The case for Sonja Santelises as the twelfth U.S. Secretary of Education

When it comes to education and the incoming Biden administration, all eyes are on who is put forward, likely before the year is out, as the next secretary of education.

When it comes to education and the incoming Biden administration, all eyes are on who is put forward, likely before the year is out, as the next secretary of education.

When it comes to education and the incoming Biden administration, all eyes are on who is put forward, likely before the year is out, as the next secretary of education. The deluge of desired traits and deserving names has been disorienting, prompting former secretary Arne Duncan to quip, “We’re looking for someone who walks on water.” It’s hard to see how anyone can completely fulfill the demanding job requirements, but assuming the role’s emphasis will continue to be on K–12, there’s one candidate who stands above the rest: the current CEO of Baltimore City Schools, Dr. Sonja Santelises.

Setting aside the recent attacks on her qualifications, which alone sets Santelises apart with her degrees from three Ivy League institutions, and her considerable experience working in and leading urban school systems, the larger consideration is selecting someone who can transcend divides and embody President-elect Biden’s admirable promise to be a unifying leader. For Democrats, there’s also an expectation that the next secretary is a current or former teacher and, based on the rumored short list, has teachers union ties. For Republicans, it’s hard but not impossible to see how a union apparatchik wouldn’t be DOA in a GOP or barely Democratic-controlled Senate. But Republicans should be interested in an education secretary who shares common cause in asking hard questions about what America’s students are actually learning in school. One would be hard pressed to find a prospect better than Santelises in marrying these disparate interests.

During her two tenures in the tumult of Charm City, previously as chief academic officer and now as CEO, Santelises has been a stabilizing force and a tireless advocate for high-quality curricula as a fundamental driver of change. Under her leadership, the district undertook an extensive audit of its instructional materials and found that its curriculum had more holes than a block of Swiss cheese—a troubling pattern that amounted in Santelises’ memorable phrase to “educational redlining.” She writes:

For example, our more than 80,000 students—80 percent of whom are Black—were taught about tragedies of African American history such as slavery and Jim Crow but learned nothing about the Great Migration and very little about the Harlem Renaissance. Our students didn’t learn about the systems of the human body until ninth grade. Some students didn’t learn about decimals until after they were tested for our gifted and talented program, meaning they couldn’t gain access to enriched classes. And in history, they learned much about the Civil War but little about the American Revolution.

This heartbreaking discovery brought about a complete system overhaul, followed by an “unusually strong” increase in standardized test scores. To be sure, pass rates in the district remain remarkably low, but Santelises appears to be onto something that is far too often overlooked in America’s schools: the critical role knowledge plays as a building block for good instruction.

A Secretary Santelises would have no formal jurisdiction over curriculum in the nation’s 13,000 school districts, but what she would lack in conferred authority would be more than made up for with her influence, credibility, and her charisma of competence. Previous secretaries have focused on structural changes to our nation’s schools (e.g., school choice, integration, teacher quality), but Santelises would be an intriguing selection if she took her priority of improving classroom instruction to a larger stage. Used appropriately and judiciously, the secretary’s convening power and bully pulpit in Santelises’s discerning hands could encourage state and district leaders to begin paying more attention to the black box of classroom instruction. What if, for example, she convened the former education secretaries along with key state and district leaders—think Bush 41’s 1989 Charlottesville education summit—to hear from E.D. Hirsch, Jr. or Daniel Willingham and discuss the value of shared knowledge to both individual success and societal well-being? The federal government can’t get directly involved with curricula, but it could help connect states with content experts and provide opportunities for peer learning and collaboration.

What’s more, the stars could be aligning for curriculum reform and Santelises. As ed reform and our national discourse has become more polarized, rich and engaging content could be one of the few remaining areas of shared real estate between Democrats and Republicans for seeing eye-to-eye on education. As stated well by my colleague Robert Pondiscio:

There is a story, and it’s about curriculum—perhaps the last, best, and almost entirely un-pulled education reform lever. Despite persuasive evidence suggesting that a high-quality curriculum is a more cost-effective means of improving student outcomes than many more popular ed reform measures, such as merit pay for teachers or reducing class size, states have largely ignored curriculum reform.

