How to make Ohio’s state test results more useful to parents

Earlier this month, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) sent family score reports to school districts.

Earlier this month, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) sent family score reports to school districts.

Earlier this month, the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) sent family score reports to school districts. These reports, which districts are now supposed to distribute to parents, offer detailed information about how their children performed on state assessments this spring—especially crucial data as parents seek to understand where their child stands in the wake of Covid-related disruptions. For many moms and dads, these reports reinforce what they saw on their child’s report cards during the year. But for others—in an era of grade inflation—these reports might offer a “second opinion” that cause them to rethink their child’s learning needs.

Overall, Ohio currently has a decent system in place for communicating results, but it could improve the reporting to parents in two significant ways: expediting the release score reports, and improving their presentation.

Expediting test-score reports

In the age of online assessment, one might think that parents receive results shortly after their children take the exams. But that’s not true. Most parents have to wait months before they see test scores—too late, in many cases, to seek summer supports or plan for the coming fall. That’s not acceptable in normal times, but it’s particularly worrisome this year, as more parents than usual explore ways to help their children recovery after the pandemic.

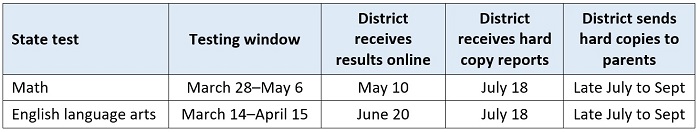

Table 1 displays the timeline for this spring’s state exams. Students took math and English language arts (ELA) exams sometime during the mid-March to early May testing windows. School districts receive math results in an online reporting system rather promptly—about a month or so after testing—but they wait longer for ELA (likely due to grading of writing sections). However, just because schools can access results then doesn’t mean parents can. While some districts proactively post results in their parent portals shortly after online receipt, others leave parents waiting for hard copies. Printed versions didn’t arrive in district mailboxes until July 18. After that, it’s unclear how and when districts decide to send reports home to parents. Schools could mail them right away, but others might delay until class is back in session. Some may even send reports home in kids’ backpacks where the information can get lost in the flood of other back-to-school paperwork.

Table 1: Spring 2022 state testing schedule

Source: Ohio Department of Education, 2021–2022 Testing Dates.

State policymakers have some options to speed this process. One is to create a statewide online portal, akin to what Texas has developed, where parents can register and get their child’s results directly from ODE or the assessment vendor—a service that does not currently exist. (A voluntary signup option is likely the only way to communicate results directly to parents, as there is no statewide “roster” with contact info.) Another alternative is to set clear deadlines for distribution. Legislators could insist that ODE send printed copies to districts by June 15 and require districts to mail them home to parents by June 30. A final legislative possibility is to require districts to post student test scores to parent portals—if they have one—as soon as they are made available digitally.

Strengthening report content

Surveys from Learning Heroes find that the vast majority of U.S. parents—nine in ten—believe their child is doing math or reading at or above grade level. Many are undoubtedly influenced by the high marks that come home on their child’s report card: Upwards of 80 percent say their children receive mostly A’s and B’s. The assessment data, however, reveal fewer students achieving at such high levels. In Ohio, roughly 55 to 65 percent of students meet the state’s proficiency standards and even fewer achieve marks on exams that indicate being on track for college (about two in five).

