A better way to measure student absenteeism

For many parents and teachers, the Covid experience has confirmed at least two pieces of common sense: It’s hard for kids to learn if they’re not in school, and those who are in school tend to learn more.

For many parents and teachers, the Covid experience has confirmed at least two pieces of common sense: It’s hard for kids to learn if they’re not in school, and those who are in school tend to learn more.

For many parents and teachers, the Covid experience has confirmed at least two pieces of common sense: It’s hard for kids to learn if they’re not in school, and those who are in school tend to learn more. Yet in some communities, the crisis persists, thanks to one of the pandemic’s most pernicious effects: the surge and apparent normalization of student absenteeism, especially in the many low-income communities that have been slammed by the virus.

Nationally, one in four students was chronically absent in 2020, and it’s not over: 59 percent of Detroit students and nearly half of Los Angeles Unified students are on pace to fit that category in 2021–22. In many parts of America, enrollment data show tens of thousands of students to be simply missing, even after accounting for increases in charter, private, and homeschool enrollment.

A focus during the post-Covid education recovery phase, then, should be making sure that students return to school on a regular basis. Yet our systems for measuring their attendance—and holding schools accountable for getting kids back into classrooms—are woefully inadequate and antiquated.

Most jurisdictions rely exclusively on raw attendance rates and/or chronic-absenteeism rates, both of which are highly correlated with student demographics and other factors that schools generally cannot control. Yet such metrics are ubiquitous in state accountability systems, with at least thirty states and the District of Columbia having adopted student absenteeism, chronic absenteeism, or variants thereof as a “measure of school quality” under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Moreover, many states and districts do a poor job of measuring attendance because they can’t (or choose not to) differentiate between full-day absences and partial-day ones (as in, when students show up for some classes but not for others). Prior research shows that partial-day absenteeism is rampant in secondary schools, mostly unexcused, and explains more missed classes than full-day absenteeism. Partial-day absences increase with each middle school grade and then rise dramatically in high school.

In short, the most widely adopted “fifth indicator” under ESSA has been framed in ways that are hopelessly broad and unfair. But why? After all, collecting detailed attendance data ought to be straightforward in the era of smart phones and Snapchats. And nothing prevents states from designing more sophisticated attendance and absenteeism gauges, as they already do when it comes to test scores. Just as “value-added” calculations derived from those scores help parents and policymakers understand schools’ impact on students’ achievement, so too might a measure of schools’ “attendance value-added” complement raw attendance or chronic-absenteeism rates by highlighting schools’ actual impact on attendance—after taking into account students’ preexisting characteristics and behavior. Such an approach is also fairer, as it doesn’t reward or penalize schools based on the particular students they serve. But what’s more important, in our view, is that if “attendance value-added” were baked into accountability systems, it might encourage more schools and districts to embrace changes that actually boost attendance—which, of course, is the whole point!

For instance, some schools form task forces to closely monitor attendance so as to catch problems early, such that three absences might raise a warning flag that triggers a parent phone call. They make home visits if parents can’t be reached by email or phone. They refer students with frequent absences to the school counselor or social worker for case management and counseling. They establish homeroom periods in high school, where students remain with the same teacher all four years so that they form relationships, making it easier for the educator to monitor and discuss attendance with pupil and family.

We wanted to know whether these types of efforts might be isolated and reliably measured such that schools get credit (or don’t) for making them. Thus Fordham’s new study, Imperfect Attendance: Toward a fairer measure of student absenteeism, by Jing Liu, assistant professor of education at the University of Maryland and the author of numerous studies on the causes and effects of student absenteeism. Liu leveraged sixteen years of administrative data (2002–03 to 2017–18) from a large and demographically diverse district in California where the attendance information included data on partial-day absences. It’s worth your time to read the (fairly short) study and Jing’s policy implications, but for those in a rush, here are four key findings:

There’s much to unpack here, but to us, four takeaways merit attention.

First, better attendance measures could help students and families make better decisions.

On average, attending a high school with high attendance value-added increases a student’s attendance by twenty-eight class periods (or roughly four school days) per year. And there is suggestive evidence that high schools that do an above-average job of boosting attendance also boost postsecondary enrollment—even if the school’s test-based value-added is middling.

That is to say, just as there are high-test-value-added but low-achievement schools that help students succeed, there are high-attendance-value-added but low-raw-attendance schools that also do this.

Many low-income parents face a choice between two schools with similar achievement and attendance patterns but with value-added scores that vary widely. Helping them to understand and act upon those distinctions is essential. We want parents to choose schools that are “beating the odds,” and value-added measures are one good way to identify these schools.

Second, better attendance measures have real-world implications for educators.

One of the reasons for measuring a school’s impact on attendance is to be able to hold school staff accountable for what’s under their control. Plus, we want to encourage behavior that will make it likelier that students will come to school so they can learn more. Value-added measures are the best way to do that. Simply put, attendance value-added differentiates between high-poverty schools that deserve to be lauded and those that demand intervention.

Likewise, we need to worry about discouraging teachers and principals who choose to work in high-poverty schools and who may be getting unfairly penalized when, in reality, they are making progress in improving student attendance, even if the “status” measures remain unsatisfactory.

All that said, this study is the first to explore the feasibility of attendance value-added, and we need other researchers to test the measure empirically—with larger samples and in other locales—before it’s ready for prime time. What’s more, though the study undoubtedly demonstrates the promise of attendance value-added, it also underscores the strength and utility of test-based value-added measures—and why we’d be foolish to move away from them.

Third, more information is better.

The message from this study isn’t that schools should stop reporting raw attendance rates and chronic absenteeism. Instead, a both/and rather than either/or approach is the right choice. In fact, we’d go so far as to suggest that, just as some states have two grades for schools based on test scores (one for achievement and one for growth), we should consider having two measures of attendance (chronic absenteeism and “value-added” measures, once they’re vetted).

In general, status measures and growth measures are apples and oranges, so it doesn’t make sense to average or aggregate them. The simplicity and usefulness of a single, summative grade is lost if it doesn’t serve any one purpose well.

For instance, if the purpose is to decide whether to renew a school’s charter for the next five years, that decision should rest on growth-based test-score measures. But if the purpose is to understand whether students are ready for college and career, status-based measures are best. Each tells us something different. So it is with chronic-absenteeism rates and attendance value-added.

Finally, school safety matters when it comes to student attendance.

With wonky empirical studies such as this one, practitioners understandably ask, “What do these study findings imply for my work in real schools and classrooms?”

Although we hesitate to rely too heavily on correlational evidence, student-survey data consistently show that the strongest links to attendance value-added have to do with students’ sense of safety at school and their perception that the rules and behavioral expectations are clear.

In other words, staff who earnestly want to improve attendance rates should be mindful that safe schools and coming to school go hand in hand.

—

Cultivating a positive school culture—one that prioritizes student engagement, safety, and high expectations—is a key piece of the attendance puzzle. But so is developing a novel way to isolate and measure a school’s impact on attendance so that the efforts (or lack thereof) of those who work there can be made visible.

To repeat, one in four American students was chronically absent in 2020, up from one out of six in 2017–18. Thankfully, buildings have now reopened, but it’s past time to get all our kids back in school.

NOTE: This editorial is adapted from Michael J. Petrilli's public comment on the U.S. Department of Education's proposed Charter Schools Program regulations, available here.

Thirty years ago, when the charter school movement was just getting off the ground, devotees of big-city school systems worried that these new options would drain critical funding, hurt the kids left behind, and worsen an unequal and unjust system. It wasn’t a crazy concern, given what had happened over the previous thirty years—from the 1960s through the 1980s—when White flight (and middle-class Black flight) from the cities to the suburbs very much hurt urban schools, leaving them with less money and a significantly less-advantaged pupil population.

In recent years, however, it has become ever clearer that this concern about charter-inflicted damage was misplaced. Indeed, one of the most consistent findings of modern social science is that the expansion of charter schools has helped, not hurt, students who remain in district-operated public schools. And in at least a handful of big cities, including Washington, Miami, and Indianapolis, the growth of charters has sparked vigorous reforms to school systems that are paying off in terms of stronger student outcomes. Charter expansion turns out to be a rising tide that lifts all boats, not a life raft that leaves some children behind.

Yet this positive news seems not to have reached officials at 400 Maryland Avenue, Southwest, headquarters for the U.S. Department of Education. Its draft regulations for charter school start-up and replication grants, published last month, rest on the faulty, outdated notion that charter school expansion has a negative impact on traditional public schools. If these regulations go into effect, they could grind the charter movement to a halt. That would be bad for all students—those enrolled in public charter schools, for sure, but also those attending traditional public schools.