If following science is as important to Biden as he says it is, few state or district superintendents are more well-versed or more committed to knowledge-rich curricula and the science of reading than Santelises.

On the question of charter schools and choice, Santelises is less strident than die hard enthusiasts or critics might prefer. Baltimore City has over 900 students participating in Maryland’s voucher program, as well as the largest number of charter schools in the state. It would be easy to scapegoat one or both sectors in light of the district’s declining enrollment numbers, but Santelises welcomes the competition. As she told a local radio host, “We know families are going to make different choices. We [the district] want to be in the running.”

Today’s extraordinary circumstances also call for an education secretary who has been on the front lines of the pandemic and is clear-eyed about what our schools and students are facing, especially those living in our most marginalized communities. Of the many times I’ve heard her speak or engaged with her otherwise, I’ve found Santelises’s combination of thoughtfulness and straight talk to be a refreshing contrast to the banal platitudes and syrupy praise that are all too pervasive in this line of work.

Shortly after taking the reins in Baltimore, Santelises said, “I’m not a savior. I’m not stupid enough, or naive enough, to think I know everything or that I can save anybody. I’m just here to do the work.” No one can walk on water, but Santelises has been a rainmaker for her students, and one who refuses to get caught up in adult issues. Her roll-up-your-sleeves ethic is something that liberal and conservative leaders alike can embrace. Biden’s team would do well to keep Santelises top of mind as they weigh their options.

At the tail end of a recent symposium titled “Why children can’t read—and what we can do about it” hosted by American Enterprise Institute, Margaret Goldberg, a California first grade teacher and founder of the Right to Read Project, made a simple and surprising observation. As a teacher, she feels that her most important job is to teach reading. But that’s not the message she and other elementary educators are hearing.

“I hear that my primary job is to meet the social and emotional needs of my students, or it’s to have strong classroom management, or unpack my implicit bias. It’s to make sure that they have rich art experiences, or do exploratory learning. I’m told a thousand different things that I’m supposed to focus on,” she explained. “I think if we gave teachers permission to focus on teaching reading well, and gave them the supports that they need, we could actually get somewhere with this problem.”

If you’ve never been in the classroom, hearing a first grade teacher say she’s told that her success is judged on things other than teaching reading must sound like telling an air traffic controller she has things to do that are no less important than safely landing planes. But a lot of teachers are going to suffer neck strain nodding along with Ms. Goldberg whose remark wasn’t pointed or combative. It was a simple, just-the-facts-ma’am observation for the benefit of AEI’s audience of policy wonks.

So listen to Ms. Goldberg. If we’re serious about raising reading achievement (is there anything more important for early childhood education?) the best place to start is by clearing away the weeds and signaling to pre-K and elementary school teachers that their primary job is to teach reading. Since nearly every bad outcome in education has its roots in early reading struggles, everything else matters less.

This is not a decision teachers can make unilaterally. Assessment expert Dylan Wiliam regularly counsels school leaders and administrators to take things off of teachers’ plates, not add more. “The thing you take off will be a good thing,” he notes, but “stopping people doing good things gives them time to do even better things.” In other words, schools and teachers need a permission structure to focus on early childhood literacy. That’s the role of policymakers to create and enforce.

Some states see and embrace this priority more than others. At the same AEI event, Carey Wright, Mississippi’s State Superintendent of Education, described the steps her state has taken to prioritize early childhood literacy, notably the state’s “Literacy-Based Promotion Act,” which requires schools to retain students in the third grade who score at the two lowest levels on state reading assessments. Even more important are requirements that the state’s teachers must be trained on the science of reading. A 2016 Mississippi law requires elementary education candidates to pass “a rigorous test of scientifically research-based reading instruction and intervention.” This puts the onus on the state’s ed schools to ensure teacher candidates know and can implement effective instructional practices to teach reading.

Equally critical was the decision to deploy literacy coaches, who work for the state, not schools or districts. “That may not sound like much, but the last thing I needed was to push money out to districts and have us have a principal on the other end say, ‘Oh, thank God. I can get rid of this lousy fifth grade teacher,’” Wright tells me. “I’ll make him the literacy coach and use this money to hire a good teacher.’”

