A closer look at early literacy results on state report cards

A few weeks ago, Ohio released state report cards for the 2021–22 school year.

A few weeks ago, Ohio released state report cards for the 2021–22 school year.

A few weeks ago, Ohio released state report cards for the 2021–22 school year. Annual report cards have been the law of the land for decades, so Ohioans are generally familiar with them. But report cards themselves look a little different this year, as the state legislature revamped the framework during summer 2021.

Although the biggest change was a shift from an A–F to a five-star system, several individual components also got a facelift. That includes the early-literacy component, which measures reading improvement and proficiency for students in grades K–3. To provide a more complete picture of early literacy in Ohio schools, the component now includes three measures, the first two of which were added via last year’s reform legislation.

1. Proficiency in third grade reading

This measure reports the number of students who score proficient or higher on the reading segment of the third grade English language arts (ELA) state test. This is not the same as overall proficiency rate on the ELA test, as this measure covers only the reading segment of the test and excludes the writing part.

2. Promotion to fourth grade

This measure reports the percentage of students in third grade who were promoted to fourth grade, and thus were not subject to retention under Ohio’s Third Grade Reading Guarantee.

3. Improving K–3 literacy

This measure uses two consecutive years’ worth of data to determine how well schools and districts are helping struggling readers. It uses the results of fall diagnostic assessments and the state test to determine the percentage of students who moved from not on track in reading to on track from one year to the next.

Although these three measures are unrated, the state combines them to create an overall early-literacy rating for districts and schools. That rating is calculated by adding up the results of all three measures—which are weighted according to state law—to establish a weighted early-literacy percentage. This number is then compared to score ranges set by the state board of education to determine a school’s rating. As is the case with other report card components, schools receive ratings of one to five stars.

So how did Ohio districts fare in the wake of pandemic-related disruptions? Well, the good news is that, of the state’s 607 districts, 397 of them—roughly 65 percent—met or exceeded state standards and earned early-literacy ratings of three, four, or five stars. That’s great news for Ohio kids, and falls in line with analyses by Ohio State’s Vladimir Kogan, who found that ELA achievement among third graders has “charted an impressive rebound” after plunging earlier in the pandemic.

On the bad news front, 208 districts earned either one or two stars. That means approximately 34 percent, or one third, fell into the “needs support” or “needs significant support” categories. All three of the districts that recently emerged from state oversight via an Academic Distress Commission (ADC)—Youngstown, Lorain, and East Cleveland—earned only one star. And all but one of the Big Eight districts also earned only one star (Cincinnati earned two).

Taken together, the Big Eight and former ADC districts serve nearly 154,000 students. And while most of their students are older than grades K–3, many of them learned to read in the same elementary schools that are earning troublingly low early-literacy ratings. Obviously, the pandemic played a part in declining scores, but many of these districts were struggling with early literacy long before then. It’s also important to remember that, while helpful, districtwide ratings can mask low scores for individual schools. Even in districts that scored well, there could still be schools full of students who are struggling to read.

If state and local leaders don’t take these results to heart, thousands of students will pay the price down the road. Fortunately, Ohio seems to be headed in the right direction. The Ohio Department of Education’s recently released budget priorities aim to boost early literacy in some smart ways, including incentivizing the use of high-quality instructional materials, encouraging professional development for teachers in the science of reading, and deploying literacy coaches to low-performing schools. And so far, state leaders have resisted political pressure to eliminate the Third Grade Reading Guarantee’s retention requirement, which is backed by strong evidence.

There are other interventions—like doubling down on the potential of out-of-school time or increasing the support that persistently low-performing schools receive—that are also worth investment. But going into budget season, it certainly seems like Ohio leaders are focused on improving early literacy. Given just how many districts had abysmal early-literacy scores, that’s clearly the right approach.

The past two school years have been anything but normal due to pandemic disruptions, with student achievement showing the strain. State testing results from 2020–21 released last September revealed that Ohio students had lost approximately one-third to a full year of learning relative to pre-pandemic cohorts. Those data, however, were not a complete “census” of achievement, as larger-than-usual numbers of students were untested. Those data also couldn’t yet capture any bounce-back from schools’ academic recovery efforts.