In its draft regulations, the Department proposes that all applicants for charter start-up or replication grants submit “a community impact analysis that demonstrates that there is sufficient demand for the proposed project and that the proposed project would serve the interests and meet the needs of students and families in the community or communities from which students are, or will be, drawn to attend the charter school.” The analysis must include, among many other provisions, “Evidence that demonstrates that the number of charter schools proposed to be opened, replicated, or expanded under the grant does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community, including projected enrollment for the charter schools based on analysis of community needs and unmet demand and any supporting documents for the methodology and calculations used to determine the number of schools proposed to be opened, replicated, or expanded.”

This language indicates that Department officials believe that new charter schools should only be launched in communities with rising student enrollment or some shortage of school capacity. Yet, as folks surely know, almost every school district in the country, and especially large urban districts, are facing flat or declining enrollment currently because of the post–Great Recession “baby bust,” the pandemic-era slowdown in immigration, and the exodus of students to nondistrict options in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. Thus, few applicants will be able to provide evidence that “the number of charter schools proposed to be opened, replicated, or expanded under the grant does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community.”

Furthermore, this language is at odds with the statute itself. The Every Student Succeeds Act states that one purpose of the Charter Schools Program (CSP) is to “increase the number of high-quality charter schools available to students across the United States.” Requiring evidence that “the number of charter schools proposed to be opened, replicated, or expanded under the grant does not exceed the number of public schools needed to accommodate the demand in the community” clearly contradicts the statutory purpose of the CSP.

Rather than ask whether there are enough seats in public schools writ large, the Department might wonder whether there are enough seats in high-quality public schools—in either the district or charter sector. That question would result in a very different answer in terms of community demand.

Moreover, slowing or stopping the growth of public charter schools in communities with flat or declining enrollment is bad for racial equity. That is the clear takeaway of two recent studies finding that the growth of charter schools boosts achievement overall for students in a given community, including students in traditional public schools, while it also closes racial achievement gaps.

The first, a 2019 Fordham Institute report titled Rising Tide: Charter School Market Share and Student Achievement, found a positive relationship between the percentage of Black and Hispanic students who enrolled in a charter school at the district level and the average achievement of students in these groups—at least, in the largest urban districts. The second, by Tulane University’s Feng Chen and Douglas N. Harris, found a positive relationship between the percentage of all students who enrolled in charter schools and the average achievement of all publicly enrolled students, especially in math.

Now, both of those studies—which include more than nine out of ten American school districts and nearly twenty years of data on charter school enrollment—have been updated in 2022 with additional years of data and estimates, and their findings continue to converge.

Both studies find that charter schools’ overall effects are overwhelmingly positive. For example, according to the Tulane study, moving from 0 to greater than 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts the average school district’s graduation rate by at least three percentage points. Meanwhile, the Fordham study suggests that a move from 0 to 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts math achievement for all publicly enrolled students by at least one-tenth of a grade level.

Both studies also find that achievement gains are concentrated in major urban areas, consistent with much prior research on charter school performance. For example, according to the Tulane study, moving from 0 to greater than 10 percent charter enrollment share in the average school district is associated with a 0.13 standard-deviation increase in math achievement. But in metropolitan areas, this change is associated with a 0.21 standard-deviation increase in math scores.

Finally, both studies find that poor, Black, and Hispanic students see big gains. For example, according to the Fordham study, a move from 0 to 10 percent charter school enrollment share boosts math achievement for these children by about 0.25 grade levels. Poor students also see a 0.15 grade-level increase in reading achievement.

These findings are incredibly important, given longstanding concerns that the growth of charter schools would hurt students in traditional public schools. That appears to be the motivation behind the Department’s proposed Community Impact Analysis. Yet that’s simply not true.

As charter schools grow and replicate, parents gain access to high-quality schools that better meet their children’s needs, students who remain in traditional public schools see better outcomes, and racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps that have resisted many other well-intentioned reforms begin to close. It’s likely that this is happening because the expansion of high-quality charter schools encourages districts to improve in order to retain families and because better charter schools squeeze bad charter schools out of the local market.

Furthermore, another recent Fordham Institute study, this one by self-professed charter skeptic Mark Weber, found that the fiscal impact of charter school growth on traditional public schools is not negative, as charter opponents claim. In most states, an increase in the percentage of students attending independent charter schools was associated with a significant increase in their host districts’ total revenue per pupil, total spending per pupil, local revenue per pupil, and per-pupil spending on support services. Notably, host districts’ instructional spending per pupil also remained neutral to positive in all twenty-one states.

At the very least, the federal Education Department should revise its required community impact analysis to look at capacity in high-quality schools, rather than total capacity in schools writ large. It could also ask applicants to provide data on other indicators of demand, such as charter school waiting lists.

Even better would be to rethink these proposed regulations altogether, given that they fail to “follow the science.” That’s no cardinal sin; as my coeditors and I write in our recent book Follow the Science to School, “the science” is always changing. That’s why we must follow it. Concerns about the “community impact” of charter schools weren’t unreasonable thirty years ago, but now we can put them to rest—which is what the Biden Administration should do with these proposed rules.

A 2018 Pew Research Center study demonstrated the perhaps surprising fact that the United States remains a robustly religious country, indeed the most devout of all the wealthy Western democracies. Ours was the only country out of 102 examined that had higher-than-average levels of both prayer and wealth. And while average rates of religiosity are declining and people are increasingly identifying as religiously unaffiliated, the percentage of Americans who are deeply religious has remained steady. Also perhaps surprising: This includes something like one quarter of all teenagers. In her new book, God, Grades, and Graduation, sociologist Ilana M. Horwitz delves deeply into teens’ lives in search of potential connections between religiosity and educational outcomes.

Primary data come from the National Study of Youth and Religion (NSYR). Beginning in 2002–03, NSYR surveyed 3,290 kids between thirteen and seventeen, as well as one of their parents. Analysts collected four waves of data, completing the study in 2012–13. Horwitz connects NSYR respondents with data in the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC) to track college attendance and outcomes. She also included data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health). Add Health, based at the University of North Carolina, surveyed approximately 20,000 students in grades 7–12 and one of their parents starting in 1994–95 and has continued to follow them over the past twenty-five years.

Horwitz focused her analysis on Christianity, as it is the most common religious affiliation reported in the U.S and encompasses a huge number of denominations and subgroupings. She is most interested in religious intensity, breaking out her subjects into three groups: atheists, non-religious theists, and the group she calls “abiders”—those who expressed the deepest, most life-encompassing faith. The bulk of the book looks at abiders—including numerous case studies of individuals across the socioeconomic, social class, and geographic spectra—and how their faith has intersected with their education trajectories. In a nutshell, strong religious faith appears to boost students’ educational attainment in high school—both GPA and graduation—while constraining their postsecondary outcomes.

Horwitz makes the case that the main purpose of secondary school is not gaining knowledge or critical thinking skills but learning how to behave and perform in a rules- and standards-driven environment. Specifically, schools tend to reward students for their ability to demonstrate certain “values, dispositions, and tastes that characterize the middle and professional class.” She goes so far as to suggest that these are the hallmarks of the “White Protestant status culture” upon which the public common school was founded. Who better to flourish in such an environment than those for whom the same ideals—cooperation, conscientiousness, good behavior, self-discipline, and high motivation—are practiced deeply at home and at church? Evidence suggests that these traits, when internalized and fully embraced, act as “guardrails” against negative behaviors and replicate aspects of the “social capital” enjoyed by higher income youth among those who may lack resources and supports and thus may typically be at risk of falling through the cracks.

Merit-based achievement in school is typically found in greatest supply among those already at the top in terms of family advantage. But evidence abounds in NSYR that those who follow the rules laid down by God, parents, and adult authorities gain an academic advantage—an approximately 10 percentage point bump over non-abiders—in course grades and GPA. This bump exists for both genders, all races, and for students from all socioeconomic strata. The same bump cannot be found in test scores—God won’t give out answers to the algebra final no matter how zealously one prays—but all the subjective measures that go into teachers’ final grades seem to be positively impacted.

However, the abider advantage takes an interesting turn after students step off the high school graduation stage. While thirty-two of every one hundred non-abiders in NSYR earned a bachelor’s degree, forty-five of every one hundred abiders did the same. So far so good. But abiders significantly “undermatch” in terms of college matriculation. Those who took home As and Bs in high school earn degrees from colleges with entering students’ average SAT scores 22 points lower than the average at colleges attended by comparable non-abiders who also got As and Bs in high school. Despite the high school advantage they experienced, abiders are going to (and graduating from) less-selective colleges. This is especially true of high-income abiders, whose double advantage is largely set aside and whose undermatch was largest of all.