It’s seldom observed that the vast majority of American teachers are trained and certified in the states in which they work. This gives state policymakers a prodigious amount of leverage both to insist that colleges of education stress the science of reading in training early elementary educators, and to ensure that state certification reflects candidates’ ability to implement it. “I’m not sure that all states are taking advantage of the authority that we have,” Wright observed. “We made a decision that all teachers K–three, and all administrators and special ed teachers, were going to be required to have the training. We just made the decision. We didn’t ask anybody’s permission.”

Mississippi is not the only state with a third-grade reading guarantee, or that has taken steps to signal the importance of the science of reading. Arkansas’s 2017 “Right to Read” Act requires K–6 teachers, K–12 special educators, and reading specialists to obtain a “proficiency credential” on the science of reading. Tennessee requires teacher prep programs to align their programs with sound literacy practices. Watch for an upcoming report from the Council of Chief State School Officers that will detail these and similar initiatives in other states.

It’s a bit of a bromide to say that policymakers need to “listen to teachers.” But listen to Margaret Goldberg. Early childhood and elementary school teachers have no more important task than to teach reading. And policymakers have no more important role than to create the permission structure for teachers to focus on getting children to the starting line of basic literacy. Everything else is less important.

No, seriously. Everything else is less important.

Nothing better evokes education reform’s predicament today than what occurred in late July when the National Basketball Association restarted its 2020 season. Players were given the option of featuring on the back of their jerseys one of about thirty messages. At least eleven players chose “Education Reform.”

Education reform has moved to the multimillion-dollar athlete from intrepid but impoverished policy wonks and reform advocates. We’ll see if that’s a welcome move. But the anecdote reflects a serious dilemma for the education reform movement: It’s become the equivalent of an athlete’s tagline with uncertain meaning.

Symbolism aside and truth to tell, much of the political dysfunction and gridlock that besets our lives today characterizes the education reform movement, too. Pundits from the left and right have recently declared the end of the more or less three-decades-long center-left/center-right coalition that advanced issues like standards, testing, accountability, teacher evaluation, and charter schools. That coalition has decoupled.

I’m not ready to give up. I believe a renewed coalition can be created that unites former members with fresh allies to revitalize education reform. The need for reform is still great. While some progress has been made, learning gaps between White and minority students remain, achievement trends have flattened in some domains, and the pandemic has brought on its own learning losses.

This project should be based on an opportunity framework with a social capital perspective. Its goal is for every American, regardless of age, color, gender, etc., to develop and deepen habits of mind and of association that build their capacity to pursue opportunity and a prosperous life.

This approach asserts three broad value propositions that I take to be centrist and potentially bipartisan, even nonpartisan, when applied to educating young people. First, knowledge and networks are essential to preparing people to access opportunity. Second, local initiatives and mediating institutions, including the familiar (if tattered) organizations of civil society, are crucial to creating coalitions and lasting programs. Third, preparing young people for adult life, work, and citizenship includes cultivating an occupational identify and vocational self.

I base my proposal on Joseph Fishkin’s notion of opportunity pluralism and offer two examples, chosen to illustrate the framework’s applicability to a current education policy issue: career pathways programs that link students and schools with employers and work. I conclude with reflections on how this approach contributes to a young person’s development of an occupational identify and vocational self.

Opportunity pluralism

University of Texas law professor Joseph Fishkin has written on how opportunities are structured and accessed by individuals, including how education’s credentialing process for work and career contains bottlenecks that deter opportunity. He argues for opportunity pluralism, a structure that offers individuals multiple education, training, and credentialing pathways to work and career. They include but are not limited to the four-year college degree. Instead of struggling to equalize opportunity on a single pathway, Fishkin contends, the range of opportunities for individuals at all life stages must be broadened and deepened.

The institutional opportunity structure includes at least four education and training sectors—K–12, postsecondary, workforce training, and employers. Each plays a significant role in developing diverse pathways that connect individuals and schools with employers and work.

An opportunity framework

The framework combines what students know—knowledge—with whom they know—relationships. It recognizes the cultivation of habits of mind and of association as building blocks of individual opportunity.

Habits of mind are the basis for an individual’s hope that he or she can shape future circumstances and comprise three modes of thinking. They include goals thinking (defining and setting achievable outcomes), “pathways-thinking" (creating a route to these outcomes), and agency-thinking (pursuing goals and pathways through personal agency and self-efficacy). Pathways- and agency-thinking together foster the pursuit of goals, helping individuals overcome the obstacles that life will place before them.

