For the last half-century, if you read the mission statement of virtually any education reform organization, you will find earnest language about closing the racial or class achievement gaps. Unfortunately, not only have gaps failed to narrow during this multi-decade obsession, overall achievement levels have also remained mostly static. Indeed, a widely read 2019 Education Next study by Eric A. Hanushek, Paul E. Peterson, Laura M. Talpey, and Ludger Woessmann found that “the opportunity gap”—the relationship between socioeconomic status and achievement—has not changed over the past fifty years.

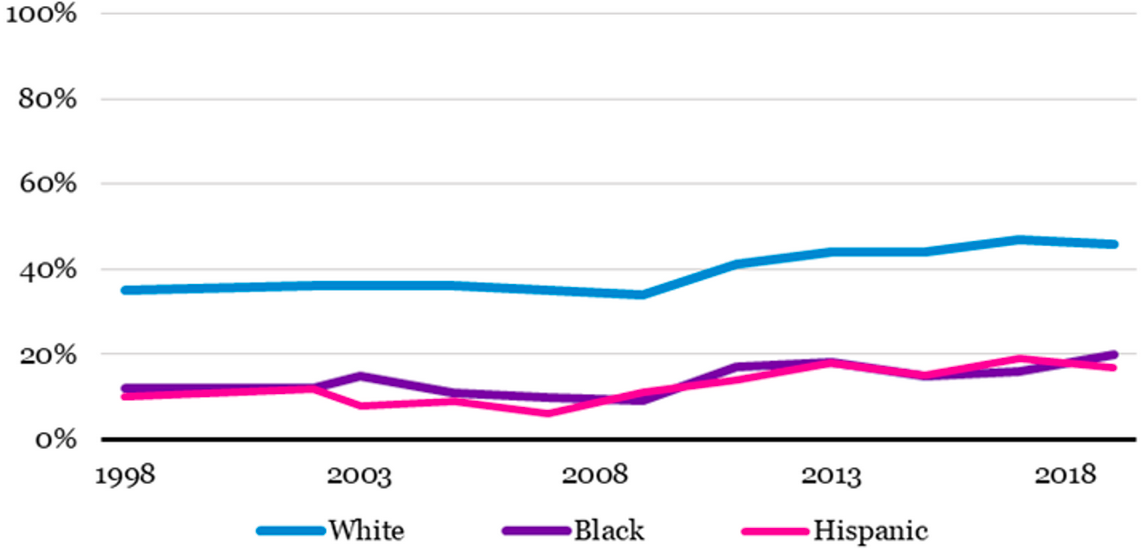

These macro results are not surprising. In May 2021, I was invited to provide testimony for the Rhode Island State Board of Education on how to improve educational outcomes. In preparation for the testimony, I pulled eighth grade NAEP reading proficiency scores for Rhode Island students since 1998. As is the case with most other states, in each year since the Nation’s Report Card was administered in Rhode Island in 1998, less than half of Rhode Island’s White eighth graders scored at NAEP’s proficient level in reading. As figure 1 shows, the racial achievement gap has essentially remained over that time. The sad irony is that closing the Black- or Hispanic-White achievement gap in reading, without improving outcomes for all students, would mean growing Black and Hispanic outcomes from sub-mediocrity to full-mediocrity.

Figure 1. Reading proficiency among eight graders in Rhode Island, by race, 1998–2018

Source: NAEP Data Explorer

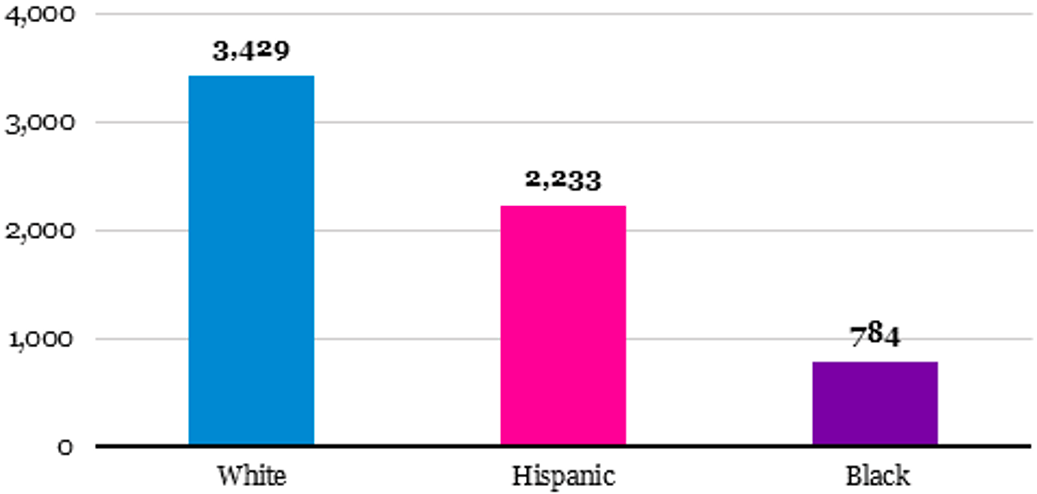

Also, in raw numbers, far more White students are failing. In 2019, nearly 3,500 White eighth grade students, 2,200 Hispanic students, and 784 Black students did not read at NAEP proficiency, based on the 2019 exam. (See figure 2.) Obviously White students make up a much larger segment of the overall population, and this explains their larger amount. But it is important to look at both proportional rates of success and actual student counts.

