Is parental satisfaction enough?

By Michael J. Petrilli

By Michael J. Petrilli

Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from “Is School Choice Enough?,” the lead article in the fall issue of National Affairs.

As with so many issues—from trade and immigration to Russia and taxes—the Trump presidency has exposed a schism within the conservative movement when it comes to education policy. While expanding parental choice is a paramount objective on the right, a key question is whether choice alone is enough, or if results-based accountability ought to be sustained and strengthened, too. How this question is resolved will have wide-ranging consequences—for education reform in general and for the design of school-choice initiatives in particular.

Though it’s easy to lump conservative school-choice advocates into a single category, there are some major disagreements between those who argue for school choice alone and those who wish to combine it with other reform strategies. The first and perhaps the most fundamental of these disagreements can be reduced to one question: Is parental satisfaction enough?

To better understand this question, a simple thought experiment is clarifying: Imagine that conservatives are wildly successful in expanding school choice. Every parent in America, however poor or rich, gains access to several educational options, including religious schools. In a thriving marketplace, these schools compete to attract market share, innovate in ways currently unimaginable, and provide unprecedented levels of customer satisfaction. School choice turns out to be everything conservatives promised it would be.

But what if, with all of that, America’s international rankings in reading, math, and science are still mediocre, or even decline? What if almost 20 percent of our young people still drop out of high school, well over half of those who graduate are still ill-prepared for college-level work, and half of all college matriculants still leave without a degree or credential? What if upward mobility for poor students remains stuck at low levels, and intergenerational poverty remains widespread? Could we really declare victory?

To be sure, plenty of choice advocates contend that it will indeed boost outcomes for students—both those who participate in choice initiatives and those who remain in traditional public schools. But what if that doesn’t happen? Are we really content with customer satisfaction as the measure of our efforts?

If parental satisfaction is all we're after, it shouldn’t be terribly hard to achieve. Polls find that most parents are already happy with their schools. The most recent survey by Education Next, for instance, finds that 62 percent of parents would give their own kid’s present school a grade of A or B.

Yet a closer examination of America’s educational outcomes indicates that our schools are mediocre almost across the board. The math and science skills of our affluent students are middling compared to affluent students in other countries; our children of college graduates do so-so compared to the children of college graduates elsewhere. Everyone talks about the achievement gap in America—between rich and poor students, or white, black, and Latino kids. But there’s another gap, between the lofty perceptions Americans have of their own children’s schools and the objective truth, at least as measured by results.

Why so many parents, including affluent and well-educated ones, are satisfied with schools that provide mediocre outcomes is something of a mystery. Perhaps they want to believe their kids’ schools are better than they actually are to avoid feeling guilty about paying for that kitchen renovation or new SUV instead of private-school tuition. Or perhaps they appreciate other forms of educational excellence—strong sports programs, caring teachers, or engaging extracurricular activities—that don’t necessarily translate into improved test scores, higher graduation rates, and college success. As Jason Bedrick recently wrote, “Parents are interested in more than scores. Parents consider a school’s course offerings, teacher skills, school discipline, safety, student respect for teachers, the inculcation of moral values and religious traditions, class size, teacher-parent relations, college acceptance rates, and more.”

So maybe parents don’t prioritize measurable learning outcomes. But conservatives—indeed all policymakers—should prioritize them. It may be a cliché to say that “children are the future,” but plenty of empirical evidence demonstrates that a well-educated citizenry is more likely to be wealthy and upwardly mobile. Studies by Hoover economist Eric Hanushek, for instance, demonstrate a strong relationship between the cognitive ability of a nation’s population and economic growth. He and his colleagues have estimated that bringing all states’ performance up to the level of Minnesota and other top-performing states would result in an average increase of 9 percent in GDP over the next eight decades, creating trillions of dollars and easily solving America's coming fiscal challenges.

School quality also has an impact on upward mobility. When Raj Chetty and his colleagues examined the likelihood that individuals growing up in poverty would make it to the middle class or beyond, the quality of area schools was one key factor. But what denoted quality wasn’t spending or class size, but test scores.

New studies by Hanushek and his colleagues might explain why. In the United States, the economic “return to skills”—the benefit to individuals in terms of higher pay based on what they know or can do—is higher than in most other advanced nations. Because of our freer economy and lighter labor-market regulations, education really is what helps people get ahead. Assuming that conservatives don’t want to embrace European-style economic models, developing high-level skills is essential for our children. At this point, it should be clear to everyone that Americans with low skill levels are at grave risk of being left behind.

