“Social promotion,” the practice of pushing struggling students from one grade to the next regardless of their academic readiness, can have damaging long-term effects. Socially promoted students are at risk of falling further and further behind, which can lead to frustration and diminished social-emotional wellbeing. Studies consistently find that children who are socially promoted in elementary school continue to struggle as they move through middle school, and they drop out of high school at much higher rates, likely leading to a lifetime of hardship as adults.

Recognizing the harms of pushing students through school systems, national and state leaders have sought to eliminate the practice. President Bill Clinton once challenged American schools to “abolish social promotion.” As Texas governor, President George W. Bush advocated for policies that required schools to retain low-achieving students in certain grades.

Here in Ohio, Governor John Kasich championed the Third Grade Reading Guarantee, legislation that passed in 2012. The initiative required schools to retain and provide intensive interventions to third graders with severe reading deficiencies. During the years in which this policy was in effect, approximately 5 percent of third graders were retained. A recent study—consistent with findings from other states—indicates that retained students in Ohio benefitted from the extra time and support.

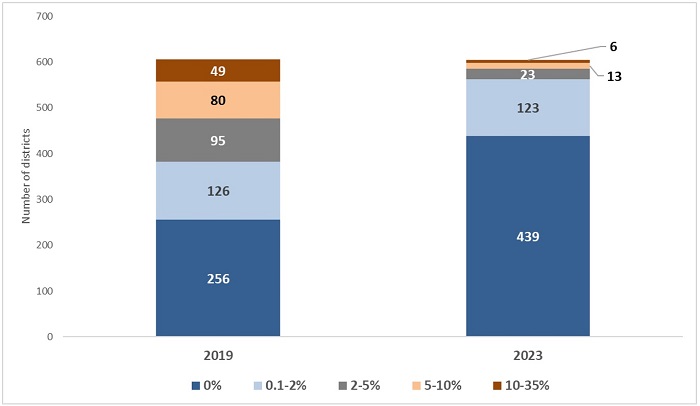

Despite the common sense, as well as the rigorous evidence supporting early-grade retention, state lawmakers succumbed to political pressure and gutted the Third Grade Reading Guarantee earlier this year via the state budget bill. With the requirement scrapped for 2022–23, retention was virtually non-existent across Ohio. Figure 1 shows that 439 out of 605 school districts retained not a single third grader, and another 123 districts retained less than 2 percent. Only a handful of districts (forty-two) had retention rates above 2 percent in 2022–23. By way of comparison, 224 districts held back more than 2 percent of third graders in 2018–19, the last year the requirement was in effect; almost fifty districts retained more than 10 percent of their third grade class that year.

Figure 1: Third grade retention rates across Ohio districts, 2018–19 and 2022–23

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: No district had a retention rate above 35 percent in either 2018–19 or 2022–23.

Source: Ohio Department of Education. Note: No district had a retention rate above 35 percent in either 2018–19 or 2022–23.

Such vanishingly low retention rates in 2022–23, which were also seen after 2021–22 when a similar Covid-era “safe harbor” from state requirements was in place, would be warranted if only a few students were struggling to read. But that’s not the case. On the contrary, tens of thousands of students are scoring limited, the lowest mark on state exams. Such students earn just a quarter of the points possible on the assessment, and are described as having “minimal command” of grade-level standards. Unless they receive serious intervention and supports, students at this level likely face a future with little opportunity for upward mobility.

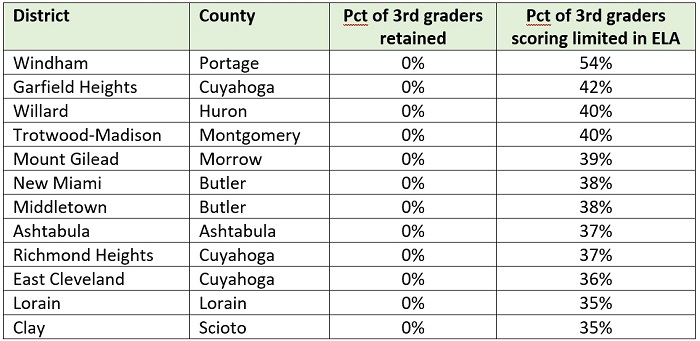

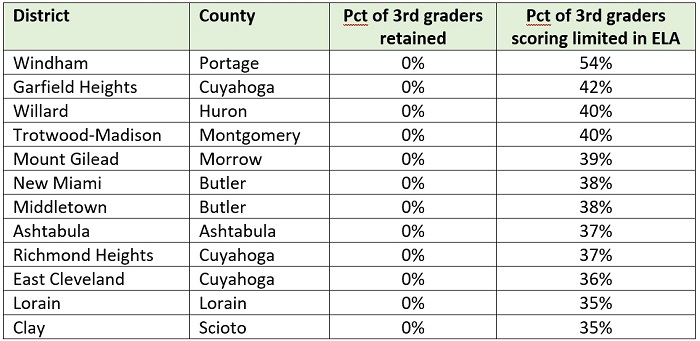

And yet, Table 1 shows a dozen districts that retained no third graders, despite more than one third scoring limited on their English language arts (ELA) exams. Urban districts such as Garfield Heights, Trotwood-Madison, and East Cleveland retained no third graders, while 36 to 42 percent scored limited. Similar results are seen in the small-town districts of Middletown and Lorain, as well as rural districts such as Mount Gilead and Clay. Such students, whose kindergarten and first grade years were disrupted by the pandemic, would certainly benefit from the extra time and support associated with retention.

