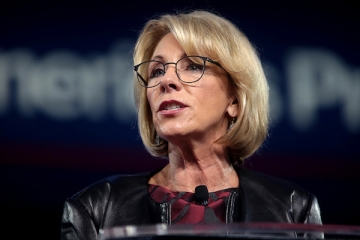

Advice for Secretary DeVos from five public relations professionals

By Michael J. Petrilli

By Michael J. Petrilli

Few people would disagree that Secretary DeVos's tenure is off to a rocky start. Much of this is not her fault; working for President Trump is proving to be a challenge for just about everyone, all the more so in a field where he is so widely despised. Some sort of restart is clearly needed.

To get ideas about what that might look like, I reached out to five friends, all of them public relations professionals who work in education. They have served Democrats and Republicans, previous Administrations, and officials at the local, state, and federal levels. Here are their thoughts. We’ll start with a few who asked to stay off the record.

Anonymous #1

I’d suggest a couple of things:

Anonymous #2

Secretary DeVos needs serious, intense media and presentation training. She is not ready for prime time and as such is prone to what I would call "brain freeze." She has never been in the spotlight, and so she went from philanthropist to a serious politician overnight with no real training. In order to gain the confidence she needs, I recommend lots of dry runs with professional feedback and time spent with experts in the field who do not have a vested interest in her decisions, but who have the history and perspective she needs to hear in order to trade in her taking points for real understanding.

Jason Smith, Managing Partner, Widmeyer Communications, a Finn Partners Co.

One thing I know from twenty years of education communications: My PR tools can’t fix your policy problem. Secretary DeVos’s challenges with a number of constituencies—the civil rights community, teacher unions, or reformers who aren’t hypnotized by the allure of vouchers—aren’t the result of a messaging gaffe. The bear jokes were entertaining, but that’s not her problem. Her problem is the public’s perfectly logical reaction to her policy point of view. If the secretary wants to elicit more positive responses from the public that pays attention to schools, she will need to revisit her policy platform: a full-throated endorsement of the principle of public schools, a clear understanding of the nuance and research around choice, and a renewed emphasis on universal accountability measures that can’t be gamed by state or local leaders.

Patrick Riccards, aka Eduflack, Chief Communications and Strategy Officer, Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation

First, offer a strategy. A budget is not a strategy. In the absence of knowing what Secretary DeVos intends to do, we are all making assumptions based on the budget. School choice is but a piece of that strategy. Without it, DeVos's opponents are driving the narrative.

Second, staff up. It's been three months since her confirmation. We still don't have a nominee for under secretary, deputy secretary, or assistant secretaries for those areas we most care about.

And third, get out of the bubble. DeVos's speech at Bethune-Cookman was an important step in this regard. She owns the bully pulpit. Use it. And use if for more than friends like charter schools or GSV-ASU. Go to ISTE next month to talk innovation and ed tech, just as she did at GSV. Talk higher ed and student loans at SHEEO in July. Go to NGA to talk to the governors about ESSA implementation. If one is particularly bold, ask for a speaking slot at AFT. Use it to emphasize the areas of agreement and the value of meaningful disagreement.

Right now, the Department of Education simply isn't engaging in public engagement. It isn't that they aren't good at it, it's that they aren't doing it at all. Stop playing only defense. Stop letting opponents define the terms of engagement. Stop retreating. Use the bully pulpit. Speak on important issues like career and technical education, community colleges, and early childhood education. Expand the reform discussion to include teacher prep and higher education accountability. Use the one hundred days of summer to prepare a bold plan for improving education, to be launched at the start of the school year.

Peter Cunningham, Education Post

In a phrase I would say, “Swim where the water is warm for now.”

First—general advice:

And now a few action steps:

Despite the recent repeal of federal guidelines for states’ compliance with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), states are steadily submitting their proposals, and they are rightfully receiving some attention. The policies in these proposals will have far-reaching consequences for the future of school accountability (among many other types of policies), as well as, of course, for educators and students in U.S. public schools.

