This being a budget year, state lawmakers will soon be delving into the minutia of school funding. To help inform these discussions, we’ve begun a series looking at Ohio’s funding system, including a deep-dive into the new formula that lawmakers enacted in 2021 and which Governor DeWine has proposed to maintain. The first essay provided a basic orientation to the state’s funding system and the new formula, known as the Cupp-Patterson or Fair School Funding Plan. The second essay examined the “base cost” model, a set of calculations that yield districts’ base amounts. When used in tandem with the state share mechanism, the base amount drives core state funding allocations for districts, as the figure below indicates.

But what is the state share? Basically, it’s an “equalizing” mechanism that ensures state dollars “level-up” poorer districts. The state picks up—as it should—a larger portion of base funding for poorer districts, while it covers less in wealthier districts that can raise more dollars locally (including a minimum 2 percent, or 20 mill, state-required property tax). While the concept of the state share is straightforward, implementing it remains a complicated task. In this piece, we’ll unpack this element, as well as look at some technical challenges that deserve attention.

Measuring district “capacity” and calculating the state share

The new formula (and its predecessor) relies on property values and resident income to measure districts’ wealth. Property values makes obvious sense, as they directly impact how much districts can generate locally through property taxes. Income is somewhat less intuitive, but the idea is that higher-income districts are more likely to gain voter approval for higher property tax rates, further enhancing their capacity to raise local dollars.

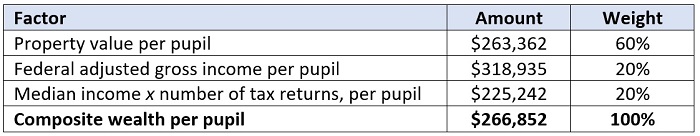

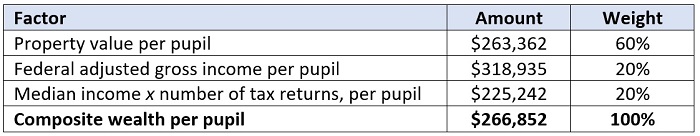

The trickier part is how to use these data in a formula. The pre-2021 version inconsistently used income in the state share calculations, as it only played a role in certain districts whose incomes were low relative to their property values. The new formula is more consistent, applying both factors in all districts’ calculations. Using data for Columbus City Schools, table 1 illustrates how the data are combined to create a composite wealth measure for the district. Two slightly different measures of income are used: 1) the total federal adjusted gross income of a district’s residents, and 2) a district’s median income multiplied by the number of state tax returns filed by its residents.

Table 1: Calculating a composite per-pupil wealth for Columbus City Schools, FY 2023

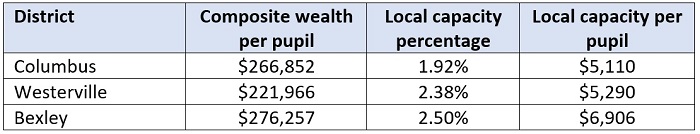

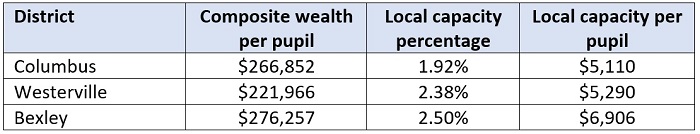

Things get more complicated after this. Step two of the new methodology calculates a district’s median income relative to the state median. Columbus, a district with below average income, has a “median income index” of 0.85, while a high-income district like Bexley has an index of 2.05. This index is then multiplied by specific numbers to yield a “local capacity percentage.” This appears to be the local tax rate the state assumes districts have the capacity to levy. That said, it’s odd to see assumed tax rates under 2 percent, such as Columbus’s, since Ohio law requires all districts to assess a minimum property tax of that rate. Nonetheless, as table 2 shows, this generates a per-pupil local capacity amount—the portion of the base that the state presumes a district can cover. Note that this amount doesn’t determine districts’ actual local funding; it’s used only for formulaic purposes.

Table 2: Calculating local capacity amounts for three Franklin County districts, FY 2023

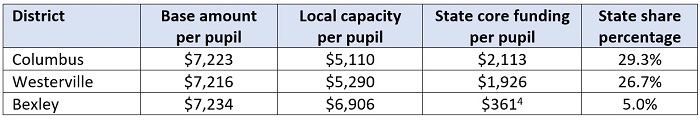

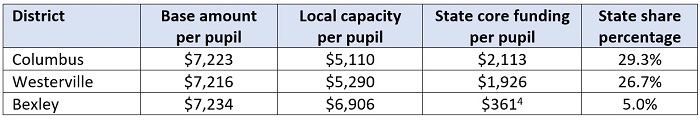

In step three, the local capacity per pupil is then subtracted from the base to produce the base state funding allocation. From that, the state share percentage is derived. As Table 3 indicates, the wealthy district of Bexley has a lower state share (and thus receives just $361 per pupil in state aid), while its poorer neighbors receive more state funding.

Table 3: Calculating the state share percentage for three Franklin County districts, FY 2023

How will the state share function over time?

Though obviously complex, the state share does work to identify the state’s neediest districts and steers more aid their way. But how might this mechanism function over time? Here, there seems to be less clarity.

