Pre-K and charter schools: Where state policies create barriers to collaboration

Charter schools get the short end of the stick. Again. Michael J. Petrilli and Amber M. Northern, Ph.D.

Charter schools get the short end of the stick. Again. Michael J. Petrilli and Amber M. Northern, Ph.D.

You don’t have to be a diehard liberal to believe that it’s nuts to wait until kids—especially poor kids—are five years old to start their formal education. We know that many children arrive in kindergarten with major gaps in knowledge, vocabulary, and social skills. We know that first-rate preschools can make a big difference on the readiness front. And we know from the work of Richard Wenning and others that even those K–12 schools that are helping poor kids make significant progress aren’t fully catching them up to their more affluent peers. Six hours a day spread over thirteen years isn’t enough. Indeed, as our colleague Chester Finn calculated years ago, that amount of schooling adds up to just 9 percent of a person’s life on this planet by the age of eighteen. We need to start earlier and go faster.

But the challenge in pre-K, as in K–12 education, is one of quality at scale. As much as preschool education makes sense—as much as it should help kids get off to an even start, if not a “head start”—the actual experience has been consistently disappointing. Quality is uneven. Money is spread thin. Teachers are poorly educated. And benefits quickly fade. There are exceptions, of course, but it’s no easier to run a great high-poverty preschool than to run a great high-poverty elementary school. It’s possible, but rare.

So if policymakers want to ramp up high-quality preschool programs, where should they turn? To the big and often dysfunctional urban school districts that struggle so mightily to get the job done for K–12 students? To Head Start centers, which continue to resist a focus on academic preparation and hire mostly low-wage, poorly trained instructors? To for-profit preschool providers? (We don’t hear many liberals proposing that.)

What the Left and Right can get behind are pre-K programs that deliver the goods: nonprofit institutions that prepare young children, and especially low-income children, for the rigors of education today. What could be a more ideal solution, both politically and substantively, than high-quality charter schools? Why on earth, then, is it so difficult for America’s high-impact, “no-excuses” charter schools—committed as they are to helping poor kids succeed in K–12 education and proceed to good colleges and worthwhile careers—to participate in pre-K programs? Who wouldn’t want the KIPPs or Achievement Firsts or Uncommon Schools of the world to be able to get started with three-year olds and work their edu-charm as early as possible?

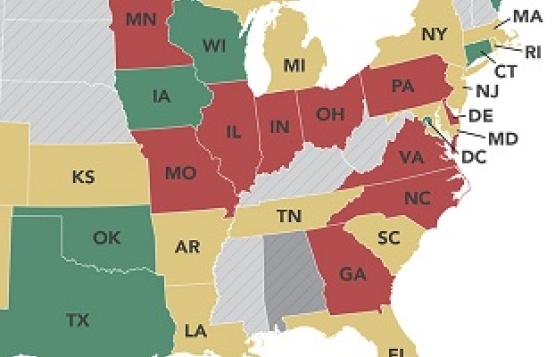

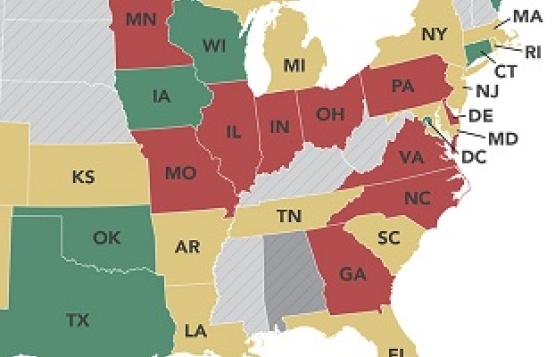

Commonsensical though it may be, however, the preschool and charter school movements have grown up parallel to one another, rarely intersecting as often or effectively as they could. Because of the siloed nature of policymaking and finance, charter schools in many states are greatly restricted (and in some places even prohibited) from offering preschool. That’s what we found in our new, pathbreaking study, Pre-K and Charter Schools: Where State Policies Create Barriers to Collaboration.

To conduct the analysis, we approached early childhood and charter school expert Sara Mead at Bellwether Education Partners. Sara is an education policy veteran, having once directed the New America Foundation’s Early Education Initiative and spent time at Education Sector and the Progressive Policy Institute. She now serves on the District of Columbia Public Charter School Board. Sara’s colleague Ashley LiBetti Mitchel, a savvy public policy analyst in her own right, co-designed and co-authored the study. (The research was made possible through the generous support of the Joyce Foundation, the Walton Family Foundation, the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools, and our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation.)

