The Parable of the River: Bedtime reading for the education reform (A.K.A. "repair") community

Five reasons we all should care that a new NAEP is almost here

Wonkathon 2018: In light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere, do our graduation requirements need to change?

The effectiveness of Los Angeles's new teacher hiring and screening process

Five reasons we all should care that a new NAEP is almost here

Wonkathon 2018: In light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere, do our graduation requirements need to change?

Howard Fuller on school segregation

The effectiveness of Los Angeles's new teacher hiring and screening process

Online learning modules as an aid to science education

The Parable of the River: Bedtime reading for the education reform (A.K.A. "repair") community

Once upon a time, there was a small village on the edge of a river. The people there were good, and life in the village was good. One day a villager noticed a baby floating down the river. The villager quickly swam out to save the baby from drowning. The next day this same villager noticed two babies in the river. He called for help, and both babies were rescued from the swift waters. And the following day four babies were seen caught in the turbulent current. And then eight, then more, and then still more! The villagers organized themselves quickly, setting up watchtowers and training teams of swimmers who could resist the swift waters and rescue babies. Rescue squads were soon working twenty-four hours a day. And each day the number of helpless babies floating down the river increased. The villagers organized themselves efficiently. The rescue squads were now snatching many children each day. Though not all the babies, now very numerous, could be saved, the villagers felt they were doing well to save as many as they could each day. Indeed, the village priest blessed them in their good work. And life in the village continued on that basis.

—Christopher Cerf, former superintendent of public schools in Newark, New Jersey.

***

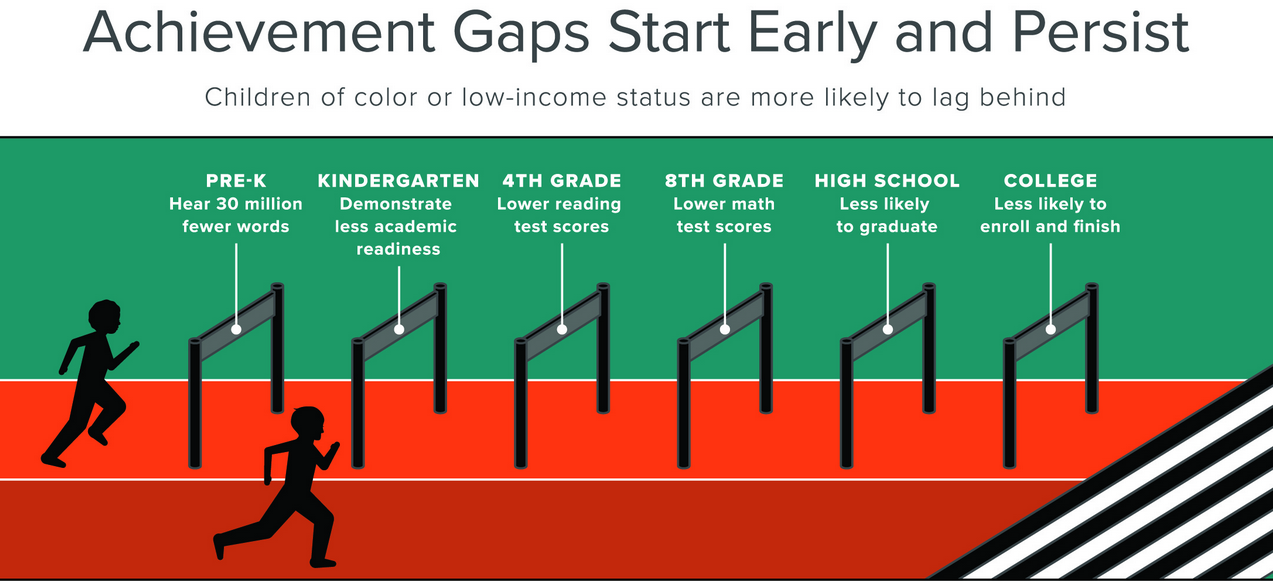

For those of us who work in the “small village” of K–12 schools, this river parable symbolizes the turbulent waters our youngest students must navigate every day. And it surfaces an uncomfortable truth—rarely confessed—that largely explains the grindingly slow progress of education reform and the withering fight against entrenched child poverty.

