College preparedness over the years, according to NAEP

The benefit of different post-diploma paths. Michael J. Petrilli and Chester E. Finn, Jr.

The benefit of different post-diploma paths. Michael J. Petrilli and Chester E. Finn, Jr.

For almost a decade, the National Assessment Governing Board, which oversees the National Assessment of Educational Progress, studied whether and how NAEP could “plausibly estimate” the percentage of U.S. students who “possess the knowledge, skills, and abilities in reading and mathematics that would make them academically prepared for college.”

After much analysis and deliberation, the board settled on cut scores on NAEP’s twelfth-grade assessments that indicated that students were truly prepared—163 for math (on a three-hundred-point scale) and 302 for reading (on a five-hundred-point point scale). The math cut scores fell between NAEP’s basic (141) and proficient (176) achievement levels; for reading, NAGB set the preparedness bar right at proficient (302).

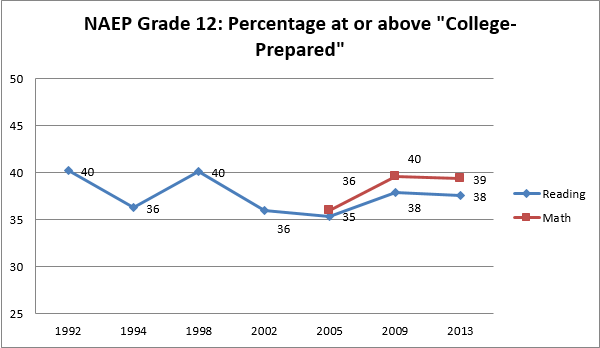

When the 2013 test results came out last year, NAGB reported the results against these benchmarks for the first time, finding that 39 percent of students in the twelfth-grade assessment sample met the preparedness standard for math and 38 percent did so for reading.

These preparedness levels remain controversial. (Among other concerns is the fact that the NAEP is a zero-stakes test for students, so there’s reason to wonder how many high school seniors do their best on it.) But NAEP might in fact be our best measure of college preparedness because, unlike the ACT, SAT ACCUPLACER, or Compass, it is given to a representative sample of high school students (at least those who make it to the twelfth grade). That doesn’t make it perfect, but it’s more revealing than the alternatives with regard to the population as a whole.

That was 2013. But what about over the long haul? We decided to use NAEP to track college preparedness over the past two decades. This was easy for reading, since the “prepared” level is set at the same point as “proficient”—and it’s a breeze to find the percentage of students at or above proficient since 1992. Math was harder both because its cut score fell between “basic” and “proficient” and because a new test and scale were introduced in 2005. We owe special thanks to the National Center for Education Statistics, which calculated the results for math that are displayed below using restricted NAEP data.

Here’s what we found—the trends for “college preparedness” over time—since 1992 for reading and since 2005 for math:

The main storyline is consistency. The rates have bounced between 35 and 40 percent; they are currently up a bit since a low point in 2005. Considering that U.S. high school graduation rates are also up significantly over this period—and thus a greater portion of students are reaching the twelfth grade—these are mildly encouraging trends, despite the overall flatness of the lines.

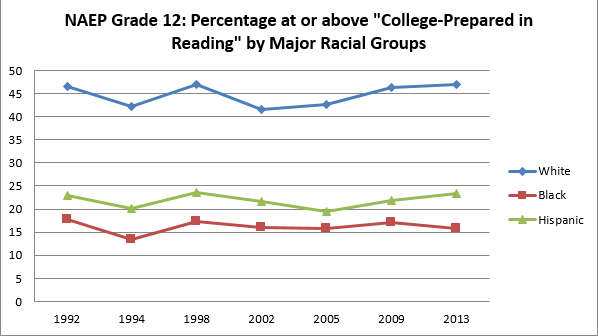

Furthermore, the (mostly) flat lines are not due to “Simpson’s Paradox.” In education, that phenomenon explains why some aggregate trend lines look flat or worse, even though every student subgroup is improving, because of the changing demographic composition of the total student population (e.g., lower-scoring Latino students are gradually replacing higher-scoring white students). In this case, though, each of the three main subgroups shows basically the same flat trends:

Nobody should celebrate the fact that fewer than 40 percent of high school seniors are academically prepared for college-level work. (ACT shows similar “readiness” proportions for those who take its high-stakes test.) But why do we have the sense that this problem has worsened over time?

