Managing Talent for School Coherence: Learning from Charter Management Organizations

For almost five years now, the Center for Reinventing Public Education and Mathematica have teamed up to assess the

For almost five years now, the Center for Reinventing Public Education and Mathematica have teamed up to assess the

For almost five years now, the Center for Reinventing Public Education and Mathematica have teamed up to assess the effectiveness of charter-management organizations (CMOs). And a productive partnership it has been. Their latest report on this topic (the fifth, by Gadfly’s count) deserves attention. It focuses on how CMOs hire, train, and manage staff to maximize their schools’ instructional and cultural coherence; there are strong implications here for districts and other charters. Analysts found that successful CMOs managed talent in three key ways. First, they recruited and hired carefully, targeting pipelines like Teach For America and communicating clearly the school’s mission and work ethic. (Messaging, these CMOs believe, helps teachers self-select during the application process.) Second, they used intensive and ongoing socialization of team members, including routine observations and real-time feedback. Third, they aligned pay and promotion to organizational goals, meaning, for example, that stellar teachers were offered the chance to coach others, develop new programs at the schools, and more. CMOs also provided cash rewards to rock-star teachers which, interestingly, were based more on leaders’ professional opinions than assessments or performance metrics. The report draws a number of conclusions that district schools and other charters would be wise to follow insofar as they can.

SOURCE: Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross, Melissa Bowen, Allison Demeritt, and Robin Lake, Managing Talent for School Coherence: Learning from Charter Management Organizations (Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, June 2012).

We’ve long rued the state of American science education—and crammed worrisome evidence from national and international assessments (as well as our own evaluations of states’ science standards) into the ears of all who will listen. This follow-up report to the 2009 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) science test has us concerned all over again, both with what it says and with how its findings may be interpreted. It examines (for the first time) students’ ability to perform hands-on and interactive computer-based science tasks. Three key trends emerged: The majority of pupils could make straightforward observations of data (e.g., 75 percent of twelfth graders could test a water sample and note whether it met EPA standards). Yet they struggled when investigations contained multiple variables or required strategic decision making to gather appropriate data (e.g., just 24 percent of eighth graders could manipulate metal bars to determine which were magnets). Finally, though students could often arrive at the correct conclusion, they struggled to provide evidence for their answer. (Seventy-one percent of fourth graders could accurately choose how volume changes when ice melts into water but only 15 percent could explain why that happened using evidence from the experiment.) These stumbles have already elicited grumbles among reporters, government officials, and others. Their argument: These data are proof that we’re forcing too much content (presented via rote memorization), which is hindering students’ ability to reason. But, as esteemed biologist Paul Gross wrote earlier this week, “there is no reasoning, scientific or otherwise, in the absence of knowledge.” Yes, hands-on activities are a critical component of science education. But so is learning the content. Thankfully, the NAEP activities are designed to measure content knowledge, too.

We’ve long rued the state of American science education—and crammed worrisome evidence from national and international assessments (as well as our own evaluations of states’ science standards) into the ears of all who will listen. This follow-up report to the 2009 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) science test has us concerned all over again, both with what it says and with how its findings may be interpreted. It examines (for the first time) students’ ability to perform hands-on and interactive computer-based science tasks. Three key trends emerged: The majority of pupils could make straightforward observations of data (e.g., 75 percent of twelfth graders could test a water sample and note whether it met EPA standards). Yet they struggled when investigations contained multiple variables or required strategic decision making to gather appropriate data (e.g., just 24 percent of eighth graders could manipulate metal bars to determine which were magnets). Finally, though students could often arrive at the correct conclusion, they struggled to provide evidence for their answer. (Seventy-one percent of fourth graders could accurately choose how volume changes when ice melts into water but only 15 percent could explain why that happened using evidence from the experiment.) These stumbles have already elicited grumbles among reporters, government officials, and others. Their argument: These data are proof that we’re forcing too much content (presented via rote memorization), which is hindering students’ ability to reason. But, as esteemed biologist Paul Gross wrote earlier this week, “there is no reasoning, scientific or otherwise, in the absence of knowledge.” Yes, hands-on activities are a critical component of science education. But so is learning the content. Thankfully, the NAEP activities are designed to measure content knowledge, too.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Science in Action: Hands-On and Interactive Computer Tasks from the 2009 Science Assessment (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, June 2012).