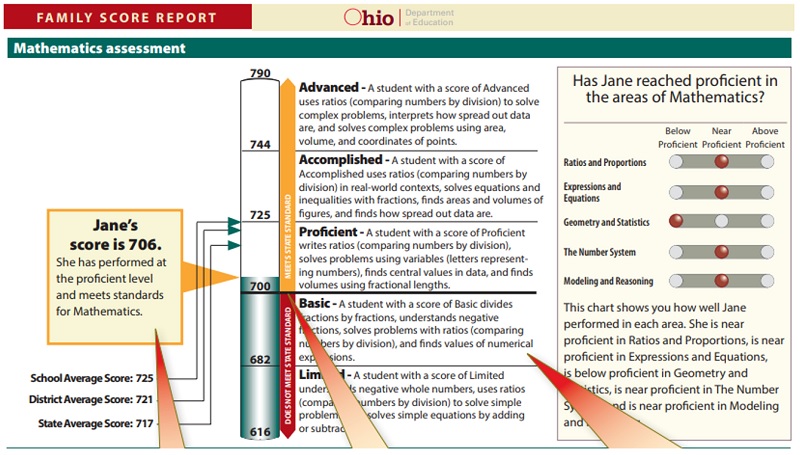

Ohio needs to make sure that parents get an honest, complete picture of their child’s academic performance. But what is on them? Figure 1 displays the key information on a student’s test-score report in math. The basic data are a student’s scaled score and the corresponding achievement level. In isolation, the scaled score will mean little to parents (706 in this fictional example), but the translation into an achievement level (proficient) provides more context about a student’s academic standing. Also valuable are the comparisons of a child’s scaled score to the local school and district average, and the statewide average. A breakdown of a student’s results on the specific areas of the exam also appears, allowing parents to better pinpoint their child’s strengths and weaknesses.

Figure 1: Illustration of a student’s test score report

Source: Ohio Department of Education.

While the basics are there, two pieces of information would offer parents a clearer picture of their child’s academic standing.

First, current score reports don’t provide a longitudinal picture of student performance over time. Parents only get single-year snapshots, so unless they keep historical records, they don’t get an indication of their child’s progress. To fill this gap, the state should display a student’s statewide percentile ranking over time and changes in the achievement level for the tested subject. Previous years’ scaled scores could also be displayed, but those may not be comparable from one grade to the next.

Second, Ohio’s reports don’t provide a clear enough signal about whether a child is on-track for success in college. Achieving the proficient mark—which is considered “passing”—could mislead parents into thinking their child is on pace to graduate ready for college. But buried within the fine print of the score reports is a note that reaching the accomplished level of performance—one level above proficient—actually indicates a student is on track. This distinction must be more than a footnote. Ohio could also more clearly communicate college readiness by including projections of a student’s ACT or SAT score starting in middle school. SAS, the analytics firm that calculates value-added scores, already does these projections, so all the state needs to do is include them on test-score reports. To be sure, higher education isn’t the goal for everyone, but transparent information about readiness should be available to all.

***

Ohio parents make hundreds of decisions—some big, others small—on behalf of their children. Do we spend more of our household budget on afterschool tutoring or summer school? Do we enroll our child in this or that enrichment program? Which elective courses or programs at school should we be encouraging? No single report will be able to answer every question, but the more information parents have about their child’s academic progress, the better. Other states, with assistance from parent-focused groups, have stepped up their game in communicating results to parents. Ohio, too, can make sure that parents get information that helps them support their children.

Arizona, long one of the nation’s trailblazers in the school-choice movement, recently expanded its education savings account (ESA) program to ensure that all students—regardless of income or where they attend school—are eligible for state dollars that can be used for private school tuition and other educational expenses. Alongside West Virginia, Arizona is now home to one of the nation’s two “universal” private school choice programs—programs in which every school-age child is eligible to participate.

Ohio already has a fairly expansive choice program, but it hasn’t quite reached this lofty plateau. The Buckeye State’s five scholarship programs include the Cleveland scholarship, performance-based EdChoice, income-based EdChoice, and two for students with disabilities. Taken together, these programs make about half of Ohio K–12 students eligible for a scholarship, and roughly 77,000 students (or 5 percent of Ohio students) participate.

Over the years, state legislators have taken many steps to get to this point. But should Ohio lawmakers take the leap to a universal school choice program?

Among choice advocates there is some divergence of opinion about whether private school scholarship or ESA-style programs should be “means tested” or “open to all.” One of the giants in the movement, Howard Fuller, for instance, contends that universal programs might lose their focus on serving the children most in need of educational options. Other prominent advocates such as Robert Enlow and Lindsey Burke argue in favor of universal choice on both pragmatic grounds—creating a “bigger tent,” which would help politically—and to give all parents more options when public schools aren’t to their liking. (Needless to say, choice critics don’t support either approach.)