Among Mead and Mitchel’s most dismaying findings: Charter schools cannot offer state-funded pre-K in the thirteen states that lack either charter laws or state pre-K programs. In nine other cases, state law is interpreted as prohibiting charters from offering pre-K. Where the practice is permitted, charters still face all sorts of barriers, including meager pre-K funding (and/or district monopoly of funds), woefully small programs, and restrictions on new providers. Charter schools are often barred from automatically enrolling pre-K students into their kindergarten programs without first subjecting them to a lottery.

In other words, charter schools get the short end of the stick. Again.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. As this report proposes, we can do much to demolish the barriers that prevent the charter and pre-K sectors from working together. But that requires us to understand how two programs with very different origins can be brought together. New York Times columnist David Brooks gets it. Last November, he posited that “a collaborative president might jam a mostly Democratic idea, federally financed preschool, and a mostly Republican idea, charter schools, into one proposal.” This horse trade—more support for charter schools in exchange for more support for preschool— might represent a bipartisan way forward. Why not charter preschools? Why not charter elementary schools that start at age three?

Policymakers, this is low-hanging fruit. Why not pick it?

Shortly before ten o’clock on a recent warm summer morning, the grand old Apollo Theater on Harlem's 125th Street filled up with the friends and families of the members of Democracy Prep Charter High School's third-ever graduating class. The soon-to-be graduates milled about in the lobby, hugging each other and taking selfies in their bright golden robes and mortarboards before filing in, grinning, for their moment of glory.

I got to know each of these sixty-one students in my senior seminar class this year. It was a deeply satisfying year for the school and an extraordinary one for the students, each of Latino and African descent, and nearly all of modest means. Come September, every single one of them will attending colleges, including several institutions that would be the envy of parents and students at the elite private schools just a few blocks south of here. Ashlynn and Chris will be heading to Dartmouth; Hawa turned down Stanford to attend Yale; Tyisha will join the freshman class at Princeton. Other members of Democracy Prep's Class of 2019 are bound for Emory, Smith, SUNY Albany, Boston College, and Brown, among many others.

Class of 2019 is not a typo. It has become nearly de rigueur for high-performing, "no-excuses" charter schools to add four years to the graduation date for each departing class. It marks the year departing scholars are scheduled to graduate from college, an endearing aspirational quirk and one last dose of high expectations before commencement. But there's an uncomfortable truth that must be acknowledged even as we celebrate. At present, the odds are still against most low-income kids of color reappearing at another graduation ceremony four years hence. Or ever.

A sobering recent report from the National Center for Education Statistics shows just how long the odds are, even for those with college aspirations. Starting in 2002, researchers began tracking fifteen thousand U.S. high school sophomores from across the socioeconomic spectrum. At that time, roughly 70 percent of those tenth graders planned to go to college. That ranged from a high of 87 percent among students whose parents had the highest level of income and education to 58 percent of those whose parents were the least educated, poorest, and largely unskilled. Among this latter group of students, a mere 14 percent of the total—and only one in four of those who planned to as sophomores—had earned a college degree by 2014.

Many of us have aspirations that exceed our abilities. Thus, the most obvious explanation for this disparity would be that low-income children were unprepared or overconfident, or else lacked what it takes to succeed in college. But the study showed otherwise. Writing in the New York Times, Susan Dynarski, a professor of education, public policy, and economics at the University of Michigan, notes that each student in the study took math and reading tests. Nearly three out of four of the highest-scoring students from the most affluent families completed a college degree as of 2014. But for low-income kids with the same achievement level, the college completion rate was only 41 percent. Even more telling: "A poor teenager with top scores and a rich teenager with mediocre scores are equally likely to graduate with a bachelor's degree. In both groups, 41 percent receive a degree by their late twenties," Dynarski observed. The American Enterprise Institute’s Andrew P. Kelly made a similar point in a paper last year for Fordham’s “Education for Upward Mobility” conference.

The report adds cold, hard data to what has long been known among education reformers and the high-achieving charter schools they champion: Getting low-income "first-generation" kids into college is hard. Getting them to graduate from college is harder.

For years, pioneering charter school networks like KIPP, YES Prep, and others won legions of admirers by ensuring that nearly every student they graduated went to college, usually the first in their families to do so. A 2011 report from KIPP itself, however, found that only 33 percent of their earliest cohorts of students had actually earned a college degree. On the one hand, that's roughly four times higher than the rate for disadvantaged students as a whole. But it was far below KIPP's own internal goals and a wake-up call for a reform movement that had long campaigned for college as an essential path to upward mobility.