Now with state assessment results from 2021–22 in hand, we’re getting a clearer sense of where students stand academically as we enter a post-pandemic era. In an important analysis, Professor Vlad Kogan of Ohio State University has already examined whether achievement in Ohio rebounded from the dips seen in 2020–21. He finds some bounce-back in reading but—dishearteningly—almost no recovery in math. Allow me to offer another accounting of the academic toll of the pandemic, and its especially severe impacts on disadvantaged pupils.

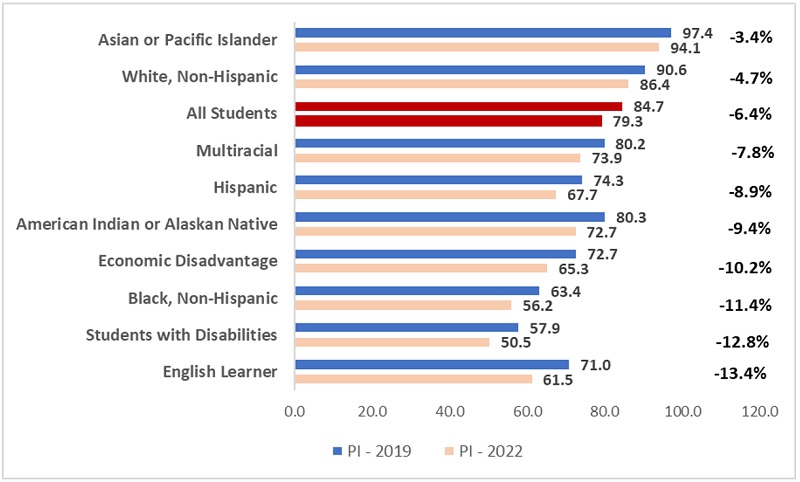

We begin with the big picture. Figure 1 displays the statewide performance index (PI) score for all students taking state exams, along with a breakdown of scores by the various student groups defined in federal and state law. The learning losses are clear. The overall statewide PI score fell from 84.7 to 79.3 from 2018–19 (the last pre-pandemic year) to 2021–22, a 6.4 percent slide. All the more striking is the large, double-digit declines among economically disadvantaged students, Black students, students with disabilities, and English learners—losses that widened the massive achievement gaps that existed before the pandemic. For instance, as measured by PI scores, Ohio’s Black-White achievement gap was 27.2 points in 2018–19. Now that gap is 30.2 points.

Figure 1: Ohio’s performance index scores, overall and by student group, 2018–19 and 2021–22

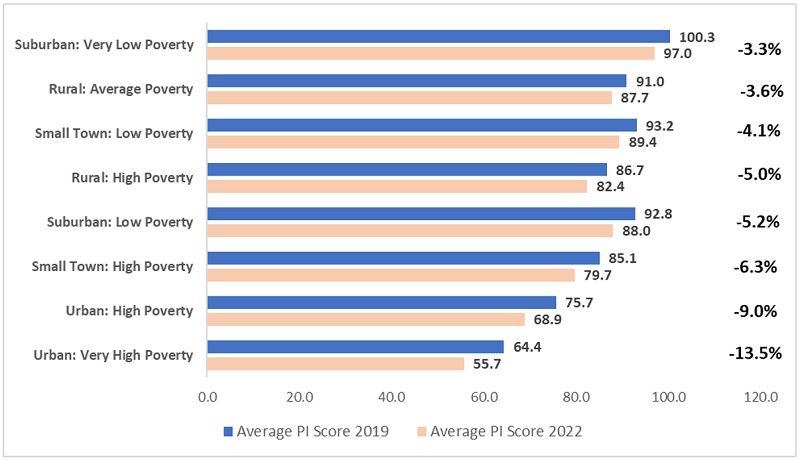

The next chart displays results by typology, a way of grouping schools by their geographic and socio-economic characteristics. Again, the learning losses are stark, but we see more pronounced impacts on students living in Ohio’s urban areas, where more low-income, Black, and Hispanic students reside. The average PI score in the “urban: high poverty” category fell by 9 percent. (This group encompasses inner-ring districts like South-Western and East Cleveland, along with smaller cities such as Lima and Mansfield.) Meanwhile, the largest declines in PI scores are visible in the Ohio Big Eight cities—i.e., the “urban: very high poverty” typology—where achievement fell by a staggering 13.6 percent. (The Big Eight are listed below in figure 4.)

