Betsy DeVos's real record in Michigan

By Daniel L. Quisenberry

The announcement that Betsy DeVos would be the President-elect’s nominee for U.S. Secretary of Education has touched off more speculation than the College Football Playoffs. But at least in football, expert opinions are usually grounded in facts. For the incoming secretary, opinion and commentary have mostly taken place in a reality that is, as Einstein once said, “merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one.”

Indicative of this trend is the falsehood that Michigan charters have no regulation, no oversight, and no accountability. Critics who employ this fiction often roll it into the fallacy that, because Betsy is influential in the state, those mistaken characteristics will soon be national objectives. This defective perception of Michigan tells you nothing of the potential DeVos agenda. To do so is to use the logic of Monty Python: If wood floats and a duck floats, a duck must be made of wood.

In truth, DeVos and the organizations she has supported have played a positive role in shaping Michigan’s charter sector—which is quite strong. Indeed, it took the bronze in a recent report from the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools that looked at real outcomes of charter quality, growth, and innovation across eighteen states. And just this week it took a “most improved” prize in a report card from the National Association of Charter School Authorizers.

Most importantly, Michigan’s charter schools have achieved strong student academic results, as demonstrated in CREDO’s National Charter School Study 2013. As CREDO’s director, Dr. Margaret Raymond, put it:

These findings show that Michigan has set policies and practices for charter schools and their authorizers to produce consistent high quality across the state. The findings are especially welcome for students in communities that face significant education challenges.

Nevertheless, the sector has strived to improve further—and to that end, it supported efforts in this spring’s legislative session to strengthen accountability and oversight. This resulted in a law being passed that includes a new statewide A–F performance accountability system based on student proficiency and growth. It also established charter authorizer accreditation requirements, limiting who can authorize a charter school in Detroit. It put a ban on authorizer-shopping for failing charter schools, and an automatic closure provision that applies only to charters. And a city-level council will assure the production of deep demographic information on the educational needs of Detroit and work with authorizers to better coordinate charter school openings and closings.

The only major provision that lawmakers struck from the legislation was a new Detroit Education Commission that would have had the power to veto the creation of new charter schools in Detroit. Charter supporters were understandably nervous that, in the wrong hands, such a commission could put an end to charter growth in the city, denying opportunities for kids who desperately need them. And because the Commission’s members were to be appointed by Detroit’s mayor, and because the teachers unions have outsize influence in local elections, such an outcome was all too likely. Betsy DeVos, as well as state legislators, saw the threat and opposed the Commission accordingly. That’s no sign of opposition to accountability—it’s the mark of a wise, farsighted political pragmatist that keeps parents and school level educators empowered.

Therefore, if we assume that the policy solutions applied in Detroit and to Michigan charters have any bearing on DeVos’s future plans for the nation, her priorities would comprise support for performance-based accountability, authorizer accountability, automatic-closure for low performing charters, charter autonomy, and data driven coordination of charter openings and closings.

And that’s just in recent years. Over her three decades in education, Betsy DeVos has worked to build bi-partisan support for Michigan’s education policies, including school choice, charters, inter-district public school choice, public online programs, K–3 reading expectations, higher standards, and more.

But even more importantly than all this policy, DeVos has put kids before adults, parents before institutions, and student success before politics. If her experience in Michigan is the measure, I would expect the same from her as Secretary of Education.

Daniel Quisenberry is the president of the Michigan Association of Public School Academies.

If you have any friends concerned with gifted education—or educational excellence in general—you saw them doing cartwheels last week, and for good reason: The final Every Student Succeeds Act accountability regulations were released, and language was added allowing for pro-excellence strategies to be used in states’ K–12 accountability systems (some ideas here and here). This is a huge improvement over No Child Left Behind, which incentivized states to design these systems in ways that gave no credit to schools and educators who moved students into advanced levels of achievement. Providing credit to schools that produce advanced learners has been widely suggested as a way to promote excellence in our schools and society at large, so this was unambiguously great news.

But we also received information last week that should temper the enthusiasm and reinforce the urgency for fostering educational excellence.