There are plenty of positive signs in these proposals, which are indicative of progress in the role of proper measurement in school accountability policy. It is important to recognize this progress, but impossible not to see that ESSA perpetuates long-standing measurement problems that were institutionalized under No Child Left Behind (NCLB). These issues, particularly the ongoing failure to distinguish between student and school performance, continue to dominate accountability policy to this day. Part of the confusion stems from the fact that school and student performance are not independent of each other. For example, a test score by itself gauges student performance, but it also reflects, at least in part, school effectiveness (i.e., the score might have been higher or lower had the student attended a different school).

Both student and school performance measures have an important role to play in accountability, but distinguishing between them is crucial. States’ ESSA proposals make the distinction in some respects but not in others. The result may end up being accountability systems that, while better than those under NCLB, are still severely hampered by improper inference and misaligned incentives. Let’s take a look at some of the key areas where we find these issues manifested.

Status versus growth

ESSA grants states the flexibility to include growth measures in their school rating/dashboard systems. This is a major sign of progress in accountability measurement. Status measures (how highly students score on tests, measured by average scores or proficiency rates) are mostly a function of student background. On the other hand, how far students progress while attending schools can tell us about schools’ actual effectiveness (at least in raising test scores). That is, status measures primarily gauge student performance, whereas growth measures are best classified as school performance indicators.

If I were designing an accountability system, I would use both, but for different purposes. Status measures can help determine which schools are serving students most in need of catching up, and resources can be directed to those schools. Growth model estimates, on the other hand, can identify schools that are (and are not) serving their students well, and target interventions accordingly, perhaps prioritizing schools with students that are most in need of help.

Among those states planning to calculate school ratings, the current trend is some roughly equal weighting of status and growth (along with subgroup-specific and a few additional measures). This seems to reflect a mindset of “mixing different things together to get a comprehensive rating.” This is a bit misguided, as the components of this system aren’t all equipped to measure the same underlying dimension. Mixing status and growth into a school performance measure is like rating the efficacy of health and fitness programs by mixing participants’ current weight and the weight they have lost. The former tells you something about people’s health, the latter about whether the program helped them lose weight. Both are important, but you probably wouldn’t combine them to evaluate the programs.

Again, this is better than the NCLB-style system, which was based almost entirely on status. Nevertheless, to the extent status is included in a single rating system, schools will continue to be rewarded or penalized based on the students they serve, and not how well they serve them (see this recent article for more on this).

One can, for example, only cringe at the reaction of a highly effective inner city school, where students make tremendous progress every year, receiving a low rating simply because their students enter so far behind. This school would be ignored or perhaps even punished when it should be celebrated and copied.

Another big problem here is high schools. Since many high schools serve only one or two tested grades, and many others serve none at all, ratings systems for these schools tend to rely on measures such as graduation rates, which are status measures with the same implications as proficiency rates or average scores. From this perspective, whatever progress there has been in accountability measurement under ESSA will not accrue as much to high schools, the ratings of which will continue to be driven almost entirely by which students they serve.

Achievement gaps and “gap closing”

States also have the option of choosing achievement gap or “gap closing” measures, which measure the size of differences in achievement between subgroups (e.g., racial and ethnic groups), or progress in narrowing these discrepancies, respectively. This is very important information and should be reported. However, in the context of high stakes accountability systems, there is a strong case against the use of these measures, which I will not repeat here. For our purposes, suffice it to say that gaps don’t really tell you anything about the performance of schools, and changes in the gaps can and often do occur for undesirable reasons (e.g., both subgroups decline, but one faster than the other).

So, while achievement gaps are enormously important, and must be monitored constantly, they are in their simplest form not well-suited to play a direct role in high stakes accountability systems. Moreover, there are alternatives. One example would be growth model estimates for subgroups, such as low-scoring students. This would serve the same purpose as crude “gap closing” measures, but do so in a manner that gauges actual school performance (though it is not clear how much schools’ overall effectiveness varies from their effectiveness with subgroups, nor why such variation would occur).

Achievement targets

Perhaps the most well-known provision of NCLB was the “requirement” that most schools exhibit 100 percent proficiency within ten or so years. ESSA allows states to choose their own targets, overall, and by subgroup. This is a good thing, at least in theory, even though states that attempt to set realistic goals—those that reflect the fact that real progress is slow and sustained—will likely incur political costs, such as accusations of “low expectations” and “lowering the bar.”