Part of it, Horwitz argues, is that college is less about following the rules and more about doing the academic work. Test scores still matter for upper echelon institutions, devaluing the observed abider advantage. But abiders also reported being less interested in being accepted at more selective colleges—even those with the requisite SAT scores. A lack of interest on the part of many abiders in leaving home to attend a college that’s far away from family, church, and community—especially a college that’s perceived to be rife with distraction or temptation—drives this mindset. Living at home and commuting to Hometown U fills the bill just fine. Anecdotes from numerous abiders in NSYR show them ceding agency in their future to God. The goals that their faith has led them to adopt don’t call for rigorous postsecondary education, and even those with degrees were often in low-wage jobs in their mid-twenties as they awaited the call for whatever came next. Income levels for abiders in the workforce were markedly lower than their non-abider peers with similar educational attainment—the largest gaps once again concentrated among students from higher-income families. This likely comes from both the caliber of institutions from which they graduated as well as their post-graduation job choices.

Expression of religious faith takes many forms in America today. Horwitz’s deep dive into the lives of devoutly religious Christian young people clearly shows how faith interacts with important aspects of their lives, including education. The book covers a lot of ground and is a recommended read for any who have an interest in the topic and want to understand the academic journeys of students today.

SOURCE: Ilana M. Horwitz, God, Grades, and Graduation, Oxford University Press (2022).

As beloved TV personality Fred Rogers once quipped, “Play gives children a chance to practice what they are learning. . . . It’s the things we play with and the people who help us play that make a great difference in our lives.”

But when it comes to best supporting children’s learning and development, is play as good as adult-led, direct instruction? A new meta-analysis by researchers at the University of Cambridge examines this important question, specifically focusing on the effectiveness of guided play. The study is the first to synthesize the evidence on the effectiveness of guided-play interventions on children’s learning and summarizes how guided play is conceptualized and operationalized across multiple studies.

As the authors define it, “guided play” is a midpoint between free play and direct instruction. It occurs when an adult has a clear learning goal in mind when initiating an activity or play but still allows children freedom and choice over their actions.

Researchers reviewed thirty-nine studies on guided play and included seventeen in the meta-analysis. The children in these studies ranged from one to eight years of age, and the analyses assessed the impact of guided play versus free play and direct instruction on a variety of outcome measures, including cognitive and academic learning (specifically, literacy and math skills), social and emotional development, and physical development (such as gross motor skills).

The meta-analysis found that “guided play, relative to direct instruction, had a small to medium positive effect” on two numeracy outcomes: early math skills and shape knowledge. It had a medium effect on “task switching”—i.e., shifting attention between one task and another when directed. However, the researchers found weak or no evidence that guided play benefits other key math outcomes, such as spatial skills and math vocabulary, and also doesn’t improve children’s literacy skills, behavioral regulation, inhibitory control, or socioemotional development more than direct instruction.

While the results of this analysis provide some evidence that guided play may be useful in helping young children master some early mathematical concepts and skills, it’s important to take several major limitations into account when drawing conclusions about how best to support our youngest learners.

First, there is a very high level of heterogeneity across the studies. Participant numbers varied widely; only five of the studies analyzed included a sample size of over 200 children. Importantly, the guided play studied was also not limited to learning in early-childhood classrooms; “studies were also included if they were carried out in laboratory-based, museum, or home environments,” and thus, the type of adult leading the play ranged from parent to teachers, researchers, therapists, and more. Curiously, studies in which researchers directed the guided play found more evidence that it positively impacted children’s learning outcomes than those directed by other adults, including teachers.

The studies also varied in design and were conducted over several decades in different countries with varying levels of income inequality. The amount of exposure to guided play also varied significantly between studies, as did the size of the classroom or group of students assessed and how “guided play” was conceptualized (likely resulting in varying levels of adult guidance and child choice across studies).

Another major consideration is that the children’s ages varied widely. While most studies reported on children between three and six years old, the population studied in others ranged from one to eight years old. Surely, the time devoted to “guided play” should vary significantly depending on whether a child is learning how to take his or her first steps or is sitting in a second- or third-grade classroom, working to master reading comprehension and beginning to tackle multiplication and division.

And finally, as the study authors themselves note, “many of the included studies were assessed as having a high risk of bias due to lack of blinding, lack of using random sequence generation, and/or failure to report sufficient information on allocation concealment and selective reporting.”

In short, although this study sheds some light on the benefits of play-driven learning, given the limitations noted above, any interpretations of the results should be made cautiously. Particularly at a time when more and more children are falling behind academically and socially due to the ongoing pandemic, much more research is needed to better understand how guided play affects various student outcomes and how these may vary based on learning environment, delivery, and student demographics.

As the mother of two energetic preschoolers, I also urge parents, educators, and caregivers of preschoolers to be mindful of the huge benefits of nonguided, free play, both in and outside of the classroom. Particularly in the toddler years, it’s important that toddlers play supervised but independently and not interrupted by a parent or caregiver. Unlike guided play, this type of play is child driven, independent from adults, and valuable for young kids. While I have certainly been guilty of interrupting my kids when they’re playing and don’t truly need me, adults should notice when toddlers are engaged and give them space until their attention wanes. Quality play also doesn’t require expensive, fancy, app-based, or numerous toys (in fact, young children tend to get overwhelmed and have a hard time figuring out what to do when given too many choices, which will make sense if, like me, you’ve ever spiraled into indecision when faced with the million choices on a Cheesecake Factory menu). So if you want to foster independence, creativity, and a love of learning through play in your preschooler, pare it down and rotate in and out simple, child-led toys, like the ones you grew up playing with—and make sure they are accessible and convenient. And most importantly, avoid the temptation to interrupt your child if he or she is engaged in a toy or book.

The reviewer's son hard at play. Image courtesy of Victoria McDougald.

It’s also important to let kids play with what they like. Since he was an infant, my son has loved playing with small toy cars and trucks. Now four, he will play independently for long periods of time with his Hot Wheels, inventing racing tournaments, designing and drawing racetracks, coming up with creative names for all of his cars and drivers, and sometimes just driving his vehicles in the dirt. He also loves all things STEM related, so I recently took him to a free STEM story and playtime at our local library. After two full hours of watching him independently construct plastic cars, robots, and “create-a-chain” reaction ramps, happy as a pig in mud, I finally had to drag him away for quiet time and some lunch. Similarly, while my two-year-old daughter has little interest in playing with my vintage dolls and Barbies (sob), I’ve tried to embrace her love of Peppa Pig and serving us endless plates of food from her wooden play kitchen. If you tailor toys to the interests of each child, it drives more play.

And as Susie Allison (aka Busy Toddler) recently stressed, “If you’re seeing your child play, you’re seeing the foundation built.” Doing so will likely help them become better learners, more autonomous, and happier students later in life.

So play on, but don’t write off the value of traditional instruction yet!

SOURCE: Kayleigh Skene, et. al, “Can guidance during play enhance children’s learning and development in educational contexts? A systematic review and meta-analysis,” Child Development (March 2022).

This whopping new report from a special committee of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) is a whopping disappointment.

Though the fifteen committee members are mostly quite accomplished in their fields, beginning with the able Adam Gamoran, president of the W.T. Grant Foundation, who chaired the group, it’s important to note that thirteen of them—all but Gamoran and Norma Ming, research supervisor for the San Francisco school system—work at major research universities. For all the heavy emphasis on “equity” in their report, not a single panelist came from an HBCU, a community college, a regional university, a religious institution, or the worlds of education policy and practice. Needless to say, none was chosen to represent parents, teachers, students—or even taxpayers. These are academic researchers, many with IES grants of their own, opining on the future of education research.

Yes, they proffer some worthy ideas for IES’s two research centers, such as supporting studies that make imaginative use of artificial intelligence and “big data.” But a slew of their recommendations are misguided and, if followed, would do more harm than good.

Particularly egregious examples include the following:

And then there are the blind spots and omissions. Nowhere in this fat volume does the panel suggest that IES do anything in such key realms as early-childhood education, private schools, homeschooling, civics education, community colleges, regional public universities, or adult education. Nor—despite their push for more different kinds of “outcomes”—do they ever mention such crucial postschool outcomes as employment, earnings, and citizenship.

As I understand it, what the twenty-year-old IES was seeking from NASEM in this review (as in two others, one focused on NAEP and the other on NCES), was constructive suggestions toward a blueprint or agenda for the next five years of federally supported education research—what topic areas should be added, which ones needed refreshing, perhaps which could be retired, plus advice regarding institutional accountability and transparency and so forth. Yet that’s mostly not what was delivered. Sorry, National Academies, but what we’re seeing in this tedious document looks more like an overweight specimen of veteran high-status education researchers washing each other’s hands while singing about equity.

SOURCE: Adam Gamoran and Kenne Dibner, eds., “The Future of Education Research at IES: Advancing an Equity-Oriented Science,” The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (March 2022).

By Amber M. Northern and Michael J. Petrilli

For many parents and teachers, the Covid experience has confirmed at least two pieces of common sense: It’s hard for kids to learn if they’re not in school, and those who are in school tend to learn more.[1] Yet in some communities, the crisis persists, thanks to one of the pandemic’s most pernicious effects: the surge and apparent normalization of student absenteeism, especially in the many low-income communities that have been slammed by the virus.