Habits of association involve the accumulation of two kinds of social capital: the “bonding” kind and the “bridging” (or “leveraged) kind. Bonding social capital occurs within a group, reflecting the need to be with others and thereby obtain emotional support and companionship. Bridging social capital occurs between social groups, reflecting the need to connect with individuals different than ourselves, expanding our social circles across features like race, class, and religion. Bonding and bridging social capital are complimentary. As Xavier DeSousa Briggs says, binding social capital is for “getting by,” and bridging social capital is for “getting ahead.”

Analysts from the left—e.g., Robert Putnam—and right—e.g., J.D. Vance—affirm the importance of social capital in the lives of individuals, local communities, and the nation. This notion has a long history of support from a variety of ideologically diverse analysts, going back in recent times to James Coleman and his work on adolescents and schools. For this reason, the network approach to social capital and opportunity has the potential to unite divergent political orientations and beliefs.

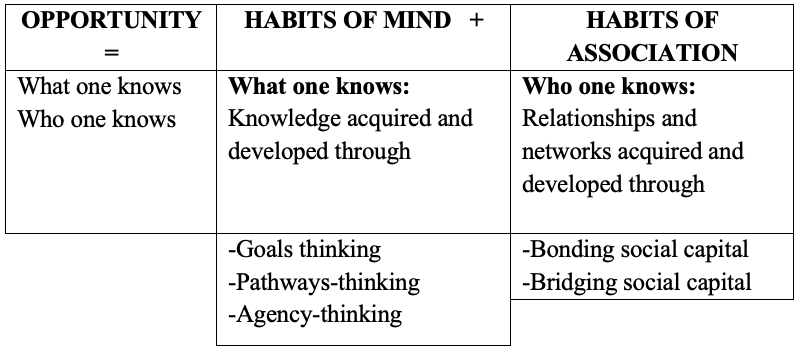

This figure illustrates the main elements of an opportunity framework, as showing in Table 1.

Table 1. An opportunity framework

In shorthand: Opportunity = Knowledge + Networks.

Opportunity requires a judicious combination of what and who one knows. What one knows entails habits of mind focused on learning content knowledge using several modes of thinking. Who one knows involves habits of association focused on relationships and networks developed through the two modes of social capital.

They are habits insofar as they encompass patterns of conscious behavior and responsible conduct learned and internalized through practice. They are also moral strengths whose responsible exercise leads to virtuous behavior—i.e., developing an individual’s talents to full potential and increasing that person’s life opportunity and worthy citizenship.

Examples

Such a framework can help K–12 schools foster knowledge and networks via activities such as student-employer apprenticeships and internships; career and technical education; dual enrollment in high school and postsecondary institutions; job placement and training; career academies; boot camps for acquiring discreet knowledge and skills; and student staffing and placement services.

Here are two illustrations initiated by state governors of different political parties.

Delaware Pathways was initiated in 2014 by Democrat Jack Markell to provide college and career preparation for youth in grades seven to fourteen. Its goal was to create pathways from school to careers aligned with state and regional economic needs, especially for middle skills jobs.

Middle school students learn about career options and then, as high school sophomores or juniors, take career related courses. High school students can take college classes at no cost to families, serve as interns, and earn work credentials. Beginning in the summer before senior year, students participate in a 240-hour paid internship that lasts through the year.

The program engages K–12 educators, businesses, post-secondary education, philanthropy, and community organizations. For example, Delaware Tech is the lead agency that arranges work-based experiences. United Way coordinates support service for low-income students. Boys and Girls Clubs and libraries provide after school services.

Currently, Delaware offers pathways in fields like advanced manufacturing, engineering, finance, energy, CISCO networking, environmental science, and health care. Over 9,000 students are enrolled, around 45 percent of the state’s high school students. Many also take career related courses at institutions of higher education and earn credit that can be applied to associates degree or certificates.

On the Republican side, Tennessee’s Bill Haslam created the Drive to 55 Alliance in 2015, a partnership between the private sector and nonprofits intended to equip 55 percent of Tennesseans with a college degree or training certificate by 2025. Its five programs, three pertaining to K–12, create partnerships among school districts, postsecondary institutions, employers, and community organizations.

