An open letter to my ed school dean

By Robert Pondiscio

By Robert Pondiscio

Last month, Emily Hanford of American Public Media filed a withering indictment of reading instruction in U.S. schools. Her radio documentary, “Hard Words,” exposed how much “decades of scientific research” have taught us about reading—and how little of it has reached classroom practice via teacher training. Her conclusion was simple and unsparing: “Schools aren’t teaching reading in ways that line up with the science.”

Hanford is echoing arguments that have been made by a generation of researchers and advocates, but timing is everything: I can’t recall a similar reaction to any other recent piece about classroom practice. And it has legs. It’s been a month since the documentary was posted, but I’m still seeing teachers sharing and discussing it on social media daily. One such response, posted to the Facebook page of Decoding Dyslexia-Arkansas, was a letter from teacher Patricia C. James to the dean of the Arkansas State University, where she graduated with a double major in Elementary Education and Special Education. James wrote that, while her teacher preparation was mostly very good, she was “totally unprepared to teach reading, especially to the struggling readers that I had at the beginning of my career in my resource classroom.”

“Having been taught phonics in elementary school, I knew my students needed more than the Balanced Literacy ‘3 cueing strategy’ that basically encourages students to guess unknown words,” James wrote. “Reading should not be a ‘guessing game,’ which is exactly what Balanced Literacy and Whole Language reduces it to.”

Another educator, Susan L. Hall, the CEO of the 95% group, an educational consulting company, posted a link to James’s letter on Twitter and wondered what might happen if every teacher who felt ill-prepared to teach reading wrote a similar letter to their ed school deans. I second the motion and hope others will do the same.

Here’s my letter to the current dean of my ed school.

***

Dear Dean Rose Rudnitski:

On a shelf, three feet from my elbow, is my diploma from Mercy College, awarding me the lordly title of “Master of Science, Elementary Education.” It’s hard to look at it without wincing a bit. I mastered no effective literacy practices in the two years I spent in the “New Teacher Residency Program,” a program designed specifically for the New York City Teaching Fellows, the alternate certification program I joined in the summer of 2002. Nor was there very much “science” in my coursework. I’m grateful for the professional credential, which allowed me to enter the teaching profession. But if there’s anything one might expect an advanced degree in elementary education to include, it would be teaching reading. It wasn’t part of my program.

There is a science of reading and we owe it to all future elementary school teachers that it be taught and embraced so that it might improve outcomes for children. In his recent book Language at the Speed of Sight, cognitive neuroscientist Mark Seidenberg makes a pointed and persuasive case that “the principal function of schools of education is to socialize prospective teachers into an ideology—a set of beliefs and attitudes.” There is a radical difference between what he derides as the “culture of education” and science. The two have “different goals and values, ways of teaching new practitioners, and criteria for evaluating progress,” Seidenberg writes.

It’s hard not to agree. Last weekend, I dug out the thick portfolio of papers, written reflections, and student work samples that members of my cohort were required to collect and curate as indicators of the learning outcomes our masters program demanded. To earn my degree, I had to demonstrate my “passionate commitment to learning” and show proof that I was a “reflective practitioner.” Teaching the “whole child” required me to show that I teach “responsively” and “in context,” but there’s no visible evidence, in my portfolio or in my memory, that suggests any attention to psychology, cognitive science, language development, or the rich body of research in those fields that might shape our views of teaching and learning.

Indeed, if someone unfamiliar with our field had only my portfolio as evidence, they might conclude that the most important challenge a new teacher faces is not learning and mastering a body of professional knowledge or demonstrating skill as a practitioner, the hallmarks of a true profession like medicine or the law. They would likely assume that the key to classroom success is developing a “personal philosophical vision” of education—another of the essential outcomes I was required to articulate to earn my masters degree.

