Ohio needs a knowledge movement to take the science of reading to the next level

Led by Governor DeWine, the science of reading is taking off in Ohio—and not a moment too soon.

Led by Governor DeWine, the science of reading is taking off in Ohio—and not a moment too soon.

Led by Governor DeWine, the science of reading is taking off in Ohio—and not a moment too soon. To date, the focus has been on essential skills, especially phonics, which systematically teach children letter-sound relationships to help them decode words. Such attention makes sense, given the critical role of phonics in building the foundation for reading.

But the science of reading is more than just phonics. The influential National Reading Panel report identified five pillars that together constitute what’s known as reading science: phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension. All five elements are necessary. As the National Council for Teacher Quality wrote in our recent report, “all the components, working together, are essential to developing strong readers.”

In the realm of comprehension, students need a wealth of background knowledge to make sense of what they’re reading. This notion, based on the influential work of E.D. Hirsch, Jr., makes intuitive sense. It’s easier to comprehend material on topics we’re familiar with, while we often struggle with texts outside of our experience. Cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham writes, “Three factors are important in reading comprehension: monitoring your comprehension, relating the sentences to one another, and relating the sentences to things you already know.” The upshot is that the wider and deeper a child’s knowledge base, the better reader he or she will be.

One example: A child proficient in phonics can sound out the word “walrus.” But only a child with an understanding of sea animals will know what that is.

How can elementary schools build a strong knowledge base? Best is to adopt a literacy curriculum that intentionally builds students’ knowledge. A stellar example is Core Knowledge Language Arts (CKLA), a comprehensive K–8 curriculum that includes language arts, math, history, geography, science, and the arts. Created more than two decades ago by Hirsch and his colleagues, CKLA is already used in some 1,700 U.S. public schools. While there’s no hard data on its use in Ohio, recent news reports indicate growing interest in this curriculum among school leaders. Several classical charter schools in Ohio have adopted CKLA, as have the United Preparatory Academics, two high-performing elementary charters in Columbus.

A recent study published by Brown University suggests that more Ohio schools should consider moving to CKLA. In it, the analysts track the outcomes of students attending one of nine Colorado charter schools that implement Core Knowledge. Though small-scale, the researchers provide strong causal evidence about the effect of attending these schools by leveraging Kindergarten lottery admissions data. This helps to approximate a “gold standard” experiment, as children are randomly assigned to treatment and control groups. The study includes 2,360 school applicants, of whom 35 percent won the lottery (and about half of those students enrolled in the charter schools). The researchers then analyzed state test results of lottery winners and losers from grades three through six to gauge the academic effects of attending a CKLA school.

The results are impressive. Lottery winners who attend CKLA schools post reading scores that are significantly higher than their peers who did not get a winning ticket. The impacts are substantial, too, equivalent to gaining 16 percentile points on state reading exams. The positive effects show up starting in third grade, the first year of test data, and persist through sixth grade. The results in math are also positive, though not statistically significant.

Of the nine CKLA charter schools in the analysis, eight were located in mid- to higher-income communities. One was in a low-income area. In that school, the results are even more pronounced. The academic gains for students attending it are “very large” in both reading and math, significantly higher than those registered in the other eight CKLA schools. The researchers note that, for this school, the “effects were large enough to close achievement gaps for disadvantaged students by third to sixth grade in all subjects measured.”

Commenting on the study, my Fordham colleague Robert Pondiscio—a longtime evangelist for background knowledge—writes, “If we want every child to be literate and to participate fully in American life, we must ensure all have access to the broad body of knowledge that the literate take for granted.”

There is great truth to that statement. Achieving this goal starts with decisions that school leaders make today about which reading curriculum they’ll use in their classrooms. Will it be one that skimps on knowledge building—often focusing on ineffective “comprehension skills” instead—or is it one that intentionally builds children’s knowledge about the world around them?

Core Knowledge isn’t the only great option. Wit and Wisdom and EL Education are two other excellent curricula. Given their remarkable benefits for low-income students, Ohio’s urban districts, where literacy rates are lowest, should take an extra close look at such curricula. Charter schools can help fuel the movement, too. Colorado, for example, is currently home to fifty CKLA charters.