In any case, the problem here is that achievement targets, like proficiency rates and average scores, fail to account for the fact that schools serving higher-achieving students will meet their targets far more easily, whereas other schools will have enormous difficulty doing so. Once again, the information pertains to the students a school serves, not the school’s effectiveness.

Note also that whether or not schools meet achievement targets seems like a growth measure, but it is not. It does not necessarily indicate whether students in a given state, district, or school are making progress. Since students enter and exit the sample every year (those at the lowest and highest tested grades, respectively), year-to-year changes compare different groups of students. Even over the long term, average scores and rates can be flat or decrease even when students are making progress (see the illustration here).

Imagine a middle school that, every year, enrolls a new cohort of seventh graders who are, on average, a year or two behind proficiency (to say nothing of losing a cohort of ninth graders who had been making progress for three years). This school could work miracles and still fail to meet targets. There is a lot to be said for setting goals, and for setting them high. But you can’t really gauge how far you should go if you don’t pay attention to where you started.

Non-test measures.

The ESSA requirement that states include some kind of performance measure that does not rely on state tests is a good example of a policy that enjoys wide agreement on the ends but not the means. In short, everyone agrees that non-test measures are a priority, but there are massive questions about what they should be (this issue deserves a separate post, or more likely, a book). The reality is that this ESSA provision basically represents a requirement for field testing, but potentially high stakes field testing.

Moreover, the student versus school performance distinction is not just important when it comes to test scores. For example, thus far, many states are opting to fulfill the non-test measure requirement with absenteeism/attendance. By themselves, these are also just status measures (i.e., they tell you more about the students a school serves, rather than how well they serve those students). School “climate” surveys are also a possibility, but they too may vary systematically, in part, by observed and unobserved factors outside of schools’ control.

There are no easy answers here, and non-test indicators are still something of a measurement frontier. But adopting non-test measures won’t be much of an accomplishment if we use them in the same misguided way we’ve been using test-based measures.

***

Perfect measurement is not necessarily a requirement for accountability policies to have some positive impact (NCLB being a perfect example). And designing these systems is very difficult. Even if there was a strong consensus on the “correct” measures and how to use them, which most certainly is not the case, measurement issues are far from the only factors at hand. There is plenty of politics in policymaking.

That said, while ESSA is an improvement in terms of accountability measurement, and that should not be dismissed or downplayed, it is still a long way from where we need to be. In many respects, there are a lot more repeated than corrected mistakes.

The purpose of accountability policies is to change behavior productively, and measurement and incentives must be aligned to produce these behavioral changes. This is much harder when measures are misinterpreted.

Matthew Di Carlo is a senior research fellow at the Albert Shanker Institute.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in the Shanker Blog.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Editor's note: This is the third essay of a three-part series (parts one and two can be found here) that examines the major challenges facing education reformers. The author adapted these essays from his keynote address at the Yale School of Management’s Education Leadership Conference in April.

In previous columns, I wrote about the political and policy problems we face as people fighting for change in the education space. But that’s only part of what ails our reform effort.

We also have a partisan problem.

This may be the one that’s easiest to see—though it is perhaps toughest to fix—and it spilled out into the street in the wake of Hillary Clinton’s presidential defeat. It now charges the national debate, around all policy, with a third-rail-like electricity on both sides of the aisle.

Party allegiance is the new litmus test not just for political philosophy, but for personal belief and social inclusion. Answering the wrong way on the wrong question not just on reform—but on anything—carries the weight of possible ostracism from both the left and the right. My own lens on this is through the tribe of Democrats, because those are the primaries in which I vote and the affiliation of most of the folks who are close to me. Folks I admire and from whom I seek counsel and direction during difficult times.

I understand it. I found the last presidential campaign distasteful. I rejected the division and the acrimony that typified the exchange, particularly where race was concerned. I tell folks sometimes that black lives matter—and that since I have one, it matters a whole lot to me—but the electoral process left me confused about whether our leaders actually agree with me. I ultimately supported Clinton despite my firm belief that she would appoint a secretary of education determined to make our lives harder, not easier. In the professional sense, I voted against my own interests because I thought it might be best for America.