Since then, KIPP and others have become increasingly focused on "college match." This typically means partnering with colleges like Franklin & Marshall and Spellman College—which tend to feature high graduation rates both overall and for low-income students, generous financial aid, and diverse social environments—to make it more likely for "first-generation" kids to persist and succeed.

Perhaps even more critically, we are learning that maintaining close ties to alumni matters a lot. "Once in college, students submit course selections, financial aid documents, and most importantly, college transcripts to us so that we can academically advise and proactively address any issues that may come up," says Jane Martínez Dowling, executive director of KIPP NYC Through College. For middle-class and affluent children, this kind of constant monitoring, advising, and problem-solving tends to be baked into their lives, whether through aggressive helicopter parenting or simply having friends and family members who've been to college and are neither awed by the process nor intimidated by pitfalls. My now-former students will benefit from this kind of post-graduation counseling—Democracy Prep, like KIPP and many others, keeps close tabs on alumni. So far, nearly nine out of ten remain enrolled—an encouraging figure, albeit from a cohort of fewer than 100 students.

The senior speaker that day, Fordham-bound Briana Mitchell, took justifiable pride in the accomplishment of her classmates, who have already beaten the odds simply by graduating and winning acceptance to college. “Who would have thought that these students are going to some of the top colleges and universities around the world?" she said, to enthusiastic shouts and applause. "Who would have thought that this could happen when all odds were against us?"

Graduation day is a time for celebration and excitement, not for doubts. But there can be no doubt that the hard work is not over for these kids. In many ways, it's just begun.

Editor’s note: This post originally appeared in a slightly different form at U.S. News & World Report.

The ESEA opt-out amendments, low-income college-goers, Nevada’s education savings accounts, and teacher pensions.

Amber's Research Minute

Mike: Hello, this is your host Mike Petrilli at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute here at The Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net and now, please join me in welcoming my co-host, the Pluto of education reform, Robert Pondiscio!

Robert: That means I'm no longer a planet?

Mike: You're no longer a dwarf planet. You're bigger and icier than we thought.

Robert: Nice save.

Mike: How about that. Hey, it's Pluto week. This has been fun. Have you been following along at all, Robert?

Robert: The only thing I heard was interesting. The guy who discovered Pluto's ashes were put on a satellite like some twenty, twenty-five years ago. Not a satellite, a spacecraft, and they are this week making their closest approach to Pluto.

Mike: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Robert: Discovered and named Pluto these ashes, little bits of it are out there right now.

Mike: Oh they're on the satellite? Oh, that's very interesting. I've been thinking about how the technology out there is 2006 era technology because this thing has taken that long to get out the ... what is it? Nine billion miles or some crazy-long trip to get out there.

As a result ,it may not be as high-tech as we wish because, for example, it can't take all the pictures and the data and transmit it at the same time. I wonder, we probably have more computing power on our iPhones at this point than it has.

Robert: On Apollo 11.

Mike: Because of 2006, right? Guess what, it's kind of like the No Child Left Behind Act, it's still out there in orbit. Flying around.

Robert: A little bit about broadcast, this is fascinating. Broadcast, terrestrial broadcasts, then never go away. They just continue leaving the Earth at the speed of light forever which means I think, right around now, old I Love Lucy shows are just reaching Alpha Centauri.

Mike: Yeah, very cool.

Robert: What other civilization is going to see that?

Mike: We've all seen this is the sci-fi movies. We know. They start worrying about us. They see the clips of the Hitler clips and stuff and they start saying, "We got to go save those people!"

Robert: No intelligent life there. Not worth saving.

Mike: Well I think when the Donald Trump tapes reach them they'll certainly still believe that.

Robert: I believe we'll be in the home ... or worse by the time that happens. By the the time it gets there.

Mike: Okay, we've got a lot to cover. It is the middle of the summer, but man things are hot in education reform. Let's play Pardon the Gadfly. Clara, get us started.

Clara: Last week The House passed the ESEA amendment that would allow students to opt out of state tests without penalizing schools. Thoughts?

Mike: Robert, I understand that Mike Lee in the senate has a similar amendment, maybe it goes even further. Look, this is a very tricky issue.

Robert: Is it ever.

Mike: What this is about is saying that, if a parent decides to opt their kids out, that basically the school and the district and the state should be held harmless. The issue is that right now, all those entities are supposed to have at least ninety-five percent of their kids tested. The reason is because if you don't have that rule in place, then you would create a perverse incentive for schools to tell Johnny to stay home on test day if they don't think Johnny's going to pass the test.

