On Constitution Day, in search of the public mission of schools

When school boards describe their missions, they often overlook citizenship. Robert Pondiscio and Kate Stringer

When school boards describe their missions, they often overlook citizenship. Robert Pondiscio and Kate Stringer

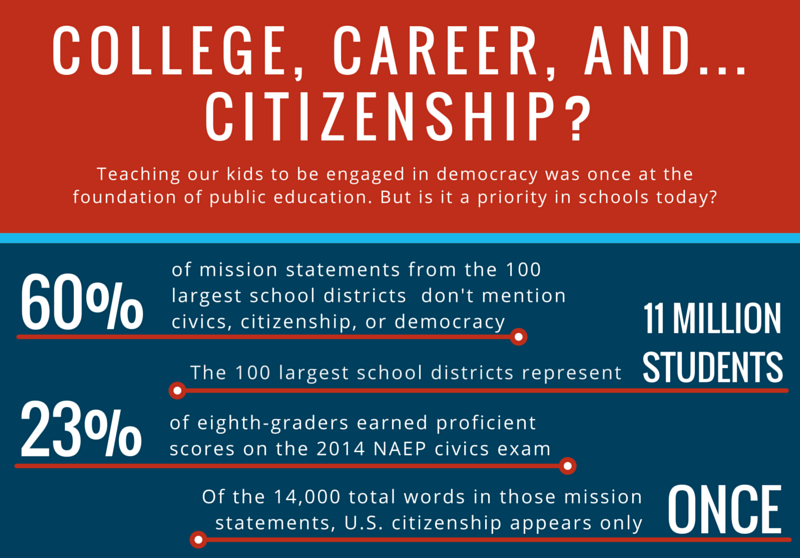

Tomorrow is Constitution Day, when all schools receiving federal funds are expected to provide lessons or other programming on our most important founding document. But when only one-quarter of eighth graders score “proficient” on the most recent NAEP civics exam, it’s also a reminder of how rarely civics and citizenship take center stage in America’s public schools.

The public-spirited mission of preparing children for self-government in a democracy was a founding ideal of America’s education system. To see how far we have strayed from it, Fordham reviewed the publicly available mission, vision, and values statements adopted by the nation’s hundred largest school districts to see whether they still view the preparation of students for participation in democratic life as an essential outcome. Very few do. Well over half (fifty-nine) of those districts make no mention of civics or citizenship whatsoever in either their mission or vision statements.

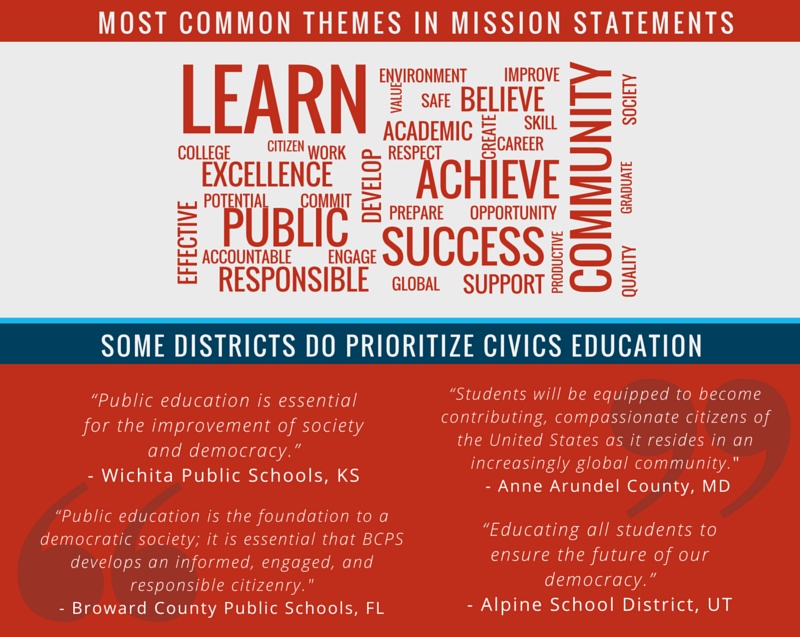

The personal and private reasons for education—preparation for college and career, for example—are much more on the minds of school district officials who write and adopt these statements and goals than the public virtue of citizenship. The words “college” (thirty-seven occurrences) and “career” (forty-six), for example, easily outnumber “civic” (eight) and “citizen” (twenty-eight). For comparison, the most commonly occurring words are, unsurprisingly, “student” (433), “school” (250) and “learn” (175).

The fourth-most-used word, “community” (141), could be viewed as a proxy for citizenship. However, that term most frequently occurs in bromidic phrases like “community of learners,” or refers to what the community can do for students rather than what the students are expected to do for the community. The San Diego Unified School District mission statement, for example, includes this phrase: “Engages parents and community volunteers in the educational process.” Nurturing a supportive community is not a bad goal; it’s simply not the same as preparing students for active participation as citizens.

