Few people in education advocacy have had a greater impact than Kate Walsh. In her twenty-year career leading the National Council on Teacher Quality, no one has done more to make raising the level of teacher preparation a focus of reform efforts. The organization’s closely watched Teacher Prep Reviews earned her high-profile enemies among complacent ed school faculty and their apologists, but have driven demonstrable changes and improvements in how aspiring teachers are prepared for the classroom. Under her leadership, NCTQ became a go-to source of data on state laws and regulations that impact the teaching profession; pulled together databases of teacher contracts, school board policies, and salary schedules; and otherwise made a habit, as Walsh recently observed of “wrestling long-shielded data away from generally unwilling public institutions.”

Anyone who knows her also appreciates Walsh’s no-nonsense communication style and inability to be anything less than candid. Those qualities are on full display in this exchange—the first in what is intended to be an ongoing and occasional series of “exit interviews” with prominent educators, advocates, and policymakers who are leaving high profile positions, and are thus able to be particularly forthright about their work and the challenges faced by those who will take it up in their absence.

Why are you leaving?

I’m leaving mostly for personal reasons. My husband’s retired and we both want to travel before someone has to dab the spittle from our chins. But I also have to admit that I prefer to leave on a high note. As you age, you begin to encounter a certain amount of irrelevance in how other people in the work world respond to you. And if you’re at all sensitive to how you’re being received, you come to realize that you’re no longer speaking the same language as the rest of the people in the room. There is just something to aging where there is a subtle signal that says you’re not quite as relevant as you once were.

I sometimes think there should be term limits for people in this work. After a certain number of years, it’s time for either a fresh set of eyes or different approaches to the problems that we set out to solve.

Well, if you want me to be totally inflammatory about this, I think it’s more of a problem with men not knowing when to go than is the case for women! Men are much more likely to try to stay professionally active and on the scene. So I wanted to leave when I was still a credible voice and not yesterday’s news.

I’m already self-conscious about that. If you spend enough time in this work, you almost bore yourself saying the same things over and over again.

As we age, we certainly acquire an incredible amount of wisdom which is immensely valuable. The experience I have at my age allows me to intuit pretty quickly how to handle certain situations. It’s made my job very manageable the past few years, maybe even too easy at times, because I don’t have a whole lot of question marks in my mind about what I should do about some things, certainly more so than was the case with my forty-year-old self.

However, I will say that the racial politics of the last few years have tested me. The appropriate attention to DEI issues in the education arena has unfortunately come at the expense of other really important issues that continue to be no less relevant, but our sector seems incapable of accommodating more than one issue at a time. Frankly, I’m not all that comfortable with some of the rhetoric, mostly because it only seems to demand of us a lot of endless conversation that is rarely productive. I’m basically a doer, and have never been able to sit through any meeting without fidgeting, but I profess that some of the DEI conversations have been nothing short of frustrating. Conversely, my largely younger staff found my unwillingness to indulge them on this front equally frustrating! Instead of coming off as compassionate, I could come off as dismissive or indifferent, but it was never because I didn’t care about structural racism—I’ve fought my whole professional life against it. No, I bristled at the public gamesmanship, where we’re judged by our facility with certain words or phrases rather than our actions or accomplishments. In meetings, it felt like someone was keeping score and me being of a certain age made me suspect. One thing was clear, that everyone is living in fear of being called out. That’s not healthy, and I suspect it will ultimately backfire.

It feels like we talk now more about who the teacher is than what the teacher does when it comes to teacher quality.

The focus on how a teacher identifies, racially, ethnically, sexually, without any recognition that they need to know something to be an effective teacher has been really demoralizing for me. I have had to be extremely careful about sounding off on it too much because my voice is not the best voice to make this observation. The research is clear. Black kids benefit a lot from having Black teachers, but there is no research suggesting that Black teachers don’t also have to know something about their subject matter. We need people of color who are willing to publicly acknowledge this truth, that focusing solely on the identity of a teacher is a very narrow, even skewed, way to decide who’s qualified to teach. What I have say at this point is too easy to dismiss.

Let’s talk wins and losses. As you glance backwards over twenty years running NCTQ what are you proudest of? What’s left undone?