My view is that a universal private school choice program is the right way to go for Ohio. Here’s why.

Reason 1: Empowers all parents

As the unit most responsible for the upbringing of children, parents have an inherent right to direct their child’s education. This basic premise was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1925 landmark Pierce v. Sisters decision about whether a state could ban private education. The Court wrote: “Those who nurture him [the child] and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognize and prepare him for additional obligations.”

When states expand schooling options, they strengthen this right. While many parents are satisfied with their local public schools, others prefer something different for their child. Some have children with special academic or artistic talents and might seek private schools that can cultivate those gifts. Others desire private schools because of their religious affiliation and faith-based models. Still others value the smaller, more familial settings offered by many private schools.

Unfortunately, not all families have the financial capacity to access their first-choice school and must settle for a less-agreeable option. Ohio has taken great strides to unlock private school opportunities for its neediest parents, but private schools are still a stretch for most middle-class parents. Universal choice would give every family the opportunity to choose which school will shape the heart and mind of their child.

Reason 2: Encourages healthy competition

Historically, districts have enjoyed a “territorial exclusive franchise” (i.e., monopoly) to educate children within their borders. But with the rise of private school choice programs (and public charter schools, too), districts are more strongly encouraged to meet the needs of families and students. Indeed, the research evidence indicates that they do respond to incentives, as choice programs around the nation and in Ohio are linked to higher district performance. Expanding scholarship eligibility to all students would create healthy competition in any area of Ohio with private school options—a win-win for parents and students in both types of school systems.

Reason 3: Fairer to taxpaying parents

As all Ohioans know, the state and local school districts levy significant taxes—sales, income, and property being the largest—on citizens to support education. Private school parents pay their fair share, even though they receive educational benefits that are nowhere near congruent to what they pay in taxes. As a result, these families “double pay” for education—once through taxes and again through tuition—and that’s unfair.

Critics often complain that private school parents should pay out of pocket because not everyone approves of private (sometimes religious) education. But that argument can be reversed, as neither do public schools enjoy unanimous approval. Recent polling from Gallup shows that confidence in U.S. public schools has sagged to near all-time lows. As is well known, the teachers unions, which represent the vast majority of public school teachers, regularly promote progressive politics. In the end, the fairest approach is to adhere to the adage “fund students, not systems.” Universal choice follows this concept, with taxpayer funds underwriting all students’ educations, regardless of the choice (public or private) their parents make.

Reason 4: Reduces administrative paperwork

In a “means-tested” program, state employees must create an income-verification process whereby parents submit paperwork and accuracy is verified. On the other side, parents have to dig up tax forms, W-2s, or other documents and submit them to the state. This is not only time-consuming for parents, but it could also discourage participation among those concerned with privacy or lacking requisite documents. Complications could also emerge about what precisely constitutes “household income.” (Does a student’s summer-job earnings count? What about unemployment compensation?) Those types of situations are likely sorted out on a case-by-case basis, adding to the administrative burden. A universal choice program would require less bureaucracy, as parents need only prove they are an Ohio resident and have a school-aged child.

Reason 5: Avoids any stigma associated with a targeted program

Universal public programs avoid stigmatizing individuals or families who receive the benefits. Advocates of universally subsidized school meals, for instance, have long argued that such a policy would eliminate concerns about lunch-room condescension. Because Ohio’s scholarship programs currently target less advantaged families, there is some risk of stigmatizing students who use them. A universal choice program would eliminate any negative connotations with participation, as children from all backgrounds would be eligible for—and use—the public benefit.

Reason 6: Makes Ohio an even better state to raise a family

We all know that Ohio is already a terrific state to raise a family, but a universal choice program would up the ante and could even draw the attention of out-of-staters. Survey data consistently show that parents express strong interest in private school options. With only Arizona and West Virginia boasting a universal choice program, Ohio would be a standout as a parent-friendly destination—especially for those with an interest in private school options. While picking up and moving isn’t inexpensive, millions of families migrate from state to state each year, and with remote work becoming more prevalent, more may consider doing so in the coming years. States often promote tax advantages and other amenities to attract families and businesses. And for good reason. Migration increases economic activity (and tax revenues), and that’s a win for everyone. A universal choice program would be another arrow in the quiver for the Buckeye State in this interstate competition.