This is now clashing with this desire to give parents this right to opt out if they don't see the value in their kids taking this test. If these amendments go through and become law, this could wreak havoc for all sorts of things, Robert, because if you have lots and lots of kids opting out, suddenly the test score data isn't worth much. You can't use it for accountability, you can't even use it for research. A lot of researchers freaked out. On the other hand, do we really want to be fighting parents over this?

Robert: Well this is so complicated, right? I keep saying on this podcast I've got a complicated relationship with assessment and you just crystallized it perfectly. On the one hand, if you're all for parental choice and prerogative you can say, "Well, no except in testing those you have t.,"

We have to respect parental choice, I would argue. We have allowed the assessment tail to wag the educational dog and this is the price we're paying. We have to ... and I'm not going to sit here say I know what the answer is, but we have to get right on testing.

Mike: That's fair. Look, the J. Green's of the world out there blame Common Core. I tend to blame teacher evaluations as the straw that broke the camel's back. These test based evaluations done, not quite very thoughtfully, in many places. Then there's also just the transition issue. These tests don't count right now, which I think is the right call.

The tests don't count for kids. They don't count for schools as we're transitioning, but that makes it a lot harder to say, "Therefore kids you got to sit down and take the test anyway," especially high school kids who are taking oodles of AP tests and SATs and ACTs and everything else at the same time. A couple of years from now we get through this transition, they start to count in some positive way for kids.

They say, "Look, you get a good score on your Smarter Balance, you don't have to take the ACT you can use that score to get into your state university." Some of these problems maybe go away. In the meantime we've got to muddle through.

Robert: Well, it's be nice if we could do more than muddle. Ti would be nice if we can figure out what the correct relationship is with testing in our schools but I think you hit the nail on the head. It really comes down to the accountability measures.

It just defies credulity to say, "You're going to make teachers accountable, individual kids test results and then be surprised that that testing dominates the educational experience. Some of the Gordian knot has to be done. I'm not going to sit there and say I know how to do it, but that has to be uncoupled somehow.

Mike: All right. Topic number two ... Oh, by the way, Robert, hypothetically if you were still teaching and it was not summer, do you think you would be having you kids follow along with this whole Pluto thing and debating, is it a planet, is it a dwarf planet? Who gets to decide these things?

Robert: That's a great question. What I teach right now is Civics so I think I would be more ... it's been a great summer for Civics since so many things have ...

Mike: Should we have funding fro NASA? There's a Civics question.

Robert: If I had my class now these are great topics to debate.

Mike: All right. Topic number two Clara.

Clara: A recent study from the National Center for Education Statistics reveals just how difficult it is to get low-income kids to and through college. Why aren't more high-achieving low-income kids graduating from college, and what can be done to fix the sobering trend?

Mike: You heard about this this week, Robert. Talking about some of the young people that you have been teaching at Democracy Prep and the tough road ahead from them. The numbers are what, nine percent according to some measures of low-income kids get to and through four-year degrees. Others put it at fourteen percent, either way we're talking about very small numbers.

Robert: Yeah, and I've written about this for a couple of years in a couple of different places because, look I'm charter guy, I'm all about charters and choice and whatnot and I left a very nice career to work with low-income kids of color in the South Bronx and elsewhere so this is the important topic personally. The feel-good narrative around charter schools for years has been, had not always been for all the right reasons. First generation kids going to college a hundred percent of the graduating class going to college.

There has been less attention historically to what happens once kids after they get to college. Here we're seeing some really encouraging developments but the numbers are still kind of depressing. The big study that everybody remembers within five years ago was Kip and God bless them, they didn't have to do this, but Kip monitored their own student performance and found, if I'm remembering right, thirty-three percent of kids who had passed through Kip Wright Middle School ended up graduating college within six years. Now you can look at that and say ...

Mike: It's gone up since then. I think they're getting close to fifty percent at this point?

Robert: I have not ... I've asked, frankly, Kip, I want those numbers. Send them to me," I've asked a couple of times and you keep hearing, "Well, they're getting better," but I want the data. If the data is really heading in the right direction. The sobering thing that came out in was in the NCES study that showed, and it was longitudinal.

They started tracking kids in 2002 and at that point, something like eight out of ten kids rich or black, white, et cetera said as high school sophomores, "Yes, I want to go to college." That's where the divide happened. Even high-achieving low-income kids. This was the big news. High achieving, low-income kids were just as likely to graduate from college forty-one percent of them as low-achieving high income.

Mike: Yes, or middling achieving.

Robert: Mediocre for lack of a better description. That shows that it's not about preparation or it's not just about preparation. That something else is going on. We're a lot better than we sued to be at getting low-income kids to college, we got a long way to go at getting them through college.

