How schools of choice respond to emails about prospective students who may be harder to educate

Dear districts: These are the glory days. Are you ready for tomorrow’s financial pain?

Education freedom (not) in the Free State

How schools of choice respond to emails about prospective students who may be harder to educate

The problem with "finding the main idea"

The Education Gadfly Show: Teacher strikes, Democrats, and ed reform

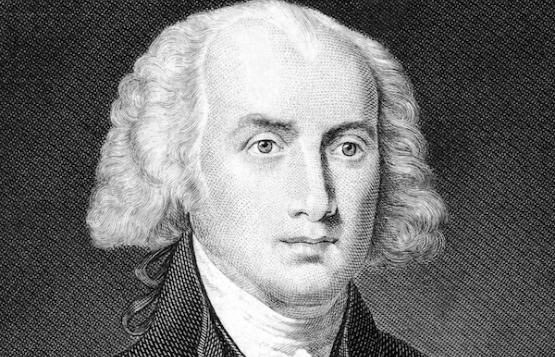

Knowledge is power: Why our students need less of Franklin's wit and more of Madison's wisdom

Jamestown, Valley Forge, the pioneers’ Conestoga wagons, and so much more—the skills of survival are woven into the American narrative. Our heroes include Thomas Edison and Steve Jobs, and today’s national conversation about education focuses on giving students the technical and career-ready competencies that ensure rewarding and fulfilling employment. Our renewed interest in “practical” learning recalls Benjamin Franklin’s sardonic take-down of the academic kind: “He was so learned that he could name a horse in nine languages; so ignorant that he bought a cow to ride on.”

Focusing on skills makes a virtue, too, of America’s heterogeneity. In the England of my own youth, curricula and assessments in the language arts were one and the same: Examiners assigned the texts, teachers taught them, and the exams required students to write about them. That meant teachers never faced such questions as why those texts, those authors, and not these (insert one’s own cultural favorites)? In today’s United States, by contrast, focusing on leaning to master reading skills makes content a secondary concern, one left to choices by teachers, districts, or states. This has a certain, if questionable, logic: Students in Mississippi can be taught about the “War of Northern Aggression” and read As I Lay Dying, while their peers in Massachusetts study the Civil War and The Scarlet Letter. Yet this variability, even agnosticism, regarding the selection of content and texts gives rise to a deep problem: In too many U.S. schools, students spend little time with Faulkner or Hawthorne or carefully reading other whole books. Why should they, when what unifies our educational system is that students across the land will be assessed on their prowess at “finding the main idea” across bits of texts pulled from readings they haven’t read except by chance, of uncovering inferences in the fragments, and of learning random vocabulary words? The assessment-tail wags the curriculum-dog, pressing teachers to drill on those “reading skills,” especially when instructing students who are already behind.

More recently, our enduring focus on skills over content knowledge has received a double boost. Given the explosion of technology and access to information, it feels right to suppose that today’s students need “to learn how to learn,” to “think critically,” rather than mastering specific domains of knowledge. Second, we are told that social and emotional learning (SEL) is as important—some would argue more important—than academics and the results of academic assessments.

A few voices, such as E.D. Hirsch and Daniel T. Willingham, have long cautioned that this is national folly. Even as students are learning to read, which necessarily involves skills such as decoding, their greatest need is to build content knowledge. America’s reading gaps are not caused by skills shortages but by knowledge vacuums. When we provide even very weak readers with a story about a topic they know, finding the main idea is a snap. By contrast, give strong readers a passage about something they know nothing about, and they can stare at it forever with little chance of finding that same idea. As Hirsch recounts in Why Knowledge Matters, detailed data from France show that when that country abandoned its national, content-rich reading curriculum, the performance of all students declined, and the poorer the student, the more precipitous the loss. In the U.S., while we’ve seen reading scores rise in the early grades, NAEP twelfth-grade reading performance remains essentially unchanged from the early 1990s, and the tragically wide racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps show no signs of closing.