To be sure, some districts’ mission statements demonstrate a clear focus on preparing students for citizenship, or establish it as an equal priority with more personal goals:

By contrast, Montgomery County, Maryland, doesn’t even acknowledge a civic role. Its mission statement reads, “Every student will have the academic, creative problem solving, and social emotional skills to be successful in college and career.” Neither is there any mention of civics or citizenship in the vision statement or the district’s “core purpose,” which is this: “Prepare all students to thrive in their future.”

Unsurprisingly, a substantial number of mission and vision statements are either meaningless homilies or bland statements seemingly calculated to be inoffensive.

Some terms are conspicuous in their absence. The words “patriotic” and “patriotism” do not appear at all in any of the hundred districts’ public statements that we reviewed. Only two districts—Wichita Public Schools in Kansas and Utah’s Alpine School District—include the word “democracy” (Eight mention the word “democratic.”). Maryland’s Anne Arundel County is the only district that specifically mentions U.S. citizenship in its mission or vision statement. (“Students will be equipped to become contributing, compassionate citizens of the United States as it resides in an increasingly global community.”) Perhaps most surprising of all: The words “America” and “American” appear in none of the hundred mission and vision statements. However, “global” appears in the statements of twenty-eight districts—usually in phrases like “global society,” “global economy,” or “global citizens.”

In fairness, a district’s mission statement may not offer much insight into the nature of its instructional practices, the civic values that are communicated to students, or the full range of outcomes sought by each school system. But at some point, leaders and stakeholders in each district sat down and attempted to craft and approve a set of ideals, values, and goals that ostensibly reflect the aspirations of their communities. Thus mission statements offer a window into our evolving view of the purpose of education.

The mission statement of the Alpine, Utah, school district, which serves twelve municipalities outside Provo, is a good example. It was approved by its board of education in 2003 and places a premium on “educating all students to ensure the future of our democracy.” A set of goals adopted more recently includes “civic preparation and engagement.” District administrator David Stephenson says that the mission “is aligned with what we do in the classroom. We obviously follow state core curriculum civics instruction. We follow state law on what we teach. It’s really aligned well with that curriculum.”

“The mission statement is not made by random people on a Tuesday afternoon. It’s the community, building principals, school administrators, parents, teachers, superintendents. All of our adult stakeholders were represented in crafting a mission that best represents our community,” says Andy Jenks, a spokesman for Henrico County Public Schools in Virginia. “We do think it’s important. In some cases it might be the first thing somebody reads about our organization.”

The National Assessment of Educational Progress lists five dispositions it says are “critical to the responsibilities of citizenship in America's constitutional democracy.” These are active, not passive roles: respecting human worth, responsible participation, promoting a healthy democracy. If these aren’t priorities of a school district, are they priorities of their students? The data says no. Of the eighth graders who took the NAEP’s civics exam in 2014, only 23 percent scored proficient marks.

If a school districts’ mission and vision statements are any indication, such uninspiring results are also unsurprising. They simply mirror the priorities established at the local level for K–12 education, where preparation for citizenship is not a high priority.

On Constitution Day, it’s worth asking whether it is time to restore the public mission of public education to its rightful status as a priority for our schools.

Robert Pondiscio is Fordham’s vice president for external affairs. Kate Stringer is an editorial intern.

___________________________________

Download the full infographic:

Remember all those pitched battles and screaming matches over Common Core? The furious charges of federal overreach? The demands to "repeal every word" of it? As children return to school across the country this week, Common Core remains largely intact in more than forty states. At the same time, new evidence suggests that the much tougher Common Core challenges—the ones emanating from inside classrooms—have only just begun.

Results from the initial round of Common Core-aligned tests (administered last spring) have been trickling out for the past few weeks in more than a dozen states. The results have been sobering, but not unexpected. Recall that the No Child Left Behind years were an era of rampant grade inflation. States whose students performed poorly on the benchmark National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) routinely rated the vast majority of their students on or above grade level, simply because states were allowed to set their own bar for success and thus had a perverse incentive to declare ever-greater numbers of kids proficient. The result was a comforting illusion of student competence that was shattered when "proficient" kids got to college and needed remediation, or entered the workforce with substandard skills. Common Core testing, if nothing else, is supposed to make it harder to tell self-serving lies about where kids actually stand.

A report last week from the Education Trust didn't command as much attention as the test scores, but it's arguably even more important. An examination of assignments given by middle school teachers appears to show that most of the work asked of students does not reflect the higher, more rigorous standards set by Common Core. Fewer than 40 percent of assignments examined were aligned with grade-appropriate standards. If the study sought to show where teachers are in their understanding of the higher standards, the answer appears to be "not very far along."

