Patty Murray and the return of wishful thinking

No more utopian goals for ESEA. Michael J. Petrilli

No more utopian goals for ESEA. Michael J. Petrilli

Everyone is right to laud the impressive work of Senate HELP Committee Chairman Lamar Alexander and ranking member Patty Murray in producing a strong bipartisan bill to update the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). But it has a significant flaw that needs mending before it becomes law, and it might be up to House Republicans to do the fixing.

The problem, in a nutshell, is that it puts enormous pressure on the states to set utopian goals. That, in turn, will result in most schools being declared failures (and/or create pressure for states to water down their standards), which is exactly what happened under NCLB.

At issue is a true dilemma for policymakers: There seems to be an irresistible urge in education to set aspirational goals. There’s nothing wrong with that, per se—stirring, “shoot for the moon” rhetoric can be motivational and galvanize action. But as Rick Hess and Checker Finn have explained, when it’s time to create accountability systems, policymakers must sober up. If they set unrealistic, unreachable goals, the people working in the system will grow cynical and disillusioned—the opposite of motivated.

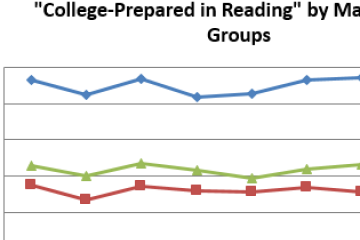

Senator Alexander’s discussion draft bill got this balance right. (So does the House Republicans’ Student Success Act.) It started with the moonshot: State accountability systems will “ensure that all students graduate from high school prepared for postsecondary education or the workforce without the need for remediation.” That’s a fantastic aspiration. But it’s not going to happen, not in the 5–10 years until (let’s hope!) Congress renews the Elementary and Secondary Education act again. I am quite confident about this because, as Checker and I reported last week, the college preparedness rate hasn’t broken the 40 percent mark in at least twenty years. Unless you assume that “workforce preparedness” will require dramatically lower skills in reading and math, it strains credulity to believe that universal “college or career readiness” is attainable anytime soon. We’ll be doing well, over the life of this reauthorization, to get half the high school graduates there. Two-thirds would be a miracle.

But the ambitious, aspirational language of Alexander’s original bill (and the House Republicans’ bill) is OK because it doesn’t require state accountability systems to literally expect all students to reach college or career readiness. Instead, it pivots, simply requiring states to annually measure “academic achievement of all public school students in the State towards meeting the challenging State academic standards in mathematics and reading or language arts, which may include measures of student academic growth to such standards and any other valid and reliable academic indicators related to student achievement.”

Sadly, the compromise bill is not so wise. If I’m reading it right, it requires states to pledge that they will get all of their students to college or career readiness and build those expectations into their accountability systems. Specifically, states must annually establish “State-designed goals for all students and each of the categories of the students in the State that take into account the progress necessary for all students and each of the categories of students to graduate from high school prepared for postsecondary education or the workforce without the need for postsecondary remediation, that include, at a minimum, academic achievement, which may include student growth, on the State assessments,” along with graduation rates.

Now, to be sure, the bill doesn’t establish a federally prescribed timeline like NCLB did (100 percent proficiency by 2014), and it takes great pains to block the secretary of education from micromanaging the “state-designed goals” themselves. If a state wants to, it can decide that its goal is to reach universal college and career readiness by 2050 and design an accountability system that will measure schools’ progress against that leisurely pace. Yet we can all imagine what would happen if states chose that reasonable and realistic path—groups like Education Trust would excoriate them.

These issues will be particularly sensitive when it comes to setting goals for African American and Latino students, as their college preparedness rates are especially distant from the moonshot goals.

So Senator Murray and her allies would drive states into a box canyon. They will face three bad choices. First: acknowledge publicly that not all of their students will be college- or career-ready anytime soon, especially their poor and minority students. Second: aim for universal college or career readiness in the near future and label most of their schools as failures. Or third: redefine “college- or career-ready” to mean “minimal proficiency in reading and math.” This would flush all of the Common Core-related (and other) efforts to raise standards right down the drain.