The 2015 results from the Trends in Math and Science Study (TIMSS) were released, and as one of the two major international, comparative assessments, the findings are eagerly anticipated every four years. TIMSS always tests grades 4 and 8, and this year they tested high school students in advanced math and science (which they last did in 2008; not every country participates due to conflicts with national college entrance exams). These high-quality assessments are administered under the auspices of the IEA, which is led by a sharp bunch of psychometricians, educators, and policy experts. IEA produces solid data, and my colleagues and I follow their testing programs closely.

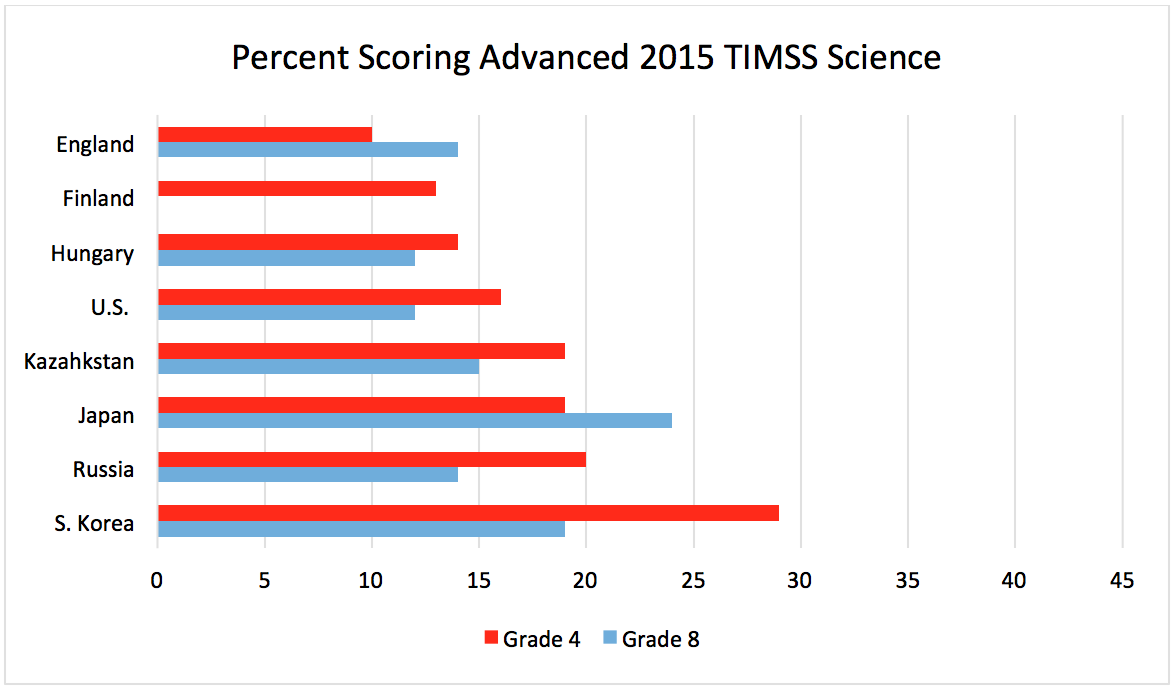

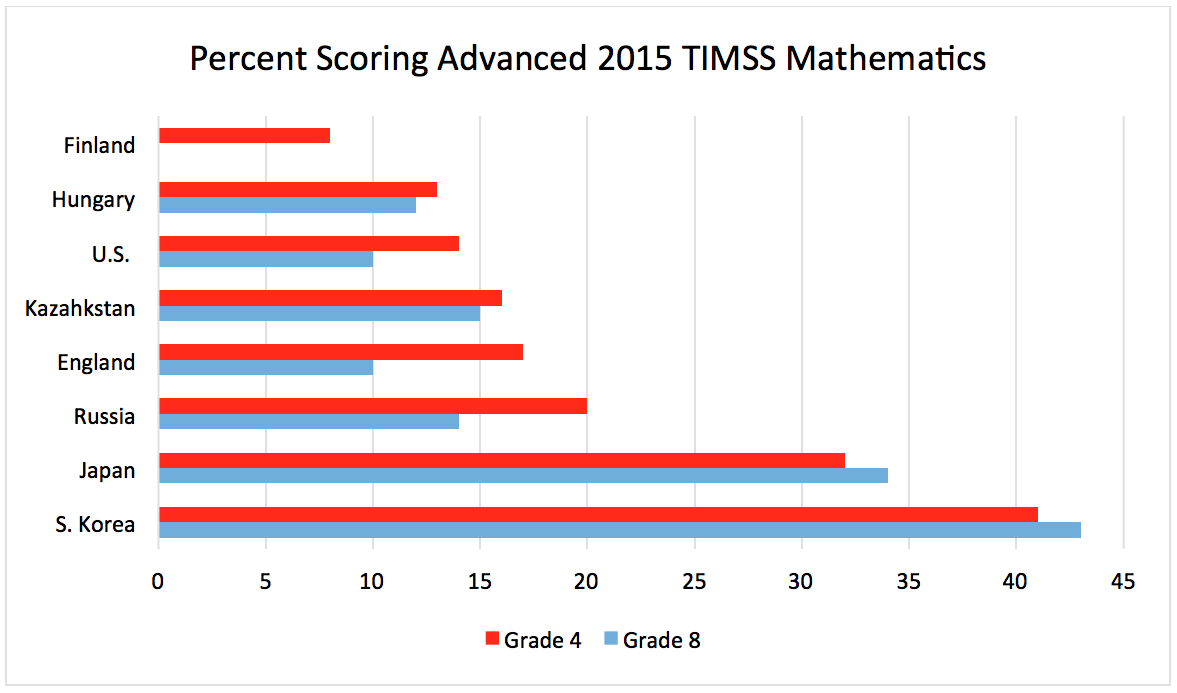

There’s no way to sugarcoat the results: The U.S. produces a much smaller proportion of advanced students than our economic competitors—in some cases far smaller. I include some representative data in the figure below (Finland did not test eighth graders, hence the missing data), and I encourage readers to look through the complete results, which are packed with important and useful information. But it is hard to find positive data about our best-performing students in this data set. (As we edited this post, the 2015 PISA results were released. They provide similar evidence.)

This shouldn’t be the least bit surprising. Despite the condescending assumption among educators and policymakers that our brightest students don’t need much attention—“they’ll do fine on their own”—we have decades of data telling us this is just plain wrong. (See this TIMSS analysis, this NAEP analysis, and this NWEA MAP study, among many, many others.) TIMSS 2015 is only the latest source that makes the case that our general neglect of advanced learning has a price. For example, on the 2015 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), our high-quality national testing program, 7 percent of fourth-grade students, 8 percent of eighth-grade students, and 3 percent of twelfth-grade students performed at the advanced level in mathematics in 2015. As a former science teacher, I found the science data to be even more disturbing: 1 percent advanced in grade 4, 2 percent in grade 8, and 2 percent in grade 12.

When I share these and similar data, critics occasionally argue that the standard for advanced performance on these tests is too high. Ignoring the fact that the standards don’t appear to be too high for students in other countries, the descriptors, sample items, and item maps available for TIMSS and NAEP strike me as evidence that the standards are hardly lofty. Indeed, in looking over these item maps, I was surprised that “advanced” wasn’t more advanced.