"This is why we support college- and career-ready standards to begin with," says Education Trust's Sonja Santelises, one of the report's authors. "We knew we needed more cognitive, intellectual challenges in what we're asking kids to do."

A couple of caveats are needed. First, the report is a small-scale pilot study of assignments at six middle schools in two urban districts—a tiny and unrepresentative sample. Additionally, more than half of the assignments reviewed came from science and social studies classes, where teachers might have had learning goals that were not readily apparent to reviewers looking for examples of students grappling with complex texts. Thus, the Education Trust may be inadvertently painting an overly pessimistic view.

Still, the dour findings ring true with those who have worked with school districts training teachers to understand and adopt the instructional shifts expected under Common Core. One veteran public school teacher and staff developer worries that we are paying the price for years of "de-professionalizing" the teacher work force. "'Do these things, use these moves and you'll be successful'—that's been the message to teachers for the past fifteen years," she says. "Many teachers throw up their hands and say, 'Just tell me what you want me to do,' or, 'Is this the right way?'"

The challenge is complicated further when elected leaders lack the political will to hold the line on higher standards, sending mixed signals to teachers. New York Governor Andrew Cuomo recently announced a "review" of Common Core, which he insists is "not working and must be fixed." The announcement left proponents of the standards scratching their heads, since New York's Common Core implementation has been held up as a national model. Cuomo's move appears to be an attempt to mollify angry parents who have refused to let their children take the new Common Core tests. However, that discontent almost certainly has more to do with Cuomo's double-whammy policy of insisting that teachers be held accountable for test scores when they're already struggling to meet higher standards. It's simply unreasonable to expect teachers to change their practices dramatically and demand an instant boost in test scores at the same time.

Adopting higher standards is easy. Complaining about them is even easier. The bottom line is that while the overheated debate over Common Core has raged on, far too little attention has been paid to the heavy lift being asked of America's teachers—and the conditions under which they are being asked to change familiar, well-established teaching methods. Meeting those higher standards is agonizingly difficult work. It requires patience and realism, two things that have never been particularly abundant in American education.

Editor's note: This post was originally published in a slightly different form at U.S. News & World Report.

gjohnstonphoto/iStock/Thinkstock

D.C.’s gender gap at top schools, mission statements, neighborhood school attendance boundaries, and test-based retention.

SOURCE: Guido Schwerdt, Martin R. West, and Marcus A. Winters, "The Effects of Test-Based Retention on Student Outcomes Over Time: Regression Discontinuity Evidence from Florida," National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 21509 (August 2015).

Mike: Hello, this is your host Mike Petrilli of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute. Here at the Education Gadfly Show and online at edexcellence.net and now please join me, welcoming my co-host the Marcus Mariota of education reform, Robert Pondiscio. Who? He's this guy, a quarterback who had an amazing day on Sunday.

Robert: Really?

Mike: I guess the best debut of an NFL quarterback in history.

Robert: He's new, okay.

Mike: He's new.

Robert: I'm frankly not paying a bit of attention to football right now, because, there's this baseball team from New York that has as we speak a 9-1/2 game lead over some other baseball team from Washington called the Mosquitoes, the Gnats.

Mike: Well, the good news here Robert is that it is true. The Gnats have fallen. That is a little a bit sad. The good news is that the Mets will eventually have to play the St. Louis Cardinals. How many world championships do the Mets have? I don't think it's in the . . .

Robert: I think I hear my mother calling me.

Mike: I don't think it's in the two figures.

Robert: I've got to go.

Mike: Like the Cardinals. The Cardinals are know as being obnoxious fans. I will not be an obnoxious St. Louis Cardinal's fan. I will only say, that it's going to be a great post-season for baseball. Looking forward to it.

Robert: I am too. It's just nice to be invited to the dance for the first time in oh I don't know, 20 some odd years.

Mike: Isn't it true that you still have a worse record than the Chicago Cubs?

Robert: Yeah, yeah, yeah.

Mike: How amazing is that?

Robert: It's true.

Mike: They're going to be in third place in their division. This is not the Major League Baseball Podcast, though I think Robert and I would both love to do that.

Robert: I would love that.

Mike: My son Nico would love to be on too. He could tell you about all kinds of things. We check the standings every day. This is your chance, our loyal listeners to hear about the latest in education reform. Without further ado, Clara let' play Pardon the Gadfly.

Clara: Mike, a blog post of yours brought attention to the gender gap in some of Washington D.C.'s top high schools. Is this another form of creaming? Is it time for affirmative action for boys?

Mike: Ah-hah. It was interesting Robert, I got this idea, because, there's been all this press about how boys are doing so much worse than girls in our education system, especially when you look at the college enrollment and completion numbers. Famously, you've got some of these colleges now where something like 55%, 60%, 65% of the graduates are women.

Robert: Are women, yeah.

Mike: This is having an impact on all kinds of things in our society including even the dating scene. There's a new book out, that the guy bills as the least romantic book on dating and marriage, ever. It's something like Date-onomics. I think it's called.