Finally, great schools can even have an impact on family formation. A random-assignment study of career academies by MDRC found that young men who went through high-quality career and technical programs in high school were more likely later to be married and to have custody of their children.

If we care about economic growth, upward mobility, and strong families, we should make improving America’s educational outcomes a priority. Education is both a private good and a public good, and a society has a legitimate interest in the education of its next generation—the more so when public dollars pay for it. Parental satisfaction is an important objective, but far from the only one.

(Photo credit: Getty Images/XiXinXing)

(Trigger warning: This essay contains a bleeped, profanity-laced rant that may cause you to question your most deeply held beliefs.)

It's not often I cite vulgar, inappropriate humor to draw attention to the absurdity that occurs when someone sets achingly low standards and then expects accolades for surpassing them. But I cannot resist after re-discovering a raunchy (NSFW) skit from Chris Rock’s 1996 classic, savagely funny performance in “Bring the Pain”:

You know the worst thing about [bleeps]? [Bleeps] always want credit for some [bloop] they supposed to do. A [bleep] will brag about some [bloop] a normal man just does. A [bleep] will say some [bloop] like, "I take care of my kids." You're supposed to, you dumb [bleeper][bleeper]! What kind of ignorant [bloop] is that? "I ain't never been to jail!" What do you want, a cookie?! You're not supposed to go to jail, you low-expectation-having [bleeper][bleeper]!

I have been wondering how Chris Rock would re-write this skit as we enter the annual season in which a parade of education reform leaders triumphantly announce academic results marginally superior to the poor outcomes of the public education system we have committed our lives to transform.

You know the worst thing about ed reformers? Ed reformers always want credit for some [bloop] they supposed to do!

Take for example Richard Whitmire’s groundbreaking new series in The 74 entitled “The Alumni.” It highlights nine premier charter management organizations. Each network has been operating for nearly two decades or more, and each now can proudly and rightfully claim large numbers of high school graduates who have successfully completed college.

Indeed, rather than the standard dipstick measure of annual state test scores, Whitmire describes a remarkable paradigm shift in the way charter schools define success: “About a decade ago, 15 years into the public charter school movement, a few of the nation’s top charter networks quietly upped the ante on their own strategic goals. No longer was it sufficient to keep students ‘on track’ to college...nor enough to enroll 100 percent of your graduates in colleges. What mattered was getting your students through college.”

Fair enough! Once again, the charter sector would prove its dominance over the status quo and be an exemplar for how public school systems should be held accountable. Understandably, jubilant headlines like this one captured the impact: “Public Charter School Students Graduate From College at Three to Five Times National Average.” Who wouldn’t declare success when the results of these nine networks were compared to the reality that a mere 9 percent of children from low-income families go on to complete college by age twenty-four?

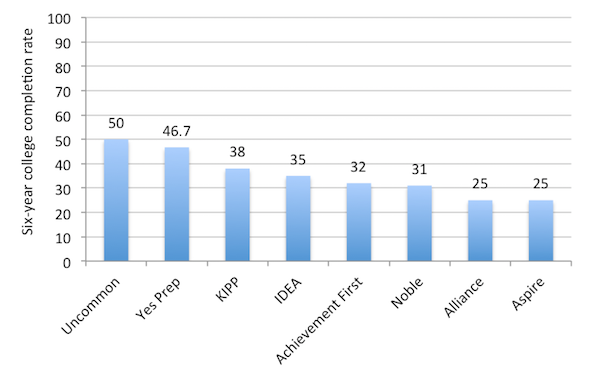

But, as Whitmire acknowledges, we must look closer. Figure 1 depicts the actual college completion rates for eight of the networks he profiles.

Figure 1. Six-year college completion rates at eight top charter networks

SOURCE: Richard Whitmire, “Data Show Charter School Students Graduating From College at Three to Five Times National Average,” The 74 (July 26, 2017).

Across the nine networks, the six-year aggregate completion percentage is 35 percent, not accounting for the size of each network’s student body. Yes, that only 9 percent of low-income students graduate in six years is a crime and a tragedy. But 9 percent is neither an expectation nor a standard. Each of the outstanding leaders of these networks would agree. And they all no doubt aim to have 100 percent of their scholars ultimately earn a degree. So a 35 percent four-year college completion rate in six years is actually an incredibly disappointing absolute outcome, especially for well-established charter networks that produce proficiency rates on state tests far higher than 35 percent.