As for critical thinking: Try thinking critically about nothing in particular, for thirty seconds. Then, think critically about well-compensated jobs—brain surgeons, airline pilots, petroleum engineers. As you do so, notice the higher-order thinking that’s required of these professionals, but note, too, that it’s entirely based on thousands of hours of accumulated content knowledge. As for SEL, ample evidence suggests two-way correlations: Strong academics and strong SEL reinforce one another, and both correlate to long-term life prospects. Relegating academic content will prove as myopic as trumpeting self-esteem absent real achievement.

Today, we know that most teachers create their class materials by plucking them just-in-time from sites such as Pinterest, Google, and Teachers Pay Teachers. Then they mix their harvest—with little or no support—with fragments of district-provided materials. As a nation, we can do so much better by our children. Following on the strong example of Louisiana, the Council of Chief State School Officers is working with eight states as they plan policies to support the widespread use of high-quality instructional materials. ELA curricula such as EL Education, Louisiana's ELA Guidebooks, Wit and Wisdom, and Core Knowledge Language Arts offer open-education resources and content-rich material aimed at building background knowledge.[1] Creating outstanding curricula and preparing teachers to use it well needs to become the norm across the country.

At the same time, we should build assessments that enable students to answer questions using specific content. For years, the Latin Advanced Placement exam announced the texts it would examine in advance (perhaps they figured that Latin was just so esoteric that no one would notice). More recently, the AP American Literature exam added an essay question that requires students to answer using concrete knowledge of the books they have studied. It is exactly wrong to conclude that such essay questions—which are also asked in the International Baccalaureate—are suited only for the strongest of students. It is our less privileged students who most need the background knowledge that deep and wide reading provides.

In an age when fewer Americans study foreign languages, there’s probably no point in wishing that children knew the word for “horse” in more than just their native tongue. Our students need less of Franklin’s wit and more of Madison’s wisdom. “Knowledge will forever govern ignorance,” he argued, “and a people who mean to be their own governors must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” America loves proxies in education—multiple intelligences, focus on the whole child, metacognition. In the end, however, what counts is what is actually taught in actual classrooms, and how effectively children learn it. There should be no separation between the two: Enabling teachers to bring compelling, demanding content to their students is the healthy heartbeat of a good education.

1 Disclosure: As NYS Education Commissioner, I pushed for the funding that made the first edition of the EL Education curriculum available for free on line, and I serve on the Core Knowledge advisory board.

Dear districts: These are the glory days. Are you ready for tomorrow’s financial pain?

Psst, districts! We’ve seen this script before.

Back in 2008, it’s a fair bet that most school systems didn’t know they were in a financial boom before the Great Recession unleashed the bust, filling subsequent years with program cuts, furloughs, school closures, and fights about seniority-based layoffs. Today, signs suggest we’re once again at a peak, with a likely financial stumble headed our way.

Just like the years leading up to 2008, the last few years have yielded stronger growth in funds for schooling. And just like in 2008, there are signs of trouble ahead. For districts, a fiscal downturn can trigger the equivalent of a debilitating migraine: Pain comes from every direction and little seems to quell it.

While we can’t predict how an economic downturn will affect every district, we can anticipate some big-picture trends, and in doing so potentially tweak the script.

State revenues will likely stumble: This will hurt districts in some states more than others

Where districts may have been benefitting from a higher growth rate in state revenues in the last two years, that trend is likely to wane as tax revenues slip in a downturn. Some states, like Wyoming, are considered more prepared, with stronger reserves and/or more stable revenues and expenses. But Moody’s designates seventeen states, including big-population states like Pennsylvania, Virginia, and New Jersey as “significantly unprepared” for even a moderate recession.

Changes in state funding formulas have made districts in twenty-one states more reliant on state funding (versus funding from local sources) than a decade ago, according to analysis of U.S. Census data. That means a dip in state revenues will impact a bigger share of local districts’ pie. (Local funding tends to hold steadier in recession.) And districts in some states, like Arkansas, Michigan, Kansas, and Wisconsin, are considered both unprepared for a downturn and more beholden to state revenues than in the last recession.