Table 1: Districts with zero retentions, despite large percentages of limited students

* Statewide, 1.4 percent of third graders were retained, while 19.1 percent of third graders scored limited on their ELA exam in 2022–23.

* Statewide, 1.4 percent of third graders were retained, while 19.1 percent of third graders scored limited on their ELA exam in 2022–23.

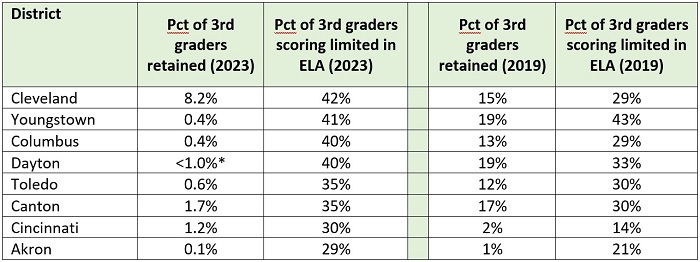

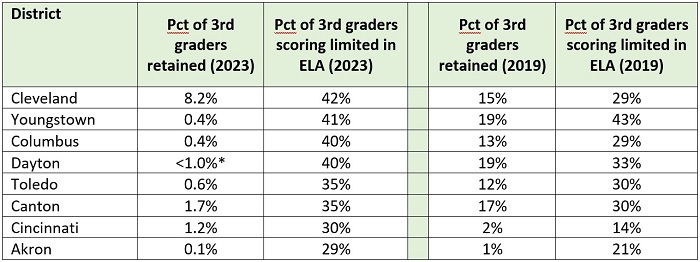

Though not among those with zero retentions, the Ohio Eight urban districts—locales with persistently low student achievement—promoted nearly all third graders, too. This occurred despite 30 to 40 percent scoring at the limited level on their ELA exams. Only Cleveland reported a relatively large number of retentions (8 percent), but that’s still far below its fraction of limited-scoring third graders. Moreover, as evident from the table, last year’s retention rates in the Ohio Eight were far lower than those in 2018–19—despite the growing percentage of limited students in seven of the eight districts.

Table 2: Ohio Eight districts third grade retention rates versus limited students, 2022–23 and 2018–19

* Dayton’s 2022–23 retention rate on its report card (50.1 percent) is a data-reporting error; according to the district, fewer than 1 percent of third graders were held back.

* Dayton’s 2022–23 retention rate on its report card (50.1 percent) is a data-reporting error; according to the district, fewer than 1 percent of third graders were held back.

These data are obviously disturbing. In many districts, anywhere from 20, 30, to 40 percent of third graders did not demonstrate even basic literacy skills on a state exam. Yet nearly all of them were promoted. Are these students receiving reading interventions this year? Will schools continue to push them along as they move into middle and high school? How many will drop out and fall through the cracks? Of course, retention doesn’t solve everything. But if Ohio had kept a reading guarantee in place for the 2022–23 school year, we’d have more confidence that schools were intervening to support struggling readers.

Unfortunately, this school year (2023–24) could be just as bad. That’s because the state is transitioning to a modified third-grade retention policy that requires schools to retain third graders who fall short of state reading standards—but, thanks to a new Texas-sized loophole, allows schools to consult with parents and receive sign-off for promotion. Given schools’ aversion to holding students back, many of them are likely to pressure parents into making such requests. It wouldn’t be surprising to see social promotion continue unchecked in the absence of a strict retention requirement.

While a return to a mandatory retention policy is theoretically possible (and would be laudable), it’s more likely that policymakers will need to find some middle ground that can help protect the interests of students who still need significant help in reading. Here are two ways to do that:

- The Department of Education and Workforce (DEW) should make sure that schools are carefully following the parental and intervention protocols outlined in the new retention law. The state’s modified retention policy requires the principal and reading teacher of a low-achieving third grader to consult with her parents before promotion to fourth grade. Through an audit-type process, DEW should verify that such consultations are occurring and that schools have evidence of a parental request for the child to move forward. DEW should also define and confirm that students promoted under this exemption receive “intensive reading instruction” in fourth grade, as called for under the revised policy.

- State legislators should tweak the Early Literacy component of the report card to ensure it does not incentivize social promotion. Under current policy, schools receive credit in the Early Literacy dimension of the report card when they promote students from third to fourth grade (i.e., their “promotional rate”). Including this measure may have been OK when there was a clear promotional standard. But including this rate under the revised policy is now more problematic, as it further incentivizes schools to push the parents of low-achieving children into making a promotional request. Conversely, schools choosing to take the tougher—though more student-centered—approach of retention are unfairly penalized because their Early Literacy rating is based in part on promotional rates. Lawmakers should either remove the promotional rate from the report card, or slightly modify statute to refer to the percentage of students who meet the state reading promotional bar (not the number of students actually promoted).

Just like handing out high school diplomas, universal promotion from third to fourth grade tends to make adults feel good. But there is nothing right about passing along children who can’t read. The Third Grade Reading Guarantee, in its original form, used to be a critical checkpoint ensuring that struggling readers got more help. That policy is in tatters, and the data reveal an unacceptable picture of widespread social promotion. Now we can only hope that state policymakers, school leaders, and parents will step up and work to root out social promotion, even in the absence of a requirement. Fingers crossed.