One would hope that state policymakers would act like grownups and choose option number one. But option two—and especially option three—will be much more politically palatable.

There’s little doubt that the introduction of mandatory state goals reflects a big concession by Chairman Alexander to Senator Murray and her supporters in the civil rights and business communities. It’s not as bad as a federally prescribed timeline would be, and it shouldn’t be a reason for Republican Senators to halt the reauthorization process. As Checker wrote last week, bipartisanship means “everybody holding their noses over provisions they don’t like, even while agreeing that the totality is an improvement over current law.” This bill deserves to be reported out of committee.

Still, it needs to be fixed—either on the Senate floor or in a future conference committee. House Republicans: Get your talking points ready.

A new report by a Harlem-based parent advocacy group calls on New York City charter schools to reduce their long waiting lists by “backfilling,” or admitting new students whenever current ones leave. The report from Democracy Builders estimates that there are 2,500 empty seats in New York City charter schools this year as a result of students leaving and not being replaced the following year.

It’s a deeply divisive issue within the charter sector. When transient students (those most likely to be low-performing) leave charter schools and are not replaced, it potentially makes some charters look good on paper through attrition and simple math: Strugglers leave, high performers stay, and the ratio of proficient students rises, creating an illusion of excellence that is not fully deserved. Charters should not be rewarded, the backfillers argue, merely for culling their rolls of the hardest to teach or taking advantage of natural attrition patterns.

Fair enough, although there’s a distasteful, internecine-warfare quality to all of this: Charters that backfill resent the praise and glory heaped upon those who do not, and seek to cut them down to size. Traditional schools hate them both.

Some disclosure is needed here. When I’m not at Fordham, I’m a senior adviser and teacher at Democracy Prep Public Schools (DPPS) in Harlem, which actively backfills. The leading pro-backfill proponent and primary author of the report is my friend and close colleague, DPPS Founder Seth Andrew. That said, I have serious misgivings about pushing charters to leave no seat unfilled.

Charter operators already have powerful financial incentives to backfill. Empty seats mean fewer dollars. If savvy CMOs decide that they’re better off limiting backfilling, or foregoing it altogether, they must have a pretty good reason. And those reasons abound. Moreover, the entire point of charter schools is operational leeway, the ability to innovate and act in the best interests of the children they serve. The regulatory impulse, however well-intentioned, is anathema to the very idea of chartering.

Consider, too, that Randi Weingarten seems to like the idea. “Charters that get public money should be held to the same requirements and standards as traditional schools,” she tweeted Sunday. If the head of the AFT is trumpeting backfilling, that says something.

Implicit in the backfilling clash is another debate over the role of charter schools in our education system. One vision is of “all-charter districts” like New Orleans, which would take on the obligations of a district, such as serving every child and allowing them to enter at any time. Or you might prefer a more traditional role for charters as alternative schools with greater flexibility and freedom, not necessarily having to be all things to all children. The backfilling debate is something of a proxy fight between these very different visions for charters. Are they a replacement strategy for disappointing schools and districts? Or are they closer to a poor man’s private school? The problem is that charters have been promoted by some as the former while functioning as the latter.

The charter movement has long sold itself as a public schools movement. The sector’s less sober members beat up on traditional schools and districts for “failing our children” and encourage them to emulate charters that are effective with the “same children.” It’s effective, tub-thumping rhetoric, but it elides the myriad ways large and small in which charters are simply not the same as traditional public schools—at least those that deal with the hardest-to-educate students.

Charters—even those that backfill—can exercise much greater control over their student population than most neighborhood schools. They start with parents engaged and motivated enough to enter a lottery. Next come more stringent discipline, higher promotional standards, and refusal to take transient students except at designated entry points. Finally, there’s the “nag factor,” which can wear down students and parents who are not fully onboard with a charter school’s culture or code of conduct. Eventually, those hardest to reach and teach leave of their own accord. They needn’t be “counseled out.”