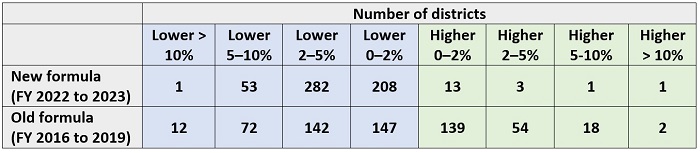

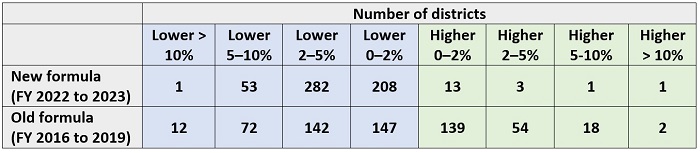

To begin, table 4 reveals a striking pattern in districts’ state share percentages between 2022 and 2023—the first two years for the new model. We notice that nine in ten districts experienced declines in their state shares (meaning they were deemed wealthier under the formula in 2023 than in 2022), while only eighteen of roughly 600 districts registered an increase in state share (meaning they got poorer). Interestingly, nothing like this occurred under the old, pre-2021 formula. There was a greater balance of gains and losses from 2016 to 2019, the last year it was used.

Table 4: Changes in districts’ state share percentages under the new and old formulas

Note: Forty-five districts had no change in the state shares from 2022 to 2023 (they were all at the floor in both years), and twenty-one districts had no change under the old formula from 2016 to 2019. The table displays percentage-point differences.

Note: Forty-five districts had no change in the state shares from 2022 to 2023 (they were all at the floor in both years), and twenty-one districts had no change under the old formula from 2016 to 2019. The table displays percentage-point differences.

Two factors seem to explain the systemic declines in the state share from 2022 to 2023.

One is inflation, along with the new formula’s stronger emphasis on “absolute” wealth. Nearly all districts registered higher property values and incomes in FY 2023—partly due to inflation—and thus districts systemically looked wealthier. While inflation was tamer then, how did the old system avoid a system-wide decline in state shares due to inflation? One likely explanation is that it took a more “relative” approach to measuring wealth, whereby a district’s income and property values were compared to the state average. Thus, districts that gained wealth—but at a slower clip than the statewide trend—were actually deemed poorer and in need of more aid. Piqua school district, for example, had a 1.3 percent increase in property values from 2016–19, a rate below the statewide median of 8.3 percent. Thus, its state share rose.

One complaint about the relative concept was that trends in other parts of the state could impact a district’s measure of wealth. That was felt to be unfair. Thus, the new system takes a more “absolute” approach, where each district’s wealth is measured on its own terms (see table 1). That, however, creates an issue in which inflation will steadily make every district look wealthier over time, as they all begin to look “rich” by today’s standards.

The plot thickens with a second factor—a virtually fixed base amount—also playing a role in the declining state shares. With the exception of enrollment data, the state did not update the “inputs” of the base cost model (e.g., applying more recent teacher salaries). This resulted in very little change in districts’ base amounts from 2022 to 2023. Combined with the increasing local wealth, that led to declines in the state share percentages. The top rows of the table below illustrate how this occurs with hypothetical data. If the base amount remains constant over time, state shares slide as local wealth increases. In such a scenario, the state’s funding obligations under the formula would become less and less, presumably leading to funding reductions or perhaps increased use of “guarantees” to fund districts. However, when the base increases over time, inflationary gains in local capacity put less downward pressure on the state share percentages. The bottom rows of the table illustrate this scenario.

Table 5: Illustrating the interaction between the base amount and state share percentage

Note: The median district’s base amount in FY 2023 is about $7,300 per pupil, and the median district’s local capacity is about $3,900 per pupil. As shown in table 3, the local capacity per pupil is currently being calculated against the roughly $7,300 per-pupil base, not a “phased-in” base amount.

Note: The median district’s base amount in FY 2023 is about $7,300 per pupil, and the median district’s local capacity is about $3,900 per pupil. As shown in table 3, the local capacity per pupil is currently being calculated against the roughly $7,300 per-pupil base, not a “phased-in” base amount.

Raising the base seems to be critical for long-term functioning of the formula. But here’s the twist. Ohio isn’t actually funding schools at the full base amount of roughly $7,300 per pupil. Instead, it’s currently somewhere around $6,500 per student, reflecting the phase-in of the large, $2 billion-per-year increase in state spending called for under the new formula—additional outlays that the last General Assembly determined there weren’t enough resources to fully fund. Even with a partial phase-in of the spending increase during 2022 and 2023, lawmakers are still going to struggle to get the base to $7,300 per pupil in the forthcoming budget. Going above that amount is even more unlikely. What this means is that state shares could slide yet again in FY 2024 and 2025, leading to questions about how this whole thing will work over the long haul.

* * *

If you’ve gotten this far, you’ve probably concluded that this is all very complicated. You’d be right. The system is intricately designed, with a huge number of variables serving as “inputs.” Will it function and serve Ohio well over the long term? Or will it break down under the weight of its expense and complexity? No one knows the answer for sure, but it’s always possible that Ohio will end up with yet another “patchwork” formula—the very thing the proponents of this iteration desperately sought to fix.