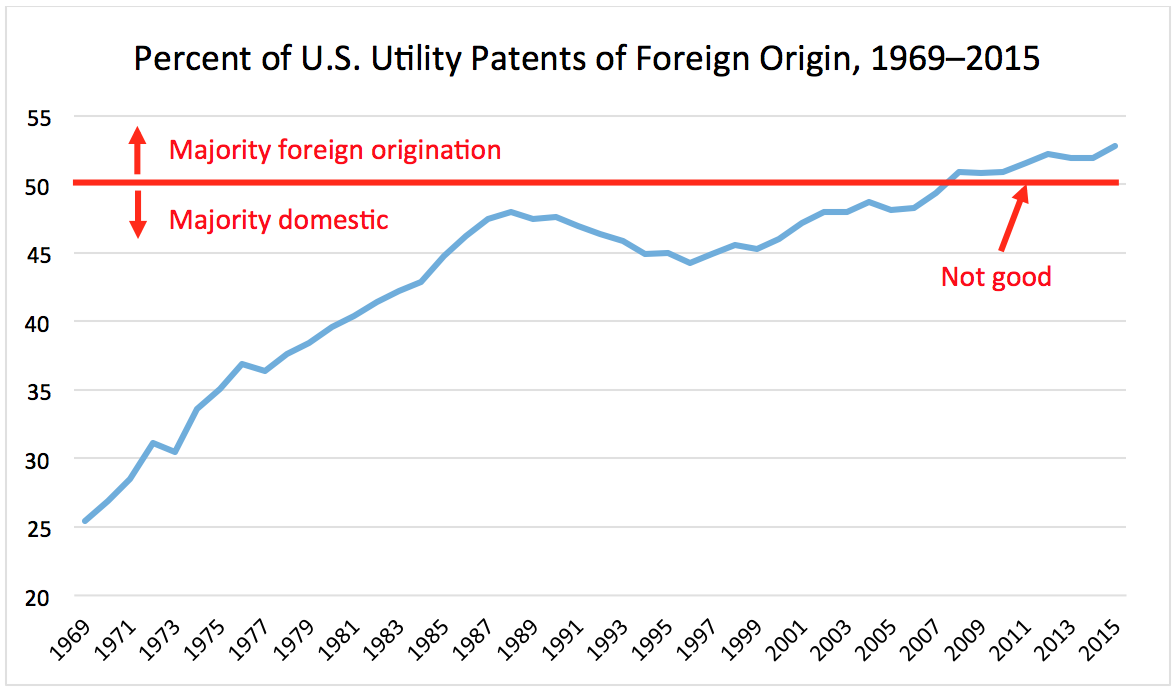

Some have long predicted that turning a blind eye toward advanced learning was going to have serious long-term consequences. I would argue that the evidence of these consequences is all around us, but we haven’t acknowledged it yet. Take, for example, the percent of U.S. patents going to people living outside of the United States:

That’s right, people in the U.S. currently receive less than half the patents issued by our government. That feels like a dangerous trend for a leading indicator of American innovation and economic development. I’m sure people can provide plenty of excuses (or rationalizations) for why this trend isn’t as bad as it looks, but it sure looks pretty bad.

Winston Churchill allegedly said, “Americans can always be counted on to do the right thing…after they have exhausted all other possibilities.” Although this quote is probably apocryphal, a biographer noted that Churchill almost certainly believed this to be true, and we’re proving it true again right now.

We have exhausted all other possibilities. One can even argue that we’ve actively lowered the quality of education for our best students by removing ability grouping, overvaluing “differentiation” as a miracle intervention, and making advanced performance irrelevant to school and district ratings in most state accountability systems. The data make it clear that we are paying the price for this mix of inattention and hostility toward educational excellence. It’s time to “do the right thing,” and a good first step is to ensure that the ESSA flexibility for acknowledging the presence of advanced performance is fully reflected in each and every state’s K–12 accountability system.

Jonathan Plucker is the inaugural Julian C. Stanley Professor of Talent Development at Johns Hopkins University and a member of the National Association for Gifted Children board of directors.

Ever since our president-elect nominated school choice champion Betsy DeVos to be education secretary, there’s been a vigorous debate amongst us education nerds about the proper way to think about school choice. It’s a civil war! Another divide in the reform movement!

Not so fast. Sure, there are disagreements on key policy design issues, but where we differ is dwarfed by our common cause. We don’t have a split as much as a spectrum—a range of views, all of which are worlds away from the position of our opponents in the teachers unions and other parts of the education establishment. (And yes, I say that as someone who has written about our own “schisms.”)