The overwhelmed “rescue squads” capture our valiant but tragically insufficient struggle to effectively educate the more than four million children who annually enroll in kindergarten, far too many of whom enter school a year or more behind their classmates in academic and social-emotional skills.

On November 14, in his keynote address at the inaugural School Readiness Forum, Chris Cerf shared this allegory to describe the ongoing challenge faced by K–12 educators. After his speech, I had the honor of moderating a panel he was on, along with Shael Polakow-Suransky, the president of Bank Street College of Education; Barbara Reisman, a senior advisor of the Maher Charitable Foundation; and Sarah Walzer, the CEO of the Parent-Child Home Program.

“Many have heard about the 30-million-word gap—the difference in the number of words heard by low-income children and those heard by well-off children before they even enter kindergarten. That gap is devastating, but in too many cases it is only the beginning of a gap that begins in the birth-to-four-years period and continues to grow as children enter school and move through classrooms unprepared to be there,” said Sarah Walzer on the panel.

Indeed, a consensus is growing among educators that the deficits a child experiences during ages zero to three are inextricably linked to almost inevitable adverse, long-term harm to their well-being later in adulthood. Even non-academic institutions like the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneaopolis have generated evidence-based infographics like the one below to depict the reliably predictable and negative lifelong effects of trauma before the age of five.

SOURCE: The Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis

As Shael Polakow-Suransky argued in an op-ed for the New York Daily News, “Missing this small but vital window of opportunity leads to intense efforts later in our schools to try and support students who are struggling. Most of the achievement gap between rich and poor children is already evident by kindergarten, and it stubbornly persists as students enter and complete middle and high school.”

For leaders in K–12 public education, this recurring theme of helplessness to reverse adverse early childhood experiences is an achingly bitter pill to swallow. No one wants to believe that our efforts are futile. Yet despite decades of extraordinary efforts by incredibly talented and committed K–12 educators, and more than $600 billion spent annually, the sobering reality in most places seems to be that, absent a transformation in how children are nurtured in utero and in the cradle, “the inequality that begins before kindergarten lasts a lifetime,” as Heather Long said in the Washington Post.

But we must fight to ensure that early hardships do not necessarily have to determine destiny. Though the river parable sadly analogizes the perpetual and often unwinnable game of academic catch-up for under-resourced children who enter kindergarten far behind, the story’s final passage commands us to seek out the root causes of the crisis of too many “floating babies”:

One day the villagers noticed a young man running northward along the bank. They shouted, “Where are you going? We need you to help with the rescue.” He responded, “I am going upstream to find the son of a gun who is throwing these kids into the river!”

***

The promising focus of the aforementioned School Readiness Forum was to explore new ideas and practical ways to “head upstream” to prevent the K–12 achievement gap.

As an example, the non-profit charter management organization I lead, Public Prep, announced a first-of-its-kind partnership with the Parent-Child Home Program that Sarah Walzer leads. Through the partnership, younger siblings of current students at our four Boys Prep and Girls Prep Bronx campuses will receive almost one hundred thirty-minute home visits before they receive automatic lottery preference into PrePrep, our universal preschool program that begins with four-year-olds.

For two years—two times each week—a trained, community-based early-learning specialist will bring the family a new high-quality book or educational toy as a gift. Using the book or toy, the specialist will work with the child and the child’s caregiver in their native language to model reading and conversation and do activities designed to stimulate parent-child interaction and promote the development of the verbal, cognitive, and social-emotional skills that are critical for children’s school readiness and long-term success.