9 percent? You beat nine percent! What do you want, a cookie?!?

What's more, these completion percentages are likely lower when measured against a more rigorous, accurate standard. For example, in KIPP’s report, The Promise of College Completion, the network emphasizes that measuring college completion accurately begins by tracking “students’ progress starting at the end of eighth grade or the beginning of ninth grade to get a clear picture of KIPP’s impact on our students’ educational attainment. Some educational organizations and reports only measure the college success of high school graduates—an approach that fails to count the students who drop out before earning a high school diploma.” And indeed Whitmire notes that all of the charter networks included in figure 1, except KIPP, do just this.

“Starting counting in 12th grade.” What kind of ignorant [bloop] is that?

Moreover, a four-year degree should take four years to complete, right? Wrong.

The 1990 Student Right-to-Know Act established the nationwide requirement that postsecondary institutions report the percentage of students who complete their program within 150 percent of the normal time for completion (e.g., within six years for students pursuing a four-year bachelor's degree). So the federal government set the six-year time-to-complete measure for consumer information for colleges and universities. But that additional two years represents a significant additional burden of time and money, which could be especially devastating for low-income students. Charters, as the laboratories of innovation within K–12, are neither morally nor legally obligated to use this federally imposed low-bar metric to measure their college completion outcomes.

At Public Prep, for example, the pre-K–8 charter management organization I lead, forty-five scholars started first grade in 2005 when Girls Prep opened as the first and, at the time, only all-girls public charter school in New York City. Because we accepted transfer students—or “backfilled” to replace attrition—throughout the ensuing years in the upper grades, forty-seven Girls Prep scholars actually graduated from eighth grade in 2013. In 2017, an amazing 90 percent of that inaugural cohort of forty-seven graduating Girls Prep scholars were accepted into and will be attending some of the finest colleges and universities in the country, some of which are highlighted below:

Four years from now—not six—we will measure college completion rates for all forty-seven scholars. If we learn that it takes longer for them to earn their degree, then we will work to understand the factors driving the delay and adjust our strategies to help them get closer to on-time completion. But we won't change the measure.

A [bleep] will brag about some [bloop] a normal college student just does. A [bleep] will say some [bloop] like, "My kids graduate in six years." You're supposed to graduate in four years, you dumb [bleeper][bleeper]!

***

College completion rates are not the only area in which standards for comparison are regularly lowballed in the ed reform world. Take for example the obsession among education policymakers to close the racial achievement gap. In July, the National Center for Education Statistics released some “good news” in its report Status and Trends in the Education of Racial and Ethnic Groups. On the 2015 fourth grade NAEP reading assessment, the white-black gap narrowed from thirty-two points in 1992 to twenty-six points in 2015. And the white-Hispanic gap of twenty-four points did not get worse from 1992 to 2015.

Yay? Hardly.

The same NAEP 2015 data revealed that more than half of all white fourth graders—1.25 million white children—are not reading at proficiency, far surpassing any other racial group in raw numbers. Indeed, only 34 percent of all American fourth grade students of all races performed at or above the “proficient” achievement level in reading. Who cares if the black-or-hispanic-to-white achievement gap has barely closed over twenty-three years, if at all, when the majority of white kids can’t read proficiently either and closing the racial achievement gap would simply mean virtually everyone is mediocre?

You're not supposed to just equal low-performing white kids, you low-expectation-having [bleeper][bleeper]!

What’s worse is that myriad states have defined “proficient” to mean something less than college ready. Far too many “proficient” students require remedial courses when they matriculate—and their college completion rates are woefully low compared to their more advanced peers.

This fact is often glossed over, however. Take, for example, the common practice of lumping “proficient” and “advanced” scores on state tests into one consolidated measure. When district and charter schools report proficiency, the percentages are overwhelmingly made up of scholars who fall short of advanced scores. But these higher marks are much more reliably indicative of being on a college ready path.

