Partnership schools: The hundred-year-old start-ups

Let’s not break those things about Catholic schools that make them effective. Kathleen Porter Magee

Let’s not break those things about Catholic schools that make them effective. Kathleen Porter Magee

Editor's note: This post is the second in a series reflecting on the author's first year as superintendent at the Partnership Schools, a nonprofit school management organization that (thanks to an historic agreement with the Archdiocese of New York) was granted broad authority to manage and operate six pre-K–8 urban Catholic schools.

Last week, Eliza Shapiro published an article at Capitol New York that explored the “charter-like” approach the Partnership for Inner-City Education is bringing to its Catholic schools. In many ways, that characterization is true. We are, after all, partnering with some pioneers from the charter world. And we’re implementing many of the best practices that so many of us have learned from the most successful CMOs.

At the same time, though, there is a lot that it misses. We are much more than “charter-like schools”; we’re Catholic schools. And our rich history is the foundation of what we do. Some of the differences are obvious: We can wear our faith on our sleeve and teach values unequivocally. We teach religion. We prepare students for the sacraments. We operate on shoestring budgets.

But there are other differences that have a more subtle—but perhaps more profound—impact on the work that Catholic schools have had on their students and their communities.

For starters, Catholic schools in general (and the Partnership Schools in particular) are deeply rooted in the communities they serve. We call our schools “hundred-year-old start-ups” because as much as we seek to embrace the entrepreneurial spirit of charter schools, we know that we are also stewards of deep community roots that were planted long ago.

Our schools were initially founded to serve Catholic families and students who had been neglected by a traditional school system openly hostile to their faith. One hundred fifty years ago, the only way Catholics in New York City could secure an education for their children was to accept indoctrination in Protestant values as part of an overtly anti-Catholic agenda pushed by the city’s elites. Parishes responded by creating an entirely new and different system of schools that welcomed not just Catholics, but anyone who wanted an alternative to traditional public schools.

This effort often included a special outreach to African American and Latino students, as well as others who had been marginalized. From the beginning, we were a community of outsiders who drew strength from our belief that all students deserve a school that makes them feel welcomed. These parish schools have been heavily subsidized since their founding by the church community so that, as much as is possible, finances aren’t an obstacle to any family who wants a different education for their child.

These are schools born from, nurtured by, and sustained through rich interactions with the communities they serve. It’s hard to tell sometimes where the school ends and the community begins. The schools wouldn’t be the same without the communities. And the communities, as we’ve recently learned from Margaret Brinig and Nicole Garrett’s work in Lost Classrooms, Lost Communities, suffer without the schools.

Something special happens in schools rooted in enduring relationships and timeless values. Far beyond what their initial test scores might predict, students in Catholic schools tend to experience strong and lasting results. They graduate from high school at greater rates, are much more likely to complete college, often enjoy more stable marriages, and are more likely to be civically engaged and give back to their communities as adults.

These are schools with a mission and a lot to offer the communities they serve, but by most standard input measures, our schools would fare badly. We are poorly resourced and spend very little per pupil. Our class sizes are big compared to traditional public schools. Our teachers are paid less than their traditional public and charter peers. And we have far less in the way of flashy technology and “innovation” than you’d come to expect from a high-quality school.

Yet if I’ve learned anything over the course of the past year, it’s this: Looking at Catholic schools only through the lens of what we have come to expect from traditional or charter school models misses much about what makes them special. Yes, they need to improve in some fundamental ways. But that improvement will come by building upon their unique strengths rather than trying to Xerox the habits and practices of high-performing competitors.

Here are two key lessons I’ve learned about how the reform approach in these hundred-year-old start-ups needs to look different:

Turnaround, not turnover

Increasingly in the traditional and charter school world, school turnarounds have become synonymous with turning over teaching staff. When operating within a large public bureaucracy, that’s one way to spur what’s necessary to drive change. When it comes to turnaround proposals, the more “serious” the plan, the more “fresh blood” will be often brought into a school.

While it may well be necessary elsewhere, that approach would have caused us to overlook the very real strengths we’ve found in our schools, starting with teams of teachers who are as committed to the mission of our schools as they are talented.

One of the things that has been most exhilarating about my first year at Partnership Schools is the amazing instructional growth and buy-in we’ve seen. Some of our greatest success stories so far have come from teachers who don’t perfectly fit with the reform narrative that has emerged elsewhere.