Baking a successful school-choice soufflé is challenging. The ingredients are hard to come by: Schools must be high performing while simultaneously offering options to a diverse parent base. And the recipe is fussy: Navigating the system should be easy and fair. There can be no inherent incentives to game the system. Denver’s new school-choice program (creatively titled SchoolChoice) may not be “Iron Chef” quality, but it has some stimulating flavors cooked in. This encouraging report from A+ Denver explains: Last year, the Denver Public Schools (DPS) streamlined its choice program, merging all sixty of the district’s varying school applications and deadlines into one system. This alleviated much headache and caused an uptick in intradistrict choice. For the 2010-11 school year, over 22,700 students (comprising a little over 25 percent of all pupils) participated, with over two-thirds of them gaining access to their top-choice schools (and 83 percent to one of their top three choices). Even more promising, demand for a school was highly correlated with its quality. Improvements to the program can still be made, however. The report finds, for example, that poor and minority families choose schools that are generally lower performing than their better-off peers (likely due to school location and marketing). There’s lots to learn from the paper, including new insights about parental preferences and school-choice decision-making. As DPS refines its program—and as other districts seek to copy, and improve upon, its recipe—this report will offer helpful guidance.

SOURCE: Mary Klute, Evaluation of Denver’s SchoolChoice Process for the 2011-2012 School Year (Denver, CO: University of Colorado, prepared for the A+ Denver SchoolChoice Transparency Committee, June 2012).

Checker and Mike explain why individual charter schools shouldn’t be expected to educate everyone and divide over Obama’s non-enforcement policies. Amber analyzes where students’ science skills are lacking.

The Nation’s Report Card: Science in Action: Hands-On and Interactive Computer Tasks from the 2009 Science Assessment - National Center for Education Statistics

READ "How School Districts Can Stretch the School Dollar"

Despite some signs of economic recovery, school districts nationwide continue to struggle mightily. Nobody expects economic growth—or education spending—to rebound to 2008 levels over the next five years, and the long-term outlook isn't much brighter.

In short, the "new normal" of tougher budget times is here to stay for American K-12 education. So how can local officials cope?

In my new policy brief, I argue that the current crunch may actually present an opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of our education system if decision makers keep a few things in mind:

First and foremost, solving our budget crisis shouldn't come at the expense of children. Nor can if come from teachers' sacrifice alone. Depressing teachers' salaries forever isn't a recipe for recruiting bright young people into education—or retaining the excellent teachers we have. Finally, quick fixes aren't a good answer; we need fundamental changes that enhance productivity.

So how can school districts dramatically increase productivity and stretch the school dollar?

One, we should aim for a leaner, more productive, better paid workforce. Let's ask classroom teachers to take on additional responsibility in return for greater pay, eliminate some ancillary positions, and redesign our approach to special education.

Two, we should pay for productivity. A redesigned compensation system would include a more aggressive salary schedule, more pay for more work and better results, and prioritization of salaries over benefits.

Three, we must integrate technology thoughtfully. Online and "blended" school models are coming to K-12 education. They can be catalysts for greater pupil engagement, individualization, and achievement and, if organized right, they can also be opportunities for cost-cutting.

Many districts continue to face budget challenges of historic proportions. Rather than slashing budgets in ways that erode schooling, let's rethink who we hire, what they do, how we pay them, and how to incorporate technology—that's where the big payoff is.