Our impact in teacher preparation is hands down our biggest win. I am confident that twenty, thirty years from now it will be the legacy of NCTQ—not to mention the smartest investment made a relatively small group of funders who believed in what we’re doing. We proved that it was possible to get teacher preparation programs to change what they teach—something almost no one believed was possible. We now have three concrete pieces of evidence that programs make changes as a result of being rated with measurable progress in the quality of preparation in teaching kids how to read, managing student behavior, and ensuring elementary teachers know enough math to teach it. That’s an amazing story and the one I’m most proud of.

In terms of losses, certainly the biggest loss is how close we came to seeing states and districts adopt better teacher evaluation only to have those wins squandered. We made the mistake of pushing radical changes in teacher evaluation at the same time that the country was contemplating what appeared to be a new curriculum (though it wasn’t that at all), the Common Core State Standards. The two sunk under their own weight. But I know that things come around in cycles and that at some point we’ll get another shot at it. Who knows when that will be, but it will happen because it’s right for teachers and kids.

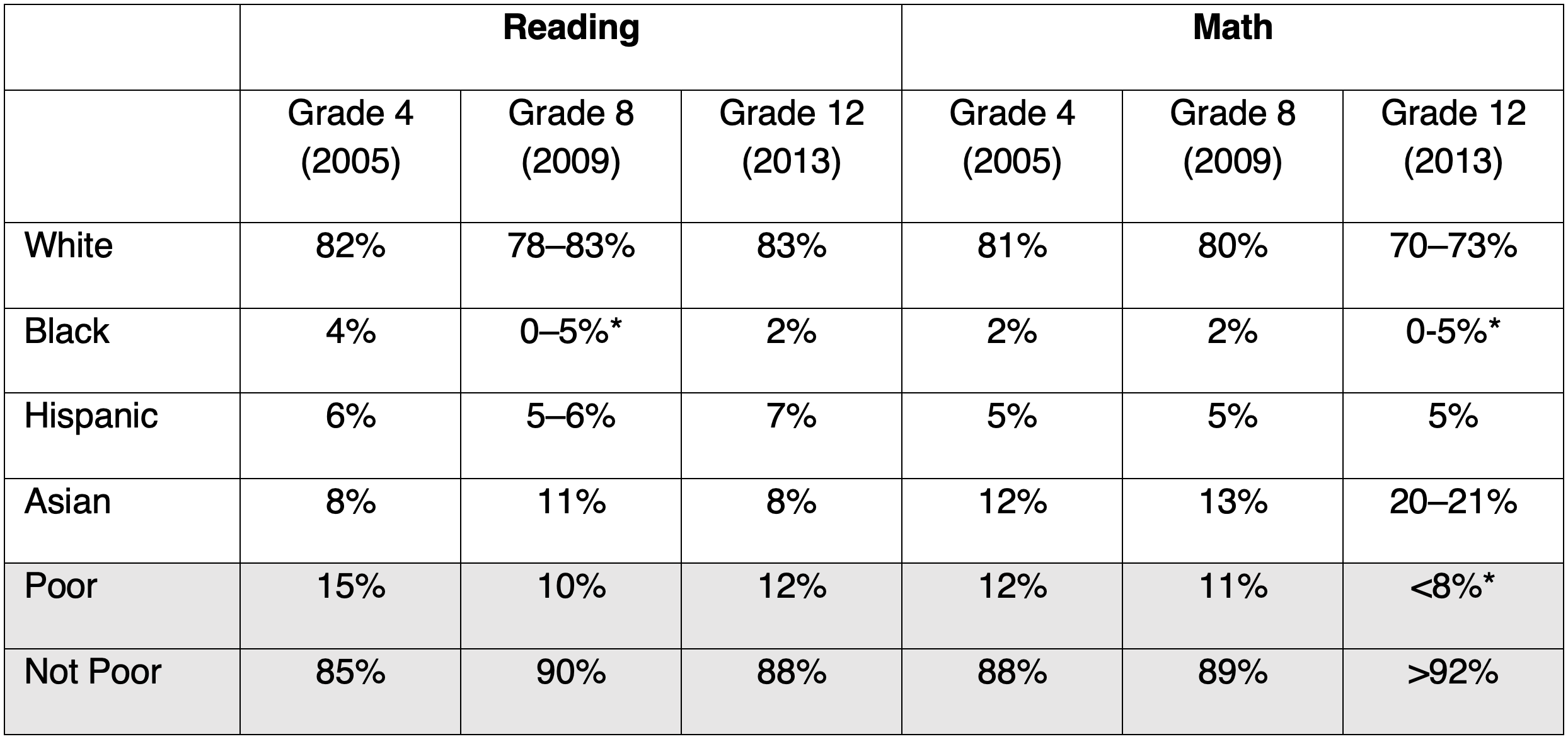

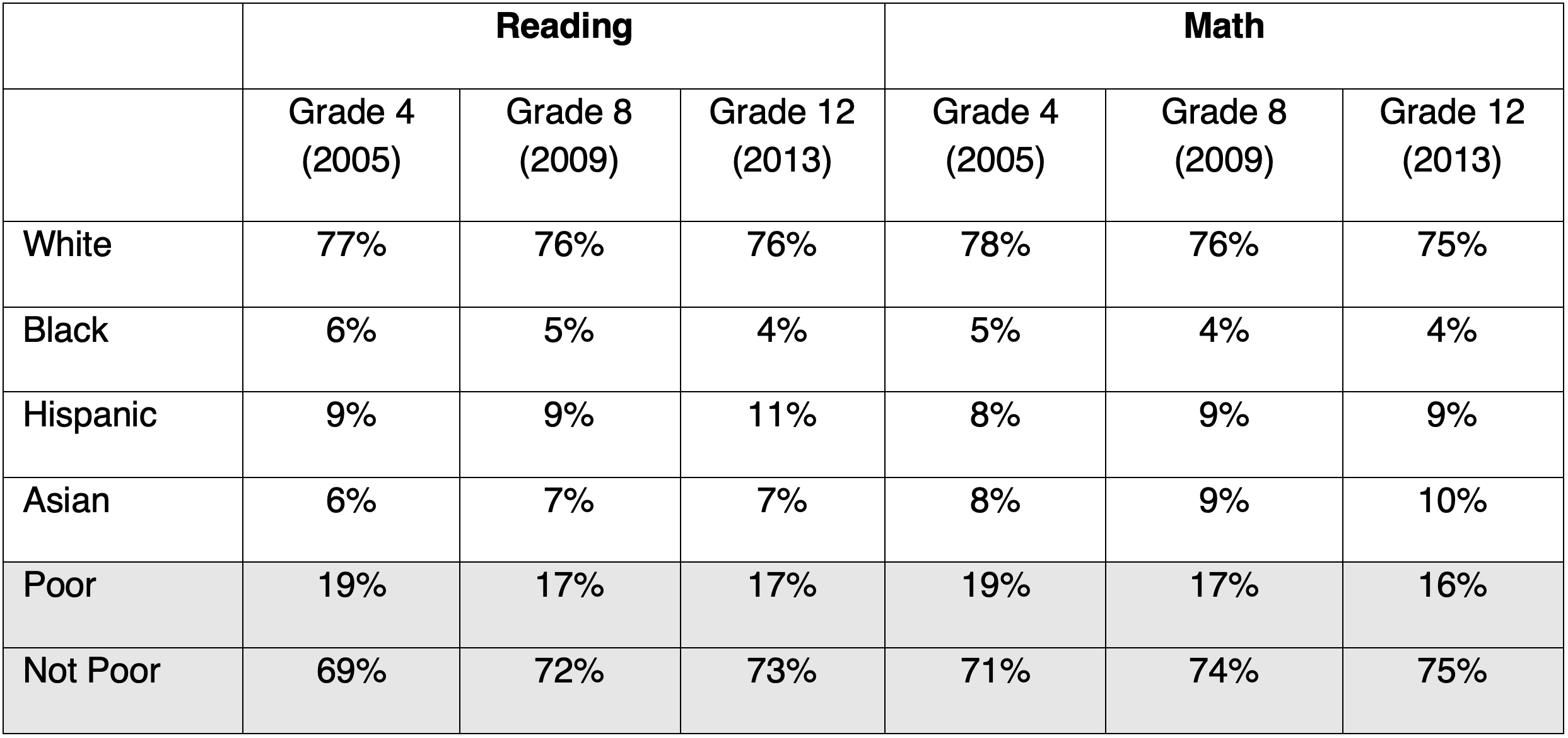

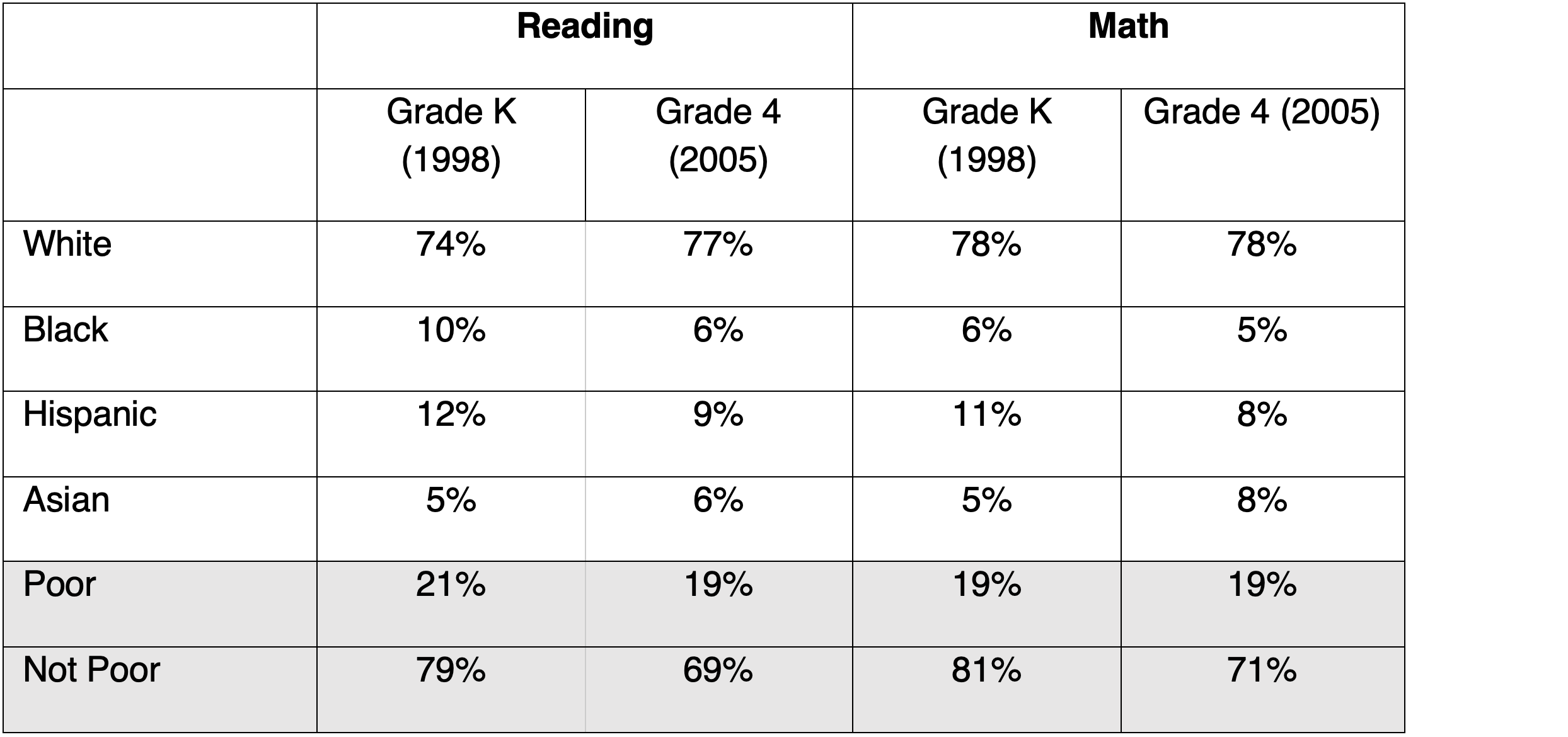

Let me add one more thing. I’m not sure I would classify this as a win or a loss, but I do look back on the last couple of decades and think that we as a nation wasted a unique opportunity to improve kids’ outcomes in reading and mathematics. When I think back on the millions, perhaps billions of dollars that were invested in K–12 education reform, I wish we had been louder advocates for investing in the fundamental need for kids to know how to read and become mathematically literate. We all allowed ourselves to get so distracted by other issues—like teacher evaluation! If we had only concentrated on ensuring that teachers were well prepared to teach reading and math and that schools only used high quality curricula—which is thankfully happening on the reading front at long last—we would be seeing a different educational landscape right now. Nothing matters more than reading and math. Show me a kid who can read and that’s a kid who will be happy and thriving in school and no doubt life. It’s that simple.