Emily Hanford’s radio documentary focused on the efforts of a school district in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, to diagnose and reverse the rampant reading failure in the district—and not just among low-income kids. “When chief academic officer Jack Silva was examining the reading scores, he saw there were plenty of kids at the wealthier schools not reading very well either,” Hanford reported. “This was not just poverty. Since he knew nothing about reading, he started searching online.” Dwell for a moment on that anecdote and what it portends. When the CAO of a school district, someone in a position of expertise and authority in an American school system, is in the dark about effective reading practice and has to Google it, it’s says something unsettling and alarming about the lack of a common professional knowledge base in our field. Ultimately Hanford’s documentary traces much of our failure not to teachers, but those who prepare us—or fail to. “Why aren’t kids being taught to read?” she asks. “Too many teachers, school administrators, and college professors don't know the science,” Hanford concludes. It’s cold comfort to know that my teacher preparation program at Mercy College—long on my development as a “reflective practitioner,” short on effective practice—was not anomalous. But that did not help my South Bronx fifth graders.

I don’t wish to be unkind. I remain deeply grateful for the efforts of my Mercy College instructors and mentors. Rereading many of the dozens of “moments that matter” reflection pieces I wrote in my first two years in the classroom are plaintive; some are nearly despairing. I’m impressed in retrospect at the humane and empathetic tone of the many and extensive handwritten comments on those papers. But I cannot help but wish that less attention had been paid to the development of my “philosophical vision” and willingness to “explore one’s deepest beliefs about teaching.” This is the language of ideology and religion, not the professional practice of a field grounded in science and research. It’s not what I needed to be effective. It’s not what my students needed from me.

Sincerely,

Robert Pondiscio

Editor’s note: Last week, leaders from many of the nation’s leading education reform organizations gathered in New Orleans for the twelfth annual Policy Innovators in Education Network conference. Louisiana’s State Superintendent of Education, John White, gave the keynote remarks. Here they are, edited slightly for readability.

Louisiana is a state that still bears very deep scars of the most horrific conditions that were perpetrated on behalf of nearly half of its population for centuries: enslavement, segregation, institutional racism. It’s a state that is digging itself very visibly out of a nineteenth-century economy and scraping to get into a twentieth- and twenty-first-century economy. Louisiana is a place of extraordinary assets, yet it’s also a place of tremendous struggle.

But the fact is, you can go into any corner in Louisiana today and you can see in its schools, in its Head Starts, in its childcare centers, in its vocational programs, and in its community colleges a level of professionalism, and a level of acumen, that would have been unimaginable here in the 1990s. Unimaginable in a state with schools that were not racially integrated forty years ago that you would see the level of professionalism, the skill, and the learning to standard that you see today in Louisiana’s classrooms. And that has become an accepted condition, and there is an accepted expectation of measurable learning gains in every classroom in this country. That is a tremendous victory.

There are tangible, quantifiable gains to be made, and we can look back on investments in federal, state, and local education policy to see the dividends that they have borne. Dividends in early literacy and graduation gains higher than ever before in this state, higher than ever before in this country. Even dividends in postsecondary education. We have a more college-educated population achieving higher things in our colleges and our postsecondary institutions in Louisiana and across our country than ever before. And there is a reason for that. It’s called education reform.

Education reform has made positive gains in this country for the people whom it’s set out to serve without question. And whereas, when I started out my career in the 1990s and people ask you, “Point me to a set of schools where large groups of students are beating the odds, and are achieving some semblance of hope in the American dream in spite of challenging conditions as a child,” you could count on your hand how many schools met those criteria. Today, there are hundreds of them. Education reform, largely thanks to the advocacy that you and your organizations have enacted, is to be thanked for that.

And yet for some reason, today we have a political climate in which—whatever side of the Common Core issue you are on, whatever your take on school vouchers, wherever you come out on standardized testing or what have you—you cannot question the fact that politicians are running from education and not toward it. They are running from our elementary schools, our middle schools, and our high schools. And where they are even remotely interested in our education, it is in thin solutions for our postsecondary education and thin solutions for early childhood education. Somehow it’s the thirteen years, the thirteen deeply formative years, of school that they seem to want nothing to do with.

The 2016 presidential election was evidence of this, during which there was an intellectually impoverished political agenda on both sides of the aisle regarding education. Doubtless the midterms will be that way, and doubtless that, if they continue on this course, the next presidential election will be the same. Our issue, unfortunately, has moved from being a front-page issue in New Orleans, in Baton Rouge, and in every one of your communities, to being at best a back-page issue—and one for which Republicans and Democrats alike see little political currency to be gained. And that is a serious, serious problem.