* * *

Nearly two years ago, shortly after Ohio lawmakers passed a significant expansion of the state’s scholarship programs, the Wall Street Journal’s editorial board trumpeted “A Buckeye Voucher Victory.” It was certainly that. But there remains more to be won in terms of helping all Ohio families gain access to their top choice of schools. With a universal scholarship program, the state would put the whole gamut of educational options within the reach of every parent in the state.

In late June, the national educational advocacy organization ExcelinEd published a comprehensive early literacy guide for state policymakers. The guide, which was developed alongside members of the organization’s Early Literacy Network, outlines best practices and strategies that have been successful in other states’ efforts to improve reading outcomes. The timing couldn’t be better, as Ohio policymakers are mulling changes to our early literacy laws. And while there are plenty of worthwhile policy suggestions within the guide, here’s a look at three that Ohio leaders should pay special attention to.

1. Offer better support to teachers and administrators

Research is clear that, when it comes to students’ academic performance, teachers matter most among school-related factors. If Ohio wants to improve early literacy outcomes, every child needs access to an effective teacher—and to be effective, every teacher needs to be well-versed in the science of reading.

Ohio is already on the right track. State law requires educators who teach grades pre-K–9, as well as intervention specialists, to pass Ohio’s Foundations of Reading exam prior to receiving a teaching license. Ohio Administrative Code also requires the completion of a minimum of twelve semester hours of college coursework covering topics like phonics, phonemic awareness, reading instruction, assessment, and remediation. Ohio’s efforts to align teacher preparation programs with the science of reading are even highlighted by ExcelinEd as a model for other states.

But pre-service training isn’t the only training that matters. Classroom teachers need ongoing and personalized support that won’t break the bank, and ExcelinEd’s literacy guide spotlights two states that Ohio could use as models. First is the Cornhusker State. During the 2020–21 school year, the Nebraska Department of Education partnered with TNTP to virtually host a professional development series for teachers that focused on the science of reading. The four-part series offered professional learning sessions on phonological awareness and phonics, knowledge and vocabulary, comprehension and fluency, and data analysis, as well as corresponding community of practice sessions that provided a more in-depth look at implementation. Professional learning sessions were recorded and made available to teachers who were unable to attend.

To be clear, Ohio does provide helpful online resources for teachers. The Ohio Department of Education (ODE) has a website early learning professional development, a “literacy academy,” and a series of videos on the nuts and bolts of Reading Improvement and Monitoring Plans. But the state doesn’t appear to offer in-depth professional development opportunities that focus solely on the science of reading—or even early literacy in general—to current teachers. That should change. Ohio policymakers could take a page out of Nebraska’s book and partner with a reputable organization like TNTP to make it happen. Or they could charge the state’s fifty-one educational service centers with developing in-depth training sessions that are rooted in the science of reading and available to all elementary teachers free of charge. Either way, it’s critical for state leaders to ensure that current classroom teachers have access to free learning opportunities that will keep them up to date on the latest research and best practices and provide opportunities to collaborate with other educators.

The second spotlight state is Mississippi. ExcelinEd had its pick of policies to highlight from the Magnolia State, as it’s made substantial academic progress over the last decade, especially in early literacy. In fourth grade reading gains on NAEP, Mississippi ranked second of all states from 2009 to 2019 and first from 2017 to 2019. State test scores have also steadily improved, a clear indicator that NAEP growth isn’t just a fluke. Recently retired state superintendent Carey Wright attributed the state’s improvement to a “laser-like focus on literacy” that included increased professional development for elementary teachers and literacy coaching.