Yesterday’s “exquisitely timed” GAO report set off an avalanche of accusations at charter schools for “discriminating” against students with disabilities with its finding that special-needs students represent a lower proportion of charter-school enrollment than they do in district schools. Representative George Miller, who requested the study, found the news “sobering.” Yet everyone already knows, as Eva Moskowitz told the Wall Street Journal, that the best charter schools try to help students with mild disabilities shed their labels (and Individual Education Plans) by improving their math and reading abilities. That could explain a significant part of the discrepancy. But there’s another point that’s overlooked entirely: No single public school is expected to serve students with every single type of disability. In fact, traditional public schools regularly “counsel out” students with severe disabilities because they don’t have the resources and expertise to serve them. Many school districts operate separate schools (or programs) precisely for those kids. Should the GAO put out a report blasting them for skirting their responsibilities? Of course not. What these districts are doing—what every school district of any size does—is to create special programs at particular schools that can better meet the needs of students with particular disabilities. Because, again, no single public school is expected to serve students with every single type of disability. Scratch that: Except for charter schools, which are somehow expected to do the impossible.

SOURCE: “Charter Schools Fall Short on Disabled,” by Stephanie Banchero and Caroline Porter, The Wall Street Journal, June 19, 2012.

A version of this article appeared as a blog post on Flypaper.

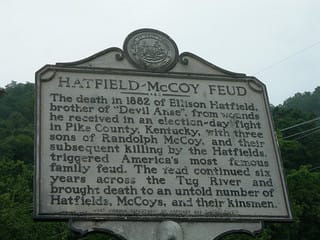

The infamous Hatfield and McCoy feud is an apt analogy for the history of district-charter school relations in Ohio. Neither side has much liked the other for years. Today, however, we see signs that the animosity and acrimony are fading.

The history of Ohio district-charter relations calls to mind legendary feuds. Photo by Jimmy Emerson |

Cleveland Mayor Frank Jackson shepherded legislation through the General Assembly that would, among a host of innovative reforms, provide high-performing charter schools in Cleveland with local levy dollars to support their day-to-day operations. Building on the momentum coming out of Cleveland, Columbus Superintendent Gene Harris put forth a plan that would share local property-tax money with some of that city’s high-flying charters in the form of grants to enable those schools to help boost the performance of low-performing district schools.

There are other Buckeye State examples. Reynoldsburg City School District, serving one of Columbus’s most diverse close-in suburbs, has quietly built a portfolio of school options for its residents over the past decade. Now it is opening those options to students from other districts who might want to attend a Reynoldsburg school. Further, a group of school districts (including Columbus, Reynoldsburg, and the Dayton Public Schools), educational service centers, and the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation have been working together to build a joint charter-school-authorizing effort. While legislation to advance this work has been scuttled twice by the Ohio House (due to furious lobbying by other Ohio authorizers), the partners continue to work together for the benefit of kids across their sponsored schools.

Obviously, not everyone is a fan of charter-district collaboration. There has been much angst expressed about the Cleveland plan by some of the state’s most militant charter supporters and union diehards. Yet Ohio is not alone in the effort to move its charter-district relations forward. In fact, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has offered $40 million in competitive funding for cities that commit to what they are calling “Charter-District Collaborative Compacts.” So far, such compacts are visible in sixteen cities, including Baltimore, Boston, Central Falls (RI), Chicago, Denver, Hartford, and Los Angeles.

In these communities, neither side is surrendering to the other—or trying to kill it. Rather, according to Gates’s Don Shalvey, both sides are “committed to quality for every student, expanded public school choices and a ‘can do’ spirit that honors teachers and the youngsters they serve.”

Both charter and district partners also commit to replicating high-performing models of traditional and charter public schools while improving, driving out, or closing down schools that ill-serve students. Decisions are driven by performance as opposed to politics or institutional interests.

In these compact cities, high-performing charters can access district facilities and, in some cases, even local funding. Districts benefit because their academic ratings can increase from the inclusion of test scores from high-flying charter partners. In some compact cities, the partners also commit to working together on such shared challenges as measuring effective teaching and implementing the Common Core.

Feuds die hard. But for the sake of the kids and grandkids, even the Hatfields and McCoys found peace. Children across Ohio (and those in other locales) will benefit if charters and school districts can end their scuffles and find ways to share expertise and resources and otherwise work together to break down barriers to more quality school choices.

A version of this article appeared in the Ohio Gadfly Bi-Weekly newsletter.