District obligations climb when the economy takes a hit

As counterintuitive as it seems, costs go up during an economic downturn. That’s because when the private sector curbs hiring, fewer teachers leave their districts to pursue jobs in the private sector. That means teacher shortages disappear, more people apply for teaching jobs, and districts can be more selective in hiring. These changes are desirable for learning, but costly for the district balance sheet. Typical teacher turnover rates involve teachers with some experience being replaced by newbies at the bottom of the salary scale. But when that turnover drops, the average teacher experience level increases—and with it, average salaries, even without raises. Pension obligations also grow, as more teachers shelter in place and accrue more seniority, triggering the next tier of pension benefits. Note, too, that a stock market drop means the pension fund isn’t yielding expected returns and may prompt calls for more public investment.

In education, labor feels like a fixed cost, and that makes it tough to cut spending

Labor typically makes up a district’s biggest expense. While most sectors don’t define labor as a fixed cost, any district trying to make cuts finds it’s nearly impossible to reduce staff, either politically or contractually. Announce a plan to cut librarians or the Latin teacher and it can trigger marches, online petitions, and sit-ins. It isn’t just because education is a public sector enterprise involving collective bargaining or the assumption that a teaching job is for life. It’s also that schooling is an incredibly human endeavor in which people matter a lot. Parents, students, and school staff form important relationships. Some staff play more roles than their title suggests: An amazing recess monitor may be what’s kept discipline rates low at one school, or a theater teacher may be what’s kept a generation of teens from dropping out. These school-level human factors don’t show up in a financial ledger and may foil a seemingly thoughtful plan to shrink staffing.

It doesn’t take much to destabilize a district

My Edunomics Lab colleagues and I analyzed spending of 140 mid-size and large districts with from 2000 to 2014. We concluded that districts don’t follow a common playbook when it comes to cutting costs. Budget changes resulting from relatively minor revenue adjustments took the form of a hiring freeze that affected staff types unevenly, and some shaving of non-labor expenses, like contracts and travel. But as little as a 0.75 percent drop in total revenue seemed to tip districts into more financial chaos. In these cases, the cuts were all over the map, with no consistency in which spending categories took the biggest hit. Some cut benefits or extracurriculars, others reduced support staff or raised core class sizes.

A deeper dive into media reports in some districts indicated that while budget-cutting districts would propose one set of reductions, what ultimately got cut was often something else entirely. The end result was often a reduction in expenses that garnered the least support, be it teacher aides, the theater program, or alternative school—possibly because the affected staff were less organized, the families impacted were less vocal, or the program didn’t have a loyalist on the board. The takeaway? The entire process can be reactionary. Political. And decidedly not strategic.

But districts have a chance to be strategic now while the good times still roll by preparing for the downturn. Below are some ideas that may help districts rewrite the script when revenues stumble.

Reduce recurring costs and resist more hiring

Districts can view current staff turnovers as an opportunity to stash more in reserves, use stipends to boost the pay for current staff to pick up some of the load, or issue a service contract. Reducing the overall staff count results in fewer dollars tied up in benefits and more dollars available to retain existing staff in a downturn.

But this requires districts to look beyond the current school year and see financial scarcity ahead. Evidence suggests that when they do, leaders make more cautious choices. After California districts were told they would need to boost their payments over the next few years to the state pension system, our research found districts reduced their hiring rate, amassed more in reserves, and invested more in contracts. After a gloomy forecast in Chicago, some principals worked to roll over funds to cushion their schools from future-year cuts.

Shift budget choices to schools, allowing them to protect what matters most

Many larger districts, from New York City and Baltimore to Houston and Atlanta, now deliver dollars, not staff counts, to schools via a weighted student formula and allow the principals to make tradeoffs that work for their buildings. If School A wants to keep its beloved Latin teacher, it might, for example, choose not to replace a vacant vice principal position. For this to work, districts must give schools flexibility to leverage their staff to best meet their students’ needs—and thoughtfully cut corners in ways that their communities can accept.

Cuts delivered by district fiat are likely to get more blowback than cuts made by a local school in collaboration with its community. Which brings us to the next section on trust.