Figure 2: Average performance index scores by typology, 2018–19 and 2021–22

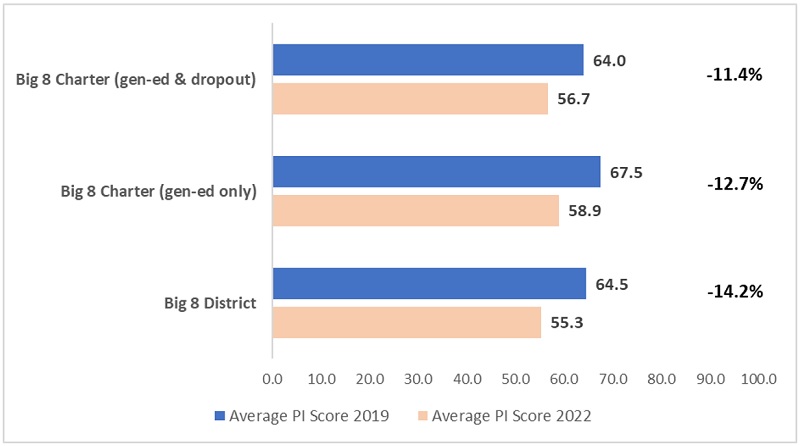

The next two figures focus on the Big Eight. Three in four Ohio charter schools are located in these cities, so we disaggregate the results by sector. Figure 3 indicates that PI scores are broadly similar both pre- and post-pandemic, with a slight edge to charters when one looks only at general-education charters in these cities. Pandemic learning losses are enormous in both sectors—steeper than the statewide average—so no one in these cities can really celebrate. Nevertheless, the Big Eight charter average—including both general-education and dropout-recovery schools—declined less than the Big Eight district average during this period (-11.4 versus -14.2 percent). Within the charter sector, losses were slightly larger in its general-education schools (-12.7 percent), with the less severe overall charter decline reflecting a slight gain in average PI scores for dropout-recovery schools located in these cities.

Figure 3: PI scores for the Big Eight cities, district and charter, 2018–19 and 2021–22

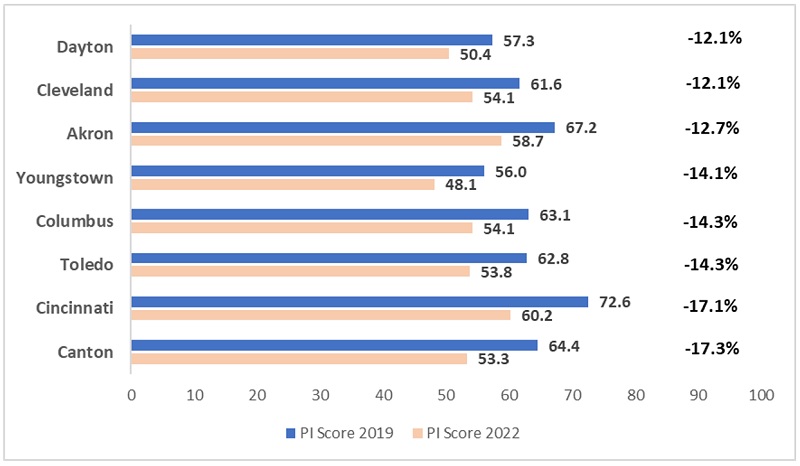

Last, figure 4 focuses on the Big Eight district results. Here, we see some variation in the extent of students’ learning losses. Canton and Cincinnati school districts lost more ground on the PI measure (-17 percent), while Cleveland and Dayton suffered relatively smaller losses during the pandemic (-12 percent). Nevertheless, Cincinnati still outperforms the other districts post-pandemic.