Nationally, one in four students was chronically absent in 2020,[2] and it’s not over: 59 percent of Detroit students are on pace to fit that category in 2021–22.[3] In many parts of America, enrollment data show tens of thousands of students to be simply missing, even after accounting for increases in charter, private, and home school enrollment.[4]

A focus during the post-Covid education recovery phase, then, should be making sure students return to school. Yet our systems for measuring their attendance—and holding schools accountable for getting kids back into classrooms—are woefully inadequate.

First, most jurisdictions rely exclusively on raw attendance rates and/or chronic-absenteeism rates, both of which are highly correlated with student demographics and other factors that schools generally cannot control.[5] Nevertheless, such metrics are ubiquitous in state accountability systems, with at least thirty states and the District of Columbia having adopted student absenteeism, chronic absenteeism, or variants thereof as a “measure of school quality” under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Second, many states and districts do a poor job of measuring attendance because they can’t (or choose not to) differentiate between full-day absences and partial-day ones (as in, when students show up for some classes but not for others). Prior research shows that partial-day absenteeism in secondary school is rampant, mostly unexcused, and explains more missed classes than full-day absenteeism.[6] Part-day absences increase with each middle school grade and then rise dramatically at the transition to high school.

In short, the most widely adopted “fifth indicator” under ESSA has been framed in ways that are hopelessly broad and unfair. But why? After all, collecting detailed attendance data ought to be straightforward in the era of smart phones and live tweets. And nothing prevents states from designing more sophisticated attendance and absenteeism gauges, as they already do when it comes to test scores. Just as “value-added” calculations derived from test scores help parents and policymakers understand schools’ impact on students’ achievement, so too might a measure of schools’ “attendance value-added” complement raw attendance or chronic-absenteeism rates by highlighting schools’ actual impact on attendance—after taking students’ preexisting characteristics into account. Such an approach is also fairer, as it doesn’t reward or penalize schools based on the particular students they serve. But what’s more important, in our view, is that if “attendance value-added” were baked into accountability systems, it might encourage more schools to embrace changes that actually boost attendance.

For instance, some schools form task forces to closely monitor attendance to catch problems early, such that three absences might raise a warning flag that triggers a parent phone call. They make home visits if parents can’t be reached by email or phone. They refer students with frequent absences to the school counselor or social worker for case management and counseling, as needed. They establish homeroom periods in high school, where students remain with the same teacher all four years so that they form relationships, making it easier for the educator to monitor and discuss attendance with the child and family.

We wanted to know whether these types of efforts might be isolated and reliably measured such that schools get credit (or don’t) for making them. To that end, this study examines the following:

1. Whether conventional measures of student absenteeism reflect high school students’ individual characteristics rather than high schools’ effects on attendance.

2. Whether high schools vary in their “attendance value-added.”

3. Whether test-based value-added and attendance value-added are correlated and how well each predicts long-run outcomes, such as postsecondary enrollments.

4. Whether attendance value-added correlates to students’ perceptions of key facets of high school culture and climate, such as safety.

To tackle these questions, we reached out to Jing Liu, assistant professor of education at the University of Maryland and the author of numerous studies on the causes and effects of student absenteeism. He leveraged sixteen years of administrative data (2002–03 to 2017–18) from a large and demographically diverse district in California whose attendance information included data on partial-day absences. It’s worth your time to read this (fairly short) study and Jing’s policy implications, but for those in a rush, here are the four key findings:

1. Conventional student absenteeism measures tell us almost nothing about a high school’s impact on students’ attendance.

2. Like test-based value-added, attendance value-added varies widely between schools and is highly stable over time.

3. There is suggestive evidence that attendance value-added and test-based value-added capture different dimensions of school quality.

4. Attendance value-added is positively correlated with students’ perceptions of school climate—in particular, with the belief that school is safe and behavioral expectations are clear.

There’s much to unpack here, but to us, four takeaways merit attention.

First, more information is better.

The message from this study isn’t that schools need to stop reporting raw attendance rates and chronic absenteeism. Instead, we think a both/and rather than either/or approach is the right choice. In fact, we’d go so far as to suggest that, just as some states have two grades for schools based on test scores (one for achievement and one for growth), we should consider having two measures of attendance (chronic absenteeism and “value-added” measures, once they’re vetted).[7]

In general, status measures and growth measures are apples and oranges, so it doesn’t make sense to average or aggregate them. The simplicity and usefulness of a single, summative grade is lost if it doesn’t serve any one purpose well.

For instance, if the purpose is to decide whether to renew a school’s charter for the next five years, that decision should rest on growth-based test-score measures. But if the purpose is to understand whether students are ready for college and career, status-based measures are best. Each tell us something different. So it is with chronic-absenteeism rates and attendance value-added.

Second, better attendance measures have real-world implications for educators.

One of the reasons for measuring a school’s impact on attendance is to be able to hold school staff accountable for what’s under their control. Plus, we want to encourage behavior that will make it likelier that students will come to school so they can learn more. “Value-added” measures are the best way to do that. They help us gauge how well teachers and school leaders cultivate better attendance because they adjust for what teachers and principals can’t influence, such as students’ demographics, baseline achievement, and prior absences and suspensions. Without making these adjustments, a chronic-absenteeism rating (based on raw attendance) might make a high-poverty school look bad, even if it’s actually high performing. Simply put, attendance value-added differentiates between high-poverty schools that deserve to be lauded and those that demand intervention.

Likewise, we need to worry about demotivating the teachers and principals who choose to work in high-poverty schools and may be getting unfairly penalized when, in reality, they are making progress in improving student attendance, even if the “status” measures remain unsatisfactory.

All that said, this study is the first to explore the feasibility of attendance value-added, and we need other researchers to test the measure empirically—with larger samples and in other states—before it’s ready for prime time. What’s more, though the study undoubtedly demonstrates the promise of attendance value-added, it also underscores the strength and utility of test-based value-added measures—and why we’d be foolish to move away from them.

Third, better attendance measures could help students and families make better decisions.

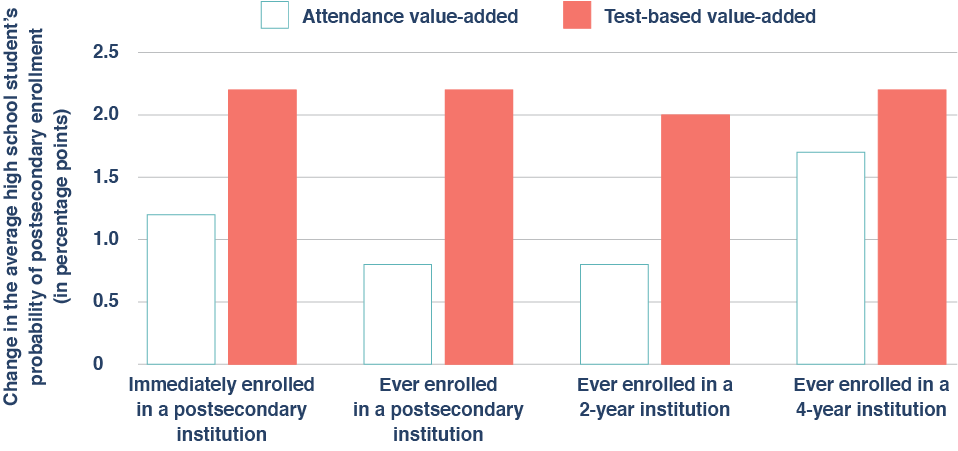

On average, attending a high school with high attendance value-added increases a student’s attendance by twenty-eight class periods (or roughly four school days) per year. And there is suggestive evidence that high schools that do an above-average job of boosting attendance also boost postsecondary enrollment—even if the school’s test-based value-added is middling.

That is to say, just as there are high-test-value-added, low-achievement schools that help students succeed, there are high-attendance-value-added, low-raw-attendance schools that do, too.

Many low-income parents face a choice between two schools with similar achievement and attendance patterns but with value-added scores that vary widely. Helping them to understand and act upon those distinctions is essential. We want parents to choose schools that are “beating the odds,” and value-added measures are one good way to identify these schools.

Finally, school safety matters when it comes to student attendance.

With wonky empirical studies such as this one, practitioners understandably ask, “What do these study findings imply for my work in real schools and classrooms?”