Take, for instance, the middle school English language arts (ELA) teacher I mentioned in my last post, whose students recorded our highest achievement on the New York ELA test last year. (Early results indicate that she knocked it out of the ballpark again this year.) She is a forty-year veteran in the archdiocese, a devout Catholic, and a loving Latina with a high school degree and a passion for literature. She wouldn’t pass the certification barriers elsewhere, but forcing her out would have been a real loss to our students and our community.

Similarly, the fifth-grade teacher whose students demonstrated the most significant growth (as measured by our curriculum-embedded and interim math assessments) is a twenty-five-year veteran. After my first observation with her, I joked that she was “teaching like a champion” two decades before Doug Lemov sat down to write his book (a fact that would surely not surprise Doug, who has long said that he merely names and describes what great teachers already do).

While the strengths of experience are often overlooked in education reform, our teachers also confound the traditional school belief in credentials. Our highest-performing sixth-grade teacher is a young mother who just wrapped up her third year teaching. The summer after she graduated from college, she walked into St. Athanasius—inexperienced and with few job prospects—and asked the principal to give her a chance, even though she had no formal experience or preparation. Marianne Kraft (a principal with more than forty years’ experience at her school) had a good feeling, gave her that shot, and has never looked back.

I share these stories not just because they’re amazing and humbling, but also because we might have mistaken some of our very real strengths for weaknesses had we not filtered other schools’ “best practices” through the unique lens of our communities, our teachers, and our students. Catholic school reformers need to look with more discriminating eyes than that.

Stewardship, not ownership

The Partnership doesn’t own these six Catholic schools; they have been owned by their communities from the beginning. Our task is one of stewardship: to help make them as relevant and successful today as they were one hundred years ago and ensure that they will be relevant still one hundred years from now.

That doesn’t mean we are any less committed to securing near-term results. But it does mean that we combine the urgency of now with a longer view of the role these “cathedrals of learning” will play in the lifespan of our students and generations to come.

The power that comes from a deeply felt spiritual mission is unlike anything I have seen in education reform. The passion our teachers feel for their schools, for their students, for their principals, and for their communities is palpable. We see this passion and commitment in countless ways. Sometimes they manifest in respectful but forceful pushback to new ideas that aren’t well explained or rolled out. In other instances, they create the buy-in we get from teachers who see our curricular and instructional changes for what they’re meant to be—ways to support them in their efforts to serve their students.

Catholic school reform must be different from the education reform we have seen elsewhere, because the strengths of our schools are different, and our challenges are unique. We will never have as much money as our charter and traditional public school peers, which means that we will always need to find creative solutions in our quest for excellence. And it’s important to remember that, as we’ve seen throughout our history, many of the constraints we’ve faced have forced choices that make our schools great.

In other words: As we bring in best practices from our charter and traditional public school peers, we should be careful not to break those things about Catholic schools that make them effective. In the end, it’s clear that schools born in communities of faith are different. By embracing that difference, we will achieve the results that our students deserve.

As ESEA reauthorization heads to conference committee, debate is certain to center on whether federal law should require states to intervene if certain subgroups are falling behind in otherwise satisfactory schools. Civil rights groups tend to favor mandatory intervention. Conservatives (and the teachers’ unions) want states to decide how to craft their school ratings systems, and when and how to take action if schools don’t measure up. The Obama administration is siding with the civil rights groups; a recent White House release, clearly timed to influence the ESEA debate, notes that we “know that disadvantaged students often fall behind in higher-performing schools.”

But in how many cases do otherwise adequate schools leave their neediest students behind? Are there enough schools of this variety to justify a federal mandate? Fortunately, we have data—and the data show this type of school to be virtually nonexistent.

In a recent post, I looked at school-level results from Fordham’s home state of Ohio. That analysis uncovered very few high-performing schools in which low-achieving students made weak gains. (“Low-achieving” is defined as the lowest-performing fifth of students statewide.) Just seven schools (in a universe of more than 2,300) clearly performed well as a whole while allowing their low-achievers to lag far behind.

But perhaps Ohio’s data are an anomaly. Or maybe the low-achieving subgroup results don’t tell the full story. (Ohio doesn’t break out growth results by race or by economic disadvantage.) So I looked for another state that disaggregates student growth results by subgroup.

