As our country grapples with racial injustice, there are persistent calls to diversify elite institutions at all levels, from corporate and foundation boards to law schools and medical schools to undergraduate programs. All good. And in line with the adage that college begins in kindergarten, many of these efforts eventually look at schools to better prepare more Black, Hispanic, and low-income children to excel academically and earn a shot at entering selective universities. To do that, we need to make sure that the most promising among them get enrichment and acceleration. That means gifted education.

Yet tragically, instead of following that logic and expanding gifted services for Black, Brown, and other historically disadvantaged students, some insist that the anti-racist thing to do is eliminate them. This has led to misguided questions like “Is it even possible to make a concept that has racist origins more equitable?” in an essay published by the Hechinger Report, and moves that seek to replace gifted ed with toothless initiatives like “schoolwide enrichment.” This is exactly the wrong approach.

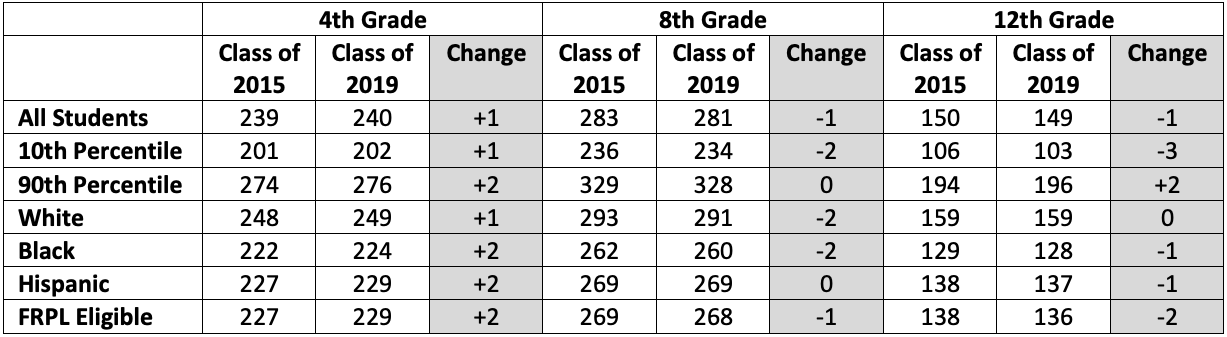

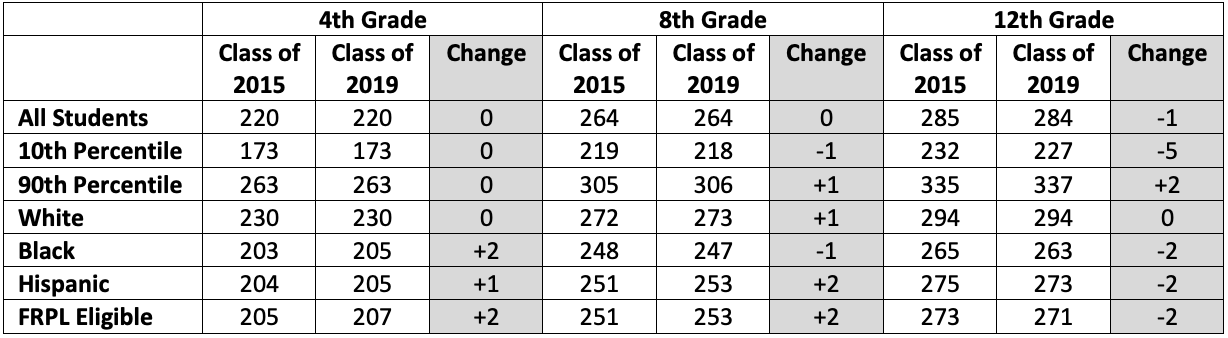

To be sure, gifted education has a diversity problem, due in part to how school systems have historically designed these programs and other enrichment efforts. A Fordham study in 2018 called Is There A Gifted Gap? found that White students constitute 47.9 percent of the student population but 55.2 percent of those enrolled in gifted programs, while the comparable figures for Black students are 15.0 and 10.0 percent, and for Hispanic students, 27.6 and 20.8 percent. Those latter student groups are also 49 and 23 percent less likely, respectively, to participate in Advanced Placement than their peers. And when Black and Brown students attend a school that offers International Baccalaureate courses, they are 62 percent and 51 percent less likely, respectively, to take part.