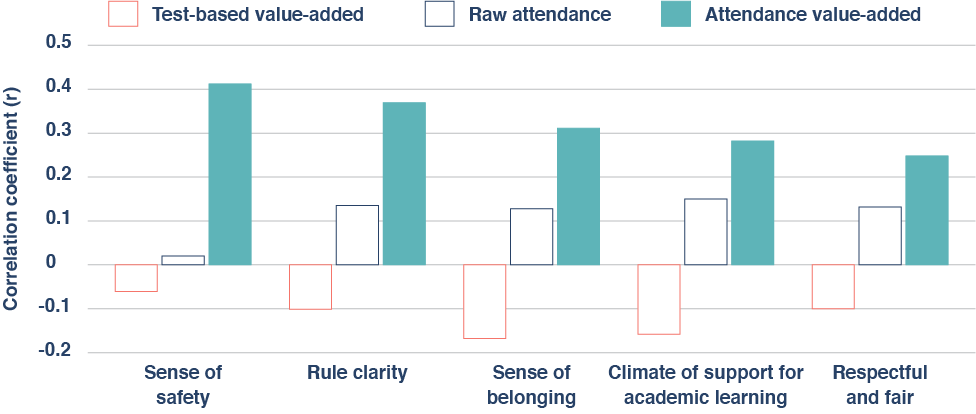

Although we hesitate to rely too heavily on correlational evidence, we’d point to some intriguing student-survey data. They consistently show that the strongest links to attendance value-added pertain to students’ sense of safety at school and their perception that the rules and behavioral expectations are clear.

In other words, staff who earnestly want to improve attendance rates should be mindful that safe schools and coming to school go hand in hand.

*************

To repeat, one in four American students was chronically absent in 2020, up from the previous rate of one out of six in 2017–18.[8] Thankfully, buildings reopened last year as educators learned to navigate the pandemic. But it’s past time to get all our kids back in school.

Cultivating a positive school culture—one that prioritizes student engagement, safety, and high expectations—has been and always will be a key piece of the attendance puzzle. But so is developing a novel way to isolate and measure a school’s impact on attendance so that the efforts (or lack thereof) of those who work there can be made visible.

That’s important because better measures can inform strategies to deter those absences in the first place.

It’s no secret that kids who aren’t in school don’t learn as much. Everyday experience and systematic research suggest that student absenteeism negatively impacts both short-run academic achievement and long-run outcomes such as high school graduation and college enrollment.[9] “Chronic absenteeism,” commonly defined as missing at least 10 percent of a school year (or about eighteen days), is widely accepted as a leading indicator of academic peril. At least thirty states and the District of Columbia have adopted student absenteeism, chronic absenteeism, or variants thereof as a “measure of school quality” under the Every Student Succeeds Act.

Yet, despite the central role that student absenteeism plays in educational effectiveness and policy, little is known about the extent to which schools actually influence students’ attendance (or the likely academic benefits of enrolling in a school that succeeds on this front). Recent studies have found that individual teachers can have a significant effect on student attendance.[10] But it’s likely that schools also impact attendance through mechanisms such as creating a culture of attendance, connecting with parents, and ensuring students’ physical safety, despite the fact that some principal determinants of a schools’ attendance rate—such as students’ home lives, access to transportation, and physical health—are largely beyond the control of educators.

As American education slowly emerges from yet another Covid-induced wave of school closures and quarantines, the need to understand how and why schools affect student attendance has never been greater. Accordingly, this study breaks new ground by using a value-added framework to examine high schools’ contributions to attendance after accounting for individual students’ prior attendance rates and other observable characteristics. In other words, it seeks to gauge schools’ “attendance value-added.”

With test-based value-added as a reference point, the study also evaluates the validity of this new indicator of school quality by quantifying its stability, impacts on short-term and long-term outcomes, and links to students’ perceptions of school climate.

Specifically, the study answers the following research questions:

1. To what extent do conventional measures of student absenteeism reflect high school students’ individual characteristics as opposed to high schools’ effects on attendance?

2. To what extent do high schools vary in their “attendance value-added”? And how much does a typical high school’s attendance value-added vary over time?

3. How strongly correlated are test-based and attendance value-added? And how well do each of these measures predict long-run outcomes such as postsecondary enrollment?

4. How strongly does attendance value-added correlate to students’ perceptions of various dimensions of high school culture and climate (e.g., safety)?

Like its test scores, a school’s raw attendance rate often reflects the challenges its students face outside of school rather what happens within it. For example, a number of studies have found that minority, low-income, and low-achieving students accrue more absences than their White, high-income, and high-achieving peers.[11] Thus, if the goal is to hold schools accountable for what’s under their control—and shine a light on those that succeed in promoting attendance—it is critical to account for students’ demographics and educational histories.

One previous study evaluated school performance by using absenteeism (along with many other non-test-score student outcomes) using a value-added framework;[12] however, it focused on full-day absenteeism, meaning that it failed to capture partial-day absenteeism (e.g., coming to school on time but skipping sixth period), which other research suggests accounts for at least half of lost instructional time at the secondary level.[13] Failing to account for these additional absences could lead to biased estimates of schools’ impacts, especially when partial-day absenteeism is more prevalent in some schools than others. Hence the present study’s focus on the total number of classes that a student misses rather than the total number of days that he or she is absent (or his or her chronic-absenteeism status).

Test-based value-added, which is a well-established measure of school quality, is a useful benchmark for “attendance value-added” insofar as it helps us understand whether the latter provides similarly useful information. And linking both measures to students’ long-run outcomes can help unpack the complex mechanisms through which schools contribute to student success.

This study uses sixteen years of administrative data (2002–03 to 2017–18) from a large and demographically diverse urban school district in California that serves approximately 60,000 students each year.[14] This dataset is unique in that it contains student attendance records for each class, allowing for a highly precise measure of student absenteeism.[15] It also includes detailed information on students’ gender, race/ethnicity, special-education status, English-language-learner status, discipline histories, math and English language arts (ELA) test scores, grade point average (GPA), and residential addresses (which enable the derivation of neighborhood characteristics)—plus several long-term outcomes, including measures of college enrollment (collected from the National Student Clearinghouse).

Three years of student self-reported school culture and climate survey data (for 2015–16 to 2017–18) are used to examine the associations between attendance value-added and various dimensions of school climate. The survey contains four main constructs, including “climate of support for academic learning,” “sense of belonging,” “knowledge and fairness of discipline rules and norms,” and “sense of safety”; however, for the purposes of this analysis, the two subconstructs that comprise the “knowledge and fairness of discipline rules and norms” constructs (“Rule Clarity” and “Respectful and Fair”) are analyzed separately (for a detailed description of the survey items, see Appendix C in the PDF).

The analytic sample includes 58,125 ninth-grade students[16] who attended a total of twenty regular high schools between 2002–03 and 2017–18.[17] Of the students in this group, 50 percent were Asian, 23 percent were Hispanic, 11 percent were Black, and 9 percent were White. On average, students missed seventy-nine class periods annually or roughly eleven school days (for more descriptive statistics, see Table B1 in the PDF).

A high school’s attendance value-added is constructed based on the total number of class periods that its school’s ninth graders missed in a given school year. To isolate a high school’s contribution to ninth-grade attendance in a given school year, the model controls for a rich set of student demographics and prior outcomes, including gender, age, race/ethnicity, English-language-learner status, special-education status, neighborhood conditions, prior achievement, prior suspensions, and prior absences, as well as time-varying school-level covariates that correspond to the individual-level covariates. To avoid mechanical endogeneity in the long-run analysis, we use “leave-year-out” estimates which give additional weight to value-added attendance in more recent years for a given school, and a weighting method to account for the “drift” of school effects (meaning they might fluctuate over time).

We estimate test-based value-added scores using essentially the same methodology. To make attendance- and test-based value-added scores commensurable, both variables were standardized, and attendance value-added was reverse coded (for more technical details, see Appendix A in the PDF).

Finding 1: Conventional student-absenteeism measures tell us almost nothing about a high school’s impact on students’ attendance.

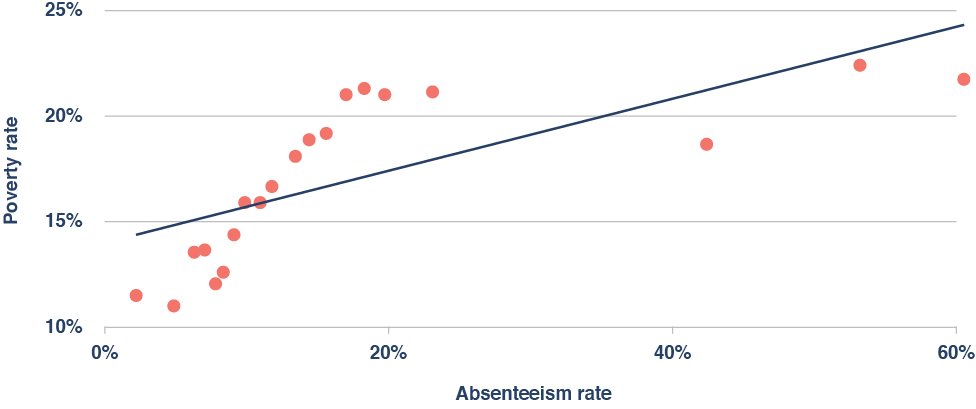

On average, high schools that serve large proportions of low-income students have much higher absenteeism and chronic-absenteeism rates than those that serve more affluent students (Figure 1). And a similar pattern also emerges for other demographic characteristics, such as the percentage of students who are White, Black, or Hispanic (see Appendix B, Table B2 in the PDF).