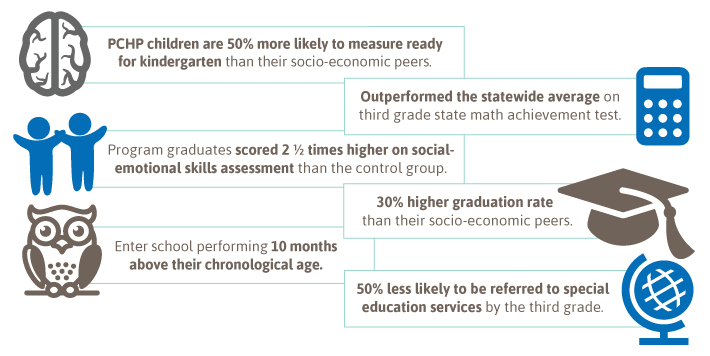

For more than fifty years, Parent-Child Home Program has demonstrated that its research-based home visiting model has consistently and profoundly improved children’s academic performance, as this infographic demonstrates:

SOURCE: Parent-Child Home Program

This home-visiting partnership epitomizes Public Prep’s philosophy that educators have to start helping students early in their lives, and do so with the end in mind. It has the potential to be a game-changer. By beginning interventions as young as eighteen-months-old, it can significantly alter students’ trajectories.

Yet despite this promise, the likelihood of home visiting becoming a systemic solution is dampened by the fact that the United States currently spends just one-twentieth of its annual K–12 budget on early-childhood education and care.

This ought to change, especially considering recent scientific studies that suggest we must urgently reverse the effects of adverse childhood experiences. Conducted in the emerging field of human neuroscience, one study found that the brain is not structurally complete at birth, and that a baby’s pre-natal and early familial engagement can either strengthen or weaken brain architecture, which provides the foundation for future learning, behavior, and health. And the Centers for Disease Control, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Harvard University Center on the Developing Child all report that toxic stress within the first three years of life is an identified risk factor that significantly elevates the odds that a child will have one or more delays in their cognitive, language, or emotional development.

This new research expands the knowledge base that trauma created or exacerbated by being raised in a fragile family, intertwined with child poverty, dramatically increases the probability that a child will suffer consequences well into adulthood.

It is why leaders in K–12 education reform must deploy a two-generation bookend approach. First, seek out supports for our youngest scholars before they enter kindergarten to increase the chances of healthy infant brain development. Second, throughout students' K–12 education, when volatile periods often compromise the development of their adolescent brains, proactively intervene to emphasize self-regulation and impulse control. We must exercise our intellectual, moral, and practical responsibility to empower teenagers to break the cycle by helping them develop attitudes and behaviors more likely to prevent the creation of fragile families in the first place.

Young people are coming of age at a time when our nation is in the midst of a five-decade explosion in the rate of multiple, non-marital births—across all race and all states, especially to women and men at or under the age of twenty-four—that is seismically shifting family structures in a way that puts children at risk.

Despite these cultural norms, beginning optimally with students entering eighth grade, we must help the next generation develop a framework for making life choices as they embark upon the next twelve years of their lives in high school, college, and young adulthood—during which they’ll make myriad critical decisions that will have lifelong consequences, positive or negative.

***

In Chris Cerf’s aforementioned speech, he shared that, after thirty years of working as a history teacher, deputy chancellor, district superintendent, and state commissioner, he had come to a conclusion: Rather than call the work to improve K–12 outcomes “education reform,” a more appropriate title would be “education repair,” given the armada of “rescue squads” our “village” has had to deploy to remediate very young children.

But we don’t have to be in the business of repair. In a different era, Frederick Douglass once noted, “It is easier to build strong children than to repair broken men.”

On the front end, we know that effective early interventions like home visiting can improve school readiness and reduce chronic exposure to toxic stress that inhibits brain development. And on the back end we can help teenagers entering adulthood reframe how they think about the timing of their own family formation to give themselves—and their future children—the best chance of success.

See you upstream.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

Five reasons we all should care that a new NAEP is almost here

It’s become fashionable in ed-policy circles to decry “misNAEPery,” coined by Mathematica’s Steven Glazerman and defined as the inappropriate use of data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress. It’s an important caution to us pundits and journalists not to make definitive declarations about what might be causing national or state test scores to rise or fall when we really have no idea of the true cause or causes.