To test the proposition, give the following Buzzfeed-style quiz a try. Check all the boxes that apply to your personal views:

I support a parent’s right to choose the best school for their child, using public funds, as long as that school:

? Is overseen by an elected school board

? Submits to a financial audit on a regular basis

? Follows state class-size mandates

? Adheres to health, safety, and civil rights laws

? Teaches a curriculum aligned to state standards

? Is a brick-and-mortar school (not an online one)

? Doesn’t teach religion

? Is in session at least six hours a day, 180 days a year

? Follows state teacher-pay guidelines

? Participates in annual assessments

? Has at least one librarian, nurse, and counselor

? Does not practice selective admissions

? Demonstrates at least minimal growth in student achievement

? Employs unionized teachers

? Keeps student suspensions to a minimal level

Now give yourself one point for every box you checked.

0–2 points: Congratulations, you are a libertarian! And, in my opinion, naïve about the potential for fraud and abuse in any domain involving taxpayer dollars.

3–5 points: You strongly support parental choice, while understanding that public funding comes with the need for certain safeguards.

6–8 points: You still get to call yourself a reformer but beware of your nanny-state tendencies!

9–15 points: Do you work for the NEA or AFT? You are no friend of parental choice.

***

Personally, I got a “4” on this quiz. The only limitations I’d put on taxpayer-funded parental choice are that eligible schools:

For sure, I disagree with some of my libertarian friends about whether schools that are supported with public funds should have to take state assessments and demonstrate student growth. And I disagree with some of my progressive friends about whether all public schools have to be open to all comers, or be secular. These are important debates.

But these are matters of degree. We all fundamentally agree that parents should get to choose the best school for their children, and we want to keep limits on those choices to a minimum. Our opponents, on the other hand, believe in parental choice in name only.

Something to keep in mind in the days and weeks ahead.

On this week’s podcast, Checker Finn, Robert Pondiscio, and Alyssa Schwenk discuss America’s performance on two recent international assessments, TIMSS and PISA. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines a U.S. Department of Education guide on how to teach writing.

Steve Graham et al., “Teaching Secondary Students to Write Effectively,” The Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education (November 2016).

My respect and appreciation for the Foundation for Excellence in Education is almost boundless, particularly for founder/chairman Jeb Bush and CEO Patricia Levesque. Their “summit” last week in Washington was first rate and their policy advice for state leaders is nearly always sound.

But I (and my Fordham colleagues) must respectfully take issue with several elements of FEE’s “A–F School Accountability Playbook”—advice to states regarding school accountability under the federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA).

There’s much here that we agree with and that states would be well advised to do. Their recommendations for school participation in state testing and for reimagining school report cards are on the mark. So, too, their suggestions for measuring students’ academic growth, gauging the proficiency of ELL students, and using success (not just access or participation) in college-level courses such as AP as the “indicator of school quality or student success” at the high-school level. They’re also right to urge a uniform A-F-style accountability system for all the state’s schools and for singling out the lowest performers in that system for intervention.

All of their ESSA policy recommendations stem from eight principles set forth on the second page of the Playbook. Six of these are absolutely sound; one (see below) is subject to rival interpretations and preferences. But one—number 5 on the FEE list—seems to all of us at Fordham well-intended yet quite wrong. Unfortunately, several of their specific policy suggestions rest upon that erroneous principle.

It says that state policy makers should “Focus attention on the progress of the lowest-performing students in each school.”

Well-intended, to be sure, just as No Child Left Behind was well-intended. Yet it would perpetuate one of the great flaws in—and harms done by—NCLB, namely the absence of incentives or rewards for schools that pay attention to the educational progress of all their pupils.

Of course schools and policymakers should strive in every way to boost the performance of low achievers. But what about high achievers and medium achievers, many of them also poor and wholly dependent on the schools they attend to ensure that they learn as much as they can; to see that they’re challenged every day; and to boost them as far up the ladders of social mobility as the education system is capable of doing?