Figure 1. On average, high-poverty schools have much higher rates of absenteeism.

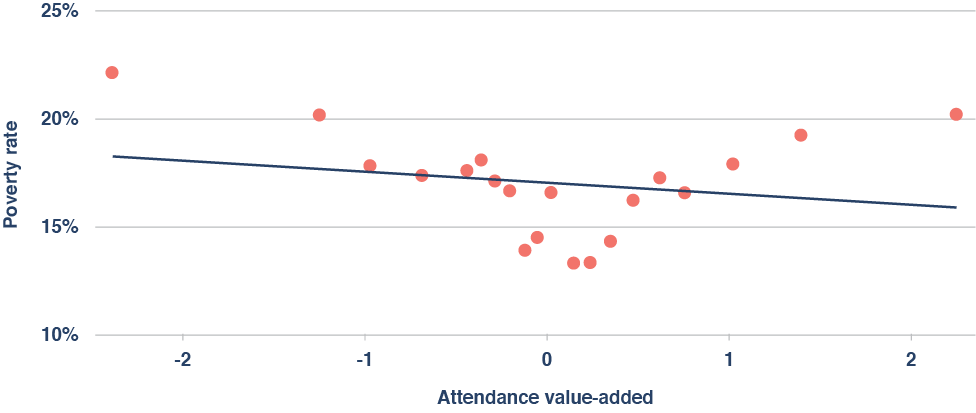

In contrast, because “attendance value-added” takes students’ demographic characteristics and attendance histories into account, it isn’t significantly correlated with a school’s poverty rate (Figure 2), nor is it significantly correlated with most other demographic characteristics of high schools (see Appendix B, Table B2 in the PDF).

Figure 2. There is no significant relationship between a school’s poverty rate and its attendance value-added.

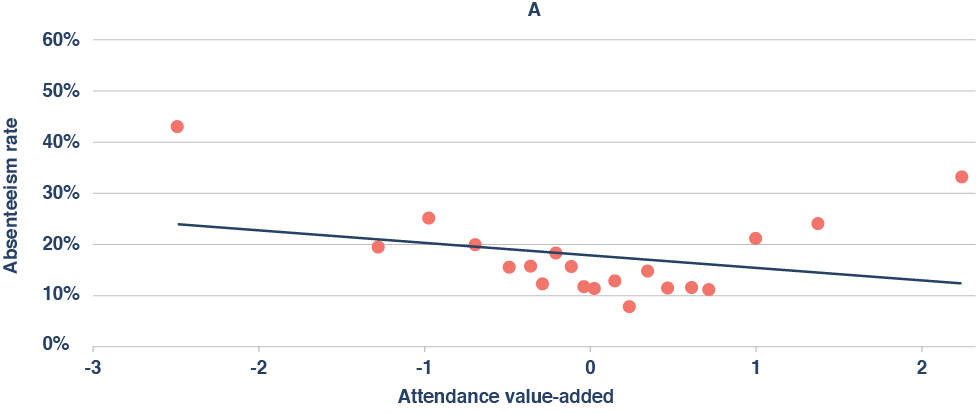

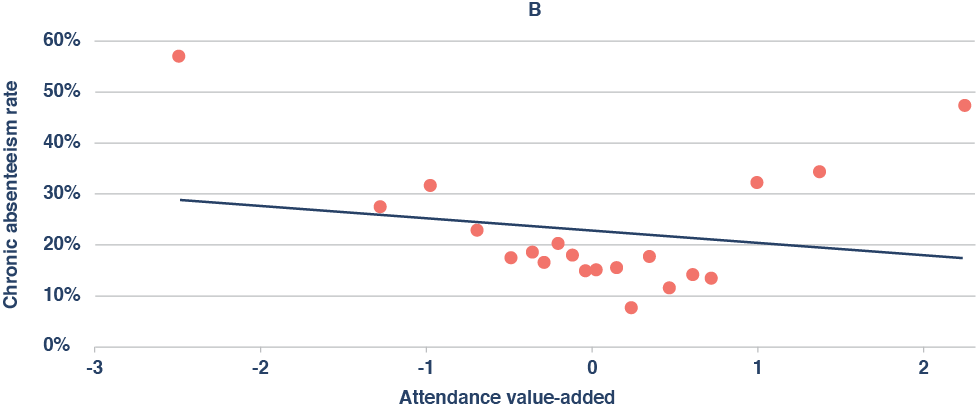

Finally, the correlation between a school’s attendance value-added and its overall absenteeism rate is quite small, as is the correlation between a school’s attendance value-added and its chronic-absenteeism rate (Figure 3A-B).

Figure 3A-B. Conventional absenteeism measures tell us almost nothing about a school’s effects on attendance.

In other words, conventional absenteeism measures tell policymakers almost nothing about a high school’s effect on attendance. So if the goal is to hold schools accountable for things that are under their control, these measures are both uninformative and unfair to high-poverty schools—just like raw proficiency rates and other test-based measures that fail to capture a school’s value-added.

Finding 2: Like test-based value-added, attendance value-added varies widely between schools and is highly stable over time.

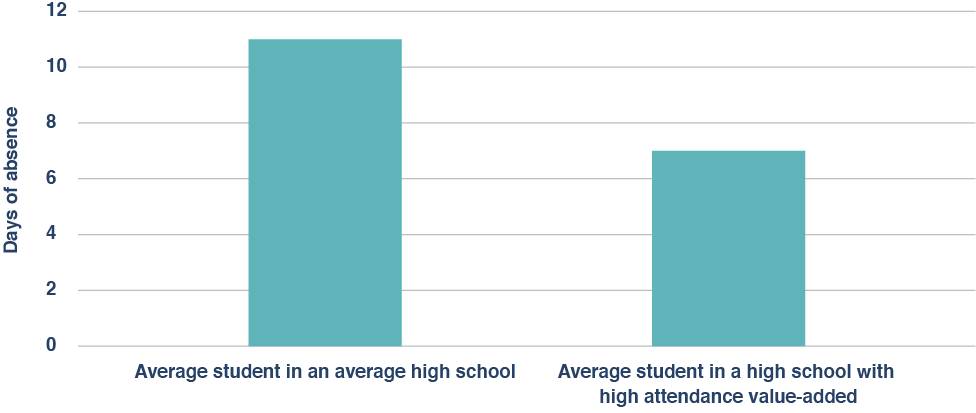

On average, attending a high school with high attendance value-added increases a student’s attendance by twenty-eight class periods (or roughly four school days) per year (Figure 4). Relative to the variation in attendance and achievement that is observed at the student level, the magnitude of this effect is somewhat larger than the magnitude of an above-average school’s effect on its students’ ELA and math test scores.

Figure 4. Attending a high school with high attendance value-added significantly reduces the average student’s absenteeism rate.

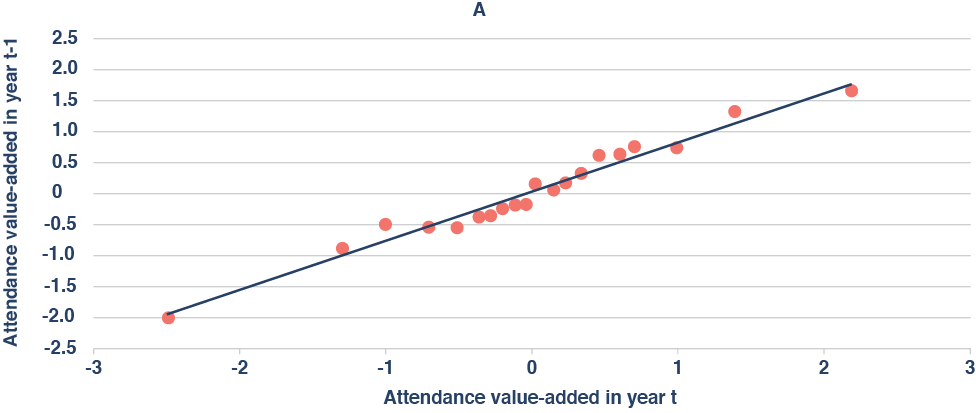

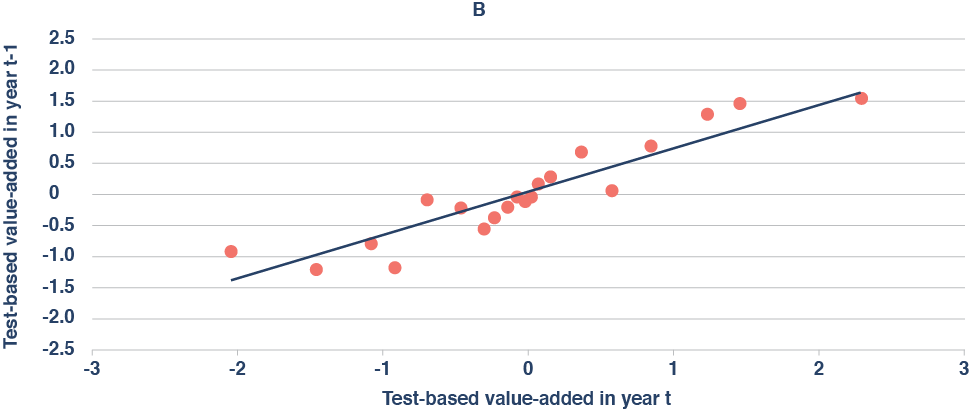

Similarly, the average correlation between a school’s attendance value-added in one year and its attendance value-added in the following year is 0.878, while the year-to-year correlation for test-based value-added is 0.774. In other words, attendance value-added is actually more stable than test-based value-added (Figure 5A-B).