Robert: College educated women want to marry college educated men.

Mike: They do and there aren't enough to go around. In a place like Washington D.C., it's something like three college educated women for every two college educated men, yes.

Robert: My daughter is about to go off to college, when she brings home a boyfriend, he better have a good GPA and be on his way to graduating or, otherwise, we're going to be having some problems.

Mike: Yeah, but the problem is she'll be lucky to find a guy like that is the point, because, there's not many of them around. Long story short. I was wondering, how does this play out in high schools. I looked here in D.C. There's some great data. They've got these equity reports that make this pretty easy to answer. Lo and behold, there are something like five or six high school, actually five or six schools in D.C. that have more than 60% of their populations female. One is a new all girls charter school.

Robert: Throw that one aside.

Mike: Set that one aside. The others are all high school and they're all selective admissions or charter schools. D.C. has an Exam School, Benjamin Benneker that for a long time has been a historically black high school, African-American school and very well regarded in the city, 75% female.

Robert: Wow.

Mike: Then there's a performing arts school, also another school called the School Without Walls, which the kids have a funny name that they call that, that's not family appropriate. The School Without rhymes with walls.

Robert: Okay, I think I get . . .

Mike: That' what the kids joke about, so anyway long story short. Then the Kipp School. Thurgood Marshall Charter School.

Robert: It's a real good point.

Mike: When it comes in particular to the selective admission schools, a Benneker school. This is like the Stuyvesant of Washington D.C. It's an exam school. The kids have to test at a certain level, plus recommendations and other things to get in, 75% girls.

Robert: Yeah.

Mike: Now if they're more qualified than the boys, you could say then, that that's just the way the cookie crumbles, right?

Robert: Sure, but on the other hand at some point you have to ask some very hard questions about what is it about our K-12 system, whether it's traditional or schools of choice and charters, that seems to be, italicize seems to be failing young men.

Mike: Well now, hold on Robert. You went right to the school system, right? Can't you say that there's, there could be other issues.

Robert: Sure.

Mike: A lot of, most kids in D.C. or at least an overwhelming number are growing up in poverty or near poverty. They may be growing up in single parent families and we do know from some good research now, that boys have a harder time in those female headed households than do girls.

Robert: No, no. I don't want to paint with too broad of a brush, but your piece and a similar piece in the Washington Post, made me wonder and I have not looked up the answer. Maybe you have. Much has been made of our increase in high school graduation rates over the last decade. Something that I looked into a few weeks ago that interested me was credit recovery. How much of that we don't know, of that enhanced graduation rate is credit recovery. I'm now wondering how much of it is boys? Do we have a Finland issue on our hand here. You know how in Finland when you take the boys out of the picture Finland looks great. When you look at boys they're mediocre, right? Is that what's happening here?

Mike: Right. Then you're saying what we've gotten better at graduating girls than than boys, not as well graduating boys?

Robert: I don't know the answer, but that's my question.

Mike: Yeah, and that's what's partly behind these numbers. There's not doubt that part of the reason some of these schools are imbalanced is more boys do drop out in D.C. than girls. They also end up more at the schools for the trouble kids.

Robert: Yeah.

Mike: Also some of the vocational schools. That one you can kind of make sense out of. Also some of the big comprehensive high schools are heavily male. Is that because of the sports? Is that just because those schools become in effect, the school of last resort for kids that can't find their way anywhere else? All I'm saying is we should look at these numbers and I bet that this kind of thing is going on at cities all across the country. If you look at high performing charters, at the middle or high school level. If you look at selective admission schools. I think you're going to find a gender gap there as well.

Robert: Hey, wait a minute. Answer the question. Do you think there should be affirmative action for boys?

Mike: There already is affirmative action at the college level. We know that there are colleges out there that have lower requirements for SAT scores and GPA's for boys than for girls, because, of this problem. Look, I think a little nudging in that direction maybe you could justify, but I'll admit I'm torn on that one. Okay, go ahead Clara, topic number two.

Clara: Writing for The 74, Connor Williams criticized his fellow liberals for defending neighborhood attendance boundaries which keep poor and minority kids out of many good public schools. Does he have a point?

Mike: Robert, you've been gushing all over Twitter on this one.

Robert: Yeah.

Mike: It looks like you're sending a big smackaroo there to Connor.

Robert: I have a man crush on Connor Williams.

Mike: Hey, he's a good looking guy.

Robert: He is.

Mike: He speaks Spanish.

Robert: Does he?

Mike: He covers ELL stuff which frankly nobody else that we know knows. I don't know anything about this stuff.

Robert: I've never seen him in, who's the actor who plays in How I Met Your Mother?

Mike: Uh, I don't know.

Robert: I'm never seen the two of them in the same place at the same time. I think it's . . .