The science of reading promises to help thousands more Ohio students become strong, lifelong readers. A return to phonics is a necessary start, and kudos to Governor DeWine and early-adopting schools across the state for focusing on this foundational skill. But that’s just the start. Ohio’s literacy efforts can build to an even higher level of success by making knowledge-building the next frontier.

In 2021, during the previous state budget cycle, lawmakers used federal pandemic relief funds to create the Afterschool Child Enrichment (ACE) educational savings account. The program, as initially designed, provided families whose income fell below 300 percent of the federal poverty line with $500 a year per student to pay for enrichment activities chosen by parents, regardless of where their children attended school. Examples of such activities included before- or after-school educational programs, day camps, field trips, language or music classes, and tutoring.

It might seem surprising that the state was willing to pay for activities happening outside the walls of a school building. But doing so was a smart move, as there’s a growing body of research indicating the positive impact of extracurricular and enrichment activities for kids. One study even found that consistent participation in extracurricular activities between eighth and twelfth grade predicted academic achievement and prosocial behaviors. Unfortunately, research also indicates that participation in such activities is less common among students from lower-income families, largely due to the cost of participating and a dearth of opportunities. The pandemic made things worse: Providers closed, low-income families had less to spend, and the enrichment gap widened.

ACE was created at a time when Ohio families were still reeling from the impacts of the pandemic. As a result, the program had the potential to be hugely beneficial and popular. Families struggling to make ends meet would be able to ensure their kids had access to the same extracurricular opportunities as their more affluent peers. And ACE accounts as a whole could reduce at least some of the disparities between lower- and higher-income students statewide.

That’s not what happened (at least, not at first). Within a year of their creation, most Ohio families had no idea that ACE accounts even existed, let alone that they were potentially eligible for money. Coverage of the program in June 2022 in Gongwer Ohio noted that although $50 million had been allocated to support the program during its first year, only $106,749 in claims had been approved for just over 6,000 families. One state official at the Ohio Department of Education acknowledged that the program was “well below capacity” both in terms of participating families and providers, and that the department was “working on developing a package of marketing materials and social media content” to increase awareness and participation.

Legislation signed by the governor in early 2023 extended the ACE program through 2024 and increased the amount that families could be awarded from $500 to $1,000 per child. It also expanded eligibility to encompass families whose income is at or below 400 percent of the federal poverty level, those who participate in income-based programs like Medicaid and SNAP, and those who live in districts that include EdChoice-eligible schools or have been identified as experiencing high rates of chronic absenteeism (ODE provided a full list of eligible districts).

These were welcome adjustments that provided more Ohio parents with extra dollars to support their children’s needs. For a family with two children, the ACE funding is not a trivial amount ($2,000) and could cover a large range of enrichment activities. For families with more kids, the supplemental supports grow larger.

But the extra dollars and increased eligibility wouldn’t mean much if parents remained uninformed. Fortunately for Ohio families, ODE stepped up to the plate and hit parental outreach out of the park. Details about the program, including the increased dollar amount available per student and expanded eligibility rules, were published in newspapers in major cities all over the state, including Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Canton, and Toledo. Local television stations ran detailed stories about ACE during news programming. Online news sources covered the program. Ads appeared on the websites of organizations offering enrichment activities, like the Akron Fossils and Science Center. And there was social media outreach, too. For example, a writer for The Land, a nonprofit news organization focused on Cleveland, wrote about how she saw an ad for the program on Facebook. The best part? Most of the informational onslaught was done in early April, giving families plenty of time to apply for funds and choose a provider before summer hit, which is when enrichment opportunities are particularly vital.

Alas, additional funding for ACE accounts wasn’t included in this year’s budget. That’s likely because the original program was funded via federal dollars, which have since dried up. Barring an unexpected last-minute addition, the 2023–24 school year could be the last for Ohio parents to use state-provided funds to pay for enrichment activities. Now that ODE has done such excellent work spreading the good news, though, lawmakers should pay close attention to participation rates this summer and next year. If a huge influx of parents takes advantage of the program, that could be a sign that lawmakers should consider using state funds to extend ACE accounts.