First, Tennessee Promise Scholarship provides last-dollar support for high school graduates attending community or technical colleges, including linking Promise students with private sector volunteer mentors and nonprofit partners.

The second program is Tennessee Reconnect, a counterpart to TN Promise, offering a last-dollar grants for adults to earn an associate degree or technical certificate, tuition-free.

Third, Tennessee Pathways promotes a college and career approach to K–12 schools and grants a Department of Education pathways certification to programs with strong alignment among high school programs, postsecondary partners, and regional employment opportunities.

Next, the SAILS program is for high school students who did not reach the ACT college readiness benchmarks in mathematics. It provides in-person and online learning so students can complete math modules for postsecondary credit so they don’t need remedial math in college.

Finally, Tennessee Labor Education Alignment Program or LEAP is directed to four-year post-secondary institutions. It links them with employers so colleges can offer programs aligned with actual employer workforce needs.

Linking all these programs together is an online portal called CollegeForTennessee, providing planning tools for career and college for students, counselors, and educators.

Opportunity pluralism and a vocational self

All this is about providing young people with new ways to acquire habits of mind and association that develop an occupational identify and vocational self. This includes placing student knowledge acquisition, engagement, and networking at the center of program design. Developing knowledge and awareness of oneself as a worker within the broader sense of one’s abilities, personality, and values is an important foundation for adult success and a lifetime of opportunity.

Such programs also use developing habits of mind and association that lead to a vocational self—e.g., apprenticeships, internships, boot camps, income share programs, staffing and placement services, etc. They create new ways that K–12 education and partner organizations develop an individual’s talents to his or her full potential, increasing that person’s ability to pursue opportunity over a lifetime.

They exemplify what Ryan Craig calls “faster and cheaper” pathways to jobs and careers than is generally possible in traditional education settings. And they take a pluralistic approach to accessing opportunity—i.e., they create a range of pathways to opportunity and lifelong well-being.

Such a framework could rekindle an expanded reform coalition of diverse policymakers, advocates, and other stakeholders who believe expanding opportunity for young people includes developing their knowledge and networks. If we can’t come together in pursuit of that mission, it will not only show lack of will. It will also reveal a lack of imagination on how to unite different factions of the education reform movement under a core set of values.

A perennial complaint about holding students accountable through grades and test scores is that these mechanisms are biased against already disadvantaged students. This narrative may ultimately harm the students it is meant to defend, since research has shown that students can up their game when challenged and students learn more when taught by teachers with higher academic standards.

Since even advocates for abolishing A-to-F grading are typically realistic that some form of grading will continue for the foreseeable future, it is worth considering how we can expel racial bias in the grading system. That’s where a new study by David Quinn, a researcher at the University of Southern California, adds important new insight. Professor Quinn uses experimental data to examine how different grading practices may limit or exacerbate teacher bias.

But first, are teacher grading practices actually biased?