Mike: Oh interesting. I've even seen him Tweet in Spanish.

Robert: Have you?

Mike: How impressive is that?

Robert: He's a smart guy. He's an impressive guy. Does he have a point? If by point, you mean a point of a flaming arrow, then boy what a point. Did you read the piece?

Mike: Yes.

Robert: It's extraordinary. Look, first of all I've got a bias. I kind of love when those of us in this world and ed reform call out members of our own tribe. Some of the best writing and thinking I think comes from this. His piece on The 74, a shout out Campbell Brown 74, this is a terrific piece, points out his fellow liberals for basically getting in the way of choice in neighborhoods like D.C. and he uses D.C. as an example. Where every good liberal says, oh yeah, we're all about inequality, but not when it pertains to my neighborhood school, because, that affects my property value. You have lots of excuses.

Mike: It affects my own kids, right.

Robert: In other words I bought a house in the attendance zone and only kids that are in this attendance zone should be allowed in, or if we allow those "out boundary kids" in it should be a very small, small manageable percentage. There's this piece, or a section of the piece. I just want to quote this, because, it's just so wonderful. He says, "When I confront my fellow liberals about defending the deeply hierarchical inequitable link between real estate prices and school enrollment, they almost always say something like well why can't we just make all schools great?" Which is, he rightly says absurd and it's a homily. It's just not effective.

Mike: All right, but now Robert.

Robert: Let's get personal here.

Mike: Right.

Mike: You send your daughter to a fancy private school in New York.

Robert: I do.

Mike: I moved to Bethesda, Maryland. People who have read my book know about this. This is in the section called selling out of my book from the more diverse Tacoma Park to Bethesda where my son now goes to what I've called a private public school. It's a public school in the same way as a neighborhood swimming is public, it's public for the people that live in that neighborhood. You've just got to make a lot of money to buy into that neighborhood. Look, right, we've got to be careful here to not cast the first stone. I would argue that it is totally understandable that parents want to provide a great school for their kids and are understandably nervous about what may happen if their kids are going to school with lots of other poor kids and that is not managed well. It is a tricky, it is actually not a, it's not exactly a no-brainer to figure out how to create a great school environment, when you have a school that has both poor kids and rich kids learning right by side.

My book, The Diverse Schools Dilemma goes into this that it absolutely can be done, absolutely should be done, but it's hard. Not every educational bureaucracy can pull it off.

Robert: You know, I've said on this podcast, I've used this line a lot. I've got a complicated relationship with blank, with testing, with standards, with curriculum. I do not have a complicated relationship with choice. I'm in favor of it. Does this make me a hypocrite that I send my daughter to private school, no. Here's my take on this. I chose my kid's school. I want you to choose your kid's school, period, full stop.

Mike: Okay, but here's what I'm getting at. Do you believe there should be neighborhood schools?

Robert: That's a really good question. In other words should there be any school that is exclusively open to only people in that neighborhood?

Mike: Uh-huh and be called a public school.

Robert: Probably not. To answer your question, probably not.

Mike: You do surveys, parents love neighborhood schools. White parents, black parents, Latino parents, rich, poor. Everybody likes this idea of neighborhood parents and in fact in places like San Francisco that have tried to get rid of neighborhood schools, they make it all choice. Parents hate it and the middle class parents end up not using the public schools which is probably not good for anybody.

Robert: In his piece Connor Williams quotes Robbie Gupta, who has another terrific turn of phrase. She says neighborhood schools is almost an Orwellian term. It sounds great and can be great in a perfect world, but history is a history of using neighborhood boundaries to segregate. When we say neighborhood schools, aren't we also saying, hello, segregated schools.

Mike: Right, yeah no, we are. I mean it's the same way that neighborhood swimming pool, the same thing.

Robert: Let me go back to your question. Should there be any neighborhood schools? I don't know Mike. Should there be segregated schools?

Mike: Ah-huh, huh. That was, oh turn the knife there, Robert, turn the knife.

Robert: Okay.

Mike: Yes.

Robert: I'm not too far behind.

Mike: I have advised cities, that if you're going to try to create, work toward school integration, absolutely you should do that, but not at the expense of neighborhood schools. That I think the best of all worlds is a place like D.C., where you have neighborhood public schools for people who want them. You also have charter schools for people who want them and then a growing number of charter schools that are working on being socio-economically and racially diverse. That's the piece that we've got to keep working on.

Robert: Okay topic number three.

Mike: You're tough Robert, you're tough, man.

Clara: Robert, in light of our upcoming Constitution Day, you have been taking a look at mission statements of schools across the country. How much attention have you seen being given to civics education in these statements?

Robert: Not very much and not very surprisingly. Listeners to this podcast know that I can get on my high horse about civics and citizenship. We thought, let's do a fun little exercise. Let's look at the mission statements of our largest school systems. Myself, Kate Stringer and Ellen Alpaugh and others just literally spent some time online downloading and looking at mission statements. Let me ask you this, what percentage of America, the top 100 school systems mentioned civics or citizenship at all in their mission statements?