Figure 4: PI scores across the Ohio Big Eight districts, 2018-19 and 2021-22

* * *

The data are clear: Ohio students lost significant ground in math and reading during the pandemic, with disadvantaged students paying the heftiest price. Now the question is whether schools will turbocharge student learning—above and beyond the normal pace—so that the Covid-generation of students doesn’t leave high school ill-prepared. Can Ohio get students back on track? It’s a tall order, but tens of thousands of Ohio students are relying on their schools for the knowledge and skills needed for success in life.

Since 2015, College Credit Plus (CCP) has offered academically eligible Ohio students in grades 7–12 the opportunity to earn postsecondary credit by taking college courses for free before graduating from high school. State law mandates the participation of all public schools and public colleges and universities, but dozens of private schools and private higher education institutions across the state also participate.

CCP is a state-run, state-funded program that is jointly managed by the Ohio Department of Education (ODE) and the Ohio Department of Higher Education (ODHE). As such, it is subject to audit by the Ohio Auditor of State, and a performance audit was conducted in 2021. The recently published audit is worth a read in its entirety, as it offers an in-depth look at the program and proposes ten recommendations to improve participation and performance. But for those interested in a bird’s-eye view, here’s a look at the good, the bad, and the ugly.

The good: Overall participation, student impacts, and tuition savings are positive

CCP was established to address low student participation in Ohio’s original dual-enrollment program, the Postsecondary Enrollment Options Program (PSEOP), and so far, it’s done exactly that. The number of students participating in CCP, as well as the number of credits that have been attempted and earned, has grown every academic year with the exception of 2020–21, during the pandemic. Even then, over 76,000 students participated and earned roughly 650,000 credit hours. Compared to the final year of PSEOP (2014–15), when students earned approximately 190,000 credit hours, that’s an increase of roughly 240 percent. The majority of CCP participants (91 percent) were in high school, and nearly 70 percent of all courses were taken through a community college. Ohio now has one of the highest rates of dual enrollment in the country, and approximately 35 percent of graduating seniors leave high school with some college credit thanks to CCP.

CCP is still relatively new, which makes measuring long-term student impacts difficult. Nevertheless, the audit found some positive trends. As of 2021, nearly 8,000 associate degrees and certificates had been awarded to CCP students while they were still in high school. CCP participants earn on average approximately fourteen college credits (which is equivalent to one semester of college), and most earn at least six. Students who participate in CCP are more likely to enroll in higher education after high school—approximately 68 to 78 percent did so, compared to only 53 percent of non-participants in 2016 and 2017—and college dropout rates among CCP participants were significantly lower than those of non-participants in the classes of 2016 and 2017. There is, of course, some “selection bias” in these comparisons, as students have to meet academic readiness benchmarks before they can participate in CCP, but these are still positive signs of the program’s impact.

And then there’s the money. According to the most recent annual report, Ohio students and families have saved more than $833 million in tuition costs since CCP was established, with nearly $160 million saved during the 2020–21 school year alone. The average participant (who, don’t forget, earns approximately fourteen credit hours) saves roughly $4,400 in tuition, fee, and textbook costs.

One persistent criticism of CCP is that highlighting all this savings is misleading; critics have pointed out that if participants end up spending four years at college anyway, taking the same number of courses as non-participants, they don’t actually save any money in the long run. But the audit refutes that assumption. After reviewing the total number of credits students had earned at the time of graduation or program completion, the audit team found that CCP students who earned associate and bachelor’s degrees in 2021 graduated with roughly the same number of credit hours as their peers who did not participate in CCP, despite entering college with already-earned credits. This means the program actually does save students money, as it allows them to take (and pay for) fewer courses while pursuing a degree. It’s also worth noting that money isn’t the only thing that’s saved; time is also a factor. Fewer required courses mean students have more flexibility to meet family obligations, work a part-time job, explore work-based learning opportunities like internships, or graduate early.