But I also spend a lot of time traveling the country, which means, unlike many of my peers, I am not confined to either of the progressive coasts. At 50CAN, four of the five states I manage—Tennessee, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Georgia—are politically a deep crimson.

Despite their red hue, one thing doesn’t change as I move between them: how desperately children need great schools to ensure they reach their full potential. And though these states also bring the problems of rural education to the forefront, there are plenty of black and brown kids in cities who need our help as badly as any kid in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn, does. Blue state or red state, our kids need all the help they can get, and they need it from everyone.

This is why I find the advance—or the retreat, depending on your view—by so many of my reform brothers and sisters to their respective hard rights and lefts not only troubling, but counterintuitive. And, in the long term, destructive.

It’s a pivot of safety, tribalism, and sameness, one of ease and elitism when our children need us to behave in precisely the opposite fashion, running toward one another instead of away.

We don’t have an education reform movement because liberal Democrats believe in civil rights. And we don’t have one because conservative Republicans believe in market solutions, low regulation, and freedom. We have one because they could believe in them both, at the same time, together, and at the same table. The golden age of “reform” that folks associate with President Barack Obama exists only because of a history of this sort of collaboration.

It flowered when President Bill Clinton and a Republican Congress came together on charters. It grew further with President George W. Bush and the late Sen. Ted Kennedy, who together built and passed the No Child Left Behind Act. It expanded charters in places like Newark, where Republican Gov. Chris Christie and Democratic Mayor Cory Booker somehow managed to work together to make change.

Republican Gov. George Pataki, with the help of Democratic Rep. Floyd Flake, passed New York’s charter school law in 1998. Democratic Assemblywoman Polly Williams and Republican Gov. Tommy Thompson joined to create the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, the country’s first.

Without a willingness to look past party with an eye toward the goal of improving education for our children, none of this would have been possible.

Much of what I read and see now seems ignorant of this history. And not just ignorant of it—dismissive, detached, and arrogant to it. There isn’t a progressive state where a teacher evaluation framework, tenure reform law, equitable funding formula, charter, or choice program passed without the support of both Democrats and Republicans. A retreat from the political realities of what it takes to make change—real change, not just the kind that makes partisans happy, but the kind that actually alters culture in a way that unmakes what is broken so something better can be created—isn’t just selfish, it’s self-interested. And it ignores the most important of factors: that change of this kind, and of this scale, can’t be done alone.

We don’t need new edges; we need a new center. So consider this: If your partisan values are more important to you than your education reform values, perhaps you should ask yourself if you are in the right place, at the right time, doing the thing that is best for you and your beliefs.

I happen to be an ed reformer first—my moral and professional compasses point in the same direction, and I act in a fashion that is aligned around changing policy for kids. This is also to say I am a Democrat second, and being one informs my view on reform—particularly on issues of equity—but is in service to that view. Not everyone sees the world this way. In fact, many people I know well don’t see it this way at all. So if you’re a Democrat first, or a Republican first, or a partisan first, and that is what matters most to you, I support that fully. The country is a mess right now, and we need political reform as much as we need education reform.

But it’s also possible that, if you feel that way, the Democratic National Committee or the Republican National Committee would benefit more from your decision-making right now than a boy on a corner in Bridgeport who just needs you to be on one side—and that side is his. He’s actually the last person who needs you to be a partisan—steeped in what you won’t do and closing off policy opportunities that make you uncomfortable because of your political beliefs—because in the end, it’s his life, not yours, that depends on it.

We should all see the world through his eyes when thinking about this.

I encourage everyone to reflect on the life of Martin Luther King Jr. and his efforts to pass the Civil Rights Act when thinking about our partisan problem. King worked with many people to pass the act. Some of those people were racists. And the most notable of them might have been President Lyndon Baines Johnson himself. Johnson’s biographer Robert Caro described him as a connoisseur of the word “nigger” who tailored its use and inflection to the home regions of members of Congress. As Obama noted in 2014, “During his first twenty years in Congress, he opposed every civil rights bill that came up for a vote, once calling the push for federal legislation a farce and a shame.”