Mike: Right, and this is an important point. I've certainly made the case that we still have a huge problem with college preparation. That if you look at the numbers, we're still at about thirty-five or forty percent of kids with the reading and math skills to enter college, college-ready. Guess how many kids these days are graduating from college? About thirty-five or forty percent. Now, those are not the exact same kids, as you say, the low-income kids are under-represented in terms of graduation, even those kids that are well-prepared. Some of these rich kids are over-represented; that they get through even thought they don't have the reading and math skills.

There is something else that's going on. I've looked at other numbers that basically show if you look out into the early 20's almost every high school graduate at this point is taking a shot at college. It is we basically have universal college educational at this point in terms of trying it. Universal access. The problem is they're not completing. They're not getting those degrees, preparation's a big point, but it's not just preparation even these kids at least have the reading and math skills. Maybe they're under-prepared in other ways but they've got the reading and math skills, but they're still not making it through and that's when you start looking at the costs of college.

Robert: I think some of the most interesting work has been done by Kip and other so-called high-achieving and no-excuses charter schools where they really focus on getting kids into not just the best possible match but the right possible match. It turns out, and I'm going to paint with a broad brush here, small private colleges seem to have a much higher graduation rate with low-income first generation college-goers. There's been a big research public research universities. They're now funneling more kids to say the Franklin and Marshall as opposed to Boise State.

You know Boise State, they may do a great job, but it does look like where kids go to school and the supports that are there for them matter a lot. The degree to which some smaller, more inclusive schools are able to keep skids attached and persisting. If you think about this, if you are a affluent kid and whose parents went to college, you have a lot of this stuff baked into your life. Your struggles and then your parents said, "O, go talk to the Bursar, go talk to this professor." The process is de-mystified for you. This sounds counter-intuitive but even small problems like a bus to get home can be disabling for someone who is a little bit of a fish out of water.

Mike: All right topic number three. I think the topic is Pluto a dwarf planet or a real planet? No, just kidding. What's topic number three, Clara?

Clara: In a recently penned blog post Howard Fuller calls Nevada's education Savings Account Program "A gift to the opponents of the parent-choice movement." What does he mean by this and do you share the same concerns?

Mike: Howard has been making this case, and he has the right to make it. He's got the Civil Rights credentials absolutely going way back to say, "Hey, I support school choice because I see it as a way for poor kids to get opportunities they don't have that rich kids today have plenty of," and that's why he supports school choice programs that are targeted at low-income kids and he looks at the Nevada program and look, I wrote about this too. I said that, "This Nevada ESA thing does not does appear to be designed for low-income kids."

It is not likely to be ... there's not enough money, not enough accountability. If you want to help low-income kids in Nevada, you're much better off looking at what Nevada is doing around charter schools, high-quality charter schools. Now, I still support the ESA thing because I think it's an interesting experiment and you're going to get some innovation out of it and find some new models that we may not have seen before, but Howard says, "Look, you support school choice because it's a way to help poor kids. If it's not about helping poor kids, he's not for it.

Robert: Am I allowed to disagree with Howard Fuller?

Mike: You absolutely are.

Robert: Howard Fuller. And I’m a punk.

Mike: A dwarf planet. Robert, is the way we put it, yes.

Robert: I say I've got a complicated relationship with testing. I have an uncomplicated relationship with choice, I'm for it. Hearing it at full stop. I got to choose my kid's school. I want you to be able to choose your kid's school. Where I guess I would push Mr. Fuller on this ... because I'm earnestly curious about this; does he not see or agree with the idea that choice might create the conditions that will create more high-quality options for the kids he cares about?

I suspect that he's looking at the existing universe of choices in Nevada and elsewhere and saying, "Okay, all of you are enabling a habit right now is to get the educational…well, so to speak, into those schools. My kids are going to be left outside. Is it not true, Dr. Fuller, that this kind of program creates the incentive to expand the pie. To create more high-quality options?

Mike: Well, it could. You could design it that way, but I think in this case the details matter. It's five thousand bucks, right? Which even in low-spending Nevada is not enough most likely to provide a high-quality education.

Robert: Nevada. New York City, where I live, is three or four hundred.

Mike: Well that may be tuition but that's not what it costs. That's why they're going out of business. The point here is, if you want to make this work in Nevada what's likely to happen is that middle income or high income parents are going to top off that five K, right? They're going to go to a school, now maybe the Catholic school they've only got to pay an extra thousand dollars a year, and even low-income parents in most cases can, we have seen in other programs can figure out a way to scrape that together, but a lot of the other options are going to be ten thousand dollars a year, right?