The bad: A lack of oversight could be impacting participation

One of the most troubling takeaways from the audit came via interviews with ODE and ODHE, which revealed that because “there is no formal compliance or oversight function for CCP” established in law, the agencies “are not required to, and have chosen not to, take the initiative necessary to follow through with compliance-related activities.” This lack of program-level oversight means that no one is actively working to ensure that participating schools are complying with program requirements—and as a result, a lot of schools aren’t.

The audit found that there are “significant levels of non-compliance with program requirements among school districts.” For example, although state law requires districts to initiate CCP communication starting in sixth grade, surveys conducted as part of the audit revealed that almost half of districts—43 percent—didn’t start communication until high school. Their failure to follow the law is likely impacting participation, as districts that reported beginning their communication efforts prior to high school had a 14 percent higher CCP hours per student value. The audit found similar non-compliance issues regarding digital information access. Districts are required by law to promote the program on their website, but approximately 37 percent reported that they didn’t. Those that did had an 8 percent higher CCP hours per student value.

It’s worrisome that districts’ failure to communicate could be preventing some kids from accessing CCP and its benefits. But it’s even more troubling that feedback from program participants suggests that some districts may be actively discouraging students from participating. Consider the following examples:

The upshot? In the absence of strong and consistent oversight by the agencies responsible for overseeing this program, students and families all over the state could be losing out on the potential benefits of dual enrollment.

The ugly: Traditionally underserved groups are missing out on CCP’s benefits

Dual-enrollment programs can play a crucial role in closing educational equity gaps, as they give students the opportunity to access higher-level coursework and earn college credit for free. Unfortunately, traditionally underserved students—especially low-income and minority students—participate in CCP at a lower rate than their peers. For example, although Black students made up 17 percent of the overall high school population during the 2020–21 school year, only 5.5 percent of high schoolers participating in CCP were Black; Hispanic students made up 6.7 percent of the high school population, but only accounted for 1.5 percent of CCP participants. Participation gaps for low-income students are even worse. In 2021, nearly half of Ohio students met the criteria for being considered economically disadvantaged, but those students made up only 17 percent of CCP participants.

The audit identifies several factors that could be contributing to these gaps:

Unfortunately, as the section regarding a lack of state oversight indicates, these aren’t the only barriers faced by low-income and minority kids. These populations of students would benefit the most from CCP courses, and yet they seem to be the least likely to have access to the program. Addressing the obstacles outlined above (and ensuring that schools are adequately preparing students for college-level work) would likely go a long way.

***

Overall, there’s plenty to celebrate in this audit. That includes the audit itself, which shines a welcome light on plenty of aspects of CCP that either weren’t included in the state’s annual report or were mentioned only in passing. But there’s also a lot to be concerned about. The lack of oversight is troubling. State policymakers would be wise to use the upcoming budget to add provisions to state statute that require ODE and ODHE to hold schools accountable for following the law. As for the participation gaps for low-income and minority students, the state’s attempts to address the issue are a good start, but both state leaders and those at districts, colleges, and universities can and should do more—and the best place to start would be tackling achievement and readiness gaps starting as early as possible.

Credentials matter, but maybe not as much as many hope. That seems to be one of the takeaways from Fordham’s latest report by Matt Giani evaluating high school industry recognized credential (IRC) attainment and learner outcomes in Texas. Amongst other findings, it concludes that while IRCs have some benefit in terms of learners’ postsecondary and workforce outcomes, they are not “transformational.” For instance, only credentials in several areas (IT, Health Science, Business and Arts, and A/V) are linked with postsecondary success. And a credential in Cosmetology is an impediment to such success.

I won’t rehash the report’s other findings. The research is worth checking out on its own and represents a welcome addition to the IRC conversation. Indeed, it provoked some reflection on our part at ExcelinEd about the Credentials Matter work that we undertook a couple years ago. In it, we found that states are all over the map when it comes to the alignment of credentials with employer demand. Consider that only 18 percent of credentials earned by K–12 students were aligned with employer demand and associated with careers paying a minimum of $15/hour. (The Fordham report does not evaluate the demand by employers of the IRCs on Texas’s list.)