***

We in the charter sector have to resist the temptation to go along to get along, even if the apparatus of mediocrity surrounding us incentivizes a race to the bottom (or at least just above the lowly status quo). Imagine if we were to take all five of these steps:

If we took this handful of steps, the charter sector would be forced to confront the reality that the vast majority of kids who have been in our schools are not on a path to college completion. Perhaps then we would act with the appropriate urgency to both explicitly name and then address causal factors that truly impede our ability to achieve the academic and life outcomes we know are possible for our kids, such as the decline in family stability and the explosion in multiple births to unmarried women and men age twenty-four and under.

No one who has committed their lives to education reform signed up to measure ourselves against a despicably low standard that represents nothing more than the failed system that we are trying to improve. Achieving student results only marginally better than that low standard also offers no solace whatsoever.

In the must-read bible on college completion, Crossing the Finish Line, the authors describe the students most likely to earn a degree as possessing character traits that “often reflect the ability to accept criticism and benefit from it, and the capacity to take a reasonably good piece of one’s work and reject it as not good enough.” As the charter sector embarks upon its next twenty-five years, leaders should be proud to celebrate the progress we have made and the positive impact we have had on children.

Simultaneously, while we recognize charter school accomplishments as reasonably good, we should reject our work as still not good enough.

Let’s start by ensuring the metrics against which we measure ourselves and our students’ outcomes truly place them on a path to college completion. Let’s shift our focus to absolute results that are aligned with the highest of expectations instead of being continuously shielded by relative comparisons to the pitiful outcomes of a dysfunctional system.

Yeah, that’s what we’re supposed to do!

_________________

Editor’s note: Click here to read part 2 of this article.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

According to the most recent data published by the Office for Civil Rights at the U.S. Department of Education, 27 percent of public school teachers are chronically absent—meaning they miss more than ten days of school for illness or personal reasons.

That’s a lot. But is there an explanation for that number that might satisfy the many critics of our public school system? For example, might it be attributable to the fact that three-quarters of teachers are female, meaning they are more likely to miss work due to maternity and, in most cases, the burden of being primary caregivers?

The short answer is no.

Obviously, teaching is a challenging occupation, especially in high-poverty schools. So the point of this column isn’t that teachers are slackers, or that they should never get a day off, or that no teacher should ever be chronically absent. The point is that there’s room for improvement.

Per OCR, public holidays, professional development days, and field trips don’t count as teacher absences. Nor do summer, winter, or spring breaks. But the data do include days missed for maternity and long-term illness, so let’s crunch those numbers and see where it gets us.

In 2016, approximately 6.2 percent of women ages fifteen to forty-four gave birth. Thus, since the median age of a teacher in the U.S. is forty-one years old, back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that about 3.1 percent of female teachers gave birth that year (and that about 3.1 percent of male teachers spent a lot of time changing diapers).

Although most teachers don’t get paid maternity leave, in most states, their paid sick leave carries over from one year to the next—often with no cap on the total number of days they can accumulate. So it’s likely that most teachers who become new mothers are classified as chronically absent (though that doesn’t explain why we don’t just give them maternity leave).

Of course, teachers are also likely to be chronically absent because of serious, potentially life-threatening illnesses. Unlike the percentage of teachers who give birth, this figure is almost impossible to calculate from scratch. However, according to a recent analysis of data from the National Health Interview Survey, approximately 7.7 percent of U.S. workers with paid sick leave miss ten or more days of work per year due to illness. Since the typical school year is about 20 percent to 25 percent shorter than the typical work year, we might expect that teachers would take fewer sick days than workers in other industries. However, since the typical elementary school is a hypochondriac’s nightmare, let’s assume they need as many sick days as workers in other industries.

Adding the illness-related chronic absenteeism rate for other industries to our estimate of teachers’ childbirth-related chronic absenteeism rate yields a projected teacher chronic absenteeism rate of 10.8 percent. That seems like a humane goal for the education system as a whole, although it fails to account for the shorter length of the typical school year.

Perhaps you think I’m missing something. For example, perhaps you’re wondering whether teachers, because they are more likely to be primary caregivers, are more likely to miss work when one of their own children or a parent is sick. So let me save time by conceding the point: It’s true that I can’t account for everything.

But here’s the thing: The teacher chronic absenteeism rate varies dramatically depending on which district or state you’re looking at. For example, the rate is 16 percent in Utah and 75 percent in Hawaii. And the more you think about it, the tougher it is to see how interstate differences in long-term illness or teachers’ responsibilities as parents (or really anything related to teachers’ demographic characteristics) could explain a difference of that magnitude. Furthermore, the variation in teacher chronic absenteeism is not well explained by student demographics. Nationally, teachers in schools with high concentrations of low-income and minority kids are only marginally more likely to be chronically absent.