But like all good things, the crusade against misNAEPery can be taken to extremes. It’s hard to use NAEP results to establish causation (more on that below), but NAEP scores and trends have great value and reveal much that’s important to know, and therefore the influence they wield is generally justified. In short, just because NAEP scores can be misused doesn’t mean they are useless.

As we look ahead to April’s release of the 2017 NAEP reading and math results for states and the nation, here are five reasons why policymakers, analysists, and educators should pay close attention:

- Tests like NAEP measure skills that are important in their own right. To quote President George W. Bush, “Is our children learning?” is still an essential question for our education system. What gross domestic product is to economics and employment rates are to labor policy, student achievement is to education. A fundamental mission of our schools is to teach young people to read, write, and compute; the whole country deserves to know how we’re doing. And while building these basic skills is not the only job of our K–12 system—or even of our elementary and middle schools, whose students’ performance is what we’ll see in forthcoming fourth grade and eighth grade results—they are surely at the center of the enterprise.

- Test scores are also related to long term student success. Test scores are not “just” test scores. They’re related to all manner of real-world outcomes that truly matter. Eric Hanushek and others have shown that countries that boost pupil achievement see stronger economic growth over time. Raj Chetty et al. have found that increased learning, as measured by tests, predicts earnings gains for students a decade later. When we see test scores rise significantly, as we did in the late 1990s and early 2000s, we are watching opportunities open up for young people nationwide. And when scores flatten or fall, it’s a warning that trouble lies ahead.

- NAEP is our most reliable measure of national progress in education or the lack thereof. Because NAEP is well-designed, well-respected, and zero-stakes for anybody, it is less susceptible to corruption than most other measures in education. Unlike high school graduation rates, NAEP’s standards can’t be manipulated. Unlike state tests, the assessments can’t be prepped for or gamed. Yes, a few states have been caught playing with exclusion rates for students with disabilities (we’re looking at you, Maryland), but by and large NAEP data can be trusted. In this day and age, that’s saying something. And while international tests like PISA and TIMSS give us critical insights about our national performance, NAEP is the only instrument that provides comparable state-by-state outcomes. Speaking of which…

- NAEP serves as an important check on state assessment results, helping to expose and perhaps deter the “honesty gap.” Way back in 2001, Congress mandated that every state participate in NAEP (in grades four and eight in reading and math) as an incentive for them to define “proficiency” on their own tests at appropriately challenging levels. Well that clearly didn’t work, as our Proficiency Illusion study showed in 2007, but eventually it put pressure on states to develop common standards and more rigorous assessments. The “honesty gap” between the lofty level of academic performance required for students to succeed in the real world and what state tests say is good enough has closed dramatically in recent years. But there’s an ever-present threat that it could open up again. NAEP’s audit function is essential.

- In the right hands, NAEP can be used to examine the impact of state policies on student achievement, helping us understand what works. It’s not true that NAEP can never be used to establish causal claims; it’s just that it’s hard. Well respected studies from the likes of Thomas Dee and Brian Jacob, for example, have shown the effects of NCLB-style accountability on student outcomes using NAEP data. Reporters should be skeptical of most of the claims, boasts, and lamentations that they will likely encounter on release day, but that doesn’t mean they should discount methodologically-rigorous studies by reputable scholars. And NAEP can also be leveraged to allow for cross-state comparisons using state testing data, as we see in recent studies from Sean Reardon and others.

MisNAEPery is a crime. So is NoNAEPery. Bring on the results!

Wonkathon 2018: In light of diploma scandals in D.C., Maryland, and elsewhere, do our graduation requirements need to change?

VOTE NOW FOR 2018'S WISEST WONK! All twenty-three entries are now posted below, so as in years past, we’re asking the public who they think is 2018’s “Wisest Wonk.” The polls are now open, and voting will be done in two ways: with an online survey and on Twitter via "favorites." A voter can make their selection using one medium or the other, and can only cast one vote. Everyone will have until the close of business on Tuesday, March 20, to pick a favorite. We'll then tally everything up and announce our first-, second-, and third-place winners.