ExcelinEd opted to home in on Mississippi’s use of literacy coaches, perhaps because Florida—another state with solid early literacy outcomes—also uses them. In Mississippi, literacy coaches are provided each year to identified schools, with varying levels of support based on “data and sustainable achievement over time.” Ohio would be wise to invest in this kind of consistent, on-site support for educators. Like Mississippi, Ohio could sidestep a potential staffing shortage by limiting literacy coaching to certain schools—perhaps those that rank in the bottom 10 percent of the early literacy component on state report cards. Coaches in these schools could work closely with teachers to facilitate training that’s based on the science of reading, model evidence-based instructional strategies and data-driven best practices, and observe lessons to provide immediate feedback.

2. Take advantage of out-of-school time

For struggling readers, time is critical. They need as much time as possible with highly effective teachers and well-trained tutors, but there are only so many hours in a school day. Those hours often aren’t enough, so it’s crucial for students to have access to intervention efforts before and after school, as well as during the summer months.

ExcelinEd spotlights several states as examples for how to capitalize on out-of-school time with regard to early literacy. Michigan offers a grant that provides nearly $20 million to districts to fund additional instructional time for pre-K–3 students who have been identified as needing additional reading support and intervention. And in Tennessee, legislation passed in 2021 required districts to implement extended learning programs as a way of addressing pandemic-caused learning loss. Tennessee requires schools to offer seats in these programs to “priority” students first, and while the definition of priority varies depending on the program, it includes students who scored below proficient on state exams in reading.

The Buckeye State has already devoted plenty of funding toward leveraging out-of-school time. For example, the Summer Learning and Afterschool Opportunities Grant is a competitive grant program designed to fund partnerships between schools and community-based organizations to establish or expand afterschool programs, as well as summer learning and enrichment programs. In late April, ODE announced that 161 community-based partners would be awarded $89 million to implement evidence-based programs designed to meet the needs of students who “experienced disruptions to learning and did not engage consistently in school during the pandemic.” Given that there’s still ground to be made up on learning loss, this was a wise investment. But it would also be smart for Ohio to establish a permanent, early-literacy version of this grant program. Interested districts and schools (and perhaps libraries) could apply for funds to pay for reading intervention programs offered before and after school, or for summer reading camps.

3. Hold the line on retention

Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee has been the law of the land since 2012. Several of the guarantee’s components—such as identifying struggling readers as early as kindergarten or creating reading improvement plans for identified students—enjoy broad support. But the Guarantee’s requirement that schools retain students who can’t read proficiently by third grade is more controversial.

Critics argue that holding students back fails to help them and may even cause harm. But as ExcelinEd’s guide notes, there’s a trove of data that challenges that claim. A 2017 Florida study using regression discontinuity found that retention in third grade increased students’ high school GPAs, led them to take fewer remedial courses, and had no negative impact on graduation. A 2018 study on the costs and benefits of test-based promotion in Florida found that the threat of retention led to statistically significant and substantial increases in math and reading performance within third grade. And a 2020 brief found that third grade test-based promotion policies in Florida and Arizona led to statistically significant and meaningful average test-score improvement within third grade even before the policy retained any students. Florida and Arizona aren’t the only states that have seen improved outcomes thanks to a retention policy, either. Mississippi—which, as noted earlier, has had impressive NAEP reading gains over the past decade—implemented the Literacy-Based Promotion Act in 2013. Among myriad other interventions, students who do not score proficient or above the lowest two achievement levels on state tests are retained.

Ohio has a long history of sidestepping politically unpopular policies that seek to improve student outcomes. But history doesn’t have to repeat itself. Ohio lawmakers can and should recognize that retention is backed by solid research, and that students who aren’t able to read proficiently by the end of third grade need more time to catch up with their peers. Retention coupled with intensive support can help kids become lifelong skilled readers.

***

As state policymakers search for ways to improve early literacy and student outcomes, it’s important to consider rigorous research and evidence of what’s worked in other states. ExcelinEd’s recent brief shines a spotlight on both, and the recommendations included within—and outlined above—would be a great place for Ohio leaders to start.

The career services office is a necessary stop on any good college campus tour, as it offers prospective students a sneak peek at all the help the staff within can provide—resume writing, mentors in many different employment fields, interview prep, job fairs, and much more. Those services are especially important for community colleges, as they are key players in current efforts to boost postsecondary attainment and grow the workforce in many specific industries. A new report from the RAND Corporation throws open the office doors to examine how current career services and industry partnerships—as well as state policy—facilitate student employment.