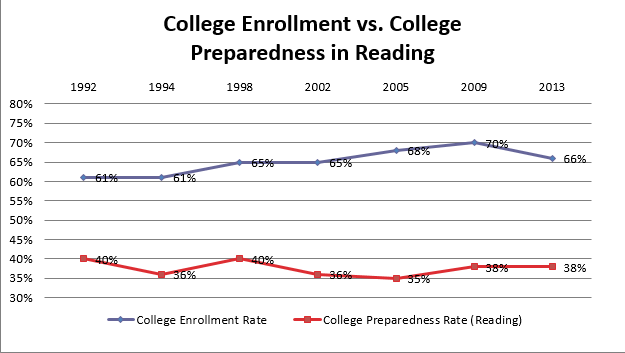

That’s because the proportion of recent high school graduates attending college is far higher than the proportion of twelfth graders who are prepared for college—and that gap has worsened over time. It started at 21 percentage points in 1992, grew to 33 points in 2005, and stood at 28 points as of 2013. (These numbers are for reading.)

(Note: The college enrollment numbers come from Census Bureau table 276 - College Enrollment of Recent High School Completers, defined as: “persons 16 to 24 years old who graduated from high school in the preceding 12 months. Includes persons receiving GEDs.”)

To repeat: The “college preparation gap” is larger now than in 1992 even though the college preparedness rate has remained relatively flat, due to the fact that the proportion of recent high school graduates enrolling in college rose sharply between 1994 and 2009—from 61 percent to 70 percent—before easing back down to 66 percent in 2013.

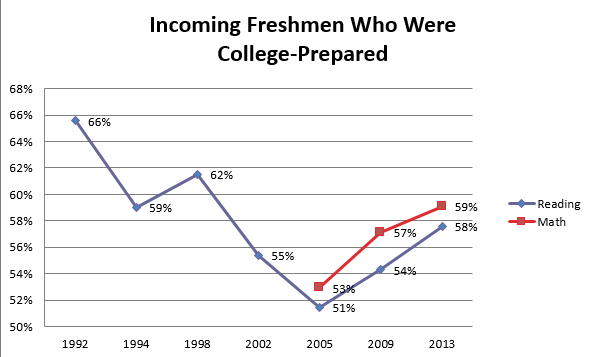

Combine those two trends—college enrollment and college preparedness—and we can make a rough estimate of the number of students who arrived on campus prepared. The next chart takes the proportion of twelfth graders testing at the college-prepared level in reading and divides it by the proportion of that class of students immediately enrolling in college. (To be sure, we have to make a significant assumption that virtually all students who reached the “college-prepared” level on NAEP enrolled in college. That is a stretch, but probably not too much of a stretch to make this exercise useful.)

(Note: For each year, we divided the proportion of students who were college-prepared by the proportion that enrolled in college. For 1992, for example, 40% were college prepared and 61% enrolled in college. 40%/61% = 66%.)

No wonder that, around 2005, the country felt an acute sense of crisis about so many students arriving on campus unready for college-level work. Barely a majority of freshman were “college-prepared,” versus two-thirds of students a dozen years earlier.

But there’s a tiny bit of good news, which is that the preparedness rates of incoming college students are on the rise. That’s partly because of slight improvements in student achievement at the twelfth-grade level, but mostly because of declining college enrollment rates.

***

What to make of all this? To our eyes, these pictures help explain why America’s college matriculation rate is up but its college completion rate is not: We’ve succeeded at motivating more young people to enroll, but we haven’t prepared more of them to succeed at it. All of the higher education reforms in the world—“fixing” remedial education, providing additional supports to students, easing the debt burden, making community colleges “free”—won’t add up to a hill of beans unless our K–12 system gets a lot better at producing young people with the academic skills to succeed once they arrive on campus. (The alternative is to make college easier, which would only diminish the value of completing it.)

Beefing up the effectiveness of the K–12 enterprise is, of course, the aim of ambitious efforts like no-excuses charter schools, the Common Core State Standards, and endeavors to boost teacher effectiveness—all of which deserve support. But it's hard to picture anything on the horizon boosting the college preparedness rate of American twelfth graders above, say, 50 percent any time soon. (Keep in mind that for more than two decades now, it's never been above 40 percent.)

So think about it differently. Another way to make sure that more freshmen are ready for college is to encourage young people who aren’t ready for college to head in different directions. As Charles Murray recently wrote in the Wall Street Journal, “What we need is an educational system that brings children with all combinations of assets and deficits to adulthood having identified things they enjoy doing and having learned how to do them well.” That means taking the “career” half of “college- and career-ready” much more seriously, especially when designing options for high school students.