Let me quickly add that there’s nothing sneaky or nefarious about any of this. I can think of no reason why engaged and motivated students from low-income families should be denied the ability to attend school alongside other engaged and motivated students. Indeed, this is a fair facsimile of what it’s like to attend a district school in a more privileged community. Middle class families—place-bound; not highly mobile—wall themselves off within the educational equivalent of gated communities through attendance zones, selective schools, and district lines. If a child struggles academically or behaviorally, alternative programs and placements (both public and private) are easy to find. Public schools in affluent communities “backfill,” but when mobility is low and the kids who come in are on grade level, it’s simply not a significant issue.

The Democracy Builders report argues leaving seats empty is a “moral issue.” Is it? “Why do the better off get to have stability in their schools, but poor parents aren’t allowed to self-select into such a school?” one prominent charter advocate recently asked me, framing the matter bluntly. If the goal is to get as many low-income kids college-ready as possible—and if limiting backfill creates conditions that increase their number—isn’t that desirable?

Fair-minded people, even those who view schools through a social justice lens, might agree that it is desirable. Many have. But that’s simply not the argument the charter sector has historically made. “We have to be upfront about what we are and what we are not, how we are similar to district schools we compare ourselves to and how we are not—as well as agree that we can never be a replacement strategy as a result of that because we have no solution for naturally high rates of mobility [among] poor kids,” observes my charter advocate friend.

The absence of this kind of candor among CMOs, advocates, and cheerleaders forces charters to play the “we’re better” game with traditional schools and the “our metrics are more valid” game with each other. A more sound approach might be to let authorizers decide whether to encourage backfilling if a local district is starved for quality seats, or greater differentiation in offerings and evaluations when a more robust local charter sector warrants it.

For now, the backfill debate represents the charter movement’s rhetorical chickens coming home to roost. If you say long enough that you’re public schools succeeding with the same kids, sooner or later you’re going to be forced to play by the same rules. If you replicate the conditions of underperforming traditional districts, you should also expect to replicate their results. The push for backfill can only hasten the day when charter schools offer a distinction without a difference; a second flavor of bad. Perhaps it would be better to acknowledge that traditional public schools who complain that they work with the hardest to teach are correct, praise them mightily, and reward them handsomely when they do it well.

“We can be who we in fact are and be upfront about it. We can change what we are to be like traditional district schools,” concludes my charter source. “We cannot be who we are and pretend to be something else.”

The end of federal teacher evaluation mandates, the House overreaches on student privacy, NCTQ’s teacher prep review, and college interruptions. Featuring a guest appearance by NCTQ's Kate Walsh.

Amber's Research Minute

Mike Petrilli: Hello, this is your host Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net.

Now please join me in welcoming my co-host, the Jordan Speith of education reform, Kate Walsh.

Kate Walsh: I'm a little too old for Jordan but I'm happy to be here.

Mike Petrilli: You are a rock star, Kate. You … You are calm under pressure just like Jordan the golfer.

Kate Walsh: You don't know what I am like on the inside but yes I am calm on the outside.

Mike Petrilli: You are. I've seen it. It's very impressive.

Kate Walsh: Yeah.

Mike Petrilli: As we will talk about, just as he was chasing some of the legends in golf you have been chasing the education schools and they are not happy about that. Kate is the president, the executive director, what's your title?

Kate Walsh: President.

Mike Petrilli: The president. That's a great title isn't it? I love it.

Kate Walsh: You're enjoying that title are you?

Mike Petrilli: I am. The president of the National Council on Teacher Quality, which is doing fantastic work on everything related to teacher effectiveness. We're excited to have you with us. Let's get started. Ellen, let's play pardon the gadfly.

Ellen Alpaugh: It looks like federally mandated teacher evaluations are going away. Is that a good thing?

Mike Petrilli: Oh yeah. Woohoo.

Kate Walsh: I probably … I don't know. Maybe we do or don't have the same view of this. We certainly don't think it really matters much. It's a rather insignificant decision. The waivers …

Mike Petrilli: What doesn't? The federal policy doesn't matter?