So in that case, he's right. This is a program that's mostly going to benefit, going to subsidize the education of better-off kids. At least if it's being used fro traditional, private education. If you're Howard Fuller, you say, "Look, I sure I simply," maybe he'd be willing to support universal voucher if it was going to be funded high enough so that the poor kids actually had a shot at getting into high-quality private schools.

Robert: If you're an educational entrepreneur right now, don't you want to set up shop in Nevada?

Mike: Yeah, but I'm not going to serve poor kids.

Robert: Why not?

Mike: It's not enough money to serve them well.

Robert: You can serve a lot of them.

Mike: How?

Robert: Nevada's a fairly low-income state.

Mike: I know, but it's still, you're looking at five K. This is the argument that Mike Goldstein made in our Wonkathon was that it's just not enough money or maybe was it Goldstein or was it Neerav but that ... maybe it was Neerav There's just not enough money there to make a difference. We've seen that with those charter schools. You look at a place like Ohio, you look at some of the other low-performing charter states. One problem is accountability. The other problem is low funding. It's just really hard to run a great charter school at seven K a year. It's going to be the same thing with the essays.

Robert: Are you saying that funding matters?

Mike: I am saying that funding matters. Absolutely.

Robert: Who are you? What have you done with Mike?

Mike: I am a full-sized planet. Thank you. I am the Saturn of the education policy today, Robert. All right, that;'s all the time we've got for Pardon the Gadfly. Now it's time for everyone's favorite. Amber's Research Minute. Welcome back, Amber.

Amber: Thank you, Mike.

Mike: We've been chatting about Pluto. Two questions. One) Have you been following along? Number two) is it a planet or a dwarf planet in your opinion?

Amber: I haven't been following along, but my husband has. I believe he says it's a planet.

Mike: It's a planet!

Robert: It's planet again.

Amber: Yes.

Mike: No, no, no. It's still officially a dwarf planet, but this mission may help it get bumped back up to planet status because they are finding it's bigger than they thought before.

Robert: Wait can you call it a planet? Is it not just a little planet?

Mike: That was a good one.

Amber: Somebody's going to get upset by that. I have a feeling.

Mike: That's very true.

Amber: When you watch it on TLC it's Little People. It's not dwarfs.

Mike: It's not dwarfs. Exactly. Oh, so now you're comparing those people to little planets, huh?

Amber: I'm not following planets, but I'm following TLC little people. What does that say about me.

Mike: Amber ... well, it says we'd better shift into education research. Okay, what you got for us this week?

Amber: About a report about whether education partner that examines changes to teacher pensions. Sorry, got to do a teacher pension study. They look at the last thirty years and how these things have changed. The report title, this is great, "Eating Their Young," That's a ... I don't even know if Fordham would do that title.

Mike: We might, but we would put a dinosaur on the cover eating its young.

Amber: Yeah. Historical data set, they use it basically had eighty-seven retirement systems from all fifty states. They look at the data from 1982 to 2012. They look at DB plans and they make these hypothetical estimates for newly hired twenty-five year olds.

Mike: DB being defined benefits old-fashioned pension systems?

Amber: Right, not the other, newer kind. All right. Local trends that they found. First of all, the median state offers a lower nesting period so that's how long teachers have to be on before they can pass it, compared to several decades ago. It used to be ten years and now what do you think the average is?

Robert: Five?

Amber: Five. Bingo. Number two, states began lowering the normal retirement age in the 1990's and that continued into the 2000's but in recent years they have increased the retirement age, which obviously decreases benefits, which means fewer years to collect the pension. In 2012 alone, nineteen plans increased their normal retirement age from age fifty-five to age ...

Robert: Sixty-two and a half.

Amber: Yeah. What do you think?

Mike: Fifty-eight.

Amber: Fifty-eight. Did you peek over my shoulder?

Mike: I did not!

Amber: Number three. Average employee contribution rates remained relatively constant throughout the 80's 90's and 2000's but they increased after the recession and I didn't put those figures in there. Anyway, they're lowering the teachers net retirement compensation is the bottom line. Then they go into some stuff about new teachers and they basically say, "When benefits increase they increase to everyone, but when they get cut, they decrease only fro new workers," which we've had some other studies tell us that.

For example, couple little more factoids on this stuff. Although pension benefits for career teachers spend only only one percent from 1982 to 2012, teachers who were hired in 2012 ans stayed ten years, would qualify for an inflation-adjusted pension benefit worth one percentage less than their peers who began in 1982?

Robert: What a great question.

Mike: I don't know. Twenty percent?