You may not agree. So what do you make of these data yourself? Let the conversation begin.

Choice and fairness are sometimes cast as values in opposition. This arises from the view that it is unfair to allow some parents to choose their child’s school when others won’t (or can’t). Ultimately, however, choice is the highest form of fairness because it rewards positive behavior and aligns the interests of parents, children, and schools.

This week, I’ll examine the issue from a societal perspective. Next week, I will look at choice from the vantage of the individual family.

Some families can afford private school tuition—often more than $40,000 in New York, and close to that figure in several other major cities. Others move to a suburban district with high property taxes that signify (supposedly) good schools. Some apply to gifted and talented programs. In Brooklyn, we even have a few un-zoned district schools that admit students via lottery. When parents exercise these choices, they are not denounced for acting ‘unfairly.’ The admissions processes of these schools are seldom criticized.

But critics say charter schools that admit kids via lotteries, such as the one my school conducted last week, aren’t fair: We don’t attract enough needy kids, our needy kids aren't needy enough, we don't serve enough special education children, and so on.

As the school’s founder, I spent two years asking parents from across Brooklyn to consider the International Charter School for their kids; I am pleased that many did.

In the week before registration closed, two parents attended our meetings. One mom, who emigrated from Mexico, is unemployed and going through a divorce. Unwilling to send her child to her local elementary school, where just one-quarter of students read at grade level, she applied to seven private schools. Her child was not accepted at any of them. “I’m not poor enough,” she guessed. Luckily, her daughter drew a low number in our lottery and will have the chance to enroll.

Another mom works at a community college and lives in public housing. Her son attends kindergarten at a zoned elementary school in our district. The school’s reputation is improving, yet only 16 percent of the kids currently read at grade level. Her son has a lot of energy; the school says he has ADHD. “But I don't want to medicate him,” she told me. “And I wish his teacher didn't yell at him.” We’ll be able to accept this child, too.

Despite the challenges they and their families face, these parents and 461 others managed to choose ICS. In fact, parents only had to complete a short application that was available on our website twenty-four hours a day; meetings were optional. Parents like these moms invested at least a little time in finding out more and making a choice.

Of course, many others did not. Some might not have agreed with our philosophy and approach. And others, surely, did not get the message—despite fifty meetings in public libraries, bars, hair salons, and community centers. Despite flyers, newspaper ads, Facebook posts, email newsletters, and word of mouth. Despite a city-published school directory and post cards that we mailed to their homes, they did not hear about our free, public school.

Is it unfair that the children of these parents won't have the chance to benefit from our approach? Sure.

To address this challenge, one mom I know proposed that the New York City Department of Education should randomly assign kids to public schools—district and charter—so no one would have to compete for slots. “I want to protect the kids whose parents don’t know they need to act,” she said. That’s a fine and selfless impulse—one that would put paid to the oft-repeated lie that charters cream kids, while addressing the segregation in district schools that is a legacy of real-estate redlining and political gerrymandering.

But is her approach fair? Or fairer?

There’s a human instinct to want to protect people, especially children, from making bad choices. But for choice ultimately to have any value, it must encompass the possibility of making a bad choice—and therefore encouraging us to make good ones.

If large urban districts like New York City had a track record of making excellent educational choices on behalf of their less-advantaged citizens, one might plausibly contend that the government knows best. But as even the most casual reader of education news knows, this is not the case.

Society has a clear interest in producing capable, competent citizens who can perfect our far-too-imperfect democracy. To that end, we collect taxes and mandate that children be educated. Yet evidence increasingly shows that families can’t do worse than bureaucrats in selecting the form and locus of that education.

To students and parents like ours, the inextricable connection of choice and fairness could not be clearer. If parents can move, participate in selective programs, and choose private schools (so long as they first pay their property taxes), then I do not see how we can deny them the right to also choose a charter school. Or not.

Matthew Levey is the executive director of the International Charter School, a Brooklyn elementary school opening this fall. His three children attend New York City public schools.

Atlanta cheating, Eva’s Success Academies, poverty and brain science, and measuring Common Core’s effects.

Amber's Research Minute

Michelle: Hello, this is your host Michelle Lerner of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net. Now please join me in welcoming my co-host, the coach K of ed reform, Robert Pondiscio.

