The negative impacts of chronic absenteeism are well known. In elementary school, truancy can contribute to weaker math and reading skills that persist into later grades. In high school, where chronic absenteeism rates are higher, students who are chronically absent often experience future problems with employment, including being limited to lower-status occupations, less stable career patterns, higher unemployment rates, and low earnings. Across all grade levels, increased absenteeism has clear negative effects on both student test scores and social and emotional learning outcomes.

To prevent these negative outcomes, policymakers have done considerable work over the last decade to overhaul Ohio’s student attendance and absenteeism policies. Their efforts began in 2016 with the passage of House Bill 410. Among its many provisions, the legislation transitioned the state’s definition of chronic absenteeism from days to hours to ensure a more accurate measurement of how much class students are missing (and to align attendance policies with the state’s instructional requirements). It also required districts to adopt new or amended policies for how they would address student absences, to assign truant students to an absence intervention team responsible for creating a personalized intervention plan, and to notify parents if a student is absent with or without “legitimate excuse” for thirty-eight or more hours in one month (about six days) or sixty-five hours in a school year (about two weeks). Additionally, districts were prohibited from suspending or expelling students solely based on absences—a necessary change, as many districts had previously dealt with absenteeism by suspending truant students rather than attempting to help them.

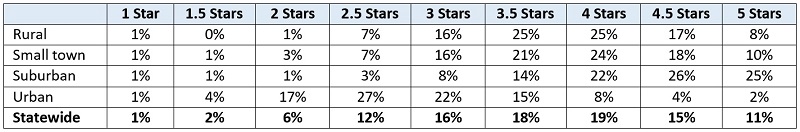

In 2017, Ohio leaders took things a step further by officially incorporating chronic absenteeism into state report cards. As part of its plan to comply with ESSA—the federal education law that replaced the No Child Left Behind Act—Ohio was required to add at least one additional measure of school quality or student success to its accountability system. Like a majority of other states, Ohio opted to add an indicator for chronic absenteeism, which it defines as missing at least 10 percent of instructional time for any reason, including both excused and unexcused absences. The indicator compares the chronic absenteeism rates of schools and districts to goals and benchmarks that are set for annual improvement. As of this year, the chronic absenteeism indicator contributes a possible five points to the Gap Closing component, which is one of five components on which districts are evaluated. Including chronic absenteeism in this way signals to districts that improving attendance should be a priority. But it also prevents attendance from being a deciding factor in districts’ scores. Chronic absenteeism is just one of eight indicators within the Gap Closing component, and one of dozens on the report card overall.

Still, these changes represented major steps forward. They improved how schools, districts, and the state track student absences. They held schools accountable for communicating with parents and supporting (rather than punishing) students. And they ensured that districts had a consistent incentive to improve chronic absenteeism rates. Most importantly, they did all this prior to the pandemic, when chronic absenteeism rates shot through the roof and made it abundantly clear that accurately measuring student attendance is crucial.

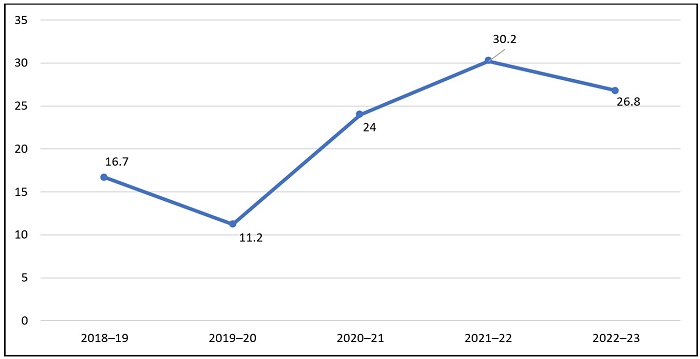

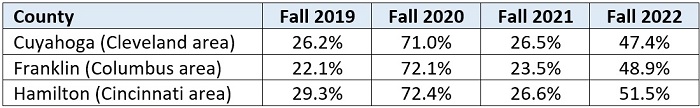

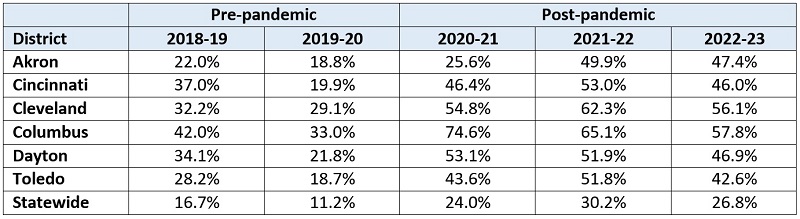

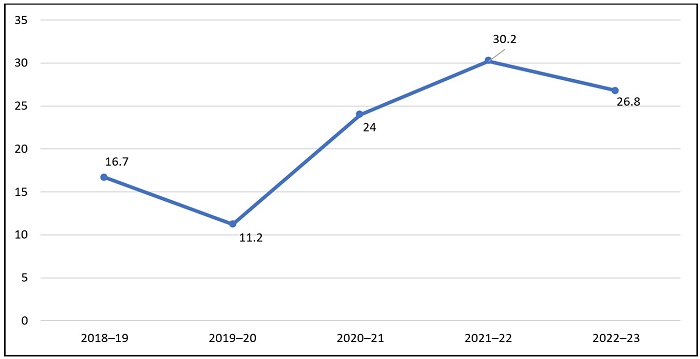

Consider the table below, which shows the state’s chronic absenteeism trends over the last five school years. Prior to the pandemic, Ohio’s chronic absenteeism rate was well below 20 percent. During and after the pandemic, though, rates shot up, and reached a whopping 30 percent in 2021–22.