Fast forward to the present. More states are doubling down on IRCs as a metric for career readiness, not just Texas. So what should policymakers and state leaders know about the promise and pitfalls credentials?

Here are three things we learned during our work on Credentials Matter.

1. Industry recognized credentials are not created equally, but too many states treat them as such. Some are focused on general skills like workplace safety, while others demonstrate real occupational preparation. Some are aligned with postsecondary study and sustainable wages, while others are dead ends. In Texas’s list, mature credentials in IT from Google and CompTIA coexist with basic food safety credentials. A Licensed Medical Radiological Technologist credential carries the same weight as a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA). Occupationally, the former pays a median wage of $29.50/hour, while the latter pays just $14.57/hour (for folks familiar with Texas, that’s $3.50/hour less than a car wash attendant at Bucc-ees). Texas is not alone in its treatment of IRCs. It is no wonder that IRCs are not “transformational” when there is too little differentiation of their value to learners, families, and economies.

2. IRCs are just one element of a high-quality pathway. We support states prioritizing employer valued credentials aligned to family-sustaining wage occupations. But we also recognize that the pathway to such occupations requires core academic proficiency, a range of work-based learning experiences, postsecondary credential attainment (of some sort), and learner supports for pathway advising and navigation. When states place too heavy of an emphasis on IRCs alone, there is no guarantee that these other elements exist or are accessible to all learners. Or when states promote “dead end” credentials as indicators of “readiness,” they are admitting that perhaps a high-quality pathway isn’t for all students. As we point out in Pathways Matter, learners take different journeys from education to workforce, but that should not limit their future aspirations and ability to support a family.

3. There are too many assumptions about IRCs and learner pathways, and not enough facts. If it seems that we are picking on certain credentials (CNA and Cosmetology, for instance), we do so for good reason: We’ve heard too many providers make assumptions about what’s going to happen to learners who earn them. A certified nursing assistant can go on to be a registered nurse. A cosmetologist can go on to own a business. A pharmacy technician can go on to be a pharmacist. Sure, they can. But do they? The gulf between the knowledge and skills needed for a CNA to be an RN, for a cosmetologist to be a business owner, and for a pharmacy tech to be pharmacist is vast. And one cannot assume that an IRC, and the pathways experiences learners are provided, are sufficient to bridge that gulf. In most states, there are nothing but anecdotes to back up these assumptions. No hard data, no assurances to learners and their families that these leaps are achievable. In fact, most states cannot answer basic questions about what happens to learners who choose certain pathways over others.

So what can states do to create pathway experiences that are transformational for learners? They can start by conducting a Return on Investment Analysis of learner pathways spanning K–12, postsecondary, and the workforce—to know how well their current offerings are working. The analysis provides an opportunity for states to set priorities for what a high-quality learner pathway should include, to identify a core set of metrics—not just one proxy—for evaluating offerings, and to make longer-term systemic improvements that guarantee learners economic mobility and security down the road.

Credentials do matter, but pathways matter more.

Sylvia Allegretto and her colleagues at the union-backed Economic Policy Institute (EPI) have been arguing for over eighteen years that teachers are underpaid. Her latest in a long line of reports on the topic was published in August and follows the same methodology as all previous versions.

Using data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), Allegretto compares teacher wages and benefits in all fifty states and the District of Columbia to those of a large group of workers in a BLS classification known as “civilian professionals.” This is, Allegretto writes, the “broadest category available that corresponds with all college graduates,” and thus is felt by EPI to be the most directly comparable with teachers. Wages comprise regular pay as reported to the IRS, which includes both direct pay for hourly or salaried work and supplemental pay for things like overtime, bonuses, profit-sharing, and paid leave. The benefits category includes health and life insurance, retirement plans, and payroll taxes such as Social Security, unemployment, and workers’ compensation. All forms of compensation are reported on an earnings-per-week basis, which Allegretto says adjusts for the fact that most teachers do not receive pay for their regular jobs during the summer. My Fordham colleague Aaron Churchill took issue with this methodology upon the release of a previous version of this report in 2016, partly because it assumes that all bachelor’s degrees represent a similar level of skills, and also because it ignores the fact that, even during the school year, teachers report working fewer hours than other professionals.