Individually and collectively, these observations suggest that the key drivers of teacher chronic absenteeism have more to do with policy than personal circumstance. And, indeed, that’s what I find in a new report that documents the startling teacher chronic absenteeism gap between charter and traditional public schools, as well as the smaller but still significant gap between unionized and nonunionized charters. Nationally, brick-and-mortar charter schools have a teacher chronic absenteeism rate of 10.3 percent, whereas traditional public schools have a teacher chronic absenteeism rate of 28.3 percent.

Some observers will argue that these patterns demonstrate the importance of protecting teachers from exploitation. But this is a tough case to make. For example, traditional public schools in San Francisco, which isn’t known for its abusive labor policies, have a teacher chronic absenteeism rate of just 10 percent.

So are all San Francisco teachers childless? Or, more plausibly, is it reasonable to expect a teacher chronic absenteeism rate of approximately 10 percent? And if 10 percent is good enough for teachers in San Francisco, why isn’t it good enough for teachers in the rest of America?

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in a slightly different form in The 74.

On this week's podcast, special guest Scott Pearson, executive director of the DC Public Charter School Board, joins Mike Petrilli and Alyssa Schwenk to discuss the pros, cons, and challenges of closing low-performing schools. During the Research Minute, David Griffith explores why unionized charter schools in California perform better.

Jordan D. Matsudaira and Richard Patterson, “Teachers’ Unions and School Performance: Evidence from California Charter Schools,” Economics and Education Review (September 2017).

Competition or cooperation? The district-charter school debate has swung back and forth between these alternative strategies since the first public charter schools opened twenty-five years ago. No group has striven harder over that period to find a workable balance than the Seattle-based Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE). Better Together: Ensuring Quality District Schools in Times of Charter Growth and Declining Enrollment is CRPE’s latest effort to bring a moderate, research-based middle-ground to the fraught charter/district relationship that is still too often defined by acrimony, blame, and zero-sum arguments.

Better Together builds on CRPE’s deep expertise in establishing and promoting “District-Charter Collaboration Compacts.” It grows out of the conversation of “more than two dozen policymakers, practitioners, researchers and advocates” that took place at CRPE’s behest in January. Can school districts and charter schools co-exist, even cooperate? Is there a “grand bargain” to be struck that could benefit both sectors while—most important—serving the best interests of students, voters, and taxpayers?

District-charter collaboration is especially challenging in communities with declining student enrollments. In Rust Belt cities like Detroit, Cleveland, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Dayton, the district population has declined by tens or hundreds of thousands of students. Detroit, for example, watched its district enrollment drop from 292,934 in 1970 to less than 50,000 students in 2014, while St. Louis shrank from 113,484 pupils to a paltry 27,017.

Yet these same cities are also home to some of the country’s highest percentages of charter attendees—more than half in Detroit and more than 30 percent in Cleveland, St. Louis, Philadelphia, and Dayton. Not surprisingly, many supporters of traditional districts blame their enrollment woes on charter competition. Never mind that their pupil populations were shrinking before the first charter school appeared.

Facts aside, as one school finance expert observed in Better Together, “Declining enrollment may not be charters’ fault, but it is their problem.” Districts are designed to grow, not contract. Districts face bona fide legacy costs (e.g., building maintenance, debt service, transportation, unfunded pension liabilities, and inflexible teacher contracts) that make it costly and painful to right size.

For example, “last in, first out” contract provisions require that when a reduction in force is necessary, the newest and least expensive teachers must depart—along with their energy and the district’s future work force. This can lead to almost absurd outcomes, such as the time in 2008 when Dayton conferred its “Teacher of the Year” award at the same time the recipient was handed his pink slip. This hurt not only the Dayton Public Schools, but also Dayton children who lost a top-notch teacher to a far less needy suburban district.

State policies also make it hard for districts to shrink—and for charters and districts to collaborate. As one district official put it in Better Together, “These problems are often exacerbated by state funding formulas that don’t adequately reflect enrollment changes, are outdated, or at times simply are ‘bizarre.’” Further, “In many places, they often pit charter schools against district schools, either by providing different per-pupil funding formulas or ignoring stickier ‘legacy costs.’”