Famed business-school thinker Clayton Christensen was splendidly profiled in The New Yorker a few weeks back, which set me to reflecting on his influential meditation on K-12 education, Disrupting Class, the 2008 book (co-authored with Michael Horn and Curtis Johnson) that startled the edu-cracy with its bold prediction that half of all high school courses will be delivered online by 2019 and its explanation that technology will produce the “disruptive innovation” in education that previous reform efforts have failed to bring about. As I read the profile, though, I couldn’t help but wonder if the more disruptive force in education is lower-tech and already more widespread than Christensen himself realized.

Disruptive innovation drove out of business organizations in the steel industry that didn't adapt. Photo by hanjeanwat. |

“Disruptive innovation” is his seminal insight, perhaps better summarized in Larissa MacFarquhar’s profile than in the education book itself. “How was it,” he started wondering, “that big, rich companies, admired and emulated by everyone, could one year be at the peak of their power and, just a few years later, be struggling in the middle of the pack or just plain gone?”

He figured it out by closely observing the steel industry. The huge American steel firms (U.S. Steel, Bethlehem, etc.) were challenged and gradually undone by small, nimble producers that Christensen calls “mini mills,” which began by producing low-end products (“rebar”) that the big companies were glad to quit making because they weren’t very profitable anyway. Now bear with this long quote from the profile.

In the world of steel, the “mini mills” were the disruptive innovation that transformed the industry—and put many of the big old firms out of business. (Once-mighty Bethlehem Steel, for example, went bankrupt in 2001.)

Christensen tells similar tales of transistor radios sinking Zenith and RCA, of low-price Toyotas nearly doing the same to GM, Ford, and Chrysler, and many more. The disruptive innovator was able to do things that, at the time, didn’t make sense to the traditional operator—and eventually stole its market.

Back to our K-12 education system. Christensen and colleagues don’t suggest that it’s going out of business but they do say it will be transformed by a pair of disruptive innovations: technology (online learning, in particular) and a shift to “student-centric” learning.

You can already see this starting to happen, if perhaps a bit more slowly than they forecast, and it’s mostly a good thing (though some of today’s online products are shoddy and being used in questionable ways).

But something else is happening, too, that is apt to be just as profound, and it’s something that Christensen sort of pooh-poohed. It’s the emergence of K-12’s own version of mini mills in the form of independent public schools of choice. These could turn out to be as disruptive, and ultimately as devastating, to traditional education systems as those crummy little Sony radios turned out to be to the vacuum-tube behemoths and as Honda was to Detroit. These upstarts may not put the districts out of business but they’re definitely capturing market share and, in some places, hollowing out the enrollments (and revenues) of the “legacy” operators.

Charter schools (5,000-strong and growing) are the most obvious examples but they’re not the whole story. Think, too, of STEM schools. “Outsourced” schools within “portfolio” districts. Parent-trigger schools. The more radical forms of site-managed schools. Technical-vocational schools. Lab schools. Sometimes alternative and magnet schools. The list can be extended.

They’re no longer just one-offs, either. They’re networking—CMOs, EMOs, “recovery school districts,” “chancellor’s districts”—and they’re being systematically replicated by a growing number of organizations, both local and national. A dozen or more cities already find the aggregate enrollment of these education mini mills nearing (or even exceeding) that of the traditional school system. (Think of D.C., New Orleans, Albany, Dayton…)

Independent public schools started with the education system's "rebar." Photo by Christopher Bulle. |

The authors of Disrupting Class were well aware of this phenomenon and saw it as useful but not central to the key innovations they had identified. “As we approached the study of education through the lenses of our research on innovation,” they wrote, “our instinct was to frame chartered schools as disruptive innovations, but upon reflection that was not correct.” Rather, they said, charters are “sustaining” innovations, in that they may do things somewhat differently but “their intent is to do a better job educating the same students that districts educate.”

It’s not clear to me why this disqualified them as disruptive innovators, particularly if they’re successfully invading the markets of traditional providers and capturing more and more customers (and usually doing it at lower cost to the taxpayer, though this also makes their job harder). If, in essence, they’re functioning much as mini mills did within the steel industry.