The findings from 2021 are in line with EPI’s earliest analysis. To wit, teacher wages lag that of civilian professionals, just as they have done in every studied year since 1996. In 2021, the wage gap between the two groups was the largest EPI’s analysts have ever seen: 23.5 percent. It is, as ever, headline news.

Inflation-adjusted average weekly wages of teachers have been relatively flat since 1996—increasing just $29 between 1996 and 2021—while the comparison group of college graduates rose by $445. Allegretto notes that there have been some time periods when the gap narrowed and others when the gap increased, generally based on broad economic trends. She wisely points out that wage volatility—both upward and downward—impacts teachers less than civilian professionals because teacher pay scales are set by long-term contracts. Allegretto also discusses pandemic labor market disruptions, concerned that they could distort the methodology EPI has been using. However, data suggests that college-educated workers were much less affected by the pandemic than were other workers. Thus, the previous methodology remained in place with the caveat that “any pandemic-related issues with the data that come to light will be addressed in future updates.”

Benefits are, unsurprisingly, higher for teachers than for the comparison group. This has also been a steady trend over all the years of study. In 2021, the benefits gap favoring teachers was at the highest level ever seen: 9.3 percent. Combining the wage and compensation gaps results in a total compensation gap of 14.2 percent, with civilian professionals coming out on top.

Allegretto includes numerous breakdowns of the wage differential by itself—male teachers fare worse than females, teachers in Colorado have a far larger gap than their peers working in Rhode Island, etc.—but not for the combined wage/benefits differential. Those data would likely impact the conclusions of the report and perhaps change the headlines they generate.

The Fordham Institute reviewed EPI’s first report on teacher compensation back in 2004. Their methodology hasn’t changed and neither have our quibbles with it. The comparison group of workers is needlessly broad; the difference between free market and union-negotiated wages and benefits is treated as a statistical quirk rather than a heavy thumb on the scale of supply and demand; and teacher scheduling (school day schedules, summers off, etc.) is averaged out of the equation, despite it likely being a hugely valuable non-monetary incentive for many teachers (not to mention the popularity of those schools with four-day weeks).

There’s another unanalyzed factor to consider that’s become a larger issue recently. With baby-boomer teachers retiring en masse, the average teacher is much younger and less experienced than in previous years. This “composition effect” drives down average salaries. But that’s a statistical mirage, as the inflation-adjusted pay for teachers at any given point on the pay scale (new teachers, ten years of experience, etc.) is up sharply. Comparing teachers to workers with similar skills and similar years of experience would significantly change the outcome.

But to add a new question into the ongoing discussion: What if we assume for a moment that EPI’s analyses have all been right and that their overriding call throughout the years—more pay for teachers!—should have be heeded following the release of at least one of these recurring reports since 2004. Why hasn’t it? Each iteration of these EPI reports has concluded with some tie in to current events to attempt to ground and amplify that call. “Now more than ever...” But neither housing bubble nor Race to the Top nor Great Recession have done anything to change the trajectory of teacher wages and benefits, nor the gap between them and their nonteacher professional peers. Why not? Now that would be some valuable research. Perhaps the latest call—tied to a putative teacher shortage—will be the one that finally works to get policymakers to see the light. Or perhaps it won’t.

SOURCE: Sylvia Allegretto, “The teacher pay penalty has hit a new high,” Economic Policy Institute (August 2022).

For years, millions of U.S. students have taken the NWEA MAP Growth assessment. Data from these computer-adaptive assessments—which cover math, reading, language usage, and science—can help teachers determine which students need remediation or other supports and in which topic areas. This has been particularly important in the wake of Covid education disruptions beginning in spring 2020, which sent achievement levels plummeting; the need for supports to remediate that epic learning loss continues today. A new analysis, conducted by the organizations involved in its implementation, looks at an ambitious effort to boost MAP achievement.