The lesson here isn’t necessarily about Johnson’s motivations, or even the sincerity or veracity of the change he underwent that made him a supporter of civil rights. It is instead about King’s single-minded focus on the goal of equality for black people, and the relentless pursuit of that goal through political disconcert and social pressure. And in this case, it included his willingness to work with a man—one fluent, skilled, and practiced in the casual use of the greatest insult to black people—who offered him not comfort, but the chance to improve the lives of those very same people. The history of minorities seizing power in America has always been colored by these crushing concessions. King’s discomfort, I think, is of the sort we have to live with now if we want to make progress in these difficult political times.

Education reform isn’t about how you may or may not feel at cocktail parties or your own political or personal proclivities. It is about kids dying civic and physical deaths in schools that don’t work for them. Progress, real progress, never feels good. And it’s always uncomfortable, because change is uncomfortable, even when it’s for the better.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in The 74.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

On this week's podcast, special guest Dr. Constance Lindsay, a research associate at the Urban Institute, joins Mike Petrilli and Chester Finn to discuss the positive effects of teachers of color on students of color. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines whether school choice increases parental demand for information about school quality.

Michael F. Lovenheim and Patrick Walsh, “Does Choice Increase Information? Evidence from Online School Search Behavior,” NBER (May 2017).

A new report seeks to probe the impact of state takeovers of entire low performing districts—which don’t occur often and therefore have a limited evidence base. Analysts examined the results of one such takeover in Lawrence, Massachusetts, a midsized industrial city thirty miles north of Boston that is rife with deep poverty and whose primary school district includes roughly 80 percent of students who are English language learners.

The district enrolled approximately 13,000 students in twenty-eight schools in fall 2011, when the Massachusetts Board of Elementary and Secondary Education classified Lawrence Public Schools (LPS) as a “level 5” district, the lowest rating in the state’s accountability system, and placed it into receivership. The receiver, a former Boston Public Schools deputy superintendent, took over in 2012 and was granted broad discretion to—inter alia—alter the teachers’ collective bargaining agreement, require staff to reapply for their positions, and extend the school day or year.

The turnaround strategy had five major components: 1) setting ambitious performance targets; 2) increasing school autonomy by reducing spending on the central office by $6.6 million in the first two years, pushing funds down to the school level, and providing different levels of autonomy and support based on each school’s prior performance and capacity; 3) staffing changes, which led to more than half the principals being replaced in two years and the lowest performing teachers also being let go (8 percent were removed or fired, but resignations and retirements brought that to one third being replaced, many by Teach For America corps members); 4) teaching teachers how to use data to drive instruction; and 5) increasing learning time via things like “Acceleration Academies,” which are intense, small-group tutoring programs offered during winter and spring breaks, with student participants selected by their principals, and outstanding teachers deployed (from within and beyond Lawrence) through a competitive process.

Analysts examine impacts in the first two years of the turnaround. They use as a comparison group student level data from across the state for 2006 to 2015, focusing most of their analysis on one fourth of those students who attend the poorest districts. They examine changes over time in individual students, seeking trends before and after the turnaround and comparing LPS to demographically similar districts not subject to turnaround. They find sizable impacts on math achievement; for instance, by year two, the turnaround had improved LPS math scores by 0.29 standard deviations when compared with kindred districts. Yet the ELA impact ranged only from 0.02–0.07 SD. English language learners saw particularly large gains in math in both years, as well as moderate ELA gains. The gains were more pronounced in the elementary and middle schools, less so in high school.

Though a selection effect is obviously present in the Acceleration Academies, their most rigorous analytic models nonetheless suggest that these weeklong tutoring sessions were an important factor in the turnaround’s success. Yet analysts found scant evidence that the turnaround affected other outcomes like attendance or the probabilities of (a) remaining in the same district, (b) staying in school, and (c) graduating in twelfth grade, compared to comparison districts.