Because my hypothesis would be that the brilliance represented in this room and in your organizations is not actually in the extraordinary elegance of your ideas, it’s not in your ESSA plans, your accountability systems, how great your evaluation systems are, or your curriculums. It has very little to do with the actual policies. And it has to do with the fact that over two or three decades, some of the nations most committed, invigorated, finest people, rich and poor, from west and east, from all racial backgrounds, have actually come together to focus on public education, or publicly-funded education. They have brought tremendous and uncommon energy to this issue, Republicans, Democrats, and independents alike. And we have achieved the gains we have, not because we are smarter than everybody else, but because we have great people who saw this as an issue to which they wanted to dedicate their life.

But when governors and gubernatorial candidates run from our issue, when big city mayors run away from our issue, and most certainly when presidential candidates want nothing to do with our issue other than a couple of throwaway lines, how can you expect the next generation of people sitting in your chairs today to want to serve your organizations? To want to serve this issue in your communities? And I would posit that more than any crisis of accountability, more than any crisis of school choice, whether you like testing or not, whatever you think of teacher evaluation, or whatever your issue, that is the single biggest crisis facing education reform today: the relevance of our issue, and therefore the attractiveness of our issue, for the next generation of activists, advocates, philanthropists, and politicians. They will run to easier solutions with popular taglines because education is hard and because the tail of change is long unless great people work on the issue.

I used to think that I had answers to the problem that I am outlining. And I hope it is a problem that you share a sense of, but I don’t have great answers. I used to think that the answer was maybe in the biggest cities, like New York, Chicago, L.A., and D.C., taking up the mantle of reform there and putting it up on the front pages of the New York Times. I used to think that maybe the obstacle was us finding a better set of issues, moving off of the longstanding principles or topics that we have held so stringently, and finding value in things that offer more value to a more diverse audience. I also used to think that maybe it was about moving our focus away from places like New York, D.C. and San Francisco, where extraordinary wealth exists alongside extraordinary poverty, because that is an intoxicating combination that doesn’t exist in most parts of the country. Maybe we needed to spend more time in suburbs, and in secondary cities, and in rural communities. I used to think that it was some billionaire who could break us out of either being a choice advocate or being a systems advocate or being a kind of newness-for-newness’s-sake advocate, which is where I say the foundations are today. And now I am a little more modest and humble about it, and I don’t know if any of those are the answer. Maybe all of them are.

But I do know that, if we want more Bill Haslams, more Mike Bloombergs, more politicians who put all the noise to the side, who invent, who create newness, who expand opportunity in real ways, at great scale, in every corner of every jurisdiction, we have to change something. We have to reinvent. We have to be new. And I look forward to the discussions today because maybe we can begin to tease out a little bit of this. But I hope that, as you come together, you understand how rare of an opportunity this is, how rare it is for advocates to cross partisan lines and unite. And it shouldn’t just be an opportunity for an echo chamber about issues that are well tried. It should be an opportunity to think about how we remain relevant. How we remain on the front page. I believe it’s possible because the good news is, whether you are in New Orleans or New York or anywhere in this country, there is one force that we can harness, that no other issue can harness, and that is the love of Americans for their children. Everyone knows that children are our most precious assets, and therefore we have a tremendous platform from which to get advocates. But for some reason we are not converting that into attention, into political capital, and into new ideas. And that has to change.

John White is the Louisiana State Superintendent of Education.

Over the past decade, I’ve deepened my belief in the power of letting educators form non-profits to run public schools. Both experience (walking into amazing public schools) and research (a track record of reading and math gains) have shown me that non-profits are an incredibly valuable tool in making public education better.

I’ve also deepened my belief in unified enrollment systems. They can give families a lot of information about public schools and make enrolling in public schools much easier.

I do not have deep confidence in my views on accountability. I often find myself moving up and down the spectrum of: no accountability (just let parents choose), to accountability-lite (require testing, share this information, but don’t intervene), to accountability heavy (require testing, give schools letter grades, intervene in lowest performing schools).

I think reasonable arguments can be made for all three approaches.

Recent NWEA Research

NWEA just published a new report using a national data set from the tests they license to schools. Many schools we work with use these tests. I’m not expert enough in statistics to evaluate the reliability of their findings, but the report raised some important issues.