Build trust around money, and engage community in tradeoffs

Money matters. But recent messaging research tells us words matter too. Districts can build trust with their staff and communities by explaining finances in terms of students, versus in terms of “deficits,” “efficiencies,” or “projections.” Trust is also higher when leaders share the numbers considered in tradeoffs: “Raising class size by one frees up $2,000 per teacher that we can use to raise pay,” for example. And it’s higher when the public is invited to participate in budgeting, such as through crowd-sourcing priorities for spending or cuts. Finally, because parents and teachers trust their principals more than their district, why not do more to engage principals in tradeoffs and encourage principals to communicate them? Hard-earned trust can help steady the system as it navigates a recessionary wave.

***

Let’s not pretend that any of these steps will remove all pain from a revenue crunch. But they could help insulate school systems from needless churn, better equipping them to make it through the inevitable downturn ahead without extinguishing public good will. That seems like a budget script rewrite worth considering.

Education freedom (not) in the Free State

I’ve lived in Maryland for more than four decades now and in recent years have been honored to serve on the state board of education and the statewide Commission on Innovation and Excellence in Education (a.k.a. Kirwan Commission). Certainly there are bright spots in this state’s K–12 system—some great schools, many fine teachers, forward-looking leaders, and more. What there’s not is much school choice—and that means that far too many children, most of them poor and minority, are trapped in district-assigned neighborhood schools that are far from bright spots. On Maryland’s new statewide report card, 180 public schools received just one or two stars (out of five possible); in Baltimore, those bottom-of-the-pack ratings applied to 60 percent of city schools.

It’s to be expected in any large education system that some schools will be duds. What’s not to be expected in the United States in 2019 is that families—unless they’re rich or very lucky—aren’t allowed to extricate their daughters and sons from such schools and move them to better ones.

Maryland has been this way for a long time. My own family first encountered it in 1985 when, upon returning from several years away, we petitioned our district superintendent to allow our son to attend a different school than the one nearest our home. Denied, said the bureaucratic reply, unless such a move would improve the school’s racial balance. So we put him in private school, grateful that we could afford to.

More than three decades later, the Old Line State continues to hold the line. It’s one of just a few states with no public-school choice law, meaning it’s totally up to individual districts whether to allow intra-district choice—and in none of the twenty-four districts, many of them sprawling for miles, is choice standard practice. Some are not too stingy about okaying individual transfer requests so long as these fit within the districts’ “out-of-area exceptions.” (Here is an example.) Nowhere does it suffice simply to say “My child needs a better school” or “School A has a curriculum that better meets my child’s educational needs.” As for transferring one’s child to a school in another district, surely you jest. (Or maybe you can pay tuition.)

One might suppose that charter schools would supply an escape route, but Maryland infamously—and for many years now—has the county’s weakest charter law. It’s entirely up to districts whether to allow any charter schools—just a few do—and those that exist have little true autonomy and inadequate resources. Charters are anathema to the powerful state teachers union, which wields immense influence in the legislature, where Democrats in both houses have long enjoyed a veto-proof super majority.

That political reality bodes ill for GOP governor Larry Hogan’s fresh and imaginative effort to strengthen the state’s charter sector. Past such initiatives have gone down in legislative flames in Annapolis and, sadly, there’s little reason to expect a different outcome this go-round.

The one small oasis in Maryland’s school choice desert is the two-year-old BOOST voucher program, which currently assists some 3,400 youngsters to attend 176 participating private schools. But as the EdChoice organization (formerly the Friedman Foundation) notes, that program “has several important shortcomings,” including its very low per-pupil funding level—averaging $2,300—and the fact that it’s subject to annual appropriations, meaning families cannot count on their children’s vouchers continuing from one year to the next.

The Kirwan Commission was charged with envisioning and proposing a radically improved K–12 system for Maryland, and it’s done a fine job of designing important changes in the traditional system. But when several of us sought to incorporate any elements of choice into its recommendations—even just explicit recognition of the legitimacy of charter schools—we were swiftly rebuffed. The closest our colleagues would come was to urge that a portion of the billions of additional dollars the Commission is recommending should follow students to the district schools that they actually attend. Even this modest move was resisted by district and union representatives, insistent that the central office knows best where the money should go and what it should be spent on. Not that “money following students” means much in a place where students and families have no right to change schools in the first place.