For several years, thousands of charter, private, independent STEM, and district students across the state have suffered at the hands of a broken transportation system. Blame for the trouble has been laid at the feet of mediocre pay for drivers, burgeoning school choice, software and logistical woes, and insufficient funding.

The Ohio Department of Education and the General Assembly have been trying to solve the issue with legal mandates and fines. These are an appropriate first response, as they ensure that school districts—which are currently responsible for almost all student transportation—understand that the state is serious about making sure kids get to school safely, reliably, and on time. Unfortunately, districts have responded by tying those sanctions up in litigation that might just get resolved before the youngest students who are currently transportation-eligible reach high school. In the meantime, the wrecked system continues apace, while districts demand fewer service requirements and/or giant cash infusions from the state.

Kudos, then, to Ohio lawmakers who are offering some creative proposals to tackle the state’s transportation woes. Yes, the state budget bill does propose significantly increasing funding for student transportation, but it also contains numerous measures to make systems more modern, nimbler, and more responsive to the students and families who depend on them. Here are a few of those important proposals, which can be found in the current iteration of the state budget bill:

There are several more transportation proposals in the bill as it stands right now, both large and small, for which our legislators are to be commended. If all of them are enacted, families across Ohio should quickly see an enormous improvement in the availability, flexibility, and reliability of transportation services.

On May 9, the Cleveland Metropolitan School District (CMSD) announced that it had hired Dr. Warren Morgan as the district’s new CEO. Morgan will replace Eric Gordon, who has been at the district’s helm since 2011.

CMSD deserves plenty of kudos for involving a variety of stakeholders at several points throughout the hiring process. Such efforts include conducting a stakeholder survey aimed at identifying the primary priorities and concerns of the district’s families, students, and staff, as well as convening panels of students and parents to interview finalists.

Morgan will officially take over on July 24. The new CEO already has the support of the city's young mayor and an updated Cleveland Plan on the books, both of which are good news. But he’s also stepping into a district with persistently low student achievement and growth along with myriad other issues—many of which were highlighted by families and community members during the hiring process. Based on this stakeholder feedback, here’s a look at four things that Morgan should prioritize from day one.

1. Improving academic outcomes

The pandemic hit CMSD particularly hard. In fact, learning losses in Cleveland exceed those in many other cities. Up on the shores of Lake Erie, though, the urgent need for academic improvement is about more than just pandemic recovery. CMSD has a long history of troublingly low student achievement. That’s why the Cleveland Plan exists in the first place. It’s no surprise, then, that survey results identified improving the quality of the district’s academic programs as a top priority. Concerns about achievement disparities based on race also “loomed large” in survey results, and community members expressed interest in identifying the “resources and opportunities” students need to succeed.

Morgan has several options in that regard. One would be to double-down on the district’s commitment to high-dosage tutoring (HDT), which research shows can produce large learning gains for students. Thanks to federal Covid relief funds and a state grant program, CMSD has already partnered with several local colleges and universities to offer HDT to small groups of students. But there are thousands more who could benefit from additional offerings. The Ohio Department of Education has already done the work to create a list of high-quality tutoring providers and programs. If district leaders haven’t done so already, Morgan could contract with one (or several) of these providers and offer HDT to every CMSD student who scores at the lowest level on spring state assessments, or within the district’s lowest performing schools.

Another option would be to capitalize on the district’s existing summer school program (though Morgan would obviously need to wait until next summer to do so, as it’s far too late to overhaul this year’s program in any meaningful way). Over the last several years, CMSD has implemented a Summer Learning Experience that offers K–8 students systematic instruction in literacy and math during the morning, a variety of enrichment activities, and summer camp–like experiences in the afternoon. High schoolers, meanwhile, can sign up for credit recovery courses and enrichment activities geared toward older students.

The program has proved to be popular—nearly 7,000 students signed up last year—but there are still tens of thousands of students who would benefit immensely but aren’t attending. Morgan could make it his mission to bolster sign-up numbers, as well as daily attendance, and might even consider requiring any student who scored at the lowest level on spring state assessments to participate. It’s also unclear how rigorous the academic portion of the experience is, especially for high schoolers. Morgan could focus his efforts on ensuring that all students are provided with the evidence-based instruction and intervention they need to catch up.