In some states, conservative lawmakers are simply fed up with urban districts (and their liberal voters) that spend $20,000 or more per pupil but never deliver results. On the flip side, teacher union opposition to charters make it impossible in some communities for charters and districts to even hold a civil conversation, much less work together.

While Better Together focuses on the challenges facing urban districts and charters, the experiences and positions that it surfaces apply to rural communities, too. In Gooding, Idaho, population less than 1,400, a charter school opened in 2008 and 10 percent of the district’s pupils shifted into it during a single summer. This precipitated brutal fights in Gooding and in the Boise statehouse, with one side claiming that the charter would bleed the district of essential resources and the other saying that children needed education options and opportunities that the district couldn’t (or wouldn’t) provide. Rural districts and their charters need to figure out how to work better together as much as do those in declining metropolises.

Better Together offers some “first steps towards solutions” that are relevant to urban and rural communities alike. These include:

Some of the proposed solutions in Better Together are already being field-tested. For example, the 2012 Cleveland Plan for Transforming Schools (based in large part on CRPE research) created a Transformation Alliance that seeks to ensure that all new charter schools in the city are high quality. It scrapped rules making seniority the deciding factor in teacher layoffs, and it authorized the district to share local levy dollars with high-performing charters.

There’s much debate about how well this is working in Cleveland—and it’s not going to be easy anywhere. Better Together is honest about the challenges that such efforts face in places with shrinking populations. But it also makes a strong case for how communities and children benefit when school districts and charters work together.

SOURCE: Better Together: Ensuring Quality District Schools in Times of Charter Growth and Declining Enrollment, Center on Reinventing Public Education (September 2017).

Terry Ryan is the CEO of Bluum, an Idaho-based school reform organization. For ten years he led Fordham’s education reform efforts in Ohio.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

This study uses administrative data and other public records to examine the impact of unionization on the test-based achievement of California charter schools between 2003 and 2013. Using a difference-in-differences approach, the authors estimate that unionization boosted math achievement by about 0.2 standard deviations but did not significantly affect reading achievement. These estimates differ from those of Hart and Sojourner (2015), who analyzed similar data but found that unionization had no impact on test scores. However, in the appendix of the more recent study, the authors provide a mostly convincing defense of their methodological choices.

A quarter of California charters were unionized in 2013, and between them these schools accounted for a third of charter enrollment. However, for obvious reasons, the authors exclude “conversion” charters that are automatically unionized because they are legally bound to the district contract. So their analytic sample includes just forty-four charter schools that switched from non-unionized to unionized between 2003 and 2013.

Overall, students in unionized charters score about 0.5 standard deviations higher on math and about 0.3 standard deviations higher in reading than students in non-unionized charter schools. And teachers in these schools are more experienced and far more likely to be on track for tenure than those in non-unionized charters. Yet relative to non-unionized charters, “switchers” have lower test scores, more minority and English Language Learner students, and are unusually concentrated in large urban school districts. (Nearly half are located in Los Angeles, Oakland, and San Diego.)

As the authors note, unions might improve school performance in a number of ways. For example, they might attract better teachers (via higher wages), reduce teacher turnover, and boost “teacher voice” (thereby improving the flow of information within a school). However, they might also do harm insofar as they prevent administrators from rewarding high-performing teachers or terminating underperforming teachers, and insofar as they engage in rent-seeking behavior.

But this is just speculation; one weakness of the study is its inability to account for the mechanism through which unions may boost achievement. For example, the authors estimate that unionization leads to a 0.8 year decline in teacher experience but has no effect on class size, the share of teachers with a master’s degree, or the fraction with a tenure-track position (none of which makes very much sense).

Another major question mark is the degree to which the study’s findings are generalizable. After all, unionization doesn’t occur in a vacuum. So it’s possible—perhaps even likely—that working conditions and administrators at the schools in question were below average. Thus, even if the authors have succeeded in isolating the impact of unionization for these schools, it doesn’t necessarily follow that every charter would be higher-performing if it unionized.

In short, the study suggests that voluntary unionization is potentially beneficial for low-performing charters. However, when it comes to high-performing charters—not to mention traditional public schools, where both theory and experience suggest that unionization may be more problematic—there are still plenty of reasons to be skeptical.

SOURCE: Jordan D.Matsudaira and RichardPatterson, “Teachers’ Unions and School Performance: Evidence from California Charter Schools,” Economics of Education Review (September 2017).