Robert: A Blue Devil at heart.

Michelle: A Blue Devil dad maybe.

Robert: Maybe. My daughter just went to look at Duke last week among other schools and I'm not going to speak for her, but I think she liked it. What's not to like? It's a beautiful school and one great basketball team.

Michelle: Are you a fan of Duke or a hater of Duke?

Robert: You know, I've got to be honest when you grow up as I did in the New York area college sports is just not the thing that it is pretty much everywhere else ...

Michelle: Everywhere else.

Robert: That's not New York. I'm coming to love college sports because of my daughter. No, I only followed the pro game, although Duke could probably beat the New York Knicks easily they're pretty lousy right now.

Michelle: Well my brother is a huge duke fan and he is very happy today but he's also starting a family feud. My husband, a huge Louisville Cardinals fan and yes, my brother text mean things to Daniel every time the Cards lose and Duke wins. Which happened more often this season.

Robert: Last year wasn't it the other way around, Louisville won, or two years ago.

Michelle: Yeah, but when you start a family feud you don't really think about history.

Robert: That's exactly right, gives you something to argue about at Holidays.

Michelle: Yeah because we don't have enough.

Robert: Don't worry you'll make more.

Michelle: On that note let's play Pardon the Gadfly.

Ellen: A group of Atlanta educators were just convicted of RICO violations for their role in the cities cheating scandal. What does this mean for test-based accountability?

Robert: Nothing good. I love accountability as much as the next guy and tests are important. If it weren't for testing some schools, in particular schools that serve low-income, kids of color would just not be getting the attention and the oxygen that they would be otherwise. Did we really want to see it come to this, with elementary teachers convicted of racketeering, facing 20 years?

Michelle: Just like those mobsters.

Robert: Oh, man. Is it just me Michelle or does this just feel like a bridge too far?

Michelle: Well I think there's the whole communications aspect of hauling away teachers in handcuffs is just not a good visual. I mean they did something wrong and they have now been convicted of that I don't think anyone saying they shouldn't have ...

Robert: Absolutely.

Michelle: Been punished. I do you think the fact that we've gotten here is worth considering. Did you read Chad Alderman's piece on Campbell's Law on this topic?

Robert: No I did not.

Michelle: He's basically arguing we can't just say this is Campbell's Law, that if you have any sort of accountability system people are going to find a way to game it.

Robert: Sure.

Michelle: I don't think that's the answer. I think that's the answer if you don't like accountability.

Robert: Yeah, I think that's right and I've talked about it here and elsewhere. I've had my dark night of the soul about accountability. The tests we have, they work, they’re fair, they do what they're supposed to do and they're deeply unpopular. They could even threaten the entire edifice of reform. If you like. On the other hand the methods that are more popular things like portfolio assessment, performance authentic etc. etc. They are so easily game-able that if you're going to have Campbell's law about anything you're going to have it there. I'm no smarter about this than I ever have been. I simply don't know how you square this circle. We don't like test and they lead people to do bad things and the alternative methods are just squishy and insubstantial.

Michelle: I think testing is an imperfect measure but it's the best measure we have and I'm saying this as somebody who's not great on standardized testing, who thinks I can be judged better elsewhere but testing is what we can use. I think it's worth using, I think we should not abandon testing.

Robert: No, no, no and I'm not thinking we should either but it just really gives me pause to see again this idea that we're now seeing criminal convictions prosecutions of racketeer elementary school teachers in handcuffs, facing twenty years of hard time. I just don't think that this is a good thing for reform and a good thing, it's the type of thing that could sap the political will and energy around and ed reform.

Michelle: Unfortunately I think you're right. Ellen, question number two.

Ellen: A New York Times investigation of Eva Moskowitz Success Academies unearthed some polarizing practices. Are you a fan of Eva's approach?

Robert: Wow what a great question. It's complicated; Michelle and I were talking about this earlier. That every good conversation about education sooner or later gets to, it's complicated. Let's just get right to it in the beginning, it's complicated. Yeah, I am and I'm never going to be able to forget the experience that I had teaching in a frankly chaotic South Bronx education school for five years. Once you've had that experience and you see the damage that it does to student learning and engagement you can't not look at what Eva Moskowitz is doing with Success Academy and think okay this is a good thing.