Plenty of poor and minority kids are medium and high achievers. So are plenty of the children of aggrieved working- and middle-class Americans—people who live in Charles Murray’s “Fishtown” and voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump—who don’t think the country’s major institutions are doing right by them and their families.

They’re just as much the responsibility of schools and state policymakers as the low achievers. It would be a big mistake to worsen their alienation by signaling that the state doesn’t much care how their kids are doing in school or how well their schools are meeting their kids’ needs. And ESSA gives states an overdue opportunity to recalibrate their accountability systems to ensure that this responsibility is taken seriously.

That’s our principled dispute with FEE. And it leads us to demur from several of the Playbook’s specific policy recommendations

First and most important, the recommendation (under “Required Indicator 1: Academic Achievement”) that states focus their principal measure of achievement only on how many students are at/above the “proficiency” bar. This would, once again, perpetuate one of the most damaging features of No Child Left Behind: its disincentive for schools to pay as much attention to kids far below and already above that bar as to those “on the bubble”, i.e. students who are under the bar but close enough to have a reasonable shot at clearing it. In our view, that’s a big mistake. Far better to—as the new federal regs now permit—give schools partial credit for pupil achievement at the “basic” level and extra credit for those reaching the “advanced” level, while of course continuing, as the regs require, to give credit for those attaining proficiency.

Second, while FEE’s suggestion for “Required Indicator 4” is fine at the high-school level, the companion recommendation (apparently aimed at elementary and middle schools)—that states focus only on “growth of the lowest-performing students”—repeats and worsens the problem described in the previous paragraph. Just as FEE (correctly) urges under Required Indicator 2, growth matters for every student and schools should get credit for producing it across the full achievement spectrum, not just at the bottom.

Other issues emerge in the Playbook that we debate within Fordham. FEE’s principle 3, urging states to “Balance measures of student performance and progress,” is open to multiple interpretations. By “balance,” do they mean give equal weight to progress and to performance within a school? Some of us at Fordham think that a fifty-fifty distribution is spot on. Others believe that growth should count much more heavily.

We’re also keenly aware of both the pros and cons of giving schools a single summative grade, as FEE favors (and as Florida and several other states do). Most of us would prefer a school report card that, like a child’s report card, contains several grades. Sure, they can be totaled and averaged into a GPA by anyone who wants to—but most of us think the state will better inform parents, educators, and taxpayers if it gives—for example—separate grades to a school for achievement and for growth, for graduation and student success, for ELL students and perhaps gifted students, and so on. Averages will inevitably be calculated; we’re just not sure that’s the best use of a report card from the state itself.

That said, we still revere FEE and agree with it on just about everything else!

A new report from the Center for Reinventing Public Education investigates state-initiated turnarounds, which are intended to improve student achievement in the lowest-performing schools or districts. Such interventions can be difficult to implement successfully and even more difficult to sustain after the initial goals have been achieved. To that end, the report examines ways states can ensure their turnaround strategies are effective and long-lasting.

In the introduction, author Ashley Jochim discusses how the Every Student Succeed Act puts the “responsibility for improving student outcomes” back in the hands of the states and enables them “to craft their own ‘evidence-based’ turnarounds.” However, she asserts that the evidence for such evidence-based turnarounds is sorely lacking. So to inform states about various strategies and the conditions needed for them to succeed, the report examines eleven different initiatives in eight states and how they affect student outcomes.

Jochim reviewed state policies, analyzed studies about the effectiveness of turnaround initiatives, and interviewed stakeholders, such as state chiefs, district staff, educators, and community groups.

In this sample, she identified five distinct types of state-initiated turnarounds: state-supported local turnaround, state-authorized turnaround zones, mayoral control, state-led school takeover, and state-led district takeover. (Studies on mayoral control did not meet the criteria to be included in the analysis, so the report only examines the other four.) For each, Jochim identifies whether it focuses on a school or a district, distinguishes who leads the turnaround effort, discusses the level of authority the state has in each type of approach, and gives examples of each strategy being utilized and the results.