Figure 2. Number of Rhode Island eighth graders reading below proficiency, by race, 2019

Sources: NAEP Data Explorer and Rhode Island Department of Education

These data on reading proficiency—both in raw numbers and proportional rates by group—underscore our nation’s massive collective failure to effectively teach literacy and build verbal proficiency across all races and classes.

It also shatters the accepted truth that there is any sole or even primary cause of low proficiency rates among Black and Hispanic Americans. For example, systemic racism is unlikely the cause of such poor performance among White students. In my view, the multi-decade obsession with closing achievement gaps by certain categories has done something even worse: ushered in a mono-causal type of thinking that crowds out the ability to identify solutions across categories. If one believes systemic racism is the sole or primary cause of racial disparities, that tends to lead to a narrow universe of solutions that are focused mostly on race, as well. But that incomplete set of solutions has clearly not worked.

There is an alternative approach. Instead of a race- or class-based gap approach, imagine if the strategy was what some call “Distance to 100.” This would emphasize that the gap between 100 percent proficiency for all students and current performance levels is the gap that should be our dominant focus. Indeed, this approach would start with the question of why it is that barely one-third of all American students are reading at proficiency. To be sure, this isn’t to suggest that 100 percent is realistically attainable. Rather this is a lens through which we can view proficiency levels and measure how many children are behind where they should and can be. And that Distance to 100—almost 70 percent—is more than double the class and race-based achievement gaps.

If we adopted this approach, we would quickly discover that White students read below grade level for many of the same reasons Black and Hispanic students do. For decades, education researchers from E.D. Hirsch to Dan Willingham to Natalie Wexler have made the case that a lack of a focus on building knowledge in early reading instruction has had a devastating impact on all of America’s children. Natalie Wexler outlines the dilemma well in her book The Knowledge Gap: The Hidden Cause of America’s Broken Education System—And How to Fix It:

American elementary education has been shaped by a theory that goes like this: Reading—a term used to mean not just matching letters to sounds but also comprehension—can be taught in a manner completely disconnected from content. Use simple texts to teach children how to find the main idea, make inferences, draw conclusions, and so on, and eventually they’ll be able to apply those skills to grasp the meaning of anything put in front of them.

In the meantime, what children are reading doesn’t really matter—it’s better for them to acquire skills that will enable them to discover knowledge for themselves later on than for them to be given information directly, or so the thinking goes. That is, they need to spend their time “learning to read” before “reading to learn.” Science can wait; history, which is considered too abstract for young minds to grasp, must wait. Reading time is filled, instead, with a variety of short books and passages unconnected to one another except by the “comprehension skills” they’re meant to teach.

As far back as 1977, early-elementary teachers spent more than twice as much time on reading as on science and social studies combined. But since 2001, when the federal No Child Left Behind legislation made standardized reading and math scores the yardstick for measuring progress, the time devoted to both subjects has only grown. In turn, the amount of time spent on social studies and science has plummeted—especially in schools where test scores are low.

And yet, despite the enormous expenditure of time and resources on reading, American children haven’t become better readers. For the past twenty years, only about a third of students have scored at or above the “proficient” level on national tests. For low-income and minority kids, the picture is especially bleak: Their average test scores are far below those of their more affluent, largely white peers—a phenomenon usually referred to as the achievement gap. As this gap has grown wider, America’s standing in international literacy rankings, already mediocre, has fallen.

All of which raises a disturbing question: What if the medicine we have been prescribing is only making matters worse, particularly for poor children? What if the best way to boost reading comprehension is not to drill kids on discrete skills but to teach them, as early as possible, the very things we’ve marginalized—including history, science, and other content that could build the knowledge and vocabulary they need to understand both written texts and the world around them?

If we had a frame around “Distance to 100,” then we would focus on what’s required to improve everyone’s achievement and those transcendent factors that truly are holding all kids back—lack of access to content-rich curricula, unstable family structures, lack of school choice, and ineffective strategies to teach reading—which have a far greater cumulative impact than the sole factor of race or class.

As Hanushek et al. state, “The stubborn endurance of achievement inequalities suggests the need to reconsider policies and practices aimed at shrinking the gap. Although policymakers have repeatedly tried to break the link between students’ learning and their socioeconomic background, these interventions thus far have been unable to dent the relationship between socioeconomic status and achievement. Perhaps it is time to consider alternatives.”

Distance to 100 for everyone may be that empowering alternative.

Editor’s note: This was first published on Bellwether Education’s Eduwonk blog as part of a conversation between Ian Rowe and Sharif El-Mekki about what we’re actually talking about when we talk about race in the classroom.