Figure 5A-B. Attendance value-added exhibits even greater year-to-year stability than test-based value-added.

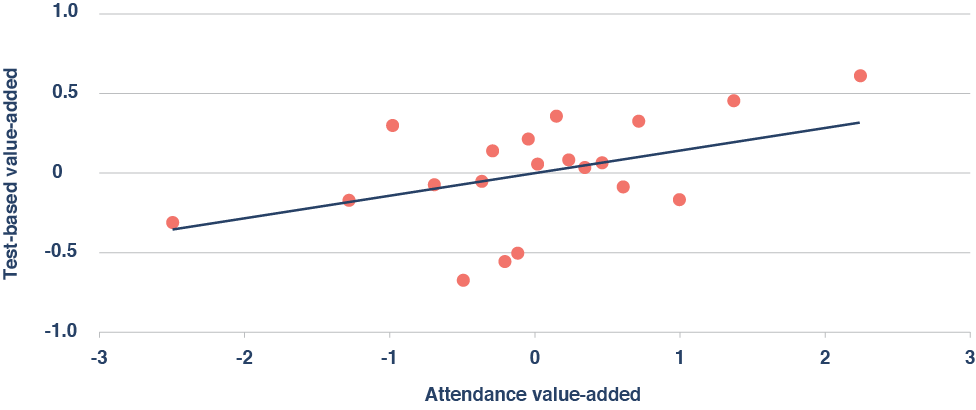

Finding 3: There is suggestive evidence that attendance value-added and test-based value-added capture different dimensions of school quality.

Perhaps surprisingly, attendance value-added is weakly correlated with test-based value-added at the school level (Figure 6). Moreover, each of these measures is only predictive over its own domain: that is, attendance value-added offers no additional information about a school’s impact on student achievement conditional on test-based value-added, and test-based value-added offers no additional information about a school’s impact on attendance conditional on attendance value-added (see Appendix, Table B4 in the PDF).

Figure 6. Attendance value-added is weakly correlated with test-based value-added.

In addition to this disconnect, there is also suggestive evidence that high schools with above-average attendance value-added boost postsecondary enrollment—even if their test-based value-added is average (Figure 7). For example, there is suggestive evidence that attending a high school with high attendance value-added increases a ninth grader’s probability of attending a four-year college by 1.7 percentage points (for context, attending a high school with high test-based value-added but average attendance value-added boosts four-year college attendance by 2.2 percentage points).

Figure 7. Evidence suggests that attending a high school with high attendance value-added boosts postsecondary enrollment.

Collectively, these results suggest that attendance value-added captures some dimensions of school quality that are not captured by test-based value-added; however, additional research (with larger samples) is needed to clarify this point and to establish more conclusively that attendance value-added significantly predicts long-term outcomes.

Finding 4: Attendance value-added is positively correlated with students’ perceptions of school climate—and, in particular, with the belief that school is safe and behavioral expectations are clear.

Of the five aspects of school climate that are included in the district’s school-climate survey, attendance value-added is most strongly correlated with the sense of safety that students feel at school and the clarity of rules and expectations related to student behavior—though it’s also significantly correlated with students’ sense of belonging, their perceptions of academic support, and their belief that student-adult relationships are respectful. In contrast, neither test-based value-added nor a school’s raw absenteeism rate (i.e., the total number of classes missed by the average student) is significantly correlated with any of the five constructs reported by students (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Unlike test-based value-added and raw attendance, attendance value-added is significantly correlated with several dimensions of school climate.

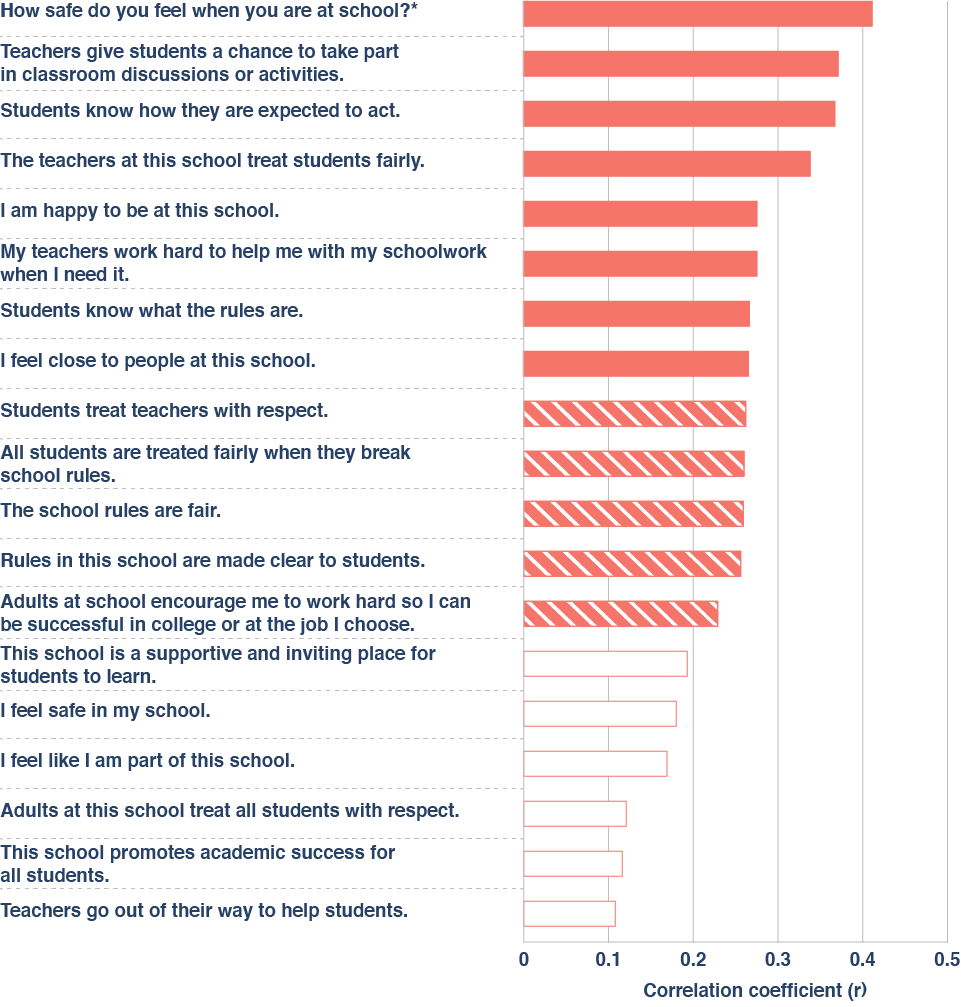

At a more granular level, attendance value-added has meaningful correlations with several individual survey items touching on various aspects of school climate, including the perception that “teachers give students a chance to take part in classroom discussions” and that “the teachers at this school treat students fairly”; however, the single item that correlates most strongly to attendance value-added is, again, students’ feelings of safety (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Attendance value-added is significantly correlated with a diverse collection of individual survey items.

1. Using raw student-absenteeism measures in accountability systems likely imparts credit or penalty to schools that don’t deserve it.

As the findings make clear, some schools do a better job of getting students to come to class regularly. Yet many of these schools are overlooked by states’ existing accountability systems—even as others are rewarded for habits and circumstances that students developed before their arrival. To be clear, there are good reasons to report schools’ raw attendance and chronic-absenteeism rates, which are transparent, parent-friendly, and crucial to understanding the depth of the problem. But if the goal is to hold schools or educators accountable for things they can control or help parents understand if their child’s attendance is likely to improve, then raw attendance rates are unfair and uninformative (and the same is also true of any non-test-based indicator that fails to account for the things students bring to school).