Kate Walsh: The federal policy on evaluation, while I think it served a certain purpose on the bully pulpit, I think it helped states understand it was important. But the implementation through the waiver system was flawed, shall we say, in that the states wanted to do evaluation well they just went about and did it well. Those that were being forced to do it, because of the waiver, they basically half-assed … Can I say that on the radio?

Mike Petrilli: I'm shocked. Yes you can say that. I'm shocked, Kate, that this would happen. None of us could have foreseen this that when you have a federal mandate that states that don't want to do it well would just go through the motions.

Kate Walsh: It isn't just mandates. You can say … Race to the Top. The states that wanted to do Race to the Top because they bought into the agenda of Race to the Top, they got very serious about it. The states that were chasing the cash, they chased the cash. They got it and I don't think we have a whole lot to show for it.

Mike Petrilli: All right, so let's imagine that … What we're talking about here is again that all the versions of the ESEA bills that are being debated in Congress, if miraculously Congress actually completes its work, gets a bill. All of those bills say we're not doing federally mandated teacher evaluations, that they are going to say this is … What the secretary did through the waivers, these conditions, that would go away. What's your anticipation? We've got now teacher evaluation systems in 40 states or something. Are a big chunk of those going to simply go away?

Kate Walsh: No and they're not. I think that most of those states that have bought into it have them for a reason and they believe in them.

Mike Petrilli: But what about the half-assers? Do those go away?

Kate Walsh: The half-assers won't be any different with or without a federal mandate.

Mike Petrilli: But why don't they just say we never really wanted to do this so let's just not do it and that might be actually better?

Kate Walsh: You're … I don't know. I'm not going to bet with you. Let me put it that way.

Mike Petrilli: All right. Thank you very much, Kate. It sounds like Kate's not too upset about this. All right, Ellen, let's hear question number two.

Ellen Alpaugh: A draft house bill would allow parents to opt their students information out of state data systems. Is this a good idea?

Mike Petrilli: Kate, you think this somehow relates to this other question on teacher evaluations?

Kate Walsh: Actually I think all of this has to do with an overinvestment in the belief that the feds can solve a lot of these problems. This relates to all of the things we're going to address today. I would just argue that the FERPA is a huge concern. Here's an example of how things can go really badly. This isn't about mandating a new policy this is about allowing people to opt out. If that happens education research is going to take a real … It's going to be very dangerous for the future of education research. This is the opposite move as a proactive policy.

Mike Petrilli: Let's explain this a little bit here. We've got this law that's been on the books for, I don't know, 30 years, something like that. FERPA, Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act …

Kate Walsh: It's why I can't see my children's grades when they go to college even though I'm paying the tuition.

Mike Petrilli: Right, that's very interesting.

Kate Walsh: I'm not a FERPA fan.

Mike Petrilli: FERPA is supposed to protect student privacy and it does have some allowances for states to collect data, for example through testing systems, and put together these administrative record systems that many researchers find so useful and make them available to researchers under certain conditions, right? The researchers have to sign away their life in terms of confidentiality or the state has to run the numbers. There's different protocols for making sure those data don't get out of hand.

What the House bill that is being debated now would do would say to parents hey parents, if you want to opt your kid, you want to basically take their records out of that state system, you may do so. That would mean suddenly their data would not be in there when the researcher runs the numbers or when the state tries to figure out the teacher's value-added score or the school's value-added score. It could really wreak havoc on a lot of these policies, right?

Kate Walsh: Yeah and to no good end. I don't know what a parent … What is the parent's interest in saying that Dan Goldhaber, probably the best teacher quality researcher in the country, I don't mean to insult any other friends …

Mike Petrilli: No, he listens to the show. Hi Dan. That is always okay to do a shout out.

Kate Walsh: To deprive Dan Goldhaber of the ability to advance our knowledge in what we know about effective teacher is not a public service. There is nothing the parent gains by not having that test score included.