They have another similarity, too: they started with “rebar,” i.e., mostly with the kids that the traditional providers (education’s “big steel”) weren’t much profiting from—poor and minority kids, hard-to-educate kids, fussy kids, dropouts and would-be dropouts, kids with low scores on state proficiency tests, sometimes youngsters with special needs. And while the districts weren’t exactly glad to see those students leave—they took money with them and eventually cost jobs—they were somewhat relieved, too. In places with fast-growing enrollments, the independent public schools also eased pressure on facilities and capital budgets.

That’s not to say the traditional providers welcomed competition. They (and their employee groups) much preferred quasi-monopolies and almost everywhere did all they could to make life difficult for these new rivals. Sometimes, however, they were shrewd enough to compete back, trying to offer their clients the kinds of programs the innovators were offering, and in a few cases (e.g., Joel Klein’s New York, Tom Boasberg’s Denver) even endeavoring to harness the power of this disruptive model to prod their own systems to do a better job of serving their customers.

Education’s mini mills haven’t always done a great job. Lots of charters, for example, need to improve their services and their products—and, if they do, they will almost certainly go “up-market,” too. The implications for education’s “big steel” could be profound.

A strikingly high number of teachers and principals in the nation’s capital have ditched district schools recently (55 percent of new teachers exit DCPS within two years, compared to one-third nationally), posing a real problem for one of the country’s most innovative school systems. While there’s value in some turnover if the lemons walk out the door, losing more than half of new hires so quickly is excessive. DCPS’s much-lauded approach to human capital must find ways to prioritize retention as much as it does recruitment and evaluation of talent.

A strikingly high number of teachers and principals in the nation’s capital have ditched district schools recently (55 percent of new teachers exit DCPS within two years, compared to one-third nationally), posing a real problem for one of the country’s most innovative school systems. While there’s value in some turnover if the lemons walk out the door, losing more than half of new hires so quickly is excessive. DCPS’s much-lauded approach to human capital must find ways to prioritize retention as much as it does recruitment and evaluation of talent.

Even increasingly diverse communities with appealing magnet schools struggle to integrate their classrooms, the New York Times pointed out on Sunday. Controlled choice and gentrification alone won’t achieve integration: It requires parents willing to take the plunge, and that’s easier said than done.

The D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program will be preserved, following an agreement between Speaker Boehner, Senator Lieberman, and the U.S. Department of Education. The Obama Administration deserves a smidgen of credit for restoring some funding to this important voucher program but mostly a scolding for playing politics with thousands of students’ educations in the first place. The real kudos belongs to Boehner and Lieberman for persisting, even if this victory is incomplete.

While there won’t be any Wisconsin-style redemption for Senate Bill 5 anytime soon, Ohio’s scuttled attempt at collective-bargaining reform is quietly helping districts around the Buckeye State. Spooked by the prospect of diminished bargaining power in future negotiations, a year ago many local teacher unions made pay concessions in return for extending existing contracts, leaving many districts financially stronger than they’d expected to be. It’s a small consolation, to be sure, but a good reminder that even tough losses can turn out to be worth the fight.

Charters rightly get credit for breaking trail when it comes to capturing blended learning’s considerable potential, but another group may soon be joining them: Catholic schools. Case in point, Seton Education Partners paired with a San Francisco parochial school to create innovative blended classrooms and will bring this model to a Seattle school next fall. Traditional districts take note: The competition is ahead on this one.

While it was encouraging to see the U.S. Council of Mayors support parent rights and school choice with its unanimous endorsement of parent-trigger laws last weekend, Gadfly will be even more encouraged when one of these triggers finally succeeds in transforming a school.

READ "How School Districts Can Stretch the School Dollar"

Despite some signs of economic recovery, school districts nationwide continue to struggle mightily. Nobody expects economic growth—or education spending—to rebound to 2008 levels over the next five years, and the long-term outlook isn't much brighter.

In short, the "new normal" of tougher budget times is here to stay for American K-12 education. So how can local officials cope?

In my new policy brief, I argue that the current crunch may actually present an opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of our education system if decision makers keep a few things in mind:

First and foremost, solving our budget crisis shouldn't come at the expense of children. Nor can if come from teachers' sacrifice alone. Depressing teachers' salaries forever isn't a recipe for recruiting bright young people into education—or retaining the excellent teachers we have. Finally, quick fixes aren't a good answer; we need fundamental changes that enhance productivity.