Starting in 2018, NWEA teamed up with online education provider Khan Academy to develop a tool to help increase student achievement on MAP Growth’s mathematics assessments. Called MAP Accelerator, it uses previous achievement data to create supplemental content customized for each student. It is geared toward helping students build skills up to mastery level using a combination of video instruction and intensive practice lessons with detailed performance feedback, gradually moving students on to higher and harder content.

MAP Accelerator was rolled out to NWEA-participating schools in fall 2020, coincidentally just when evidence of Covid-related learning loss was beginning to surface. Ninety-nine districts participated. Analysts reviewed data from more than 181,000 students in grades three through eight who utilized the tool in 2020–21. There was a roughly even split between males and females; 34 percent were White, 12 percent were Black, 5 percent were Asian, and a noteworthy 35 percent were Hispanic. The authors make clear that this is not a nationally-representative sample and wasn’t intended to be, as the MAP Accelerator is marketed as a support for traditionally-underserved students. Fifty-two percent of students in the study sample attended schools where the majority of students are eligible for free or reduced-price lunch.

The analysts use a quasi-experimental, pre-test post-test design. Random assignment was not possible, so analysts instead broke students into four groups: no usage, less than fifteen minutes of usage per week, fifteen to thirty minutes of usage per week, and more than thirty minutes of usage per week. They utilize “judicious” statistical controls to help mitigate confounding variables and look at outcomes of other non-math MAP Growth assessments to attempt to identify and control for selection bias.

Only 5 percent of students used MAP Accelerator at the recommended dosage of thirty or more minutes per week. Most students (45 percent) fell into the less than fifteen minutes per week category. A whopping 41 percent did not use the tool at all. Students in the highest-usage group spent, on average, about three twenty-minute sessions per week over twenty-four weeks. While all groups showed growth in test scores from fall 2020 to spring 2021 (based on whatever their pandemic-impacted starting point was), the highest-usage group registered growth that was 0.26 standard deviations higher on average than similar students who used the platform for less than fifteen minutes per week. This general trend was consistently observed regardless of student race and ethnicity, gender, and school eligibility for free or reduced-price lunch.

While there was little evidence of self-selection bias, some evidence of other confounding variables was detected. Adjusting for these pointed to a large and statistically significant boost in math achievement based directly on the amount of accelerator usage (e.g., practice on geometry led directly to an increase in achievement on the geometry assessment). Impacts were significantly lower for students hailing from districts with greater than 20 percent English language learners. The analysts note that findings for poverty level and English learner status were at the school level rather than at the student level, rendering them less accurate.

We must be careful not to read more into these data than is here. First and foremost, this is not a randomized control trial. But equally important, would even the non-causal outcomes observed have looked the same in a normal school year? All of the students involved had been impacted by the pivot to remote learning in spring 2020, and most had seen their math achievement plummet as a result. We have no data on which students in this study had returned to in-person learning by the fall or spring, nor which students had access to broadband internet and connected devices.

All we can safely conclude is that concentrated practice with the MAP Accelerator appeared to increase achievement on MAP math assessments beyond what would have been expected without their use. But this is good enough news for now. Heaven knows we’re very clear about the problem; we need more data on possible solutions, and this one looks very promising so far.

SOURCE: Kodi Weatherholtz, Phillip Grimaldi, and Kelli Millwood Hill, “Use of MAP Accelerator associated with better-than-projected gains in MAP Growth scores,” Khan Academy and NWEA (August 2022).

Teachers are the most important in-school factor affecting student achievement, and in the wake of pandemic-caused learning losses, Ohio schools need effective teachers more than ever.

But hiring and retaining teachers is easier said than done, even in the best of times. Longstanding issues around licensing and compensation keep talented individuals away from the profession.

Our latest policy brief, third in a series of papers, addresses teacher-pipeline and teacher-retention issues which are critical if Ohio wants to make teaching an attractive and financially rewarding career option for more young people. In this paper, we focus on several ways that Ohio policymakers can better attract talent and strengthen the state’s teacher workforce.