Robert: I'm going to guess fifteen.

Amber: Twenty-five, you guys were both kind of close. All right, here we go.

Robert: That's a lot of money though.

Amber: Illinois, is our poster child for terrible pensions, right? An Illinois teacher would have to work ... give me a second to get the question. A new Illinois teacher would not be a positive return ... keep your teacher hats on ... would not see a positive return on their contributions unless she served more than how many decades in her system?

Mike: Oh, my gosh.

Amber: How long has she got to work before she sees retirement?

Mike: Three decades.

Amber: What do you think, Robert?

Robert: I would say that. About three.

Amber: Yeah. Well it's a little more than two decades. Both of you guys are in the ballpark. Last factoid the report closes with. We've heard this before but it's been a while. For every hundred dollars at states and districts contribute to teacher pension plans on average how many dollars goes toward paying down the pension debt?

Robert: No clue.

Mike: Yeah, I don't know.

Amber: Seventy dollars, so that's a lot. I think that was in Bob Strell's report for us as well. Anyway never good news on this topic.

Mike: It's so hard and ...

Robert: Germany could bail out a whole other country.

Mike: That's interesting. I was thinking about that as I had a little Twitter interaction with Mike Klonsky that somehow was about Greece and of course he's out there defending Greece. He's out there defending the Chicago Teacher's Unions too as the bankrupt the state of Illinois. Look, it's tricky because these pensions once they're in place, most state's courts are finding them to be constitutionally protected, which makes me think that what states are going to have to go after instead are going to be retiree healthcare, which is something that I think deserves some attention as well and I'm curious what the trends are there, particularly now that there's Obamacare that I can imagine more states saying, "You know what, teachers, once you're retired and before you are eligible for Medicare you are on your own when it come to that stuff."

Amber: Those are really accurate ability and union members, aren't they?

Mike: Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Amber: Those retirees?

Mike: Yeah. Yes they are.

Amber: Take it laying down, right?

Mike: They are not. All right well interesting and sobering.

Amber: Was it really Mike? Was it interesting?

Mike: It was interesting. I felt good about myself. I got many of those questions right. That made it interesting. It was definitely sobering. We don't need to do pensions again for a couple of months.

Amber: In a couple of months.

Mike: Okay, all right everybody. Hey! Go Pluto and until next time ...

Robert: I'm Robert Pondisico.

Mike: I'm Mike Petrilli. The Thomas B. Fordham Institute, signing off.

(Video may take a minute to load.)

There are no grand revelations, but this new report about New York’s robust charter sector from the city’s Independent Budget Office offers useful data on a range of hotly debated topics, including student demographics, attrition, and “backfilling” seats left by departing students.

For starters, it’s good to be reminded just how small that sector is, in spite of its rapid growth. Gotham boasts some of the nation’s highest-profile and most closely watched charters, including Success Academy, KIPP, and Achievement First, but only seventy-two thousand of the city’s 1.1 million school-aged children attend a charter school. And those major players are a fraction of the New York’s charter school scene, which is almost evenly split between network-run schools and independents. Some New York City neighborhoods are particularly charter-rich (Harlem, for instance, enrolls 37 percent of its students in charters as of 2013–2014), but charters remain relatively rare in the boroughs of Queens and Staten Island. The sector also serves an overwhelmingly black and Hispanic population. Charter students are more likely to be poor than traditional Department of Education (DOE) schools, though charters serve smaller concentrations of English language learners and special education students.

Another fascinating bit of data: The controversial practice of co-locating charters in DOE space is definitely contributing to overcrowding—in charter schools. Nearly 45 percent of charters have utilization rates over 100 percent, versus only 13 percent of DOE schools in co-located buildings.

The report is most noteworthy for filling a data vacuum in the contentious debate over “backfilling.” A report earlier this year called for New York’s charters to reduce long waiting lists by enrolling new students every fall when slots become available. “Some schools clearly choose not to fill the seats made available through student attrition,” the IBO notes, but “many fill all of their available seats or even add additional students to their cohort.” Backfilling declines after third grade, but even then, 80 percent of fourth- and fifth-grade charter school seats are filled. “To the extent you think backfilling is a problem, the data shows it's well on its way to being solved,” observed James Merriman, the head of the New York City Charter School Center. A notable exception is Success Academy, which largely eschewed backfilling in its upper grades until recently—and posts test scores that leave the rest of the city’s schools in the dust.

The IBO report won’t settle the noisy debates between charter boosters and critics in New York City—nothing short of an asteroid strike could accomplish that—but it’s a fascinating trove of data.