So how can school districts dramatically increase productivity and stretch the school dollar?

One, we should aim for a leaner, more productive, better paid workforce. Let's ask classroom teachers to take on additional responsibility in return for greater pay, eliminate some ancillary positions, and redesign our approach to special education.

Two, we should pay for productivity. A redesigned compensation system would include a more aggressive salary schedule, more pay for more work and better results, and prioritization of salaries over benefits.

Three, we must integrate technology thoughtfully. Online and "blended" school models are coming to K-12 education. They can be catalysts for greater pupil engagement, individualization, and achievement and, if organized right, they can also be opportunities for cost-cutting.

Many districts continue to face budget challenges of historic proportions. Rather than slashing budgets in ways that erode schooling, let's rethink who we hire, what they do, how we pay them, and how to incorporate technology—that's where the big payoff is.

READ "How School Districts Can Stretch the School Dollar"

Despite some signs of economic recovery, school districts nationwide continue to struggle mightily. Nobody expects economic growth—or education spending—to rebound to 2008 levels over the next five years, and the long-term outlook isn't much brighter.

In short, the "new normal" of tougher budget times is here to stay for American K-12 education. So how can local officials cope?

In my new policy brief, I argue that the current crunch may actually present an opportunity to increase the efficiency and productivity of our education system if decision makers keep a few things in mind:

First and foremost, solving our budget crisis shouldn't come at the expense of children. Nor can if come from teachers' sacrifice alone. Depressing teachers' salaries forever isn't a recipe for recruiting bright young people into education—or retaining the excellent teachers we have. Finally, quick fixes aren't a good answer; we need fundamental changes that enhance productivity.

So how can school districts dramatically increase productivity and stretch the school dollar?

One, we should aim for a leaner, more productive, better paid workforce. Let's ask classroom teachers to take on additional responsibility in return for greater pay, eliminate some ancillary positions, and redesign our approach to special education.

Two, we should pay for productivity. A redesigned compensation system would include a more aggressive salary schedule, more pay for more work and better results, and prioritization of salaries over benefits.

Three, we must integrate technology thoughtfully. Online and "blended" school models are coming to K-12 education. They can be catalysts for greater pupil engagement, individualization, and achievement and, if organized right, they can also be opportunities for cost-cutting.

Many districts continue to face budget challenges of historic proportions. Rather than slashing budgets in ways that erode schooling, let's rethink who we hire, what they do, how we pay them, and how to incorporate technology—that's where the big payoff is.

For almost five years now, the Center for Reinventing Public Education and Mathematica have teamed up to assess the effectiveness of charter-management organizations (CMOs). And a productive partnership it has been. Their latest report on this topic (the fifth, by Gadfly’s count) deserves attention. It focuses on how CMOs hire, train, and manage staff to maximize their schools’ instructional and cultural coherence; there are strong implications here for districts and other charters. Analysts found that successful CMOs managed talent in three key ways. First, they recruited and hired carefully, targeting pipelines like Teach For America and communicating clearly the school’s mission and work ethic. (Messaging, these CMOs believe, helps teachers self-select during the application process.) Second, they used intensive and ongoing socialization of team members, including routine observations and real-time feedback. Third, they aligned pay and promotion to organizational goals, meaning, for example, that stellar teachers were offered the chance to coach others, develop new programs at the schools, and more. CMOs also provided cash rewards to rock-star teachers which, interestingly, were based more on leaders’ professional opinions than assessments or performance metrics. The report draws a number of conclusions that district schools and other charters would be wise to follow insofar as they can.

SOURCE: Michael DeArmond, Betheny Gross, Melissa Bowen, Allison Demeritt, and Robin Lake, Managing Talent for School Coherence: Learning from Charter Management Organizations (Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, June 2012).