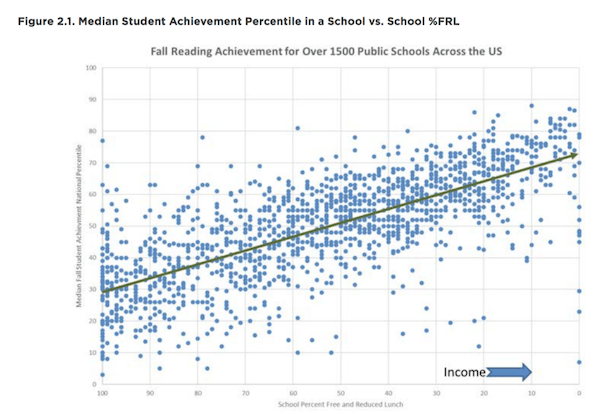

Absolute test scores are highly correlated with poverty. The chart below shows that test scores rise as income increases. This is not new information.

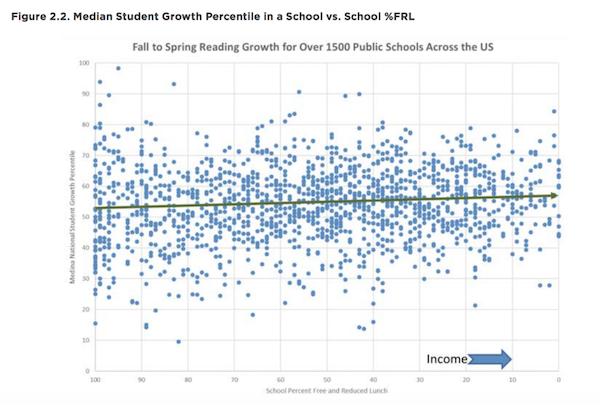

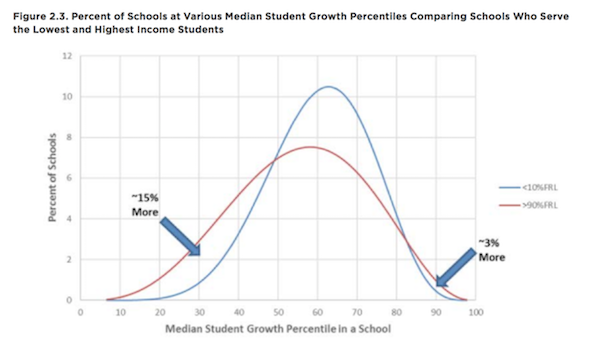

Student growth is not tightly correlated with poverty. Unlike absolute achievement, individual student growth does not rise significantly with income. Many high poverty achieve growth that mirrors those of their wealthier peers.

Schools with similar levels of poverty perform very differently on growth. The red line in the chart below represents how schools with high poverty perform on academic growth. It is a fairly wide curve. Many schools achieve low growth, while others achieve very high growth. To the extent you believe that growth is a pretty good measure of school performance (the researchers do), this performance spread might increase a policymaker’s willingness to intervene in low-performing schools and expand high-performing schools.

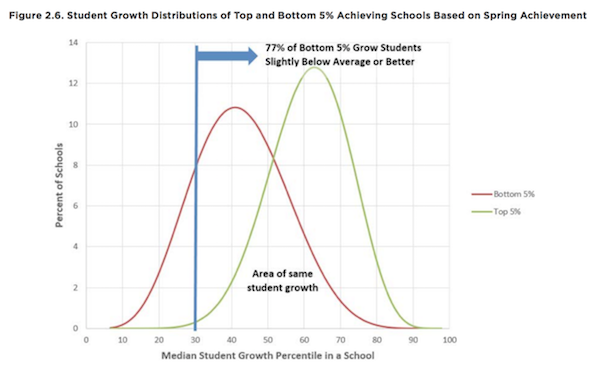

Focusing on absolute test scores will cause you to misidentify many, many schools. The graph below is tricky to read, but it’s very important. The red line represents all schools that are in the bottom 5 percent for absolute test scores. And it shows that 77 percent of these schools (the bottom 5 percent on absolute) are close to the average or better on growth. In other words, if you just closed the bottom 5 percent of schools based on absolute achievement, nearly 80 percent of the schools you’d close probably would be mistakenly closed (given their growth scores). This is pretty damning evidence against those who want to focus mostly on absolute achievement in accountability measures.