Three quick takeaways: these are fairly encouraging results for a state turnaround, so we’ll be curious to see if they persist beyond the first two years; ditto on whether similar success can be replicated elsewhere (made more likely if states take on one district turnaround and not multiple); finally, the positive evidence continues to mount (here, here, and here, too) that individual or small-group tutoring is advantageous for struggling students, so let’s continue to find ways to bring it to scale.

SOURCE: Beth E. Schueler et al., “Can states take over and turn around school districts? Evidence from Lawrence, Massachusetts,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (January 2017).

This study uses the attendance records of over 50,000 middle and high school students in a major California school district to gauge the prevalence of “part-day absenteeism”—how often students miss some of the school day but not all of it.

Overall, the authors find that part-day absenteeism is responsible for at least as many missed classes as full-day absenteeism, and that the inclusion of part-day absences raises the chronic absenteeism rate from 9 percent to 24 percent for students in grades six through twelve. On average, students in these grades were absent for all of 4.2 percent of school days and part of 12.2 percent of school days. However, while almost half of full-day absences were excused, 92 percent of part-day absences were unexcused.

Interestingly, although both full- and part-day absenteeism show a jump at the transition from middle school to high school, full-day absenteeism declines from that point onward while part-day absenteeism remains elevated in grades ten and eleven before increasing again in grade twelve. Across all grades, absenteeism varies considerably by time of day. For example, the absenteeism rate for the first and last periods of the day is around 5 percent, while the absenteeism rate for third period is around 3 percent. In addition to these differences, students are somewhat more likely to be absent from some subjects than others. Specifically, they are most likely to be absent from their PE class, followed by their foreign language class, math class, science class, ELA class, and social studies class (in that order). However, these differences are modest, meaning students miss almost as many core classes as they do PE classes.

Unsurprisingly, Asian students have a lower part-day class absence rate (2.6 percent) than white students (3.8 percent), Hispanic students (6.1 percent), or African American students (8.3 percent). Furthermore, incorporating part-day absences sharply increases the overall chronic absenteeism gap between underrepresented minority students and their non-minority peers. For example, when part-day absences are included the chronic absenteeism rate increases in is 47.7 percent in twelfth grade and 69.9 percent for black students. Chronic absence rates are also higher among English learner students (29 percent) than among non–English learners (23 percent), and far higher among students with special education status (46 percent) than among other students (24 percent).

Because students miss the first class of the day more than any other, the authors suggest scheduling planning periods for core-subject teachers during first period to increase attendance in these key classes, in addition to “targeting part-day absence reduction efforts to meet the needs of underrepresented minority students.” Given the huge number of states that are moving to incorporate chronic absenteeism indicators into their accountability systems, one component of this effort should surely be a closer examination of states’ existing data capabilities, as well as their definitions of “chronic absenteeism.”

SOURCE: Camille Whitney and Jing Liu, “What we’re missing: A descriptive analysis of part-day absenteeism in secondary school,” AERA Open (April 2017).

A short new report by A+ Colorado evaluates the recent gains of Denver Public Schools (DPS) in a way that education leaders elsewhere might beneficially heed.

First, we see that more DPS students met grade level proficiency for Math and ELA in 2016 than in 2015. Then the authors list the highest achieving schools, as well as those schools that made the biggest jumps in proficiency rates. A scatter plot shows a demographic index and elementary school ELA proficiency rates. Here the serious thinking begins.

We see that a large number of DPS schools are besting their peers around the state with comparable demographics. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re doing great. For example, Knapp Elementary, a district-run school, had fewer than 35 percent of its students read and write at grade level, yet it’s far above the state average for schools with similar concentrations of poor and multilingual students. Knapp also makes the podium when the authors rank schools by growth rates.

The authors conclude by showing the rate at which Denver needs to improve to meet its 2020 goals, and we see how much heavy lifting lies ahead. From 2015 to 2016, DPS increased the number of third graders proficient in ELA by +3 percentage points, but it would have to improve by +12 percentage points per year from here on out to get to where it says it wants to be in 2020. Faced with that kind of challenge, some might give up on the goal. Others might dig into the data and find the best ways to move forward. For those who plan to keep improving, this report is a great place to start.

SOURCE: “Start with the Facts: Denver Public Schools,” A+ Colorado (May 2017).