Is she polarizing? You bet you she is polarizing. She doesn't apologize for running her schools this way and lord look at those results. The test scores that they put up there are just jaw on the floor, knock your fillings out spectacular. The other expo exculpatory thing I guess you would say is look at the waiting list. I don't have the data in front of me but I think they have, for every seat there's ten people who want a seat. Whether or not we in education get and appreciation what Eva is doing, parents sure seem to.

Michelle: I think we have to remember that Success Academy exist in a system of choice. I could understand being opposed to some of these methods for your own kid so don't send your kid to Success Academy or if this was every single public school and it didn't matter what parents wanted, this is how your child is going to be educated. I can understand being opposed to that. Guess what if you don't like it you don't have to send your kid there.

Robert: Sure, I think this does; it's another one of those things that speak to the inevitability of choice. On the one hand would I want to see some of the practices at a Success Academy be standardized and used as standard practice? Probably not. Do I think that parents should be denied the right to send their child to one of her schools? Of course not. You know what interesting, I actually just got off the phone with Eva, not more than a few minutes ago because I'm probably going write something about this. What's interesting when you talk to her about this and about the New York Times piece, she was a little irritated, I guess I can fairly say, about what didn't make it into the piece.

Michelle: Of course.

Robert: In other words she ... Look I've been to her school so I think she's right about this. They do dance, they do debate, they do art, they do hands-on science etc. etc. none of that made it to piece, it was all about Eva and the stress she puts on kids and the testing.

Michelle: In reading the piece I was reminded of some of the things that I experience in my K-12 education, which I went to a private prep school. We had to wear uniforms; we had to stand up when adults walked into the room to show our respect. It was a very, very traditional school.

Robert: Look how you turned out.

Michelle: Look how I turned out. It was also an all-white upper middle-class school. I don't think that we should deny this classic, not discipline light education to kids in Harlem. I think there is something positive about a very old-school view of schools and high expectations and I think parents in Harlem, parents everywhere should have the right to opt into this and they have.

Robert: Make no mistake they want it. I've made a joke about this, my father was forever threatening to send me to military school and I wish he had sometimes. I could have use a little bit of that discipline especially when I was 14 or 15 years old.

Michelle: Look how well you turned out.

Robert: Not as well as you Michelle. I think in the end this piece forget success Academy, fan or not a fan about this piece. I think whether you like Eve or not she has become, I think it's fair to say the most polarizing figure in education now. A piece like this that Kate Taylor of the New York Times wrote it's a bit of roar shock test. You tell me what you think about Eva, I will tell you what you think about this piece.

Michelle: You're right on there and the other thing I kept thinking about as I read the piece was in so many industries we value we really hold up hard work. Whether it's the military and how hard they train, whether it's these movies about inner-city schools and how hard the teacher worked. All of these industries we said yes we praise hard work, we praise discipline, we praise all of this stuff and yet there's such a push back.

Robert: This is what it looks like folks.

Michelle: Yup. All right on that note question number three.

Ellen: Nature's Neuroscience journal published a study that tried to link family income and parental education to the surface area of children's brains. Thoughts?

Robert: Wow I'm not a neuroscientist and I don't play one on television. I'm not just a little bit but I'm completely as to how to respond to this. It does remind me of a study that I read a few years ago that I think was in the journal of pediatrics that really talked at great length about toxic stress and how it changed the formation of the brain. It really for me changed the way I thought about educating children from low income communities. Not that this is the pure and exclusive province of low income kids mind you but they're all kinds of stressors that are associated with low income kids and everything from parental neglect to food scarcity etc. If you put small child under enough of these stressors or stress conditions, it can physically change the brain and make it that much more difficult to develop cognitively. I wonder if this is not of a piece with that.

Michelle: Neerav Kingsland blogged about this over on his blog and he's talking about what we should do the taxes, should we redistribute income. I think this falls into everything with education, where if it were just a matter of giving money that would be easy and we could solve it and go home. It's not just a question of money that would be easy, we can just tax more.

Robert: We could just give everybody a high school diploma at birth and then we'll solve the graduation problem.

Michelle: Exactly. I think this speaks to the struggles we have across the ed reform movement of how to talk about social mobility, how to do reform. I think on one hand you have the Eva Moskowitz's out there who are, let's just work really hard and high discipline and all this stuff versus the question of can education really solve poverty?

Robert: There was a terrific piece from your Alma mater George Mason, I believe Tyler Cowen is his name, an economist who wrote a piece in the New York Times the other day, which I would encourage everyone to read, that said it's not the inequity, it's the inequality. That's exactly right it's not inequality it's the mobility that we shouldn't be trying to solve. It sounds like what Neroff is trying to solve is the inequality problem, what we should be trying to solve is the mobility problem.