Mike Petrilli: But in the era of Edward Snowden and all the rest, parents say hey you promised that you're keeping these data safe and that anything that goes out is going to be anonymous, et cetera, but how can we trust you? Do we really think states have their act together enough to know how to protect these data? We really don't think the Chinese could hack it? What if North Korea gets your kid's test score information?

Kate Walsh: Good luck to that. In all the years we've been doing this I don't know of a single instance … I'm sure there has been one but I don't know of a single instance myself in which a parent's privacy or a child's privacy has been violated by our ability to aggregate test scores. It would be nice if those who were fighting for this would be able to cite a little bit of evidence that this has been an actual problem that needs to be solved.

Mike Petrilli: Yup. I understand people on the hill feel like they have to do something with the words "opt out" in it.

Kate Walsh: Yes.

Mike Petrilli: I think we need to come up with other ideas of things that kids could opt out of. They could opt out of free lunch for example. That could be one thing.

Kate Walsh: I think they already have that option.

Mike Petrilli: Darn it. All right, question number three.

Kate Walsh: That's why middle and high schools have very low free lunch rates as opposed to elementary schools.

Mike Petrilli: Mm-hmm (affirmative). All right. Topic number three.

Ellen Alpaugh: Kate, how's it going with the teacher prep review? Are ed schools cooperating with your evaluation of them?

Mike Petrilli: They love you guys. They love you. A little backup, I think most people know this, but NCTQ now has done a couple rounds of this incredible project, ambitious project, to evaluate the teacher prep programs at most of the nation's ed schools. Most recently they not just evaluated them but also rated them.

Kate Walsh: We ranked.

Mike Petrilli: I mean ranked.

Kate Walsh: We changed it from a rating to a ranking.

Mike Petrilli: Ranked them. The ed schools haven't been thrilled about this.

Kate Walsh: No. What we've learned a few hard lessons in there and one of them is that they're not probably ever going to like us too much unless they happen to be in the top 25.

Mike Petrilli: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Kate Walsh: Those that are in the top 25 or 50 are very quick to boast on their websites that they've been highly ranked. But most, let's face it, are far cry from being in the top. But we realized that our primary constituent here are school districts and aspiring teachers.

Mike Petrilli: Yeah.

Kate Walsh: That's who we need to get this data in front of. How the ed schools react to it or don't react to it is not really our primary concern at this point.

Mike Petrilli: Kate, is this an issue around race and class?

Kate Walsh: That comes out of left field.

Mike Petrilli: Yeah, well let me ask. Where it comes out of, there's a big New York Times essay this last weekend, Motoko Rich saying where have all the teachers of color gone and talking about the dearth of teachers of color in the classroom. You could say for these ed schools, or a lot of us would argue, the major thing you need to do is have much higher entrance requirements into ed schools and that would solve many of the problems. Yet if you use test scores for that because of achievement gaps that's going to mean weeding out a lot of potential teachers of color or low incomes.

Kate Walsh: Here I start to get …

Mike Petrilli: I'm curious. Is it the historically black colleges that are particularly frustrated with you? Is it the non-selective colleges that serve lots of working-class kids that are upset with you? Is it the elite schools that are expensive that are doing well in your ratings?

Kate Walsh: That's so funny you ask because it's elite schools that don't do well on our ratings. So if anything we have really angered … Let's use nicer language here. We have really angered the elite schools because they're used to being considered at the top and in fact they're anything but. They lead the problem, shall we say, in their commitment that says they don't have to train teachers they just have to form a professional identity. If you understand what that means you're ahead of me.

But I think this has very little to do with diversity. In fact we have not had any particular push back on that issue per se. From HBCUs, they are no more or no less unhappy with us than anyone else in the ed school world.

Mike Petrilli: All right, very good. That is all the time we've got for pardon the gadly. Now it's time for Amber's research minute. Amber, welcome back to the show.

Amber Northern: Thank you, Mike.

Mike Petrilli: Are you also a big fan of this Jordan Speith character?

Amber Northern: Wow, what a rock star, right? That was amazing. I only watch it when it gets exciting like that and I watched it just to see that kid. It's great.