2. Ensuring access to high-quality curricula

Ensuring that every student in Cleveland has equitable access to high-quality curricula and additional learning opportunities should be a priority for Morgan. In the district’s stakeholder survey, parents and community members expressed concerns that “resources were not fairly balanced between school buildings” and that higher-performing schools offered “more opportunities” for students. Survey results also indicate that increasing access to career and technical education (CTE) is a priority.

State leaders are poised to ratchet up their commitment to and investment in CTE, so Morgan could soon have increased state funding and support to address that particular concern. But his biggest opportunity will be in early literacy, as state leaders are aiming to revamp how Ohio schools teach reading by requiring them to use high-quality curricula and materials aligned to the science of reading. Right now, several CMSD elementary schools use curricula that aren’t grounded in reading science. In fact, the district’s K–3 Literacy Framework identifies several problematic curricula and materials, such as Fountas & Pinnell and Units of Study, as “recommended resources.” These programs call on teachers to use debunked instructional methods like three-cueing, which encourages students to guess at words rather than actually read them, even though the research is clear that it’s an ineffective way to teach kids how to read.

To address this, Morgan and his staff could establish a high-quality, district-wide curriculum that’s firmly rooted in the science of reading. However, doing so would run counter to CMSD’s commitment to empowering principals to make decisions—a commitment that’s at least partially responsible for upticks in student growth prior to the pandemic. A compromise would be to allow schools to opt out of the district’s chosen curriculum as long as they select high-quality, scientifically-based options instead. Curricula and materials that don’t align with the science of reading should be prohibited.

3. Improving security and school safety

Based on survey results, improving safety both inside and outside of district buildings is the number one concern of parents. Even a quick perusal of local headlines shows why they’re concerned. Several teenagers were shot and killed near school buildings during the 2022–23 school year, including a CMSD student who was waiting for a bus after school.

Morgan told the stakeholder panel that he had experience with school safety issues during his time as a principal in Chicago. As a former teacher, I can vouch that his experience as both a teacher and administrator in big cities like Cleveland—he was a secondary science teacher in St. Louis—is important. It’s difficult to replicate the firsthand experience of working daily in a classroom and school building and understanding the ins and outs of what it takes to keep students safe. Morgan also told the panel that, should he be hired by the district, he would do a “safety audit” of buildings and walk students’ routes to school, presumably to pinpoint areas for concern that need to be addressed.

These ideas are a good start. Morgan will likely find that seeking out the opinions of students and families, as well as teachers and administrators, will bring more good ideas to the fore. In fact, he’s already indicated that he’s open to doing so, having mentioned working with a student advisory group in Chicago and taking their concerns to the city’s mayor and police chief. What will truly matter, though, is what Morgan does with those ideas. Paying lip service to school safety and security is one thing—politicians do it all the time—but actually addressing safety and security issues in an effective and fair manner is another.

It’s also worth noting that, aside from the obvious importance of keeping children safe and ensuring that they feel secure enough to learn, addressing safety issues could improve other weak spots in the district, as well. For example, it’s possible that security concerns are driving some of the attendance issues the district is facing, and addressing truancy was one of the priorities highlighted by the stakeholder survey. Cleveland’s student attendance issues predate the pandemic, and it goes without saying that school closures and Covid have played an outsized role in kids’ likelihood of missing school. But safety matters, too. If students—and their parents—don’t feel safe traveling to school or being in district buildings, then they might be less likely to attend.

4. Maintaining what’s worked

In an analysis of a 2021 study which found that Cleveland was making gains on NAEP, I identified three critical areas that could explain the district’s improvement. Two of the three are areas that Morgan should continue to prioritize.

First is school choice, which the stakeholder survey identified as a “positive” that community members wanted their new CEO to embrace. CMSD is unique in Ohio because it’s a portfolio district. Families use the district’s school choice portal to select a school for their child rather than being required to enroll at the closest building. They can choose up to five schools, ranking them in order of preference. Charter schools have also contributed to the city’s success. Research shows that a higher charter market share in urban areas is associated with significant achievement gains for Black and Hispanic students, and that the existence of charters doesn’t have a negative effect on district schools. That’s playing out in Cleveland, where CMSD sponsors nine charters and has partnered with an additional eight. Cleveland is also home to Breakthrough Public Schools, one of Ohio’s best charter networks.