Michelle: I think that's a really interesting point. What I would like ed reforms to consider more are the cognitive sciences. I think this study could help us with that. I think we sit here and praise Tim Shanahan all the time on the reading and the knowledge. I think ed reformers would be wise to look at the science of brains and science of how kids learn to ensure that our ed reform policies are not speaking in talking points and are actually pushing forward reforms that can work to get more kids out of poverty.

Robert: Now that you said that let me do exactly what you said shouldn't do, which is I'll make a broader over generalization. I think that it's fair to say that we in education tend to be driven more by philosophies than science. Is that a fair thing to say?

Michelle: I think it's fair and on that depressing note that's all the time we have Pardon the Gadfly Show. Thank you Ellen. Up next is everyone's favorite, Amber's research minute.

Michelle: Welcome to the show Amber.

Amber: Thank you Michelle.

Michelle: Did you root for Duke or did you not root for Duke?

Amber: It's terrible because I taught in North Carolina. Our family has a house in the Outer Banks of North Carolina but I was not rooting for Duke and I’m a southerner. I always go for the underdog and I just felt like what's it 1941 since Wisconsin had won and I just thought I want to root for them so I did and my husband was rooting for Duke and it made for interesting yelling at the TV.

Robert: There you go. Wisconsin's a likable team. I will say that.

Michelle: They beat Kentucky so I was happy.

Amber: Yeah that's right. You know Duke is Duke, they're not going to put up a fight every single time.

Michelle: How did you do in the office brackets?

Amber: I did not have much luck. I unfortunately did not fill out the brackets this year; I just missed the deadline somehow. It made it a lot less fun. I'm definitely, next year I'm doing it again.

Michelle: I feel the opposite I was like it's not as fun now that I'm not going to win.

Robert: I was out basically in the round of 64, done, done right away.

Michelle: I don't like how we set it up that you got more points if you picked an underdog. I think Brandon rigged it. I'm just going to out there on the air.

Amber: Who won by the way?

Michelle: Our producer Liz.

Robert: Our Irish national, non-American won the bracket. That shows you how good we are at forecasting basketball here at Fordham.

Michelle: All right what do you have for us today?

Amber: All right the Brownson report came out recently. It's a trio of studies but I'm just going to talk about one. This is the study about Tom Loveless every year; it's called Measuring the Effects of Common Core. Obviously my ears perked on that one. He creates two indices of Common Core implementation by using data from two surveys of state education agencies. One is based on a 2011 survey that reports how many activities, so did the state conduct PD, did they adopt new instructional material, stuff like that. That states have under taken while implementing this CCS and he basically said strong states are those that have pursued at least three of these things to implement the Common Core.

Then he uses another index on the 2013 survey data that asks states when they plan to have implemented Common Core and he basically says strong states are those that indicate full implementation by 2012, 2013, so it's just a little wonky stuff. He analyzes the relationship between the survey data, I just told you about and innate data and he finds that from 2009 to 2013 strong implementer outscored the four states that did not adopt Common Core by little more than a scale point. Again the small, and he says this, he's fair about it, he says that the small comparison group of just four states makes it so the finding are just less reliable because they're just more sensitive to fluctuations.

On the 2013 index there was a difference of 1.518 points between the strong implementers and the non-adopters which is obviously also pretty small. There's that but what's really interesting that I don't think I saw as picked up on in the press is this little, more interesting than a correlation study. Is that he did this sort of dive deep into how teachers reported they were teaching fiction. He found that fourth grade teachers, again with strong implementation states favorite to use a fiction over non-fiction, which is what we would expect. In 2009 and 2011 but when you looked 2013 you saw this huge decline, like 12.4 decline in percentage points.

Robert: That's a lot.

Amber: Teachers were basically moving from more fiction to more non-fiction.

Robert: It's working. It's working.

Amber: This is even better right. Another little interesting factoid that on the bottom line is this non-adoption states, they had a decline too of 9.8 percentage points.

Robert: In the amount of fiction.

Amber: Yeah, from 2009 to 11 which you sit there and think okay so one might take away that Common Core is actually having an instructional impact regardless of whether states officially adopted the Common Core or not.

Robert: That makes sense to me actually. Because I think one of the big messages around Common Core was, news alert kids need more non-fiction and I think that benefited the field at-large.