When does a good policy idea become indefensible because of bad practice?

Over the past few years, most states reworked their accountability systems during the reauthorization of No Child Left Behind.

Unfortunately, this report found that only eighteen states weighted growth for at least 50 percent of the total accountability score, with another twenty-three states weighting growth at least at 33 percent.

On one hand, this is an improvement over old accountability systems. On the other hand, this means a lot of states are unfairly rating high poverty schools that have decent growth but low absolute scores.

I think a fair critique of test-based accountability is that it’s a reasonable idea that has very little hope of being reasonably implemented.

My own thoughts

Again, I do believe deeply in letting non-profit organizations operate public schools. And I do believe deeply in enrollment systems that make it easier for families to find a great school for their children.

I’m uncertain about accountability, but here’s what I think I’d do if I were superintendent of a school district:

This type of accountability system gives parent’s good information, avoids the political war of giving low letter grades to schools with high absolute scores, and avoids the error of intervening in schools that have low absolute scores and higher growth scores.

It does give an accountability pass to schools with high absolute scores and low growth, but I view this as OK in that it’s both politically useful and it does reflect the notion that parents really want to get into these schools.

It also still uses test scores as the primary way to evaluate schools. This sits uneasy with me, as I think schooling is about much more than tests, but I haven’t seen any other way to measure schools that feels more reliable. I hope this changes.

I’m not very confident that this is the best system, but I think it’s the best of a bunch of options that all have reasonable drawbacks.

Another hard question would be what to do if local politics did not allow for the creation of a system like this. At some point, if the drumbeat for absolute scores was too much, I’d probably walk away from accountability as a superintendent.

But I’m not sure. If you scan my blog’s history, I’m sure you can find me saying conflicting things about accountability. I’m conflicted about it. But the above reflects my current thinking of what makes for a good accountability system. And as I wrote at the outset, reasonable arguments can be made for everything from no accountability to heavy-handed systems that require testing, give schools letter grades, and intervene in lowest performing schools. Nevertheless, research like NWEA’s recent study is worthwhile and helps shed further light on whether good policies are being implemented well.

Neerav Kingsland is the Managing Director of The City Fund. He first published this essay on his blog, “relinquishment.”

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the authors and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

A new study by Jason A. Grissom and Brendan Bartanen of Vanderbilt University examines the impact of principal effectiveness on teacher turnover. It’s well established that better school leadership leads to lower average turnover, but as the authors write, “all teacher turnover is not created equal.”

Grissom and Bartanen used data on all public education personnel in the state of Tennessee from 2012 to 2017. To gauge teacher effectiveness, they relied on observation and student growth scores. And for principals, they looked to evaluations by superiors, as well as surveys from teachers.

Tennessee’s statewide educator evaluation system, the Tennessee Educator Acceleration Model (TEAM) began in the 2011–12 school year and produced the data used in this study. This means that principals in Tennessee may have had better information to use when evaluating teachers than their peers in other states.

Grissom and Bartanen offer descriptive findings that add context to their examination of whether principals affect teacher turnover. Most noteworthy is that, in general, less effective teachers are more likely to turn over: 37 percent of the teachers in the least effective band turned over, compared to just 11 percent of teachers in the most effective range. Overall, 13 percent of teachers turned over each year.

As for the big question, the study echoes previous research, finding that principals with greater effectiveness have lower teacher turnover in their schools. Specifically, a 1 standard deviation (SD) increase in principal effectiveness is correlated with about a 5 percent change (0.5 percentage points) in teacher turnover.

Grissom and Bartanen also find evidence of “strategic retention,” wherein good principals are better at keeping effective teachers and getting rid of less effective teachers. A 1 SD increase in the superior rating (the superintendent’s rating of the principal) is associated with a 1.3 percentage-point decrease in turnover among teachers with comparatively high observation and student growth scores, and a 2.3 percentage-point increase in the likelihood of turnover among teachers with low marks. Their results also suggest that observation scores, rather than measures of teacher effectiveness derived from student test score growth, drive the patterns of strategic retention. This is in line with prior literature that says principals rely most on observation, and less on value-added measures because they’re opaque.