Mike: I hope all of them.

Robert: You would hope, right? Because, that's a founding purpose of public education. Less than half. I think 42 mentioned it. What's really interesting is you see terms like global citizens. There was only one school system, I want to say it was Anne Arundel in Maryland.

Mike: Anne Arundel.

Robert: Thank you. That mentioned . . .

Mike: If you were a paying citizen Robert, you would be better at that. I think it's probably a French skirmish.

Robert: The long story short is that alas not surprisingly very few mission statements among our top school systems mentioned civics and citizenship at all. As I fear they tend to emphasize the private dimension of education. College and career, not civics and citizenship. I'm not saying we should favor one over the other, they should both be there. What's interesting, because let's be realistic, as a teacher I couldn't have told you what the New York City Public School System's mission statement was.

Mike: To employ a hell of a lot of people.

Robert: 80,000 AFT members. Sure, you can't draw a cause and affect line, but it does say something, when the people who we elect as school board members sit down to say, okay what are we all about? That means something. What they're not talking about is this public dimension of education.

Mike: Fascinating. By the way it is going to be Constitution Day on Friday.

Robert: Thursday, right the 17th?

Mike: Right, Thursday, I'm getting my days mixed up.

Robert: Thursday, why civics question Mike, why September 17th?

Mike: That was when the Constitution was ratified.

Robert: Bravo.

Mike: I forget which state was it that put it over. That put it over the top there, I can't remember. Do you remember which one it is?

Robert: I do not.

Mike: Delaware was the first one to . . .

Robert: I'm not that old Mike.

Mike: The first one to sign the Constitution, to ratify, because, of course Delaware was like oh my God, this is an amazing deal. We have a 1000 people in the whole state. We're about the size of a postage stamp and we get two senators, hell yeah. Sign us up for that one.

Robert: They said and we can put it on our license plate.

Mike: Yes, exactly. You know what surprises me as I've thought about this Constitution Day, is I'm surprised it hasn't generated more controversy in the way that Columbus Day has. I suspect that somebody is going to make, here's the issue. You're going to say huh? Our Constitution. How do you celebrate the Constitution Robert? This is a document that had slavery written through and through it. How could we possibly celebrate this?

Robert: There's that thing about building a more perfect Union, Mike. It's not about the destination, it's about the journey.

Mike: I just expect when this piece of yours comes out Robert, you're going to hear from some readers. That how dare you? How dare you talk about this being something that we should celebrate?

Robert: Oh, we'll see. I'll take that challenge.

Mike: I guess what you could point out is that the Constitution now involves all of the amendments including that all so important XIIIth one, not to mention the XIV and the XV, that's your response.

Robert: That is my response.

Mike: That is all the time we've got for Pardon the Gadfly. Now it's time for everyone's favorite, Amber's Research Minute. (Music playing). Amber, welcome back to the show.

Amber: Thank you Mike.

Mike: What happened to your Redskins?

Amber: Isn't it terrible. I know. I was getting excited. Honestly, I'm liking Cousins, but he struggled a little bit, but hey, I mean we did okay. It was a good team we played.

Mike: Amber, change the name.

Amber: (Laughing). You think that's giving us bad karma or something?

Mike: Yes, I do.

Amber: Oh please.

Mike: You don't mess around with the Native American spirits, come on.

Amber: We're not even going to go there. Do you know how many Native Americans like the name? That doesn't get out in the press though, does it? No, it doesn't.

Mike: All right, what you got for us?

Amber: We got a new study out by Marty West and colleagues, that examines the impact of Florida's test based retention policy. I think a lot of people know Florida as of 2003, required that schools retain third graders who failed to demonstrate proficiency on the state reading test and other states you know have followed suit with this third grade reading guarantee.

Mike: Big part of the Florida model that Jeb Bush has promoted for a decade.

Amber: Yes and Ohio does it now too, right?

Mike: Yes, indeed.

Amber: I'm going to forget the other states, but anyway, there are a handful. Analysts are able to conduct a rigorous study that it compares the results from students who are just above and below the cutoff for retention, what's that called, Mike?

Mike: Discontinuity.

Amber: Regression discontinuity.

Mike: Yes.

Amber: Baby, yeah. Looking at within ten test score points. The first cohort to be impacted by the new policy in her third grade in 2002, their track through high school graduation time. They also tracked five additional cohorts, the last of which entered third grade in 2008. Okay, this is descriptive finding.

Mike: By the way, are we sure that all these kids that missed the cut actually got held back? I thought that there was some wiggle room.

Amber: There's some wiggle room, but it's just a special population. It's some loopholes for Sp Ed kids. I do believe there are out of, I do believe they're not in the sample.