A recent investigation revealed that several high schools in Washington, D.C., skirted district rules to graduate large numbers of their students who didn’t meet the standards for earning diplomas. As Erica Green of the New York Times and others have argued, this type of malfeasance isn’t limited to the nation’s capital. It happened in neighboring Prince George’s County, Maryland, and there are reasons to believe it’s happening in plenty of other places.

It’s not hard to understand why. For a decade now, federal policy has required states to measure graduation rates uniformly, to set ambitious goals for raising those rates, and to hold high schools accountable for meeting such goals. But the same local administrators who have been charged with getting more students across the graduation stage also have considerable leeway—via course grades, credit recovery programs, and shadier practices—in determining whether students have earned the privilege.

Given how many children enter American high schools far below grade level, and noting how many states have been dropping external checks such as exit and end-of-course exams, the temptation for educators to ignore graduation norms is pervasive.

That’s no reason to excuse cheating, but it does point to a large systemic problem and a bona fide policy dilemma. It may imply that we’ve set unrealistic expectations about the number of students who can feasibly reach rigorous graduation standards. Or it may mean that we’ve been wrong about what kinds of standards make the most sense in twenty-first-century America—and whether they should be uniform for all schools and kids.

This year’s Wonkathon will tackle these issues head-on. We are asking contributors to address the following question: What standards should students meet to graduate from high school?

Some related questions contributors might consider include:

- Should students be required to complete a certain number of Carnegie units in specified courses? Pass a certain number of end-of-course exams?

- Do we need more than one type of diploma? Should states have an “honors” diploma indicating college readiness and a standard diploma indicating mastery of high school level material? Should students engaging in career and technical education be required to meet the same academic standards as “college prep” students, or can they be different?

- What systems or structures should be implemented to avoid the kind of cheating seen at D.C’s Ballou High School and elsewhere? If Carnegie Units remain part of diploma requirements, for example, how can we be sure that they’re earned, that grades are not inflated, and that credit recovery is not a scam?

- How should graduation rate targets be set so that goals are challenging but attainable? Is there a way to take into consideration the achievement levels of those entering a high school?

- Do we need a more fundamental reimagining of the American high school and the type of education and training our teenagers engage in?

What’s a Wonkathon?

For several years now, we at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute have hosted an annual “Wonkathon” on our Flypaper blog to generate substantive conversation around key issues in education reform. Last year’s, on how President Trump should structure his (still unborn) $20 billion school choice proposal, engaged twelve participants and can be found here.

As in years past, we’ll encourage our audience to vote for the “wisest wonk,” an honor previously conferred on such luminaries as Christy Wolfe, Seth Rau, Joe Siedlecki, McKenzie Snow, Claire Voorhees, Adam Peshek, and Patricia Levesque.

If you’re keen to jump in—and we hope you are—please let us know and indicate when we can expect your draft. We will publish submissions on a rolling basis, so please send yours as soon as possible, but no later than March 9. Aim for 800 to 1200 words. Please be sure to answer the fundamental question: What standards should students meet to graduate from high school? And send your essay to Brandon Wright, Fordham’s Editorial Director, at [email protected], as soon as it’s ready.

Let Brandon know if you have any questions. Otherwise, let the wisest wonk win!

***

This is list of all current published submissions, which we will post on a rolling basis until the Wonkathon is complete. Click on a proposal's title to read it:

- "Tie high school graduation to student attendance and passing grades" by Peter Cunningham

- "Let's make sure graduates actually know what's in the state standards" by Elliot Regenstein

- "To fix the gaming of graduation requirements, we need to overhaul high schools and our policies governing them" by Michael J. Petrilli

- "Look beyond four-year graduation rates" by Peter Greene

- "Make high school about content mastery, not time served" by Patrick Riccards

- "Award a variety of high school diplomas with different requirements, but honor them all the same" by Jeremy Noonan

- "Make diplomas meaningful through differentiation" by Lane Wright

- "Make high school relevant again" by John Legg and Travis Pillow

- "Graduation rates are not the real scandal. High school diplomas and how they are earned are." by Quentin Suffren

- "In reconsidering the high school diploma, don't overlook dropouts" by Alex Medler

- "Reformer, heal thyself. You've ruined high school." Max Eden

- "High school reimagined (and we truly mean reimagined)" by Jessica Shopoff, M.Ed., and Chase Eskelsen, M.Ed.