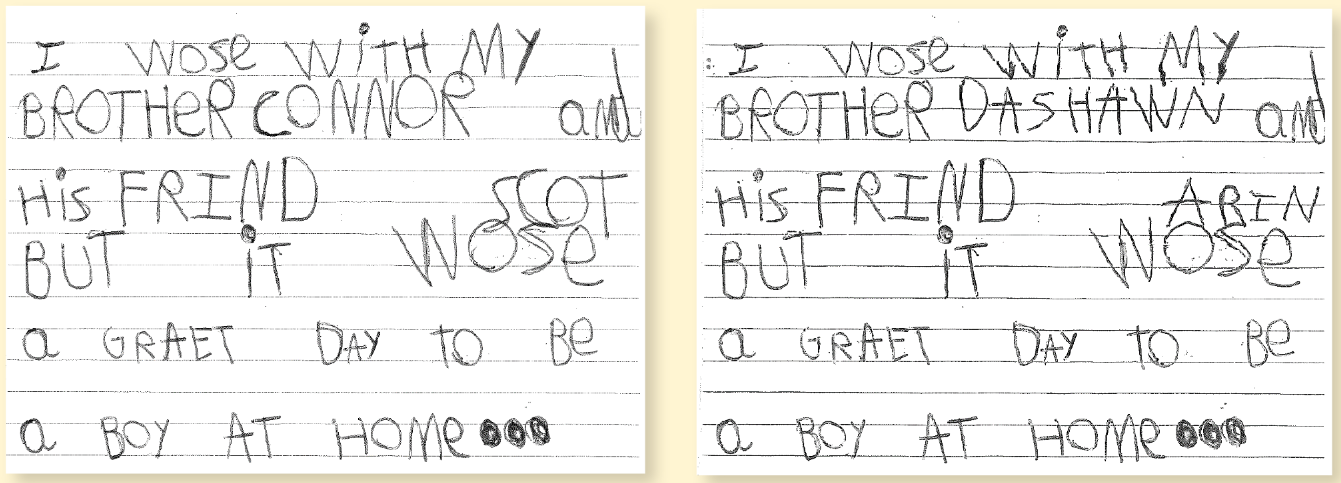

The methodology of this paper enables an answer to this question by isolating teacher racial bias in a clever way. Teachers graded sample assignments that were purportedly completed by real second grade students, but, as with previous studies on implicit bias, the artifacts that were rated by the teachers were carefully constructed by the researchers to be identical in every way except a reference to a name that subtly signals the student’s race. In a similar study of racial bias in callbacks for job interviews, the researchers sent out identical resumes, except for random alternation between “White” names like “Brendan” and “Black” names such as “Jamal.” In the present study, the fictional second graders wrote about their weekend, referencing their brother, whose name was either “Connor” or “Dashawn,” with the race-signaling names randomly assigned to different teachers by the researchers (see Figure 1).

Unfortunately, the study finds strong evidence of grading bias against Black students. White teachers who graded the work of “Deshawn’s” brother were considerably less likely to rate it at grade level than those who graded the work of “Connor’s” brother, despite the fact that the two assignments were identical. Women teachers also exhibited this bias, while teachers of color and male teachers did not exhibit bias towards the fictional Black student’s assignment. Disturbingly, those working in the most diverse schools were the teachers whose answers had the greatest grading disparity.

Figure 1: The writing samples are identical except for the race-signaling names

Source: David M. Quinn, “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading,” Education Next (November 2020).

Thankfully, the study doesn’t end there. The teachers were also asked to grade assignments according to a detailed rubric. When grading according to the rubric, teachers exhibited no racial bias, with virtually identical ratings for the two assignments. This finding held among teachers in general, as well as among White and female teachers and those working in relatively diverse schools.

The study’s main strength—the anonymous grading of papers by fictional students, which enables the researcher to isolate the effects of race—is also a weakness, since it is unclear if teachers exhibit the same levels of implicit bias against students in their classrooms, whom they presumably know well. And because the study focuses on grades at the elementary level, where grading is lower-stakes (no one puts their elementary school grades on their college application), it is less clear what impacts these biases have. The author is aware of and admits these drawbacks, but they are worth restating here.

Still, the suggestion to use strict rubrics when grading is welcome, since clear grading criteria are fairer to students and help ensure uniformity of standards. Of course, it is not feasible to use such rubrics in every subject or for every assignment, since, for example, a creative writing assignment may require the student to color well outside any rubric’s lines. But for many types of assignments, clear rubrics help. In higher grades, “blinding” student work by removing identifying information prior to grading can also help teachers to avoid not just potential racial or gender bias, but also bias against specific students about whom they have already formed opinions.

Removing bias from grading is doubly beneficial. Not only are grades more accurate and, thus, more legitimate signifiers of academic merit, but students who may be unfairly disadvantaged by some grading practices can be surer that they are on an equal playing field with their peers.

Reviewed: David M. Quinn, “How to Reduce Racial Bias in Grading,” Education Next (November 2020); based on David M. Quinn, “Experimental evidence on teachers’ racial bias in student evaluation: The role of grading scales,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 42, no. 3 (2020): 375–92.

In policy circles, school choice and desegregation discussions often stop at the schoolhouse door. But a timely new book edited by a high school senior from Columbus goes inside the gates, and should be essential reading for anyone working in education at any level.