How schools of choice respond to emails about prospective students who may be harder to educate

It’s a common accusation leveraged against schools of choice, and especially charter schools: They “skim” students who they perceive to be easier to teach and avoid those they perceive harder to educate. In this clever new study, analysts Peter Bergman and Isaac McFarlin conduct an experiment to test whether that’s true. They send emails from fictitious parents (sneaky!) to nearly 6500 schools of choice—that includes traditional public schools in areas with intra-district school choice and charter schools—in twenty-nine states and Washington, D.C., asking if any student is eligible to enroll in the school and, if so, how to apply.

More specifically, the experiment randomly assigned an attribute to the child (or no attribute). The control or baseline email read, “I am searching for schools for my [daughter/son]. Can anyone apply to your school? If so, can you tell me how to apply?” Then they added a sentence to indicate one of four other treatment conditions: 1) a special needs requirement (“Her IEP says she has to be taught in a separate room”); 2) bad behavior (“She gets in trouble a lot for behaving badly in school”); 3) poor grades (“She’s been getting bad grades”); and 4) good grades (“She has good grades and good attendance”). They also randomly varied four other variables: students’ implied race through a “black-sounding” or “Hispanic-sounding” name, the household structure (implying a one- or two-parent household—i.e., “My husband and I are searching…”) and the gender of both the parent and the student.

They did two experiments; the first included charter schools only, and the second sampled from the largest forty districts in twenty-nine states and Washington, D.C., with intra-district choice and charter schools. The results from both were similar. For the latter, they matched charter schools to the nearest traditional school with the same entry grade and within the same district boundaries. They also use a variety of demographic, achievement, and census tract data from multiple sources as controls.

The key finding is that all schools of choice (traditional and charter) are less likely to reply to messages signaling that the potential applicant has bad grades, poor behavior, or an IEP, compared to the baseline message, which had a response rate of 53 percent overall. The email indicating poor behavior decreased the response rates the most, a reduction of 7 percentage points. The email signaling good grades and attendance had no discernible impact. In terms of the other randomized elements, only the message that indicated a Hispanic-sounding name resulted in significantly lower response rates at 2 percentage points.

When breaking out traditional public schools located in areas of choice versus charter schools, analysts find that both generally responded at similar rates, with one exception: Traditional schools are more likely to respond to the IEP message—by 5.8 percentage points—than are charter schools. And high value-added charters are less likely to respond (by 10 percentage points).

Analysts hypothesize that the higher cost of educating special needs students for a single charter school versus one affiliated with a school district (or local education agency, a.k.a. LEA) may make a difference, so they examine that too. But they find no difference in responses relative to whether the charter is its own LEA or associated with an LEA. However, they do find that charter schools in states that reimburse schools or districts for a portion of their realized costs of serving these students are 7 percentage points more likely to respond to the IEP treatment message than charter schools in other states. This suggests that funding or lack thereof is a key barrier for charters in serving children with special needs. Analysts also posit that their particular IEP message, which signaled a student who required a restrictive environment (“Her IEP says she has to be taught in a separate room”) could be particularly costly and therefore may have impacted the results.

To summarize, both charter and traditional schools of choice are equally likely to balk when presented with the opportunity to enroll students who are lower performing or costlier to educate. In other words, it’s not at all clear which is the pot and which is the kettle.

An open enrollment policy is the right and noble way to go. But we also can’t ignore the reality that students come into school with any number of needs, interests, and challenges. Instead of pretending otherwise, let’s not only support schools in embracing all children, but commend those that excel in educating kids who don’t fit the mold—and incentivize more of them to open.

SOURCE: Peter Bergman and Isaac McFarlin, Jr., “Education for All? A Nationwide Audit Study of Schools of Choice,” National Bureau of Economic Research (December 2018).

The problem with "finding the main idea"

OK, readers. It’s time for today’s “skills and strategies” lesson in reading comprehension. Today’s aim and standard is “finding the main idea of a complex text.” Please follow along as I do a “think aloud.” I will “model” for you the habits of proficient reading so that you can see what good readers do—just the way I was trained to do when I was an elementary school teacher. Then you can go off and practice these skills on your own until you can demonstrate proficiency on today’s standard. Our story today is by David Steiner and Jacqueline Magee.