The effects Grissom and Bartanen detailed are strongest in suburban schools, perhaps because there’s more demand to teach in those areas. And indeed, if no one else wants to teach in your school, you probably shouldn’t be nudging teachers out. As the authors put it, “principals in more advantaged schools may worry less about finding quality replacements for teachers who leave, leading them to focus on pushing out low performers.”

The study’s findings are not exactly shocking. Good leaders at any kind of organization do the best with what they have, while also trying to improve their staff over time, hiring and promoting good people and sometimes nudging others towards the door. But it does demonstrate yet again that leadership matters.

SOURCE: Jason A. Grissom and Brendan Bartanen, “Strategic Retention: Principal Effectiveness and Teacher Turnover in Multiple-Measure Teacher Evaluation Systems,” American Educational Research Journal (September 2018).

If the purpose of school is to prepare students for adulthood, developing their financial literacy ought to be an important goal. So a new Brookings report by Matt Kasman, Benjamin Heuberger, and Ross A. Hammond examines what—if anything—states are doing to promote it. They find that forty include “substantive financial literacy material” in their standards, but that they “fall along a wide spectrum in terms of rigor.”

Part of the variance stems from the difficulty in defining “financial literacy.” Combining definitions from previous researchers, the authors present financial literacy as a dynamic relationship between five key components. A few of these are intuitive: foundational skills like basic math, knowledge of core financial concepts, and psychological factors such as confidence and self-control. The other two components, opportunities to interact with financial services and lasting behavioral impact, are rarely included in financial literacy research. All five of these factors should interact and build towards “long-term financial security and the avoidance of suboptimal financial decision-making.” Financial education, then, can focus on any of these individual aspects, especially depending on the age of the student; second graders may find more use in multiplication than in a simulation of the stock market, for example.

With this vision of financial literacy in mind, Kasman, Heuberger, and Hammond surveyed standards in all fifty states. Indeed, forty states include substantial financial literacy requirements, but only three (Missouri, Tennessee, and Utah) require actual financial literacy classes for high school graduation. More often, the standards are integrated into the standards for another subjects, such as economics or social studies. The authors emphasize that requiring districts to implement these standards, regardless of their form, is more important than developing independently-listed guidelines.

Topics covered in the standards overlap quite a bit. Some of the most common are saving and investing, credit and debt, and investment strategies. Notable are states that connect finance and postsecondary education. Take Mississippi, which teaches students how to use W-4 and 1040EZ forms, or Utah, Texas, and Alabama, which all require lessons on how to complete the FAFSA. Twenty-seven states also have standards for basic financial education in grades before high school. These focus mainly on foundational skills, such as identifying short-term financial goals.

Brookings also examined the materials each state offers its educators to prepare them to teach financial literacy. Some states provide online curriculum, such as Florida’s Finance Your Future platform, which allows teachers to build custom, interactive finance lessons. Private organizations sometimes partner with states to offer weekend training seminars or their own curriculums. As the authors point out, the confidence teachers gain through professional development is critical to boosting student learning.

Studying the effects of financial literacy programs is challenging. Some studies have correlated robust financial education with higher savings rates and better credit scores later in life. But other research finds no effect on future behavior, and a handful of studies find that better math education is more strongly correlated with future financial success than is finance-specific coursework. Financial literacy education is hard to study on a wide scale because every state, even every district, approaches it so differently. The authors here call for more research, not just into financial well-being before and after the implementation of standards, but also into the effects of varying implementation efforts between districts in the same state.

The stakes of financial education are high. The average teenager earns $290 per month, and before long they’ll have to navigate the student-loan landscape. Fortunately, more states than we may realize are integrating financial literacy standards into their schools.

SOURCE: Matt Kasman, Benjamin Heuberger, and Ross A. Hammond, “A Review of Large-Scale Youth Financial Literacy Education Policy and Programs.” Brookings Institution (October 2018).

On this week's podcast, Halli Faulkner, national policy director at the American Federation for Children, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss her organization’s annual school choice guidebook. On the Research Minute, Adam Tyner examines whether better student supports in elementary school can reduce high school dropout rates.

Terrence J. Lee-St. John et al., “The Long-Term Impact of Systemic Student Support in Elementary School: Reducing High School Dropout,” AERA Open (October 2018).