Amber: Yeah there was a bleed over affect if you will.

Robert: That's also not surprising especially if there's going to be Common Core aligned curriculum and textbooks out there. A fourth-grade textbook will have more informational ...

Amber: People don't want to own that they're adopting Common Core anyway, they're doing it but they're whatever.

Robert: Pay no attention to the standards behind the curtain.

Amber: Yes but anyway I thought at the end one other point that he made just for researchers is going to be exceedingly difficult to figure out a reliable measure on state implementation because the stuff is all so fluid. You've got states that are saying I'm in, I'm out, I'm delayed, I'm paused whatever.

Robert: You know why I'm not sure he's right about that?

Amber: Why?

Robert: You were a teacher, I was a teacher what's the most powerful driver of your instructional decisions?

Amber: Me.

Robert: Really? For those of us who are not superstars, the tests right? I tend to think that as both PARCC and smarter balance gain traction and teachers learn how to teach to those tests I think you'll probably see those affects.

Amber: I think one thing that's the survey data, let's recall who filled out the state education survey data, it's the state education department. Some official, right?

Robert: Yeah.

Amber: One person filling this thing out for the entire state. We know, what does state implementation even mean?

Robert: Give that form to the intern.

Amber: Yeah, anyway I think it's just going be really tough to measure this stuff and it doesn't mean we shouldn't try because we should. I think it was a sensible effort. It's just going to get really, really muddy.

Robert: Tom Loveless to be fair has not been a fan of the Common Core so for him to write this is saying something as well.

Amber: I think and you said something similar Robert another piece of research, folks can look at this and say oh my gosh this is just terrible, this is disappointing or folks can look at it and say hey this is kind of promising it's heading in the right direction.

Michelle: You mean people are going to spin it both sides however they want it. I'm shocked.

Amber: Yeah you're shocked. That's what it is.

Michelle: That's all the time we have for this week's Gadfly Show till next week.

Robert: I'm Robert Pondiscio.

Michelle: I'm Michelle Lerner for the Thomas B. Fordham Institute signing off.

A core assumption of the education-reform movement is that excellent schools can be engines of upward mobility. But what kind of schools? And to what end?

In tandem with the release of several papers, this path-breaking conference will consider thorny questions, including: Is “college for all” the right goal? (And what do we mean by “college”?) Do young people mostly need a strong foundation in academics? What can schools do to develop so-called “non-cognitive” skills? Should technical education be a central part of the reform agenda? How about apprenticeships? What can we learn from the military’s success in working with disadvantaged youth?

Keynote Address: Hugh Price, Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution “What the Military Can Teach Us About How Young People Learn and Grow”

Here’s a fascinating data point: Did you know that the entire weight of Finnish superiority on international reading tests rests on the shoulders of that country’s girls? The reading scores of Finnish boys on PISA tests is not statistically different than those of American boys, or even the average U.S. student of either sex—that’s how wide the gender gap is in Finland. “Finnish superiority in reading only exists in females,” writes Brookings Institution Senior Fellow Tom Loveless in what is surely the most eyebrow-raising finding in the 2015 Brown Center Report on American Education. “If Finland were only a nation of young men,” he observes, “its PISA ranking would be mediocre.”

That girls outscore boys on reading tests is not news. What is surprising is just how profound and persistent are the gaps. Boys lag girls in every country in the world and at every age, and they have for quite some time. But the gender gap on the 2012 PISA in Finland, the global education superstar, is the widest in the world and twice that of the United States. The sober and precise Loveless can barely restrain himself. “Think of all the commentators who cite Finland to promote particular policies, whether the policies address teacher recruitment, amount of homework, curriculum standards, the role of play in children’s learning, school accountability, or high stakes assessments,” he writes. “Have you ever read a warning that even if those policies contribute to Finland’s high PISA scores…the policies also may be having a negative effect on the 50 percent of Finland’s school population that happens to be male?” Now that you mention it, Tom, no. No I haven’t.

That’s not the only shibboleth the report dismantles. Everybody knows that the best way to improve reading scores is to ensure that kids love to read. Except the data say that’s not true. Loveless’s analysis of PISA results shows no correlation between countries that have raised boys’ reading enjoyment from 2000 to 2009 and those that have raised boys’ reading achievement over the same period of time. So what is the cause of the global gender gap? Is it biology? School practices? Cultural influences? Whatever it is, it appears not to be immutable, since the gap has been shrinking on U.S. NAEP tests. At age nine, it’s less than half of what it was forty years ago. “Biology doesn’t change that fast,” Loveless dryly notes.