We’ve long rued the state of American science education—and crammed worrisome evidence from national and international assessments (as well as our own evaluations of states’ science standards) into the ears of all who will listen. This follow-up report to the 2009 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) science test has us concerned all over again, both with what it says and with how its findings may be interpreted. It examines (for the first time) students’ ability to perform hands-on and interactive computer-based science tasks. Three key trends emerged: The majority of pupils could make straightforward observations of data (e.g., 75 percent of twelfth graders could test a water sample and note whether it met EPA standards). Yet they struggled when investigations contained multiple variables or required strategic decision making to gather appropriate data (e.g., just 24 percent of eighth graders could manipulate metal bars to determine which were magnets). Finally, though students could often arrive at the correct conclusion, they struggled to provide evidence for their answer. (Seventy-one percent of fourth graders could accurately choose how volume changes when ice melts into water but only 15 percent could explain why that happened using evidence from the experiment.) These stumbles have already elicited grumbles among reporters, government officials, and others. Their argument: These data are proof that we’re forcing too much content (presented via rote memorization), which is hindering students’ ability to reason. But, as esteemed biologist Paul Gross wrote earlier this week, “there is no reasoning, scientific or otherwise, in the absence of knowledge.” Yes, hands-on activities are a critical component of science education. But so is learning the content. Thankfully, the NAEP activities are designed to measure content knowledge, too.

We’ve long rued the state of American science education—and crammed worrisome evidence from national and international assessments (as well as our own evaluations of states’ science standards) into the ears of all who will listen. This follow-up report to the 2009 National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) science test has us concerned all over again, both with what it says and with how its findings may be interpreted. It examines (for the first time) students’ ability to perform hands-on and interactive computer-based science tasks. Three key trends emerged: The majority of pupils could make straightforward observations of data (e.g., 75 percent of twelfth graders could test a water sample and note whether it met EPA standards). Yet they struggled when investigations contained multiple variables or required strategic decision making to gather appropriate data (e.g., just 24 percent of eighth graders could manipulate metal bars to determine which were magnets). Finally, though students could often arrive at the correct conclusion, they struggled to provide evidence for their answer. (Seventy-one percent of fourth graders could accurately choose how volume changes when ice melts into water but only 15 percent could explain why that happened using evidence from the experiment.) These stumbles have already elicited grumbles among reporters, government officials, and others. Their argument: These data are proof that we’re forcing too much content (presented via rote memorization), which is hindering students’ ability to reason. But, as esteemed biologist Paul Gross wrote earlier this week, “there is no reasoning, scientific or otherwise, in the absence of knowledge.” Yes, hands-on activities are a critical component of science education. But so is learning the content. Thankfully, the NAEP activities are designed to measure content knowledge, too.

SOURCE: National Center for Education Statistics, The Nation’s Report Card: Science in Action: Hands-On and Interactive Computer Tasks from the 2009 Science Assessment (Washington, D.C.: Institute of Education Sciences, June 2012).

Baking a successful school-choice soufflé is challenging. The ingredients are hard to come by: Schools must be high performing while simultaneously offering options to a diverse parent base. And the recipe is fussy: Navigating the system should be easy and fair. There can be no inherent incentives to game the system. Denver’s new school-choice program (creatively titled SchoolChoice) may not be “Iron Chef” quality, but it has some stimulating flavors cooked in. This encouraging report from A+ Denver explains: Last year, the Denver Public Schools (DPS) streamlined its choice program, merging all sixty of the district’s varying school applications and deadlines into one system. This alleviated much headache and caused an uptick in intradistrict choice. For the 2010-11 school year, over 22,700 students (comprising a little over 25 percent of all pupils) participated, with over two-thirds of them gaining access to their top-choice schools (and 83 percent to one of their top three choices). Even more promising, demand for a school was highly correlated with its quality. Improvements to the program can still be made, however. The report finds, for example, that poor and minority families choose schools that are generally lower performing than their better-off peers (likely due to school location and marketing). There’s lots to learn from the paper, including new insights about parental preferences and school-choice decision-making. As DPS refines its program—and as other districts seek to copy, and improve upon, its recipe—this report will offer helpful guidance.

SOURCE: Mary Klute, Evaluation of Denver’s SchoolChoice Process for the 2011-2012 School Year (Denver, CO: University of Colorado, prepared for the A+ Denver SchoolChoice Transparency Committee, June 2012).