we take into account that the teaching profession is traditionally unfriendly to career changers. Without a bachelor’s or master’s degree in education, and the time and money required to obtain them, it’s difficult for even the most committed prospective teachers to get licensed in Ohio. As a result, schools face a double whammy: Not only are there fewer teachers coming out of colleges of education, there aren’t many coming via alternative routes either.

Grow Your Own (GYO) programs can help. These programs are appropriately named because they focus teacher recruitment efforts on people living in the local community: paraprofessionals or substitute teachers who already work in schools, college graduates who are looking to change careers, and high school students who are interested in education as a future career. They are typically partnerships between local school districts, higher education, and community-based organizations or nonprofits that work together to train prospective teachers and get them certified. And while they can take the form of teacher residencies—programs that embed teacher candidates into a school for clinical training while also providing coursework and financial compensation—they don’t have to.

GYO programs offer a host of potential benefits. The most obvious is that they can help replenish the teacher pipeline by recruiting and training more educators, especially in hard-to-staff subjects or grade levels. Their focus on local communities is also a benefit, as research indicates that many teachers prefer working in or around the communities in which they grew up. Most importantly, though, GYO programs can help diversify the teacher workforce, which can improve a wide range of student outcomes. A recent study of six GYO programs that were designed and administered by TNTP indicates that they added seventy-four more teachers of color than might have otherwise been hired by the six participating districts.

The good news is that Ohio has already dipped its toes in the GYO program pool. Sinclair Community College and Mad River Local Schools have developed a teacher academy that allows high school students interested in becoming teachers to get a sneak peek into the profession and earn college credit through College Credit Plus. Lorain County Community College offers something similar, and several program alumni are already teachers. A state-established taskforce charged with examining how Ohio could diversify its educator workforce has recommend expanding GYO programs. And Ohio’s Human Capital Resource Center has an entire page devoted to doing so, including toolkits for how to design programs and how to address barriers.

To truly reap the potential benefits of GYO programs, though, state leaders need to do more. Here are two ideas.

1. Include a revised version of House Bill 667 in the state budget

House Bill 667, which was proposed last spring but not passed, sought to establish the Grow Your Own Teacher College Scholarship Program. This program proposed four-year scholarships worth up to $7,500 per year to eligible high school students and district employees who committed to teaching in a qualifying school—one that was operated by the same district from which they graduated or where they were employed, and where at least 50 percent of students were eligible for free or reduced-priced lunch. Scholarship recipients would be required to teach in these schools within six years of completing a teacher preparation program, and for a duration of at least four years. The bill appropriated $25 million for FY 2022 and 2023, and specified that teacher candidates had to attend a traditional teacher training program, either at a state or private, nonprofit college or university.

The underlying idea behind HB 667 is a good one. It’s not cheap to become a teacher, and easing the financial burden for high schoolers and career changers could bolster the teacher pipeline. Requiring scholarship recipients to teach in districts that they graduated from or worked for is also firmly in line with the unique mission of GYO programs. But by limiting the scholarship to candidates who attend traditional teacher training programs, the bill eliminated the possibility that high-quality alternative programs—like TNTP, which administered the GYO programs that were found to have increased diversity in several districts’ hiring—could contribute.

To be fair, there aren’t many alternative teacher preparation programs currently operating in Ohio. Teach For America (TFA) is the only sizable one, and that’s likely because state law includes a provision that grants TFA participants traditional teacher licenses (known as resident educator licenses), even though they’ve been trained via an alternative program. If state law allowed other alternative programs—rigorous, high-quality ones with solid track records of improving student outcomes—to enjoy the same privilege, then GYO programs might be a lot more prevalent than they are now.

With these issues in mind, state lawmakers should do a few things. First, incorporate the bill language from HB 667 into the state budget. Second, amend that language to specify that teacher candidates who attend state-approved alternative teacher preparation programs are also eligible for the scholarship. And third, establish a process for alternative training programs—like those who run effective GYO programs in other states—to gain approval through the Ohio Department of Higher Education to grant their participants resident educator licenses. Revising the law in this way would encourage highly-effective training programs in other states to expand to Ohio, and would open the door for schools of all stripes to create their own GYO programs.

2. Leverage current law to create a statewide initiative

Current law permits the department of education to award grants to schools to assist in various innovation efforts, including “the implementation of ‘grow your own’ recruitment strategies.” It also allows for “the development and implementation of a partnership with teacher preparation programs” that would aid in attracting teachers who are “qualified to teach in shortage areas.” Both these provisions make it possible for state leaders to heavily invest in an initiative that supports GYO programs. Unfortunately, the state has largely left that work to local districts. They’ve done a decent enough job, but if Ohio wants to capitalize on the potential of these programs, state leaders need to do more.

Other states offer plenty of examples. Illinois, for instance, has funded a statewide GYO initiative, Grow Your Own Illinois (GYO-IL), since the late 2000s. The most recent legislative report available on its website indicates that, in 2021, the program served 257 prospective teacher candidates across Illinois, and that two-thirds of those candidates identified as teachers of color. In Tennessee, state leaders used federal Covid relief funding to establish a statewide GYO competitive grant program. In total, it’s awarded $6.5 million to grow your own grants promising to “create pathways to become a teacher for free.” Tennessee has also given the go ahead to several preparation programs to offer teacher apprenticeships as part of its GYO initiative. Ohio could follow in the footsteps of either of these states, or it could create its own program from the ground up. Either way, schools and students would benefit.

***

GYO programs aren’t a silver bullet for all of Ohio’s teacher shortage woes. But effectively cultivating GYO programs could produce an influx of new teachers that schools didn’t have before. Even better, it could help diversify the profession and improve student outcomes. That seems like a win-win worthy of investment.