Your twenty years running NCTQ overlaps with the rise perhaps the fall of the ed reform movement. Any lessons learned? What are the takeaways?

I tend to be more personally introspective, marching to my own drummer, rather than thinking about where the ed reform movement went wrong, but in my opinion the movement largely died after 2015. At the time, I was shocked at the speed at which people who had identified with the education reform movement jumped ship, and it’s fair to include some of the foundations here. It was just astounding how quickly many walked away, leery of the controversy of the previous decade—as if it was ever going to be possible to get this work done and avoid controversy. Whereas I once would go to a PIE Network meeting (convening for state and national education advocacy groups) and everyone would be chasing the same goals, that’s no longer the case. The agendas are much more diffuse.

There’s a lot less talk about learning, that’s for certain. Our attention has also shifted from kids to adults. If we do focus on kids, it tends to be about their emotional well-being. I find that ironic because we know the one thing that really sparks joy in children is learning and the sense of accomplishment that they receive. I always credit [Education Trust founder] Kati Haycock with her relentless drumbeat that really got us focusing on what matters. Her response to everything was, “Is that what’s good for kids? What about the kids?” Kati inspired that moral outrage about the impact of adult decisions on kids. And that’s largely gone or, if not gone, misdirected.

I’ve said for years that no field has a poorer grasp of its own history than education. So it’s not entirely surprising to me that people forget, or that you have to fight the same fights over and over again.

I don’t know that I agree entirely. I look back on what motivated me when I got into education reform in late the early 1990s; I did a lot of work in Baltimore city schools. I think public education has made progress that hasn’t been entirely erased. I’m not going to paint an overly rosy picture here, but I think the attention to data and research has really been a gift to the field. It’s filtered its way down to the district level, if not the school level. The industry of educating kids is full of smarter people than it once was. Teach For America may not have solved student achievement issues, but they have definitely infused the profession with a lot of smart and creative thinkers. There’s considerably more talent out there than there once was.

If the ed reform movement died five years ago, what’s sustained you since?

While I’ve always enjoyed spending time with other reformers, I’ve not really depended on the movement to set NCTQ’s strategic direction program or really even to spark my own passions. If I had gone along with everyone else, I’d be clamoring to get rid of licensing tests now. Nor would I have spent the last few decades making so much noise about reading instruction. Until recently, NCTQ has been the only organization in the country really banging the drum on reading. Thank goodness that is now changing. States and districts are more serious about the science of reading than they’ve ever been. However, I will also note that many people who call themselves education reformers, competing with themselves for how many times they can say “equity” in a conversation, have been strangely silent on this issue, ironic in that it is the greatest civil rights issue of our times.

The “science of reading?” I don’t love the phrase, but it sticks so I use it.

You know that was my invention you’re insulting.

I’m not insulting it because it’s gained traction! Nothing else has.

It’s kind of silly story, but when we were writing about reading twenty years ago, everyone was referring to good reading instruction as “SBBR,” which stood for Scientifically-Based Reading Research—hardly a good way to engage the general public! <laughs> I just said, “We’re just going to have to call this by something else and came up with the “science of reading.” It stuck—for good or for bad.

What’s next for Kate Walsh?

I think I’d like to stay involved in the reading battles. While there are many dedicated researchers in that fight, there aren’t enough people with policy expertise in the mix. One thing I know I won’t do is write a book that no one reads. I did threaten for years to write a half snarky, half grateful book about philanthropy—I do have some stories!!—but I basically concluded that we should be mostly grateful for the incredible network of philanthropy in this country. No other country has such a thing, so I just needed to shut my mouth. Maybe that’s as good a way as any to close this conversation.