Surprisingly, twenty-three states do so—an impressive number that demonstrates the improvements states are making in school accountability systems. Colorado is one such state, and it has an extensive but navigable reporting system. It also disaggregates results for seven different student subgroups—the most we observed in our fifty-state review. Colorado employs the Student Growth Percentiles (SGP) methodology to measure student growth. SGP utilizes longitudinal, individual student data and statistical methods to calculate learning growth over time, a similar but not an exact equivalent of Ohio’s value-added model.

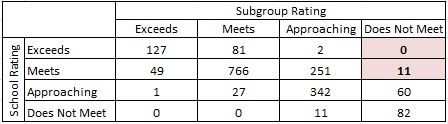

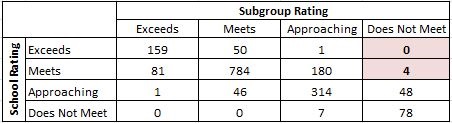

When we look at the school-level results from Colorado, a story similar to Ohio’s emerges. Only a small number of highly rated schools, as measured by growth on state exams, appear to leave disadvantaged students far behind. In fact, just eleven schools—less than 1 percent of those rated—perform well overall, while also receiving the lowest rating for their Free or Reduced-Price Lunch (FRPL) students. Only four schools do well overall while receiving the lowest rating for their minority students.

Table 1: Number of schools receiving each combination of overall and subgroup growth ratings in reading, Colorado schools, 2013–14

(A) Overall versus FRPL student subgroup ratings

(B) Overall versus minority student subgroup ratings

Source: Colorado Department of Education

Notes: The numbers of schools included in Tables 1A and 1B are 1,810 and 1,753 respectively. Colorado has four rating categories, from lowest to highest: “does not meet,” “approaching,” “meets,” and “exceeds expectations.” The ratings are assigned based on a school’s median growth percentile scores and whether the school has made “adequate” growth; for more details on the school rating procedures, see this document. “Minority student” denotes any non-white student—the state does not decompose a school’s minority subgroup rating by specific race or ethnic group.

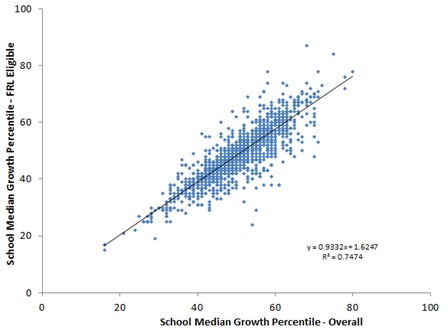

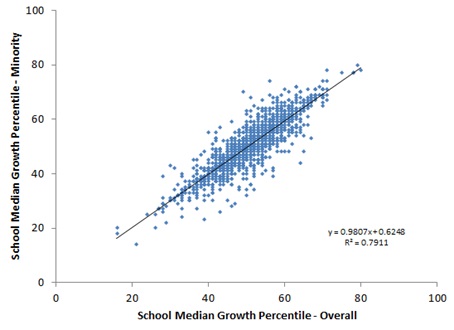

Consider also the charts below, which display the relationship between a school’s overall and subgroup growth scores in numeric terms. You’ll notice a remarkably strong correlation between overall and subgroup performance. (Of course, some schools have a large fraction of disadvantaged or minority students; for those schools, we’d expect a near-perfect correlation.)

Chart 2: Correlation between overall and subgroup growth scores in reading, Colorado schools, 2013–14

(A) Overall versus FRPL student growth scores

(B) Overall versus minority student growth scores

Source: Colorado Department of Education

Notes: A school’s median growth percentile is reported on a scale of 1–99, based on a three-year average; a higher value indicates that a group of students—either an entire school of students or a subgroup—is making relatively more progress than its peer group (e.g., a median value of 80 indicates that the group’s growth outpaced 80 percent of its peers); a lower value indicates that the group made less progress. See here for more information. The numbers of schools included in Charts 2A and 2B are 1,810 and 1,753, respectively (some schools receive an identical combination of values, so the actual number of points displayed doesn’t match the n-count). Elementary, middle, and high schools are included. Correlation coefficients are 0.86 and 0.89 for FRPL and minority subgroups, respectively. The correlations for math, not displayed, are not substantially different from the reading results (0.89 and 0.93 for FRPL and minority subgroups, respectively).