Figure 1. Statewide chronic absenteeism rate, 2018–2023

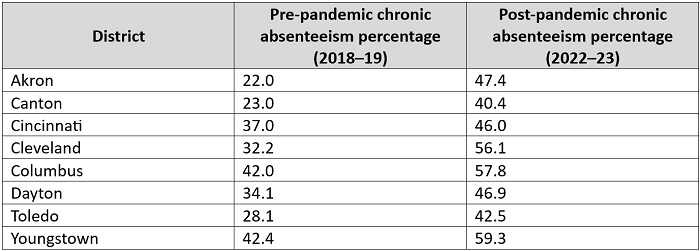

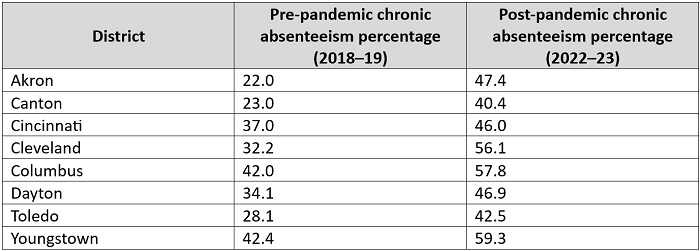

Things look even worse for high-poverty districts. The table below provides the pre- and post-pandemic chronic absenteeism rates in the Big Eight, the state’s largest urban districts. In each district, the most recent rates are markedly higher than they were pre-pandemic. In at least three districts—Cleveland, Columbus, and Youngstown—the chronic absenteeism rate is well above 50 percent. That means the majority of students enrolled in these districts are missing enough school to be identified as chronically absent.

Table 1. Pre- and post-pandemic chronic absenteeism percentages in the Big Eight

It’s important to remember what these sky-high percentages mean. It’s not just that students are missing a few classes. It’s that huge numbers of them are missing at least 10 percent of their instructional time, possibly more. That would be egregious enough on its own. But given how important instructional time is to helping students catch up from pandemic-caused learning loss, these percentages are horrifying.

With these data in mind, it is essential that Ohio stays the course. Districts and the state must continue their rigorous absenteeism tracking efforts so that we know how severe the problem is statewide, which districts are struggling most, and how the numbers are—or aren’t—improving over time. Districts and schools need to renew their commitment to consistent parental notification and the intervention efforts required under law.

Unfortunately, lawmakers are considering doing the opposite. A recently proposed amendment to Senate Bill 49 recommends making several troubling changes to existing school attendance laws.

First, the amendment seeks to establish a list of “legitimate excuses” for a student’s absence from school. Such excuses would include all of the following:

- Illness of the student

- Illness in the family necessitating the presence of the student

- Quarantine in the house

- Death of a relative

- Medical, behavioral, or dental appointment

- Observance of religious expression days

- College visitation

- Pre-enlistment reporting to a military enlistment processing station

- Placement in foster care or change in foster care placement or any court proceedings related to the student’s foster care status

- Student homelessness

- Deployment activities of a parent or guardian

- Participation in scheduled 4-H and FFA activities or programs

- Farm work of the parent or guardian during a time of year in which the amount of work to be performed is exceptional

- Inability of the parent or guardian to employ help in the family business, as determined by the district superintendent

- Emergencies or any other set of circumstances which, in the judgment of the school district superintendent, constitutes a good and sufficient cause for absence

Obviously, this is a huge list, which is a problem in and of itself. As the Department of Education has pointed out, missing too much school has “detrimental effects on a student’s learning trajectory,” regardless of whether an absence is excused or unexcused. Some of the issues in this list might be understandable reasons for absence—kids do get sick and family emergencies do arise—but whether the absence is understandable doesn’t change the fact that it’s still an absence. When kids miss school, they miss instructional time, and that can have short- and long-term academic consequences. Those are consequences we can’t afford in the wake of pandemic learning loss. Even worse, some of these things—like a parent’s inability to employ help in the family business—should not be considered a legitimate reason for a child to miss school. Homeless students and children in foster care might miss more class than their peers due to circumstances that are outside of their control, but counting those absences as excused and failing to track them (more on this below) does nothing to help those students. Given the awful chronic absenteeism numbers on this year’s state report cards, the last thing the state should be doing is offering districts and parents a mile-long list of all the reasons why it’s OK to miss school.

Second, the amendment would specify that the first cumulative sixty hours that a student is absent from school with a legitimate excuse cannot be factored into habitual truancy determinations. This change would torpedo state and district efforts to intervene with frequently absent students by allowing them to miss sixty hours—approximately nine days, or nearly two weeks—of school for “free” before districts start counting their absences.

Third, the department would be prohibited from including absences for which a student has a legitimate excuse in the calculation for the chronic absenteeism indicator on school report cards. This change would render the state’s effort to hold districts accountable for improving their attendance rates essentially useless by incentivizing them to encourage students and parents to provide “legitimate” excuses for absences. Under current law, students are labeled chronically absent if they miss at least 10 percent of instructional time for any reason. That amounts to roughly 100 hours for students in grades 7–12, and ninety hours for students in grades K–6. Under the proposed amendment, students could miss 10 percent of their school year but still not be considered chronically absent as long as they offered a “legitimate” reason.

Ohio can’t afford to take its foot off the gas when it comes to chronic absenteeism. The stakes for students are way too high. State leaders have done good work over the last decade to improve policies around data collection and intervention efforts aimed at keeping kids in school. Backing down from those policies now, when chronic absenteeism is at an all-time high and schools are still struggling to catch students up from pandemic-caused learning loss, is the wrong move.