Second is transparency and accountability. Each year, the Cleveland Transformation Alliance (CTA), a nonprofit responsible for supporting implementation of the Cleveland Plan, releases a report that measures the district’s progress against a broad set of goals. The CTA website is also home to a school finder that allows parents to examine data profiles on each school and compare several schools at once. This information is crucial for families. It also demonstrates the district’s commitment to being transparent about results, and empowers stakeholders and advocates to hold the district accountable for a variety of metrics.

***

All things considered, CMSD staff and families should feel hopeful about their new CEO. Morgan has a history with the district, as he worked for CMSD during early implementation of the Cleveland Plan. His most recent hiring was the result of a comprehensive process that actively sought out stakeholder feedback. And his experience in other large, midwestern districts aligns with Cleveland and its most significant needs—improving student outcomes in the wake of the pandemic, upgrading curricula and ensuring equitable access, and addressing urgent student safety needs. If Morgan can prioritize these critical areas while also maintaining the things CMSD already did well—like championing school choice and being transparent with the community—then the district has nowhere to go but up.

NOTE: This morning, the Ohio Senate Finance Committee heard testimony on Substitute House Bill 33, the state’s budget bill for fiscal years 2024 and 2025. Fordham’s Ohio Research Director provided this written testimony on important provisions of the bill as amended in committee.

My name is Aaron Churchill, and I am the Ohio Research Director at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. The Fordham Institute is an education-focused nonprofit that conducts research, analysis, and policy advocacy with offices in Columbus, Dayton, and Washington, D.C. Our Dayton office, through the affiliated Thomas B. Fordham Foundation, is also a community (charter) school sponsor. Thank you for the opportunity to provide written testimony on Substitute House Bill 33, the state’s biennial budget bill for fiscal years 2024 and 2025.

In this year’s budget bill, Governor DeWine and House lawmakers have made K–12 education a top priority. We’re pleased to see that the Senate has also done so. Taken together, the proposals in the budget will put more students on pathways to success in career, citizenship, and in life.

Let me first highlight several key policy reforms that are included in the Senate’s version of the budget and which Fordham strongly supports.

*****

Public charter schools: Equitable funding and accountability

Last, I’d like to touch on matters of charter school funding and accountability.

On the funding side, Ohio has historically left charter schools under-resourced, providing them with approximately 30 percent less per-pupil compared to local districts. Such a wide gap puts charter schools—and the students they serve—at a significant disadvantage. Without equitable funding, charters often struggle to provide extra supports and enrichment opportunities. They also face challenges in attracting and retaining talented teachers, as they’re left paying less competitive wages. Finally, the gap limits charters’ ability to expand and reach more Ohio students in need of a great education.

We at Fordham enthusiastically support the significant boost in funding for the Quality Community Schools program that the governor proposed and the House and Senate included in their budgets. In fact, the additional dollars will be a game changer for the one-third of charters that receive these funds, helping them expand and reach more students in need of a great education.

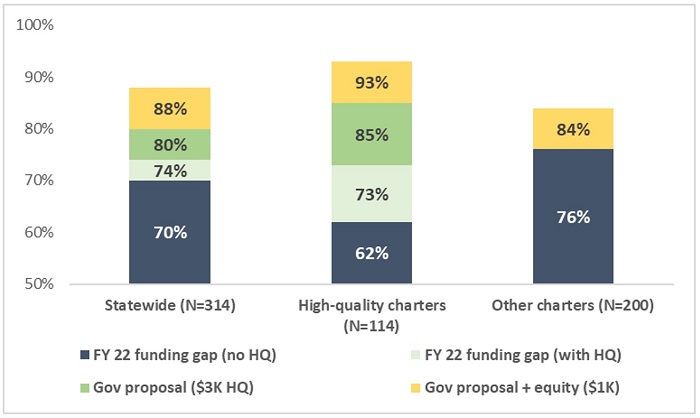

But even with this proposed increase, the average high-quality charter school would still fall well short of funding parity with local districts. Other brick-and-mortar charters would continue to face daunting funding gaps, as they receive no supplemental dollars at all. Many of these schools serve large numbers of low-income and special-education students; some focus on serving adolescents who have dropped out. To provide fairer funding for charter students, we ask you to support a $1,000 per pupil equity supplement for all brick-and-mortar charters, in addition to the increase for the high-quality charter fund. As Figure 1 below indicates, an equity supplement would bring charters overall to an average of 88 percent of the per-pupil funding of local districts. This more modest shortfall would track closely with the funding differentials in states with strong charter sectors such as Massachusetts and Texas.[2]