And a final mystery, perhaps the most confounding of all: Whatever the cause of the global gender gap in reading in school-aged children, it seems to vanish entirely among adults. After the age of thirty-five, men have statistically higher reading scores; by age 55, men remain stronger readers, even though adult women are nearly twice as likely to be avid readers.

SOURCE: Tom Loveless, “2015 Brown Center Report on American Education: How Well Are American Students Learning?: Part I: Girls, Boys, and Reading,” the Brookings Institution (March 2015).

Part II of the latest Brown Center report is called “Measuring Effects of the Common Core.” Loveless creates two indexes of Common Core State Standards implementation by using data from two surveys of state education agencies. The 2011 index is based on a survey from that year, which reports how many activities—such as conducting professional development or adopting new instructional materials—states had undertaken while implementing the CCSS. “Strong” states are those that pursued at least three implementation strategies. The 2013 index uses survey data asking state officials when they plan to complete CCSS implementation. In this case, “strong” indicates full implementation by 2012–2013.

Analyzing the relationship between survey results and fourth-grade NAEP data for reading, Loveless finds little difference between “strong” states and the four states that never adopted Common Core. According to the 2011 index, strong implementers outscored the four states that didn’t adopt the Common Core by a little more than a scale point between 2009 and 13 (yet the small comparison group makes for less reliable findings). Strong states did a bit better relative to the 2013 index, but still outdid non-implementers by less than two NAEP points.

More interesting than these preliminary correlation studies, however, is a finding about how often reading teachers utilize fictional texts in fourth-grade classrooms. In 2013, fourth-grade teachers in strong implementation states who say they use fiction “to a great extent” exceed the portion who say the same about nonfiction by 12 percentage points—yet that is down from 23 percentage points in 2009, mostly due to an increased use of nonfiction. Even non-adoption states showed a decline of 9.8 percentage points during that time. One might take from this that the Common Core standards, with their emphasis on increased nonfiction reading, are having an instructional impact regardless of whether states have officially adopted them or not.

Loveless rightly notes that studying the impact of CCSS at the state level will continue to be challenging as politics, finances, and other concerns alter the status of implementation. As with so many things, one’s interpretation of these results likely depends on one’s view of CCSS, meaning that folks can look at these data and say, “That’s a promising step”—or, “That’s really disappointing.”

SOURCE: Tom Loveless, “2015 Brown Center Report on American Education: How Well Are American Students Learning?: Part II: Measuring Effects of the Common Core,” the Brookings Institution (March 2015).

Brown Center reports on the state of American education are characteristically lucid and informative as well as scrupulously research-based—and they sometimes venture into unfamiliar but rewarding territory. That's certainly the case with the third section of the latest report, which addresses "the intensity with which students apply themselves to learning in school."

Drawing on PISA data (i.e., fifteen year olds), this is an exceptionally timely probe into one of the key temperamental, attitudinal, behavioral, or characterological traits (take your pick of which category it fits best) that may influence both short-term school performance and long-term success. Many people—perhaps taken with the recent attention that's been lavished on student attributes like "grit"—would say, “Of course there's a powerful influence. Why is the matter even worth restating?” But Loveless shows us why, beginning by noting the highly uncertain link between engagement and achievement, at least as both are gauged by PISA, and demonstrating that some countries that best the United States in achievement lag behind us in engagement.

He explains the importance of the "unit of analysis" in all such studies, then goes on to pull PISA's four-part measure of "intrinsic motivation" into its constituent parts and closely examine each of these. And as we accompany him deeper into the issue, it becomes ever clearer that one ought not assume that a higher rating on "intrinsic motivation," at least when applied at the national level, correlates with a country's academic showing.

"Taken together," Loveless writes, “the analyses lead to the conclusion that PISA provides, at best, weak evidence that raising student motivation is associated with achievement gains." Indeed, it may "even produce declines." But the real target of Loveless's findings is the simplistic view that "programs designed to boost student engagement," however worthy they may be for other reasons, can be counted upon to raise achievement. Since they cannot, they do not deserve to be promoted as universal policy nostrums for achievement-hungry lands. Most definitely something to ponder.

SOURCE: Tom Loveless, “2015 Brown Center Report on American Education: How Well Are American Students Learning?: Part III: Student Engagement,” the Brookings Institution (March 2015).