Mike Petrilli: Some people around here are saying he's a good looking kid.

Amber Northern: He is easy on the eyes.

Mike Petrilli: Robbing the cradle, people. Robbing the cradle.

Kate Walsh: I think he's a lot nicer than Tiger Woods.

Mike Petrilli: Well, did we know that when Tiger Woods was 21? Yeah, exactly. All right, Amber what you got for us?

Amber Northern: We've got a new study in the Journal for the Association for Education Financial Policy that examines the impact of two different types of breaks in college. The kind where you take an internship, and so you just don't take courses but you're taking an internship, and when you take voluntary academic leave. Internships or on-the-job training takes place in a professional job and they work for a semester in a field that they're considering as a career.

Mike Petrilli: Hey, that sounds like student teaching by the way.

Amber Northern: It does.

Mike Petrilli: I wonder did that count?

Amber Northern: It had to.

Mike Petrilli: Yeah.

Amber Northern: Voluntary academic leave is when a student takes a gap semester. This is becoming more and more popular with kids, right.

Kate Walsh: My daughter did a gap.

Amber Northern: Yes, a gap semester or a gap year. They don't withdraw but they choose just not to take courses during that time period. Data are collected from the Higher Ed Research Institute, they collect surveys at the beginning and end of each student's college career. The sample includes about 95,000 students, pretty big sample, 460 institutions for survey years 1994 to 1999. It's a huge sample but it's not necessarily representative because private colleges and religious colleges are a little over-represented in the sample. They tend to participate more than the others.

Kate Walsh: That's not true for the teacher prep review.

Mike Petrilli: That is true also?

Kate Walsh: No it's not.

Amber Northern: 26% have participated in internships, just a little over 2% who took voluntary leave. The control group … This is why this is 30 pages of the study talking about the control group. But they're students who attended the college continuously and full-time but they had to match on 50 different variables. They call it propensity score matching just to make sense of these groups. That's a ton of stuff. But they did the best job they could. They matched on family demographics, student demographics, high school GPA, SAT score, quality of college, whether they are attached to their college, it goes on and on and on.

Key findings. This is the part where you go uh-huh, you nod your head. Overall, results for students who do internships is positive. There is a bump in their senior year GPA, they score higher on the MCAT, which is the medical college entrance exam, they're more likely to want to work full-time, to attend graduate school, to be well off financially, and they report greater increases in their interpersonal skills.

As for those who took academic leave, results are mostly negative. This is what my best friend did in college, I remember it well. Their senior year GPA is negatively impacted, they study less per week upon their return, they are less likely to want a graduate degree, they are more likely to report being overwhelmed during their senior year, it goes on and on. I mean at the risk of oversimplifying, take an internship and don't leave school for an academic leave. Right?

Kate Walsh: Do they know that some of those people were on academic leave weren't asked to take a little leave?

Amber Northern: They specifically took those out.

Kate Walsh: Okay.

Amber Northern: It's all voluntary leave, not probation or anything like that.

Mike Petrilli: Yeah.

Kate Walsh: Because I knew quite a few people who got invited to take a semester off.

Mike Petrilli: Take a semester off. You figure that … No, it's not surprising. That you would think maybe the alternative for academic leave is kids just dropping out entirely.

Amber Northern: Right but they don't. This is … Those kids are all taken out too.

Mike Petrilli: Right. But these are people that come back. Because who knows something's happened in their life, they have a nervous breakdown, they whatever.

Amber Northern: Or in the case of my best friend she wanted to go to Florida, Key West, for a semester with her boyfriend. What are you doing? It was her senior year. Then she came back and she graduated and she found herself. Whatever.

Mike Petrilli: This is consistent, right? That there's other … I feel like some of the other higher ed folks talk about wanting kids to have momentum. Especially low income kids or first generation college goers that when it takes too long to get through college, because they're trying to work and they're only taking a few courses, that they are much less likely to graduate. That you really want them to get to and through and have some momentum going. Taking this kind of time off does not work.