- "The special-education graduation conundrum" by Sivan Tuchman and Robin Lake

- "Let's expect more from our high schools" by Laura Jimenez and Scott Sargrad

- "Meaningful diplomas need external validation" by Sam Duell

- "How we should write high school requirements" by Ed Jones

- "Ask students what they want to do after high school" by Daniel Weisberg

- "Award three high school diplomas: 'basic,' 'career-ready,' and 'university-ready'" by Joanne Jacobs

- "Graduation rates are important—but also have issues as performance indicators. States can use ESSA's flexibility to address that." by Amy Valentine

- "Four guiding principles for fixing high school" by Eric Lerum

- "High school counseling and individualized plans are key to student success" by Nancy C. Herrera

- "Ensuring the quality and consistency of courses is fundamental to fixing high school" by Laura Slover

- "Fill in the missing building blocks of college and career readiness" by David Wakelyn

Howard Fuller on school segregation

On this week's podcast, Howard Fuller, renowned civil rights activist and education reformer, joins Mike Petrilli and Alyssa Schwenk to discuss school segregation. During the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines ways to help bachelor’s degrees better facilitate professional success.

Amber’s Research Minute

Mark Schneider and Matthew Sigelman, “Saving the Liberal Arts: Making the Bachelor’s Degree a Better Path to Labor Market Success,” American Enterprise Institute (February 2018).

The effectiveness of Los Angeles's new teacher hiring and screening process

We know that it’s hard to fire poorly performing teachers, especially after they earn tenure, so the more that districts can do to predict effectiveness ahead of time, the better.

This study by CALDER researchers Paul Bruno and Katharine Strunk examines whether a new teacher hiring and screening process in Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD), the second biggest district in the country, is actually ushering in more effective teachers.

Instituted in 2014–15, the Multiple Measures Teacher Selection Process is a standardized system of hiring with eight components whereby eligible candidates (those completing the application packet and meeting certification requirements) are scored on multiple rubrics. The eight components are a structured interview; professional references; sample lesson; writing sample; undergraduate grade point average; subject matter licensure scores; background (such as prior teaching or leadership experience); and preparation (such as attendance at a highly ranked college, evidence of prior teaching effectiveness or major in a credential subject field). The study uses a wealth of applicant data from 2014–15 through 2016–17, as well as teacher- and student-level administrative data for teachers who are ultimately hired and for their students.

Bruno and Strunk observe those individuals who pass the selection process, which typically means scoring a minimum of 80 percent, are considered eligible for hiring (totaling about 5,500 applications). The eligibility pool also includes about 10 percent of applicants who were granted an exception to the minimal passing requirement—both because principals can request that failing candidates be added back, and because failing applications are given a blind review by human resources staff and some are subsequently added back into the pool. Relative to the methodology, the analysts concede that the screening scores may serve as proxies for characteristics that administrators are actually observing in the interviews. Yet that’s not entirely bad if the process is also illuminating principals’ revealed hiring preferences through the interview rubric. Further, they conduct a number of statistical tests primarily intended to measure sorting bias—for example, new hires may accept easier placements—but find it is a minimal threat.