Data come from remote video interviews conducted between May 2020 and November 2021 with 134 individuals working at or associated with sixteen different community colleges in California, Texas, and Ohio. These states were chosen because they cover a variety of industry, policy, and employment contexts and offer a wide range of settings and sizes of community colleges. One of the institutions, Texas State Technical College (TSTC), focuses nearly exclusively on workforce development education and, thanks to an innovative state policy, receives all of its public funding based on the earnings of its graduates. That makes it a valuable comparison point for the others, which focus simultaneously on workforce outcomes and four-year college transfer readiness. Interviewees included presidents, provosts, directors and staff of career services and student affairs, deans, faculty, navigators and counselors of workforce development education programs, employers, regional coordinators, and state policymakers.

It is important to note that no outcome data are included or analyzed as part of this report. While TSTC’s efficacy in training students for and placing them in jobs is key to its existence, none of the other institutions studied had such information readily available. Additionally, data on students’ use of services were very limited and thus are also not part of this report. As a result, any claims of “success” or “quality” are based almost entirely on inputs—state policy landscape, services offered, business partnerships created, and the like.

For example, the report states that “student use of career services appears generally to be low.” This is a negative, of course, but we have no numbers to analyze. Worse, the only clues in the report as to why this might be are that most schools do not heavily market their career services to students and that most schools opt for a centralized model of service provision that does not focus on supports for specific career fields. (More on that below.) But even if less-than-exemplary practices were to be improved at any of these schools, there is still no guarantee that students would take advantage of them.

Similarly, the researchers find that all three states have numerous policies and incentives in place to encourage a greater linkage between community colleges and the many industries for which they are increasingly training students, but none of the states have any actual requirements for schools to provide services or confirmation that any services were provided.

This is where the RAND report can be helpful. The interview subjects were quite willing to discuss the systems their institutions have put in place. The most common services provided include career exploration for students trying to home in on a field of interest, preparing students to search for and apply for jobs, and matching students with specific job openings. Service models generally took one of two forms: centralized, which means a single office/similar set of services for the entire school, or decentralized, which embeds some or all career services into separate and specific academic areas. The researchers considered the latter to be a stronger model, allowing services to be targeted to specific majors and career fields, especially when career exploration was made part of the academic track in the form of mandatory, graded courses.

In terms of workforce development offerings, work-based learning was widespread among the colleges, including practical, industry-related class projects; job-shadowing opportunities; and facilities and labs that mimic the workplace. However, apprenticeships—actual work in the field—were much less prevalent due to the stronger commitments required by both employers and career services staff to make these happen. In fact, most colleges in the study relied upon advisory committees for creating partnerships with local industry players. Unfortunately, committee members interviewed explained that the terms of membership and the infrequency of meetings limited most members’ ability to build partnerships in a meaningful way. A few colleges in the sample did stand out strongly in this area, structuring advisory committees to ensure employers’ continued involvement, establishing industry partnership offices in the community, partnering with other colleges, and sharing their institutional resources with employers to help build and maintain connections.

Once again, the researchers note a lack of clear and consistent measures for partnership accountability and performance assessment and little in the way of established infrastructure or protocols for data reporting, monitoring, and sharing. Added to all of these limitations is an expressed competition for resources and attention between career-focused majors and four-year-college transfer preparation, with the latter generally seen by interviewees as more favored.

The majority of recommendations emerging from this analysis involve more: more personnel, more industry partnerships, more internship opportunities, more technology, more outreach to students, etc. And it all boils down to more money. But first and foremost, data systems are needed to track who is coming through the office door, how they are served, and what outcomes are achieved.

SOURCE: Rita T. Karam, Charles A. Goldman, and Monica Rico, “Career Services and College-Employer Partnership Practices in Community Colleges,” RAND Corporation (June 2022).