SOURCE: Raymond Domanico, “School Indicators for New York City Charter Schools 2013–2014 School Year,” New York City Independent Budget Office (July 2015).

A new study in the scientific journal Brain and Language examines how the brain responds when presented with two different methods of reading instruction. It examines a small sample—sixteen adults (with an average age of twenty-two) who are native English speakers and do not face reading disabilities.

Participants took two days to undergo training, whereby they learn an invented language based on hieroglyphics. Each participant was taught two ways to associate a set of words read aloud to a corresponding set of visual characters (or “glyphs”). The first was a phonics-based approach focusing on letter-sound relationships; the second was a whole-word approach relying on memorization. After training, the participants took part in testing sessions during which they were hooked up to an EEG machine that monitored their brain response. They were then instructed to approach their “reading” using one strategy or the other.

Scientists found that the phonics approach activated the left side of the brain—which is where the visual and language regions lie, and which has been shown in prior studies to support later word recognition. Thus, activating this part of the brain helps to spur on beginning readers. This approach also enabled participants to decode “words” they had previously not been exposed to in the training. The whole-word approach, on the other hand, did not activate the left brain hemisphere; instead, it engaged the right side, which has different circuitry typically not associated with “firing” in the brains of skilled early readers.

The study adds more solid evidence that phonics instruction is effective instructional practice, which is what the National Reading Panel told us many years ago. Now we know that it also stimulates the brain.

SOURCE: Yuliya N. Yonchevaa, Jessica Wiseb, Bruce McCandlissc, "Hemispheric specialization for visual words is shaped by attention to sublexical units during initial learning," Brain and Language, Volumes 145–146, June–July 2015.

Massachusetts and Ohio: Study in contrasts, am I right? One gave the country its handsomest president; the other birthed its most corpulent. One is a mecca for athletics, home to storied franchises that have piled on championships over the course of decades; the other’s teams have known defeat so cruel and so persistent that many suspect the influence of a wrathful deity. One has been the setting of cherished cultural touchstones of television and film; the other is not so much like that. (What’s that? I’m from Boston, why do you ask?)

But when it comes to education, the two have more in common that you might imagine. Last week, Achieve released detailed profiles of each state’s career and technical education (CTE) programs. The reports arrive at a turning point in the history of workforce training, as noted policy commentators are beginning to embrace vocational instruction as an underutilized tool for spurring upward mobility. CTE students, we now know, are just as likely as students on a college preparatory track to pursue postsecondary education; what’s more, their starting salaries after obtaining associate’s degrees and professional certifications are impressive enough to make this liberal arts major weep bitter tears into his Deleuze.

It wasn’t always this way, however. For years, students in many career and technical programs were the unlucky recipients of a second-class education. As the authors write in their Ohio entry, “The schools offered limited programs; put students on separate, narrowly focused tracks; provided only high school-level credit; and trained graduates for a specific occupational skill set.” It has taken about ten years of commitment to high expectations and challenging coursework to turn the Ohio CTE sector around, including a move in 2012 to begin issuing report cards for each of the state’s ninety-one career-technical planning districts. Legislation passed last year further mandates that career-track graduates must either achieve a cumulative passing score on seven end-of-year course assessments, be judged “remediation free” on a nationally recognized college admission exam, or earn an industry credential that will allow them to find rewarding employment without a college degree.

Like its Rust Belt counterpart, the Bay State has also taken major steps to transform a benighted vocational system into a wide-ranging network of schools that graduate more of their charges into competitive colleges and fulfilling careers. The paramount feature of Massachusetts CTE is lofty standards: Since 2003, students enrolled its thirty-eight schools have had to pass the rigorous MCAS exams in English and math before earning their diplomas. Top-performing programs like Essex Technical High School now deliver a kind of double-duty curriculum that provides the requisite grounding in traditional subjects while also allowing students to explore their interests in fields like robotics, health sciences, IT, and precision manufacturing. Though the commitment can be daunting for students, the promise of a genuine career path has led to stupefyingly low dropout rates.

Thankfully, CTE has begun to overcome its justifiably dubious reputation. By setting kids up for professional success in atmospheres of academic legitimacy, career and technical programs could become one of the most valuable items in the education reform toolbox. Now if only the city of Cleveland could establish some kind of quarterback academy.

SOURCES: “Best of Both Worlds: How Massachusetts Vocational Schools are Preparing Students for College and Careers,” Achieve, Inc. (July 2015); “Seizing the Future: How Ohio’s Career and Technical Education Programs Fuse Academic Rigor and Real-World Experiences to Prepare Students for College and Work,” Achieve, Inc. (July 2015).