Results show that applicants who perform even better on the selection process (higher than 80 percent) are more likely to be subsequently employed as teachers, even though principals do not know their exact screening score. In addition, overall performance significantly predicts teacher outcomes once hired, including attendance, contributions to student achievement, and ratings on final performance evaluations. Specifically, a one standard deviation (SD) increase in overall score is associated both with teacher level value-added that is 16 percent of a SD higher in ELA and with as much as 73 percent lower odds of an unsatisfactory rating among all elementary teachers. Yet overall performance is not predictive of teacher retention. Moreover, the individual components of the selection process are differentially predictive of different teacher outcomes. For example, applicants are more likely to be hired if they have higher interview scores, sample lessons scores, or writing scores (among others) but undergraduate GPA and subject matter scores are not predictive. Finally, those who fail to meet the minimal score and are granted exemptions are less likely to be employed by LAUSD, despite the fact that they were actively chosen by one or more individuals for the exemption.

Clearly there’s a lot here to chew on but inquiring minds of district officials want to know: Can we hone these somewhat comprehensive hiring protocols to pinpoint what is most important in predicting effectiveness? Yet the study finds that when you tinker too much in an attempt to predict one particular outcome (like value-added, for instance), it greatly reduces the ability to predict other important outcomes such as attendance and retention. In other words, if you try to go too narrow on the selection process, it may come back to haunt you. Because, after all, forecasting teacher greatness ain’t easy.

SOURCE: Paul Bruno and Katharine O. Strunk, “Making the Cut: The Effectiveness of Teacher Screening and Hiring in the Los Angeles Unified School District,” CALDER (January 2018).

Online learning modules as an aid to science education

If a renewed focus on curriculum as a driver of improvements in K–12 education is in the cards, then a recent study from University of Oregon and Georgia Southern University scientists is good news indeed. It shows that four well-designed online science modules increased student achievement across all student subgroups, and especially for English as a second language (ESL) students and students with disabilities.

The study, a randomized controlled trial with over 2,300 middle school students and their teachers in thirteen schools in Oregon and Georgia, was conducted over three school years between 2014 and 2017. Each year, students in the treatment group completed one module—described as “enhanced online textbooks.” The modules covered life science, Earth and space science, and physical science; were aligned with Next Generation Science Standards; and included teacher professional development regarding their effective use prior to the start of each school year. Pacing was left up to the teachers, although the minimum duration reported was ten weeks. Control group teachers taught these topics “as usual”—i.e., in class without online content. Students in both groups completed pre-tests and post-tests around the specific content of each module.

The researchers found that students in both groups improved their science knowledge overall, but the treatment group’s gains were nearly three times as large as those of the control group. And growth experienced by ESL students and students with disabilities in the treatment group was almost as large as the average treatment group pupil. Moreover, student and teacher satisfaction surveys showed generally positive responses to the modules.

So what’s the secret sauce in these online modules? Everything and the kitchen sink, it seems: project-based learning; collaborative work; interactive multimedia elements (read: games); multiple supports for ESL students, including videos with subtitles and spoken word versions of text; and all of it broken down into bite-sized chunks in accordance with the cognitive-affective theory of learning with media. The multiple formats are intended to help students draw on culturally relevant background knowledge and generate discussion; allow for the construction and acquisition of knowledge such as science-specific vocabulary; provide corrective and explanatory feedback on quizzes and other assessments; and allow students to practice, hypothesize, and experiment in order to develop scientific thinking skills. All this and more!

To be clear, the researchers are not claiming to have found a curricular silver bullet. The overall achievement level of all students was not spectacular—the highest post-test scorers averaged just 66.1 percent correct—and the growth observed is limited to these modules and their content only. It’s unclear, for example, whether the same model would work with chemistry. But the sustained, across-the-board growth rates produced by these modules are a strong start toward those goals. The remarkable results for ESL students and students with disabilities must also be taken seriously. These online modules should be strong contenders for integration into science courses across the country, especially in areas where strong science teachers are hard to come by. More data about how they can best be incorporated into course sequences and how to leverage them to boost achievement toward mastery seems imperative, but we already know it’s promising.

SOURCE: Fatima E. Terrazas-Arellanes, et al, “Impact of interactive online units on science among students with learning disabilities and English learners,” International Journal of Science Education (February 2018).