Dozens of states and cities provide “college promise” programs. Intended to incentivize high school graduation and college matriculation, they typically offer to cover postsecondary tuition expenses. These programs are often touted as “free college,” though they typically fall short of full financial support and lead to underutilization and dropouts. A new qualitative study looks to describe how one such program is perceived and experienced by awardees in hopes of understanding how to best execute such programs in the future.

Data come from nineteen semi-structured focus group interviews conducted in March and April 2018 on the campuses of ten postsecondary institutions across Tennessee: three technical colleges, six community colleges, and one four-year college. Interviewees were first-year recipients of the Tennessee Promise scholarship and 60 students ultimately participated. Thirty-six were male, twenty-four female; forty-three were White, sixteen were Black, and one student was not identified by racial background. Discussions centered on students’ college decision-making process, expectations for and experiences in their first semester of college, and perceptions of resources and information available to them moving out of high school and into college.

Through several rounds of analysis and coding of responses, researcher Jenna W. Kramer constructed an overarching framework of relationships and actions that the average student identified as part of his or her pathway into college. The State of Tennessee was the key player, according to student interviews, beginning while they were in high school. Specifically, the eligibility criteria for Tennessee Promise scholarships include a community service requirement. This was identified by interviewees as the main hurdle put in place by the state to earning the scholarship. Requirements such as steady enrollment and minimum senior year GPA were seen as “no big deal” by most students, which makes sense, given that these are typical expectations of any high school student looking to earn a diploma. But those who pursued the opportunity and persevered largely believed that the state gave them tuition money in exchange for the community service work. Maintaining the award while in college required a minimum number of credit hours along with continued community service, commitments which many awardees said likely deterred some of their peers from applying.

Another key role was played by the non-profit entity tnAchieves, which manages disbursement of funds and provides mentorship and other supports for awardees. In fact, because students engaged with tnAchieves before they enrolled in college, they often came to see it as more important to their success than the colleges themselves. Interviewees described the organization performing roles more typical of college professors and advisors. Interestingly, both the nonprofit and the colleges were most frequently cited for their assistance in finding and maintaining community service work. That element clearly looms large for awardees.

With the state and tnAchieves filling the roles of financial and technical support—and with students motivating themselves to study, achieve, and complete service hours—parents and families mostly acted as moral support and cheerleaders. They also helped keep track of deadlines and paperwork completion.

In general, the structure of the Tennessee Promise program seemed well suited to its intentions. It motivated high schoolers to reach college—including many for whom a postsecondary academic track would not have been under consideration without the scholarship—and supported them once enrolled. That support mattered greatly to those without the social capital of college-going family and friends.

One place where the effort appeared to falter, however, was actual financial support. Tennessee Promise, being a “last-dollar” scholarship, covered tuition amounts remaining only after other federal and state funding sources were applied, and those, in turn, depend on family income. Thus the award amount varied greatly among students. Some received thousands of dollars from the program toward their tuition, others just a few hundred. But the community service requirement was the same for everyone. All students were responsible for their own textbooks and supplies—a particularly pricey list for those attending technical school—as well as living expenses. Students from the lowest-income families reported receiving cash refunds of any excess amount of their federal Pell Grants, which they could then use toward books and even food.

Awardees were generally aware of these disparities, and those who struggled to make up the gaps felt the state could have provided better information to them before the first bills came due. They also suggested a fairer means of subsidizing the additional costs, such as separate stipends earmarked for books and transportation, the latter an oft-cited deterrent toward success.

Kramer notes that all the interviewees were students in their second semester of college and thus had already successfully navigated numerous potential problems. The stories of awardees who were not able to maintain enrollment through the first semester would likely show more and different cracks in the framework. But those who did overcome problems and persevere at least this far can teach us a lot. She couches her analysis in terms of the “psychological contract” between students and the various players in the process, but in the end, it seems much simpler. The architects of this program understood much about what high school graduates need to make it to and through college and built a relatively sturdy base on which to deliver them.

SOURCE: Jenna W. Kramer, “Expectations of a Promise: The Psychological Contracts Between Students, the State, and Key Actors in a Tuition-Free College Environment,” AERA Journal (May 2022).