Amber Northern: I think the survey … They asked them a bunch of questions but I think the sense was when these kids came back it was just like they were trying to get through it. There was a lot of less satisfaction among those kids. That they were in it because somebody told them you got to get this four-year degree but they didn't really see the real value in it. There was a qualitative difference too I think in some of the survey data that we saw in the study.

Mike Petrilli: Very good. I always assume that when you go higher ed that it's been a slow news week on the front.

Amber Northern: They gave me a bunch of common core stuff and I'm like I can't do it this week. I just don't want to deal with the common core studies.

Kate Walsh: Mike, you're just not on the bandwagon. I think higher ed's … They're much juicier.

Mike Petrilli: It's interesting.

Kate Walsh: It's a lot of fun to get into higher ed issues.

Mike Petrilli: No, I agree …

Kate Walsh: My favorite journal is Inside Higher Ed, my favorite daily read.

Mike Petrilli: No I'm happy to. Especially the fact that those higher ed institutions should stop taking kids who are not going to succeed there, have no chance in hell in succeeding there. I get interested in that side of the higher ed issues.

Amber Northern: It's becoming under more scrutiny, right? I just feel like you're seeing more rigorous higher ed studies and this whole accountability question in higher ed. Yeah, I think it's really exciting.

Kate Walsh: It hasn't happened yet, Amber.

Amber Northern: You're helping to push that forward.

Mike Petrilli: Very good. Alright, that is all the time we've got. Thanks so much, Kate, for coming and being on the show, and Amber for another stellar research minute. Until next week …

Kate Walsh: I'm Kate Walsh.

Mike Petrilli: I'm Mike Petrilli for Thomas B. Fordham Institute signing off.

The debate over annual testing has taken center stage as Congress considers reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Assessments provide critical information for parents and legislators on student progress, but when does annual testing become overtesting? And will it survive reauthorization? Watch Fordham's Mike Petrilli and AEI's Mike McShane discuss testing and accountability in the wake of the Senate hearing on the new ESEA.

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation, best known for its scholarship programs for low-income gifted students in high school and college, has entered into the policy realm by beating the drum on an important issue—closing the excellence gap. Gifted-education expert Jonathan Plucker and his coauthors grade states on how they educate an oft-forgotten class of learners: high-performing, low-income students. (We at Fordham often refer to high-achieving students as high flyers.)

The report assesses states on inputs, which include requiring the identification of gifted students, providing services for them, and establishing pro-acceleration policies. Predictably, but still dishearteningly, not one state earned an A for providing needed support for their low-income high-flyers. On average, states only implement three of nine desirable policies, and no state implements more than six. Only two states require gifted education coursework in teacher or administrator training. The best grade, a B-, went to Minnesota, in part because it requires gifted students to be identified and given services.

Helpfully, the report also grades states on outputs. It reports the number of their students who reached “Advanced” on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) assessments or scored a three or higher on Advanced Placement exams (not necessarily the best proxies for measuring outcomes for high flyers). Massachusetts leads the pack, with 18 percent of students scoring Advanced on eighth-grade math assessments—but only 6 percent of those qualified for free or reduced-price lunch. This excellence gap needs fixing, and the authors warn that “without more deliberate focus on this issue, our education system will become an unwitting accomplice to the nation’s growing income inequality.”

The report recommends that states make high-performing students highly visible, remove barriers that prevent students from having access to academically challenging coursework, and hold state departments of education accountable for the performance of high flyers.

We ought to ponder why we have no problem ensuring that gifted, low-income athletes get athletic opportunities, but seldom grant their Mathlete counterparts the same opportunities. These straightforward, commonsense recommendations might alleviate that shortcoming.

The Jack Kent Cooke Foundation plans to update this report periodically; let’s hope states live up to their potential and support their high flyers.

SOURCE: Jonathan Plucker et al., “Equal Talents, Unequal Opportunities: A Report Card on State Support for Academically Talented Low-Income Students,” Jack Kent Cooke Foundation (March 2015).