The evidence from Colorado and Ohio suggests this general principle: Good schools are usually good for needy children (and, conversely, bad schools are bad for them). The NCLB-era concern about schools’ averages masking poor subgroup performance goes away if we measure school effectiveness the right way—via student growth rather than proficiency rates.

Still, like Ohio, Colorado has a few outlier schools—those that perform well overall but poorly for disadvantaged groups. One Colorado school, for example, had an overall score of 54—slightly above-average progress for all students—but a score of 24 for its FRPL-eligible students. States are absolutely right to identify such outliers, and local educators, parents, and citizens should be alarmed about the discrepancy in results.

As federal lawmakers weigh intervention policy options, though, they should reflect on the evidence from Ohio and Colorado. The number of otherwise-satisfactory schools where disadvantaged students lag behind is vanishingly small. (So trivial is the number of such schools that the administration’s claim, cited above, that this occurs “often” should be called into question.) Should federal lawmakers create a nationwide, one-size-fits-all school intervention policy based on isolated cases? Not in my view; it would be like mandating hurricane drills in Kansas.

The importance of vocabulary, ESEA reauthorization efforts, school discipline, and how school environment affects teacher effectiveness.

Amber's Research Minute

Matthew A. Kraft and John P. Papay, “Can Professional Environments in Schools Promote Teacher Development? Explaining Heterogeneity in Returns to Teaching Experience,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, Vol. 36, No. 4 (December 2014).

A new study by Dan Goldhaber and colleagues provides loads of descriptive data that document the extent and depth of the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students. Dan and many others have produced research that repeatedly shows that disadvantaged kids get the short end of the stick when it comes to high-quality teachers. But the bottom line of this latest study is that this inequitable distribution of teachers plays out no matter how you define teacher quality (experience, teacher licensure exam score, or value-added estimates) and no matter how you define student disadvantage (free-and-reduced-priced lunch status, underrepresented minority status, or low prior academic performance).

The analysts use grades 3–10 data from Washington State for the 2011–12 school year. They target fourth-grade classrooms in particular, then replicate their analysis for the elementary, middle, and high school levels.

Here’s a summary of their findings: The distribution of prior-year value-added estimates for teachers of students on free and reduced-price lunch is routinely lower than the distribution for fourth graders who aren’t eligible for the lunch program. Low-income fourth graders are also more likely to have teachers who earned lower scores on the teacher licensure exam. Worse, the distribution of low-quality teachers is most inequitable within the most disadvantaged districts.

These trends continue in seventh grade. For example, almost 20 percent of low-performing seventh-grade math students are assigned to teachers with low prior year VAM estimates—versus just 7 percent for high-performers. And the average experience of a seventh-grade minority student’s teacher is 1.75 years less than the average experience of a white student’s teacher—who also scores roughly 4–5 points higher on the licensure exam.

In short, disadvantaged kids are less likely to be taught by high-quality teachers in nearly every grade level. These trends are driven mostly by teacher sorting across districts and schools rather than across classrooms in schools, though inequities exist at all levels. A number of factors could be driving these trends, starting with the fact that many teachers prefer working in whiter, lower-poverty schools. Union contracts that abet the movement of senior teachers to such schools are also part of the problem.

SOURCE: Dan Goldhaber, Lesley Lavery, and Roddy Theorbald, "Uneven playing field? Assessing the teacher quality gap between advantaged and disadvantaged students," Educational Researcher (June 2015).

Education reformers talk a lot about providing disadvantaged kids access to great schools, and for good reason. Countless institutional barriers exist to thwart students from choosing the best nearby schools, and solutions like open enrollment and private school scholarships are justly lauded as escape routes for families caged by circumstances of class.

But there are also much more literal obstructions to educational choice, and they aren’t arrayed solely against low-income learners trapped in huge, failing urban districts. To choose just one example, children enrolled in rural and remote schools—separated by hundreds of miles from the auxiliary services available in many cities, and usually passed over by the most sought-after teaching talent—are simply subjected to geographic dislocation instead of (or often in addition to) economic deprivation.

This new report by the Foundation for Excellence in Education (which has already released one worthy analysis of the issue) looks at the successful implementation of state-level course access policies by ten districts and charter management organizations across the country. The programs bring outstanding options to students who would otherwise have trouble finding them—typically through online tools that offer academic relief to district budgets, but also by incorporating embedded resources like local trade schools for in-person career and technical instruction. The possibilities they present are exciting.