Mike: They knew that if a kid, not only missed the cut score, but they were held back.

Amber: Yes.

Mike: They were able to see that.

Amber: They were able to see that.

Mike: Okay.

Amber: All right, they found that the policy increased the number of third graders retained, obviously. It started as, this is interesting it started as 4800 kids prior to the policy introduction. The very next year, just take a guess, how many do you think it jumped?

Mike: 50,000.

Amber: No, 22, 22,000, but still that's pretty big. 4800 to 22,000 in one year. The numbers retained have fallen steadily since then over time as more and more students have cleared the hurdle. Their key finding though is that third grade retention, substantially improves students reading and math achievement in the short run. Okay, that's the important little clause there. Specifically, reading achievement improves for retained students by 23% of a standard deviation after one year. By as much as 47% of a standard deviation after two years, when they are compared to students of the same age, the comparable numbers for math are about 30% of the standard deviation after one year and 36% after three. Yet, the results are short lived like I said, the effects of third grade retention on reading achievement are reduced in years three and four. They become statistically insignificant in years five and six.

Mike: They fade out.

Amber: They fade out. They fade out also in math after six years.

Mike: Okay.

Amber: Okay, all right a little bit more. They also examined results for students in the same grade versus the same age. Those impacts are also positive and persistent through middle school, but you've got to remember that those estimates also capture the effects of being a year older and receiving another year of schooling. Okay, so it's kind of convoluted there. They also find that retention reduces the probability that students at the cutoff will repeat a grade in the future. It doesn't really happen again. Finally, there's a lot of stuff here. Sorry, I know I'm at two minutes now, but finally, they are able to examine graduation impacts for the first cohort. They find that retention has no impact on the probability of graduating from high school, so there's a lot there.

Mike: That actually could be seen as a positive. Some people would worry that if you retain kids, it would increase their chances of not graduating.

Amber: That's right.

Mike: The fact that it's a wash.

Amber: It's a wash.

Mike: You could argue that either way.

Amber: You could, you could. That's what I say, my very next line on my piece of paper. It's a mixed bag.

Mike: Yeah.

Amber: It's a mixed bag. I hate, hate, hate when studies say that and when I say that, but honestly there's some good here.

Mike: Amber, that's what life is about.

Amber: I know.

Mike: It's a mixed bag.

Amber: It's a mixed bag.

Mike: There are trade-offs.

Amber: There's no harm here. We're not really seeing any harm.

Mike: Yeah.

Amber: Okay, but anyway I thought this was interesting. At the end they raised the question, because, just, because, it's a wash, just, because, it's short term impact, it doesn't necessarily mean there couldn't be a long term impact. There have been some studies around early childhood, specially that found no short term impacts, but when they started looking at long term impacts, like college enrollment and earnings, they did find some stuff there.

Mike: The academic achievement might fade out, but maybe this other stuff does not.

Amber: Right, so they say at the end, it's kind of like ooh, ooh, ooh, they say at the end, might find some stuff in Florida, which leads me to believe Marty and his buddies are going to go back to Florida when they've got so more years behind them and check out these other long term outcomes.

Mike: Absolutely, because, it Florida you can follow these kids all the way into college and even into the labor market.

Amber: You can.

Mike: I love it, so we will have to look forward to that.

Amber: We will, but hey it was a great study. It was just really rich you know.

Mike: One last question, there's always been this debate in Florida where of course we have this particular former governor of Florida, who happens to be running for president.

Amber: Happens to be.

Mike: Claiming that on his watch test scores went way up, especially at the fourth grade level, especially for Latinos, low income kids. Some people have asked, is that real? You look at the NAEP and the NAEP scores are very impressive during his tenure. Huge improvement, but somehow was that because of this retention. Was it sort of unfair? That you basically had kids in the sample who had had an extra year of school?

Amber: Yes and they actually did. I didn't fit it in my research minute, which was two minutes. They did look at impact on some populations and they found very few systematic differences. It was basically a wash there as well.

Mike: That would not explain the NAEP difference?

Amber: That's exactly right. They did look at sub pops though.

Mike: There you have it. See people covering the presidential campaigns. There you have it.

Amber: Need to read NBER studies.

Mike: Yes, absolutely. All right, thank you Amber. Brilliant stuff. That is all the time we've got for this week. Don't forget to celebrate Constitution Day on Thursday. Until next week . . .

Robert: I'm Robert Pondiscio.

Mike: I'm Mike Petrilli at the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, signing off. (Music playing).

A new report by the Fiscal Research Center at Georgia State University seeks to quantify how much families were willing to pay for a greater likelihood of receiving access to a charter school between the years 2004 and 2013.

Author Carlianne Patrick examines thirteen metro Atlanta start-up and conversion charter schools that have priority admission zones within their designated attendance zones. Each school has three “priority zones.” The rules governing when a priority zone comes into play and how it interacts with the lottery are quite complex, but the idea is basically this: You get a higher chance of getting into a particular charter school if you reside in priority zone one.