Back in January, the Education Research Alliance (ERA) for New Orleans released a study looking at patterns of parental choice in the highly competitive education marketplace. That report showed that non-academic considerations (bus transportation, sports, afterschool care) are often bigger factors than academic quality when parents choose schools. It also suggested strongly that it was possible for other players in the system (e.g., city officials, charter authorizers, the SEA) to assert the primacy of academic quality by a number of means (e.g., type and style of information available to parents, a central application system). A new report from ERA-New Orleans follows up by examining school-level responses to competition, using interview and survey data from thirty schools of all types across the city.

Nearly all of the surveyed school leaders reported having at least one competitor for students, and most schools reported more than one response to that competition. The most commonly reported response, cited by twenty-five out of thirty schools, was marketing existing school offerings more aggressively. Less common responses to competition included improving academic instruction and making operational changes like budget cuts so that the need to compete for more students (and money) would be less pressing.

These latter two adaptations are typically the ones that market-based education reformers expect to occur in the face of competition, yet just one-third of surveyed leaders said they responded in these ways. That low level of response in this hypercompetitive market should be worrying. While advertising is an obvious first response to competition in any competitive sphere, it won’t make academically weak schools stronger; neither, when everyone is shouting at the same volume, does it make academically strong schools stand out for parents. And we must assume that both strong and weak schools are in that default reaction category.

There are, however, two other important takeaways that may show signs of hope for competition-driven quality: First, the school leaders were more apt to respond to competition strategically when facing more intense competition (either from the number or higher quality of competitors). Second, a central school application system has the potential to be a game-changing tool by making schools more easily comparable along quality lines. In New Orleans, the OneApp system was only in its first year of operation during the period under study here, and the authors suggest that the common information source and application system could be used by outside players (especially charter school authorizers) to ratchet up the competition to a high enough level that schools have incentives to focus on academic improvement, not just marketing themselves to stand out.

Nevertheless, authorizers should take note. If parental choice is not likely to be an effective quality control mechanism, then aggressive oversight is essential.

SOURCE: Huriya Jabbar, “How Do School Leaders Respond to Competition? Evidence From New Orleans,” Education Research Alliance for New Orleans (March 2015).

As part of its College Match Program, MDRC has released an application guide for “counselors, teachers, and advisers who work with high school students from low-income families and students who are the first in their families to pursue a college education.”

A “match” school embodies two important qualities: It is academically suited for the student, and it meets her financial, social, and personal needs. Unfortunately, “undermatching”—enrolling in schools for which one is academically overqualified or not applying to college at all—is all too common for low-income kids, driving down their college completion rates. Myriad factors at the student, secondary, and post-secondary levels can lead to this phenomenon, including lack of information, concerns about leaving home, minimal training for adults working with students, and limited college recruitment practices.

MDRC’s solution is the College Match Program. Between 2010 and 2014, it placed “near-peer” advisers, who are recent college graduates with training in college advising, in low-income high schools (eight in Chicago and two in New York City) to support students as they navigated the school-selection and financial aid application process. Approximately 1,200 students were served. Researchers conclude that students are willing to apply to selective colleges when they (1) have an opportunity to learn about the options available to them; (2) engage in the college application process early enough to meet important deadlines; and (3) have support and encouragement along the way.

As a former high school teacher who often felt ill-prepared to offer advice to college-bound students, I wish I had had access to MDRC’s guide. It’s informative, well-organized, and easy to use. It carefully describes the six-stage process, providing timelines, online resources, and real-life case studies for each step. It also offers tips that describe various keys to success, such as building a “match culture” within a school, enlisting teachers and other staff to assist in integral stages, and engaging parents, who are typically as unfamiliar with the process as their children.

The authors caution readers not to treat this document as a “user’s manual for creating and implementing a match program.” All the same, it provides valuable insight and resources for those hoping to better guide an underserved population through the college application process.

SOURCE: D. Crystal Byndloss et al., “In Search of a Match: A Guide for Helping Students Make Informed College Choices,” MDRC (April 2015).