The case of Guthrie Common School District perfectly encapsulates the benefits of course access for rural communities. Located in tiny Guthrie County, Texas (a lilywhite dot on the panhandle that counts as the third-least-dense county in America), the district currently serves exactly ninety-one students. After years of struggling to attract foreign language instructors, educators there partnered with the language software company Rosetta Stone to create a comprehensive set of Spanish courses. Its growing slate of offerings, known as the Guthrie Virtual School, now employs ten teachers, both inside and outside Texas, and is used by some 850 students around the state.

The situation couldn’t be more different in Palm Beach, Florida, home to nearly 185,000 students and the eleventh-largest school district in the country. Rather than relying on third-party providers to supplement an otherwise-meager curriculum, its schools take advantage of virtual teaching to cater to the many competing needs on order. Palm Beach students—far more diverse, more in need of financial supports, and more likely to stumble on the way to graduation than their Guthrie County counterparts—can use course access to seek out classes that wouldn’t normally fit with their schedules; kids transferring into the district can find outside providers to help recoup credits and catch up with their new classmates; and high-fliers can take part in more advanced course options in middle and high school. The concept of broad selection and availability, in other words, isn’t just a boon to those in rural hamlets.

Course access is a critical piece of the reform puzzle because it reflects and affirms the fundamental virtue of choice: Schools and students alike can choose the kind of education that best fits their constraints, their priorities, and their ambitions. Whether you’re clutching a surfboard or a mechanical bull, that’s pretty appealing.

SOURCE: “Leading in an Era of Change: On the Ground: How Districts and Schools Can Make the Most of Course Access,” Foundation for Excellence in Education (July 2015).

This book out of Harvard’s Public Educational Leadership Project (PELP) takes on one of the biggest challenges in managing school districts: the relationship between the central office and schools. In meeting needs that vary from building to building, do certain governance structures work better than others? For example, is it better to centralize and make all the decisions “downtown” or decentralize and give autonomy to schools?

Researchers analyzed five large urban districts in four states with varying approaches to their central office/schools relationships, all of which were selected based on improvements in student achievement. The districts shared other similarities, such as serving a wide range of schools and communities, and each enrolled more than sixty-thousand students (mostly of color). PELP’s methodology is best described as a case study approach that included combing through news sources and research reports and interviewing sixty-three district and school leaders.

Researchers reached a perplexing conclusion: Both styles can be successful if the central office and school coordinate their systems, strategies, and visions. Whether centralized, decentralized, or a blend of both, structure has no bearing on student performance. Instead, all that matters is that both parties openly communicate and readjust in order to figure out what is actually working and removing what is not. Some tension is certainly to be expected between the priorities of a school and those of a central office. But working together will produce more productive results than operating as if it’s a zero-sum game. This is what the authors mean by “coherence”—commonsensical solutions that strive to align rather than divide.

Principals ought to play an important role in this because, in addition to having an inherent allegiance to their own institutions, they also understand their schools’ unique needs and challenges. For example, in the more centralized Aldine Independent School District, the central office relied on intermediaries (or area superintendents) to build collaborative relationships with principals. This type of partnership gave principals more of an active role in making decisions. Simultaneously, central offices were able to check the progress of their proposals and receive feedback from those who know their schools best.

The book also explores the importance of organizational culture. A supportive culture can reinforce a district’s strategy, while a toxic one can derail policies. Here “culture” refers to the actual norms that influence individuals’ actions at the school level versus what the central office says should happen. School districts tend to dismiss culture as frivolous in decision-making processes, or else mistakenly assume that culture is static. That’s a mistake, say the authors. And districts that take it seriously see results.

Consider the Long Beach Unified School District, which prioritized improving its academic program. Rather than rolling out initiatives in a top-down approach, the central office encouraged schools to pilot their own projects. Teachers and principals had the opportunity to tweak and revise programs to determine if they should come to fruition. The result was a success. Unsurprisingly, when individuals are invited into the decision-making process and have their voices heard, they are more likely to be invested in implementing the changes they helped to plan.

In the end, the general takeaway is that districts must recognize that there’s no best strategy for governance; instead, the best path is one that strives for coherence in a given environment.

SOURCE: Susan Moore Johnson et al., Achieving Coherence in District Improvement: Managing the Relationship Between the Central Office and Schools (Cambridge: Harvard Education Press, 2015).