Black Girl, White School is a strong reminder that the students who attend charters or private schools aren’t just statistics or dollar amounts, but real people who are willing to leave familiar terrain in pursuit of a better education. Given the segregating nature of school district boundaries, such decisions often mean that students of color attend predominantly White institutions (PWI). Such is the case for the book’s editor Olivia V.G. Clarke, as well as the volume’s other contributors, who range from fellow high schoolers to college students to young adults who are now part of the working world.

Clarke herself seems to have thrived at Columbus School for Girls (CSG), a highly-regarded, secular, independent, K–12 private school. She will graduate a year early thanks to the availability of academic acceleration. But as the book’s subtitle suggests, academics often take a backseat to racial dynamics. According to GreatSchools, CSG’s student body is 31 percent non-White, but Clarke often felt that she was the “token” Black student, and therefore required to represent all Black people to White students and teachers. In one of many letters to her younger self, Clarke writes: “Suddenly and often unfairly you become a representative for all people of your ethnic background.” Various other contributors express similar experiences. “In the transition from public middle school to the private, predominately white school you currently attend, you lost everything you once knew…,” high school junior Aminah Aliu writes. “In the classrooms where you were the only Black girl—the only Black person—you felt betrayed by the school that let you in but didn’t know how to keep you from falling apart.” From slavery to desegregation to Black Lives Matter, these young people—trying to learn history and civics too, don’t forget—found themselves being used as the filters through which White adults and peers explored difficult and complex topics.

Unfortunately, being asked to “do the work” of representing Blackness for the benefit of White adults and peers was one of the more benign struggles described. Obsessions with students’ hair, skin, and names abound in the book’s essays, poems, and reflections. The authors recount rude questions, intrusive requests, and numerous slights from White kids and g alike. And worse. “I don’t see why you’re worried about getting into college,” begins an unwanted comment recalled by Lydia Patterson in her freshman year at “the bougiest private school” in Houston. “You have affirmative action… You know that’s the only reason you’re here, right?”

An interesting facet of these memoirs is a tonal difference based on age. Pieces from the youngest contributors are often characterized with questions—they wonder if they brought such attention onto themselves by their actions or words, and they long to figure out how to simply exist and learn without so many people watching their every move. “Some will ask why your hair is not straight like theirs,” warns Marissa Glonek to other Black girls following in her footsteps. “Some will stare at you in history class to gauge your reaction to slavery.” The oldest contributors’ pieces are set off from the others by text and design—titled “Thrive Tips”—forming a sort of chorus of affirmation in response to the younger students’ questions. The gist of their reflections is “we survived this, and so can you.” In fact, Clarke herself seems well on the way to turning that corner. Knowing that in the past, she didn’t always feel comfortable to fully be herself, she writes to her younger self: “Take pride in what you have. Take pride in your gorgeous hair and your beautiful melanin. You are enough. You’re beautiful.”

There are plenty of important takeaways from this book. But the biggest is that it shouldn’t be this hard for students of color who seek a new and better learning environment. It is completely awesome that Olivia V.G. Clarke and her peers have taken the initiative to band together and support each other to and through PWI’s. But it would be far more awesome if the staff and students in these schools offered unconditional welcomes and fewer questions and thoughtless comments. There are more and more students of color coming behind Clarke. Policymakers and school leaders must remember that real students are uprooting themselves in search of a better fit. They need more thriving, less just surviving, and no more requests to touch their hair.

SOURCE: Olivia V.G. Clarke, ed., Black Girl, White School: Thriving, Surviving, and “No, You Can’t Touch My Hair”, Lifeslice Media (Columbus, Ohio), 2020.

On this week’s podcast, ExcelinEd’s Matthew Joseph and The Education Trust’s Zahava Stadler join Mike Petrilli and David Griffith to discuss how states can protect schools and disadvantaged students from budget cuts. On the Research Minute, Victoria McDougald examines the effects of absenteeism on cognitive and social-emotional outcomes.

Lucrecia Satibanez and Cassandra Guarino, “The Effects of Absenteeism on Cognitive and Social-Emotional Outcomes: Lessons for COVID-19,” retrieved from Annenberg Institute at Brown University (October 2020).

If you listen on Apple Podcasts, please leave us a rating and review - we'd love to hear what you think! The Education Gadfly Show is available on all major podcast platforms.