English learners (ELs) are students whose native language is other than English and who score below proficient on an English proficiency test. There were more than 5 million ELs in U.S. schools in 2019, and millions of dollars in federal, state, and local funds are spent each year in an effort to help them reach proficiency and shed their EL classification. While specific language instruction is most of what’s done to reach that goal, these young people are not just learning language, but also math, science, social studies and (yes) English with their peers. Could the effectiveness of their general education teachers have an impact on the speed with which ELs reach proficiency, as well? A new study aims to find out.

SRI International researcher Ela Joshi uses administrative data from the Tennessee Department of Education covering the school years 2006–07 to 2014–15—a dataset that includes student and teacher demographics, students’ annual EL status, measures of teacher effectiveness from the state’s evaluation system, student-teacher linkages, and staffing details—as well as EL students’ scores on end-of-year tests. Her sample comprises over 13,000 Volunteer State students who began kindergarten between 2006 and 2012 and who were continuously enrolled through third grade. Most importantly, all were still classified as ELs at the start of third grade, and all were linked with specific EL teachers and specific general education teachers at the elementary level or specific general education English teachers in middle school.

Joshi uses discrete-time survival analysis to estimate the relationship between ELs’ likelihood of reaching English-language proficiency in each year between third and eighth grade, as well as specific characteristics of their general education teachers—such as demographics and effectiveness—that may impact that trajectory. Joshi tests five separate measures of teacher effectiveness, all of which use either state value-added (TVAAS) or teacher observation scores: a continuous three-year composite value added score; the TVAAS level of effectiveness; a continuous average observation score; observation quartiles; and a summary level of effectiveness (LOE) score, which combines TVAAS, observation data, and student surveys.

Overall, ELs assigned to effective or highly-effective general education teachers (as rated by any of the five effectiveness measures) were 17 to 50 percent more likely to reach English-language proficiency in a given year, compared to their peers assigned to less-effective general education teachers. However, robustness checks on these findings began to whittle away at the observed impacts. In the end, teacher effectiveness based on TVAAS scores and observation scores were the strongest predictors of student success (10 to 31 percent more likely than their peers to reach proficiency), the others showing little to no impact. Joshi discusses a number of possible mechanisms that may be at work, all of which boil down to “great teachers are great teachers to many different types of students.”

As to demographics, a ten-year increase in teacher experience was associated with a 5 to 8 percent increase in the probability of a student reaching proficiency in a given year, and assignment to a general education teacher of color was associated with an 11 percent increase in the probability of reaching proficiency. The latter finding could be connected to the benefits of a sympathetic set of academic perceptions and attitudes between teacher and student observed in other research, but the former seems to be more of the “great teacher” effect.

All of this combines to point out the obvious: To reach the highest possible level of achievement, all students need their teachers to be of the highest possible quality. Unfortunately, how to make that happen is far less obvious.

SOURCE: Ela Joshi, “Unpacking the Relationship Between Classroom Teacher Characteristics and Time to English Learner Reclassification,” American Educational Research Association AERA Journal (January 2023).

What does it cost to retain a less-than-proficient student and provide him or her with remediation and additional support? In a new research brief, Boston University professor Marcus Winters says the amount is lower than previous analysts, including himself, have estimated and goes on to show why.

Key to Winters’s framework is that cost accrues both to the taxpayers who fund the additional time and work and to the students who are held back, as they are likely delayed from entering the job market because of their extra time in school. Winters asserts that previous analyses did not account for these timeframes properly, as taxpayers don’t fund extra education for a retained student until she stays in school beyond her expected high school graduation date. In other words, a youngster who repeats third grade was always going to be on the school’s roster that second year, but as a fourth grader rather than a third grader. Although it is possible that she will remain a grade level behind for eight more years and thus require that extra year of taxpayer-funded education, data suggest that one of several other outcomes is likely to occur before then: catching up and rejoining her previous grade cohort, leaving that system for another (such as a private school or an out-of-state district), or dropping out of school entirely.

Laying aside the relative undesirability of some of these outcomes, the math speaks for itself. Allocating a full year of additional funding as a necessary cost of retention is incorrect. The same goes for the cost of lost wages to the student herself. Winters and other analysts include not only the first year of lost wages (due to a delayed grade twelve) but also multiple additional years of decreased raises afterward due to delayed entry. Even assuming that catching up with wage growth is impossible, a retained student is still more likely to enter the workforce—one way or the other—less than a year behind expectation. Calculations must be made accordingly.

To illustrate, Winters returns to previously published analyses of Florida’s third grade retention policies. A study that looked at the first cohort of third graders retained in Florida in 2002–03, on which Winters was an analyst, indicated clearly that students who remained in their schools through graduation were only delayed by 62.8 percent of a year. Yet the cost calculations assumed a full year’s delay. Rerunning those numbers with the proper delay factor—and even including the full reported cost of interventions intended to boost student achievement—yields a taxpayer cost 34 percent lower than originally estimated. Lost wages were similarly overestimated in the previous analyses.

While there are adjunct costs to holding students back, the benefits could easily outweigh those costs. Yes, a retained student might spend a few less months in the labor market, but the career earnings potential of being able to read fluently (as opposed to being illiterate) should easily surpass those fleeting losses. That’s what retention—and robust support—aims to do for students who are struggling to read.

Retention policies should go hand in hand with a robust set of supports in place to make sure that those who are off track can make up ground as quickly and simply as possible. While there are adjunct costs to holding students back, these have been exaggerated in previous research and can be minimized even further by a focus on boosting student achievement. Future discussions of the merits of retention policies should proceed from this more realistic assessment.

SOURCE: Marcus A. Winters, “The Cost of Retention Under a Test-Based Promotion Policy for Taxpayers and Students,” American Education Research Association (AERA) Journal (December 2022).