But the problem isn’t the idea of gifted education itself—which, far from being inherently racist, is simply the practice of grouping higher-achieving and higher-potential students together so that they can benefit from deeper and faster curricula that wouldn’t work well in regular classrooms, especially classrooms with lots of students struggling to reach grade level.

The real problem has three components. First, our country, communities, and schools have long done a poor job of maximizing the potential of students in low-income neighborhoods that are predominantly Black and Hispanic—regardless of their ability. Not only do they suffer from poverty, they have less access to healthcare, healthy food, safe streets, early childhood education, and much more. And then when they do attend school, it’s too often in crumbling buildings that lack adequate supplies, where they sit in crowded and unruly classrooms with less experienced teachers who are more likely to transfer or quit. The list of disadvantages goes on. But the takeaway is simple: We make it far too difficult for these children to succeed.

Second, too many districts serving poor students and students of color have taken previous and misguided charges of racism to heart and eliminated their own gifted education programs, opting instead for the lure of “heterogeneous classrooms.” This jargon is based on the egalitarian but mistaken notion that letting some kids go faster than others, even go at their own speed, is inherently suspect. But here’s the thing: Proponents of this fallacious view have long been more effective at shaming urban districts in deep-blue cities to eliminate gifted education than they have been with their affluent and suburban counterparts. So rich kids with lots of academic potential still get access to enrichment and acceleration—in their fancy suburban public schools, expensive private schools, or at home—whereas poor and minority kids in the city do not.

Third, even when school systems do offer gifted programs, they are often too small and limited to serve all students who might benefit from them, especially Black, Hispanic, and low-income children. Often such programs are concentrated in neighborhoods full of demanding upper-middle class parents. In many places, moreover, admissions are based on standardized test scores, for which administrators set objective cutoffs—ironically, in the name of equity. These tests are rarely universal, meaning families have to ask even to take them, or must rely on teachers to nominate their children as candidates. This ends up favoring affluent and advantaged children, who tend to score higher on standardized tests because of those advantages—not because they’re more able or have more potential. Higher-income students are also more likely to have engaged, pushy parents, who are more likely to know about the tests, make sure their kids take them, do everything they can to motivate educators to pick their children when that’s required, and sometimes engage private tutors to give their kids an academic boost.

These problems—systemic, and in some cases systematically racist, to be sure—have nothing to do with the basic idea of gifted education. The idea remains sound and stands to benefit the Black, Brown, and low-income children who need it most. We just have to expand access, while ensuring that these programs continue to challenge all of their students and maximize their potential.

To achieve this, districts should adopt systems that better develop the natural ability of all high achievers, and then more equitably identify them for gifted services. First, they should “frontload,” meaning they ought to raise schools’ academic rigor in early grades so that disadvantaged pupils are ready for more advanced offerings later. Then they should universally test all students beginning in third grade for gifted program eligibility, when the excellence gap has hopefully narrowed because of the frontloading in pre-K and K–2. The top 5 percent or so of test takers in each school, not the top 5 percent in the district, should be identified for gifted ed. Joining them should be another 5 percent of pupils nominated by teachers on the basis of uncommon potential or simply a gleam in the eye.

This would diversify the population qualifying for these services and not just favor kids who are White, Asian, or upper-middle-class, as the system does today. And in giving high-ability and high-potential Black and Hispanic students so many more years of increased academic rigor and enrichment, it would better prepare them to gain acceptance to, and excel at, selective high schools and colleges, where they’d earn degrees that make them competitive for respected and lucrative careers. In other words, it achieves the ends of diversifying opportunities for Black, Brown, and low-income children, but does so by building up their achievement, instead of tearing down the unique and valuable services provided by high-quality gifted programs.

As calls increase to eliminate gifted programs in the name of equity, policymakers and school leaders must resist them—and recognize that bowing to that misguided pressure will do more harm, not less, to their Black and Brown students. Instead, they should double down on gifted education, diversifying and strengthening it so as to maximize its benefits for the disadvantaged boys and girls that need it most.