Figure 1: Impact of a charter school equity supplement[3]

As we ask you to spend additional dollars to bridge the funding gap, we also insist on strong accountability for results. One critical element of Ohio’s charter accountability framework is its sponsor evaluation system, which holds sponsors accountable for the performance of the schools they oversee. This system ensures that these entities, which allow charters to open and continue to operate, are focused on quality. It also encourages them to move quickly to close schools that are underperforming, and rigorously vet prospective startups. Strong measures at a sponsor level are likely a reason behind the steps forward in overall charter sector performance in recent years.[4] Paired with equitable funding, these rigorous charter accountability mechanisms will drive further improvements in the years ahead.

Parental empowerment, accountable school systems, strong literacy policies, and equitable and efficient funding can only help to increase student achievement. This budget bill focuses on these issues and it holds great promise for Ohio students and families.

Thank you again for the opportunity to submit written testimony.

[1] For a review of the Ohio study and those from other states, see: https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/commentary/more-evidence-time-ohio-third-grade-retention-works.

[3] More detail about these calculations is at: https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/commentary/ohio-narrowing-charter-funding-gap-it-still-needs-do-more.

[4] More about sponsors and charter accountability is at: https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/reinventing-ohios-charter-school-sector-2015-2023-ohios-successful-charter-turnaround.

This spring, the national education nonprofit EdChoice published a “capstone” report outlining a series of research projects it conducted alongside Hanover Research. The report focuses on open enrollment, a school choice model that allows students to attend public schools other than the one they’re assigned to by their district of residence. As implied by the “capstone” designation, the report offers a sweeping look at open enrollment across the nation, including literature reviews of participation and impacts, detailed case studies of four states (Arizona, Florida, Indiana, and Ohio), and several policy implications.

The report’s introduction offers some important context. It notes that, over the last few decades, public education has experienced a gradual shift away from assigned public schools and toward allowing parents to actively choose a school for their child. This shift has been hastened by “multiple forces,” including growing participation, public support, and innovation in school choice programs. The pandemic also played a part, as it left many parents dissatisfied with their assigned schools and searching for other options. Among the choice options available in most states are charters, magnet schools, virtual schools—and open enrollment.

There are two forms of open enrollment: intra-district, which allows students to transfer from one school to another within their resident district; and inter-district, which allows students to attend a school in a district other than the one in which they live. The first ever statewide open enrollment bill was passed in Minnesota in 1988, and forty-three states now have similar laws. A whopping 86 percent of the nation’s public school students now live in states with inter-district choice programs, and 41 percent live in states where offering open enrollment is mandatory (at least in some cases). Meanwhile, twenty-one states require districts to offer intra-district choice, and seven others have laws that allow districts to choose to participate. At the local level, an increasing number of large urban districts are eliminating attendance zones in favor of intra-district choice programs characterized by unified enrollment systems and a common application for families. And although nailing down participation numbers is tricky, the report suggests that the percentage of public school students participating in inter- or intra-district choice programs could be as high as 3.5 million students, or 7 percent—on par with the number in charter schools.

As for impacts, the report notes that different studies draw different conclusions. This is not surprising, given that policies are distinctive from state to state and district to district. Nevertheless, the report identifies several important conclusions. First, most parents cite school quality as their primary reason for choosing open enrollment, followed closely by school safety and environment, and then proximity to work, home, and daycare. Second, there is a tendency for students from poorly resourced, low-performing schools to transfer to well-resourced, high-performing schools. For example, a 2015 Michigan study found that historically disadvantaged students were most likely to request inter-district transfers, and an analysis from Wisconsin found that low-income districts experienced the highest rates of outmigration. Third, some studies identified evidence of higher academic achievement (Fordham’s 2017 study of Ohio’s program certainly did), while others found achievement to be unchanged or lower. Fourth, students and parents tend to express high rates of satisfaction with their new schools, though parents seem less than thrilled when it comes to transportation (more on this later). Finally, although some studies find that open enrollment policies can result in “greater stratification” by socioeconomic status and race, others find that open enrollment can actually increase diversity in receiving districts. (In Ohio, a 2021 Fordham study found that inter-district open enrollment had virtually no effect on segregation across districts or at the school level.)