Making inferences is an important comprehension strategy strongly emphasized in standards and assessments. I infer that Steiner and Magee think the emergence of curriculum as a “pillar of school improvement strategy” in the United States is important, since it says here that in “high-performing systems such as Finland, Singapore, Japan, Hong Kong, and British Columbia….high-quality curriculum is always part of the story.” But they seem to think that just paying attention to curriculum isn’t enough to ensure student achievement. We need to have a sophisticated view of it and look at other factors. The authors describe an “ordinary school examining its 2018 summative student assessment results,” and seeking to address a decrease in student literacy the test reveals. Digging deeper, the school finds that students are “struggling to identify the main idea of a text.” Steiner and Magee describe what happens next: “Armed with their analysis of summative student assessment results, the school develops a plan to explicitly teach the skill of ‘finding the main idea.’”

Good readers make predictions when they read. I predict that explicitly teaching children to find the main idea will raise reading scores. That skill is a key goal of state standards and, in the authors’ example, a weakness the state tests have uncovered. But, wait! Steiner and Magee say the test scores did not improve! Teachers are “disheartened and unsure about what went wrong or what to do next.” But we want schools and teachers to be thoughtful, responsive, and data-driven, don’t we? What’s happening? It says that all the input and feedback this school is getting “encourage[s] teachers to place an unhelpful emphasis on the teaching of these skills.”

The authors seem to be telling us that it’s “unhelpful” because finding the main idea isn’t a skill. But then how are we supposed to teach children to find the main idea? Let’s look for evidence in the text. Here it is! “Good readers can find the main idea of a text when they know how to decode the words on the page in front of them, and when they have the content knowledge to understand the text they are reading.” Notice how I underlined that passage? When we read, it helps our understanding when we highlight and annotate important ideas. The idea that reading “skills” aren’t really skills at all is an important idea to remember. The authors are telling us that once children learn to decode, it’s content knowledge drives reading comprehension.

That’s the main idea!

Good readers “activate their prior knowledge” when they read. I know that David Steiner used to be an ed school dean, New York State’s education commission, and the architect of the widely used EngageNY curriculum; he’s now the head of the Johns Hopkins Institute for Education Policy. That’s a lot of very-high-level experience. And Learning First, which Jacqueline Magee helps run, spreads good practice ideas from high-performing countries all over the world. Therefore we can all infer that states, school districts, policymakers, and people who run teacher preparation programs would be wise to read this paper very closely, just like we’re doing. The authors seem to be saying that American schools are wasting precious instructional time teaching skills and strategies like “finding the main idea.” But, again, let’s look for evidence in the text:

It is up to teacher preparation providers and school systems to support teachers to understand this important point. If these institutions do not cultivate an understanding of the importance of student content knowledge for reading comprehension, and if school systems continue to devise assessments that focus on “skills,” they will encourage the kind of well-meaning but ultimately poor practice described in the introduction to this paper, wasting countless hours of instructional time.

Good readers should be able to restate the main idea in their own words. So let me give it a try: Reading comprehension is not a “skill” you can teach, practice, and master. To understand what they read, children must be taught to decode. But they also need a school curriculum that is broad and rich enough to prepare then to read well on a wide variety of topics. That’s how you create strong readers!

Class dismissed, readers. Off you go!

SOURCE: David Steiner and Jacqueline Magee, “The problem with finding the main idea,” Learning First (January 2019)

The Education Gadfly Show: Teacher strikes, Democrats, and ed reform

On this week’s podcast, Shavar Jeffries, President of Democrats for Education Reform, joins Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss what teacher strikes and Democratic presidential candidates’ support for them mean for education reform. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines whether efforts to boost academic achievement in kindergarten hinder the development of social-emotional skills.

Amber’s Research Minute

Vi-Nhuan Le et al., “Advanced Content Coverage at Kindergarten: Are There Trade-Offs Between Academic Achievement and Social-Emotional Skills?” American Educational Research Journal (January 2019).