Ultimately, the report identifies four key ingredients that are necessary for any of the five types of turnaround strategies to have a chance of success—will, authority, capacity, and political support. It finds all of the turnaround methods analyzed to be viable options, but emphasizes that each has its own strengths and weaknesses, which may lead to success in some locales but failure in others. States should therefore consider specific circumstances to find the best fit—factors such as local leadership, available resources and talent, and the extent or reach of the turnaround. No matter the path leaders choose, however, Jochim recommends it be based in evidence, aided by both local and outside stakeholders, and comprise multiple strategies. Massachusetts, for example, was the only state to use a combination of approaches, and it saw statistically significant math and reading gains in its Springfield Empowerment Zone Partnership.

The report provides valuable information for states looking to address the issues in low-performing schools and districts. Using multiples strategies and understanding the limitations and advantages of local factors can increase the likelihood of turnaround success and ultimately help children in low-performing schools get the quality education they deserve. Any state looking to undertake such a task should certainly use this report to become knowledgeable about the options out there.

SOURCE: Ashley Jochim, "Measures of Last Resort: Assessing Strategies for State-Initiated Turnarounds," Center for Reinventing Public Education (November 2016).

A new National Council on Teacher Quality report argues that higher admission standards in teacher preparation programs attract higher-quality teaching candidates and produce more effective educators.

From 2011 to 2015, several states and the Council for the Accreditation of Educator Preparation (CAEP) raised admission requirements for teacher preparation programs. Yet this change was short-lived. By 2016 CAEP backed away from their more rigorous requirements in response to criticism that the higher standards resulted in a less diverse teaching force and exacerbated teacher shortages. While enrollment in teacher preparation programs did drop from 2009 to 2014, NCTQ contends that this was a result of the difficult economic times and not caused by CAEP’s higher application standards—which NCTQ argues are still necessary if teacher preparation programs are to recruit high-quality applicants.

The study backs up these claims by pulling together data from various sources. It looks at the admission requirements of 221 elementary teacher education programs from twenty-five states, as well as data from a forthcoming NCTQ report, and a survey of college students conducted by the organization Third Way. From these, NCTQ shows that many states are already able to meet stricter requirements and argues that maintaining higher standards will likely attract better quality applicants, while having little to no effect on their number or their racial diversity.

Using results from the National Online Survey of College Students administered by Third Way, NCTQ found that, in a sample of 400 non-education major students, over 50 percent of students with a high GPA (3.3 or higher) see education as an “easy” major, and as a result, are discouraged from pursuing a career in education. The survey also found that 58 percent of students reported that they would show more interest in teacher preparation majors if application standards were more rigorous. This suggests that higher standards will not only result in more candidates, but also better qualified candidates.

Moreover, NCTQ found that, of the 221 teacher preparation programs it studied, the majority were on track to meet higher minimum average GPA or test score requirements while still accepting an adequate number of applicants. This was true of 72 percent of teacher preparation programs in states that require a program’s incoming class to have an average GPA of 3.0. Similarly, of the states that adhere to CAEP standards, 53 percent are currently likely still able to meet the more rigorous standards CAEP implemented (but later reversed) in 2011.

NCTQ’s also makes the case that higher standards won’t significantly reduce program diversity. This factor is important, especially given studies that have found improved student outcomes in classrooms in which teachers and students are the same race. Thankfully, selective teacher prep programs don’t necessarily result in less diversity. Thirteen percent of undergraduate elementary education programs are able to have high admission standards while maintaining a diverse student body. Although the percentage is low, it still attests that diversity and quality can effectively coexist.

Excellent teachers are absolutely necessary if we are to continue improving student outcomes—so states ought to heed NCTQ’s guidance that higher admission standards to teacher preparation programs must be maintained to attract higher-quality applicants. There are many areas for improvement within teacher preparation programs, but being more selective with whom they admit is a quick first step in ensuring that more high-quality teachers end up in our schools.

SOURCE: Kate Walsh, Nithya Joseph, and Autumn Lewis, “Within Our Grasp: Achieving Higher Admissions Standards in Teacher Prep,” National Council for Teacher Quality (November 2016).