The report also offers a more in-depth look at the inter-district open enrollment policies in four states—Arizona, Florida, Indiana, and Ohio. Although each case study is worth a read in its own right, here are a few overarching takeaways.

1.) Arizona and Florida have the least restrictive open enrollment policies. Both states require all public districts to adopt inter- and intra-district policies, which result in widespread school choice options for families. In Florida, districts and charter schools must develop and adopt an open enrollment plan, and they must also define their capacity and clearly post it on their websites.

2.) Indiana and Ohio have more restrictive open enrollment environments for students because districts may opt-out of inter-district open enrollment. Although districts in Indiana and Ohio get to choose whether to accept non-resident students, both states outline certain instances when a district is required to allow inter-district open enrollment. Indianapolis Public Schools, for example, is required to accept both inter- and intra-district transfers.

3.) Transportation is a huge barrier. In all four states, parents and guardians are largely responsible for getting their kids to their chosen school. Unsurprisingly, this can cause a lot of headaches for families.

4.) Although open enrollment can cause equity and access issues, states with voluntary inter-district policies struggle most. In Ohio, most of the affluent and suburban districts that surround the state’s eight major cities refuse to participate in open enrollment. As a result, “public perception generally perceives these suburban districts to be intentionally preventing students from nearby urban centers from enrolling” and therefore “barring access to high-quality education.” Meanwhile, in Indiana, districts were previously allowed to accept or deny students based on criteria like academic achievement, discipline records, and test scores. When a 2013 law prohibited them from continuing to do so, many districts opted to just stop accepting open enrollment transfers.

To accompany this literature review, Hanover conducted in-depth interviews with several district administrators. According to interviewees, open enrollment has positively impacted families and students alike. They reported feeling competitive pressure and often referenced the need to “retain market share” by attracting students from nearby counties. They also noted that many schools have created new or improved existing programs in an effort to retain students, and that districts are consistently using marketing and communication strategies to reach families outside their traditional boundaries. Every interviewee mentioned that open enrollment can make maintaining a “cohesive district system” difficult, not just because these policies can challenge community ties or change neighborhood school identities, but also because fluctuations in demand require constantly managing resources and capacity.

To close, the report covers several policy implications. At the state level, there are five. First, all inter- and intra-district choice programs should be mandatory for school districts. Second, state leaders should consider addressing transportation barriers within policy frameworks, perhaps by reimbursing parents for transporting their children or establishing conveniently located satellite bus stops. Third, open enrollment should be offered to all students, without them needing to meet certain criteria. Fourth, funding flexibility is crucial, as many state funding formulas aren’t designed to permit students to transfer between districts without creating financial disincentives. And finally, if state leaders opt to include capacity provisions, then parents must be able to easily find which schools have open seats. Arizona, Florida, and Oklahoma all require districts to post their open seats by school, grade level, and program, and to update those numbers periodically.

Implications were also included for districts (administrators must remember that transportation can be highly influential, and that school culture and academic programming matter to students), researchers (we need to better understand the potential connection between open enrollment and student achievement), and advocates (identifying and promoting solutions for transportation woes would be huge).

All things considered, it’s clear that open enrollment is a great option for millions of American families. Access to that option, however, largely depends on where a family lives and what school they want to send their child to. There are steps that policymakers, district leaders, and advocates can take to make open enrollment more accessible to more families. But report author Susan Pendergrass says it best: “Equality of opportunity comes not from trying to level the playing field between bureaucratic institutions, but from circumventing the institutions and empowering those whom they serve.”

Source: Susan Pendergrass, “Breaking Down Public School District Lines: Policies, Perceptions, and Implications of Inter-District Open Enrollment,” EdChoice (March 2023).