2. States and districts with the requisite resources should explore “attendance value-added” measures to better understand schools’ and teachers’ effects on attendance.

Per the findings, there is suggestive evidence that students see long-term benefits from attending high schools with high attendance value-added, even if their raw attendance rates, test scores, and test-based value-added are average. Broadly speaking, this evidence is consistent with an emerging literature that suggests that effective schools contribute to students’ success through the cultivation of noncognitive and/or socioemotional as well as academic skills.[18] Accordingly, states and other jurisdictions should consider developing their own measures of attendance value-added. That will, of course, entail the collection of precise and detailed attendance data while minimizing the potential for gaming and misreporting.

3. Schools and districts that are seeking to boost their attendance rates in the wake of the pandemic should remember that many students prioritize safety and order.

It is notable that the strongest correlates of “attendance value-added” at the high school level are students’ feelings of safety and order—or, more specifically, their sense that rules and behavioral expectations are clear—consistent with prior research on school climate[19] (for example, 7 percent of Black teens report avoiding school activities or classes because of “fear of attack or harm”).[20] Meanwhile, surveys of educators suggest that student absences have doubled as a result of remote learning and have remained elevated, along with various forms of misbehavior—even as students have returned to in-person instruction.[21] As they continue to do so, policymakers and educators must continue to focus on reengaging students, ensuring that school is a safe place, and combating the sadly rejuvenated scourge of chronic absenteeism. Left unaddressed, its implications for American youth and society are troubling indeed.

***To read the appendices, click “DOWNLOAD PDF”.***

[1] Jennifer Darling-Aduana, et al., “Learning-Mode Choice, Student Engagement, and Achievement Growth During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” EdWorkingPaper No. 22-536, Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, https://www.edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/ai22-536.pdf

[2] U.S. Department of Education, “Supporting Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Maximizing In-Person Learning and Implementing Effective Practices for Students in Quarantine and Isolation,” accessed March 8, 2022, https://www.ed.gov/coronavirus/supporting-students-during-covid-19-pandemic; Lucrecia Santibanez and Cassandra Guarino, “The Effects of Absenteeism on Cognitive and Social-Emotional Outcomes: Lessons for COVID-19,” EdWorkingPaper No. 20-261, Annenberg Institute for School Reform at Brown University, October 1, 2020, https://edworkingpapers.com/sites/default/files/Annenberg%20WP%20Submission%20-%2020201001_0.pdf; Carl Smith, “Chronic Absenteeism Is a Huge School Problem. Can Data Help?” Governing: The Future of States and Localities, May 20, 2021, https://www.governing.com/now/chronic-absenteeism-is-a-huge-school-problem-can-data-help; and Scott Calvert and Ben Chapman, “Schools See Big Drop in Attendance as Students Stay Away, Citing Covid-19,” Wall Street Journal, January 12, 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/schools-see-big-drop-in-attendance-as-students-stay-away-citing-covid-19-11641988802.

[3] Matt Barnum, “Schools are back in person, but quarantines, health concerns have students missing more class,” Chalkbeat, December 1, 2021, https://www.chalkbeat.org/2021/12/1/22811872/school-attendance-covid-quarantines.

[4] Sherri Doughty et al., K-12 Education: An Estimated 1.1 Million Teachers Nationwide Had At Least One Student Who Never Showed Up for Class in the 2020-21 School Year (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Accountability Office, March 23, 2022), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-22-104581.pdf; Ted Oberg and Sarah Rafique, “‘Daunting task’ to locate students as thousands are still missing from Houston-area schools,” Ted Oberg Investigates, ABC 13 Eyewitness News, August 12, 2021, https://abc13.com/students-missing-unenrolled-houston-isd-enrollment-drop/10945181; Tareena Musaddiq et al., “The Pandemic’s Effect on Demand for Public Schools, Homeschooling, and Private Schools,” Working Paper 2021 (Ann Arbor, MI: Education Policy Initiative; Boston, MA: Wheelock Education Policy Center, September 2021) https://edpolicy.umich.edu/sites/epi/files/2021-09/Pandemics%20Effect%20Demand%20Public%20Schools%20Working%20Paper%20Final%20%281%29.pdf.

[5] Hedy N. Chang and Mariajosé Romero, Present, Engaged, and Accounted For: The Critical Importance of Addressing Chronic Absence in the Early Grades (New York, NY: National Center for Children in Poverty, September 2008), http://www.nccp.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/text_837.pdf.

[6] Camille R. Whitney and Jing Liu, “What We’re Missing: A Descriptive Analysis of Part-Day Absenteeism in Secondary School,” AERA Open 3, no. 2 (2017): 1–17, doi:10.1177/2332858417703660.

[7] Chester E. Finn, Jr., and Chad L. Aldis, “Disputing Mike and Aaron on ESSA school ratings,” Flypaper, Thomas B. Fordham Institute, October 17, 2016, https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/commentary/disputing-mike-and-aaron-essa-school-ratings.

[8] Attendance Works, “National Analysis Shows Students Experiencing Chronic Absence Prior to Pandemic Likely to be Among the Hardest Hit by Learning Loss,” news release, February 2, 2021, https://www.attendanceworks.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Attendance_Works_OCR_17-18_Press_Release_020121.pdf.

[9] Jing Liu, Monica Lee, and Seth Gershenson, “The short-and long-run impacts of secondary school absences,” Journal of Public Economics 199 (2021): 104441, doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104441.

[10] Jing Liu and Susanna Loeb, “Engaging teachers: Measuring the impact of teachers on student attendance in secondary school,” Journal of Human Resources 56, no. 2 (2019): 343–79, doi:10.3368/jhr.56.2.1216-8430R3.

[11] Michael A.Gottfried and Ethan L. Hutt, eds., Absent from School: Understanding and Addressing Student Absenteeism (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press, 2019).

[12] C. Kirabo Jackson, et al., “School effects on socioemotional development, school-based arrests, and educational attainment,” American Economic Review: Insights 2, no. 4 (2020): 491–508.

[13] Camille R. Whitney and Jing Liu, “What we’re missing: A descriptive analysis of part-day absenteeism in secondary school,” AERA Open 3, no. 2 (2017): 2332858417703660, doi:10.1177/2332858417703660.

[14] At the suggestion of district leaders, we exclude data from 2013–14, when the district’s transition to a new attendance-tracking system caused some data-quality issues.

[15] Before the school year 2013–14, teachers used a paper scantron to mark a student as absent, tardy, or present in each class; however, starting in 2014–15, the district transitioned to an electronic system called Synergy in which teachers use an electronic tablet to track each student’s class-attendance information in real time. Conversations with several district leaders suggest that data quality in the transition year (2014–15) was low due to the rolling out of the new system. Accordingly, that school year is omitted when estimating school value-added to attendance.

[16] To ensure that each school in the sample has enough observations for both cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis, schools that have fewer than five years of data, and school years that have fewer than ten students are dropped.

[17] Because they serve a very different population of students, the special-education schools in the district are not included in the analysis.

[18] Jackson, “School effects on socioemotional development.”

[19] Susan Williams, et al., “Student’s perceptions of school safety: It is not just about being bullied,” The Journal of School Nursing 34, no. 4 (2018): 319–30, doi:10.1177/1059840518761792.

[20] “Students’ reports of avoiding school activities or classes or specific places in schools,” National Center for Education Statistics, accessed February 19, 2022, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/a17.

[21] Mark Lieberman, “5 things you need to know about student absences during COVID-19,” Education Week, October 16, 2020, https://www.edweek.org/leadership/5-things-you-need-to-know-about-student-absences-during-covid-19/2020/10.

This report was made possible through the generous support of the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, as well as our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. We are deeply grateful to external reviewers Cory Koedel, professor of economics and public policy at the University of Missouri, and Douglas Harris, professor of economics at Tulane University, for offering feedback on the methodology and draft report.

On the Fordham side, we express gratitude to associate director of research, David Griffith, for managing the study, asking probing questions, and editing the report. Thanks also to Chester E. Finn, Jr. for providing feedback on drafts, Pedro Enamorado for managing report production and design, Victoria McDougald for overseeing media dissemination, and Will Rost for handling funder communications. Finally, kudos to Pamela Tatz for copyediting and Dave Williams for creating the report’s figures.

Cover Photo: smolaw11/iStock/Getty Images Plus

On this week’s Education Gadfly Show podcast (listen on Apple Podcasts and Spotify), Paul Hill, founder of the Center on Reinventing Public Education and emeritus professor at the University of Washington Bothell, joins Mike Petrilli and Checker Finn to debate recent reform setbacks in Denver, and whether they prove that portfolio districts are doomed. Then, on the Research Minute, Amber Northern shares good news from a study examining the intersection of gifted education and segregation.

Recommended content:

Feedback welcome!

Have ideas or feedback on our podcast? Send them to our podcast producer Pedro Enamorado at [email protected].

Cheers

Jeers