Patrick limits the analysis to home sales within close proximity of the border between priority-one and priority-two attendance zones because they represent a change in admission probability. She claims that residences close to the border—in this case, less than half a mile—should be similar in both observable and unobservable ways, including access to jobs and amenities, styles of houses, foreclosures in the area, etc.

Patrick measures the effect of being on the priority-one side of the border between zones one and two. She also controls for transaction date, which helps with housing value fluctuations over time and limits the sample to “arm’s-length,” single-family residential transactions.

Her key finding is that households are willing to pay a 7–13 percent premium to live in zone one instead of zone two.

The analysis, however, has some flaws. For starters, the sample is very small, and important information is missing. Patrick says nothing about the quality of the schools, the relative difference in the probability of gaining admission between zones one and two, or how familiar parents are with the rules surrounding the zones. She also provides little information on which schools have had to make use of the zone preference and how often they may have done so. Unfortunately, there is no methods appendix to hunt for these answers.

In the end, more evidence is needed to be confident that the zone comparison takes care of other possible unobservable variables. But this is a creative analysis and a cool way to measure how the public may value charter schools. Here’s hoping Caroline Patrick dives deeper in a follow-up study.

SOURCE: Carlianne Patrick, "Willing to Pay: Charter Schools’ Impact on Georgia Property Values," Fiscal Research Center, Georgia State University (August 2015).

The possible existence of a gender bias in the classroom is not a new controversy. Research has shown that, consciously or not, some teachers treat students differently according to gender; they may give boys more (or different types of) attention, encourage boys more in certain subjects and girls in others, and otherwise interact with each gender differently.

Economists Victor Lavy and Edith Sand bring us an important continuation of that work with a National Bureau of Economic Research paper that explores whether students are exposed to gender bias during elementary school. It then examines whether that exposure has an impact on students’ later academic achievement.

Their study follows approximately three thousand elementary school students and eighty teachers from twenty-five different elementary schools in Israel. They first ask: Is there gender bias? In other words, do teachers believe one gender is academically stronger than the other when there’s actually no difference (or even if the preferred gender is actually doing worse)? The answer to this question is yes. By comparing a teacher’s assessment of a student’s performance in a variety of subjects to the student’s scores on external exams in the same subject, the researchers find that girls outscore boys on external math exams, but boys outscore girls on teachers’ own math tests. The researchers find similar results at the classroom level. (In English, girls are over-assessed relative to boys, but the difference is not statistically significant; in Hebrew, the researchers found no signs of bias at all.)

Second, the authors estimate the impact of that math gender bias. The findings are stark—the more positive bias a male student received in elementary school, the higher his eighth-grade test scores; the more negative bias a female student received, the lower her scores. And the effects persist throughout high school. Positive bias for male students increased the likelihood of graduation; negative bias for female students decreased it. The same goes for secondary test scores, the likelihood of a given student enrolling in advanced science and math courses, and even postsecondary enrollment, attainment, and wages. (Two important notes: There were a lot of insignificant results amidst the significant ones, and the effects of a biased classroom seem to be much more important than the effects of a biased student-teacher interaction.)

These are weighty (and troubling) results. A student’s exposure to bias in elementary school can have a lasting effect on not just that student, but ultimately the labor market and economy. Male students are not only on the positive receiving end of bias in math, but are also more likely to “shake off” negative bias, while female students tend to internalize negative feedback.

Interestingly, while the researchers found that older single teachers are more likely to favor boys, they did not report the impact of teachers’ respective genders on bias. This last point would be a particularly interesting line of analysis. As a female math teacher, I was very aware of gender bias against girls in math and science and went out of my way to consciously avoid it. (But would an analysis of my behavior actually show overcompensation and a negative bias toward my male students? Given that my male students had probably experienced positive bias in previous classes, would it have mattered?)

The researchers found classroom effects especially significant—perhaps teacher training programs should explicitly include gender in their courses on teaching in diverse classrooms. My own training for secondary math included instruction on teaching students of different ethnicities, language skills, and cognitive abilities…but never different genders. Clearly, it should have.

SOURCE: Victor Lavy and Edith Sand, “On The Origins of Gender Human Capital Gaps: Short and Long Term Consequences of Teachers' Stereotypical Biases,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper 21393 (January 2015).

This report examines the impact of the Gates Foundation “collaboration grants” in seven cities: Boston, Denver, Hartford, New Orleans, New York, Philadelphia, and Spring Branch (Texas). In each of these cities, districts and charters have signed a “compact” committing them to closer cooperation (and making them eligible for grants). These compacts have many goals, including the increased sharing of facilities, the creation of common enrollment systems, and other changes in policy; however, this report focuses on activities that “target specific staff participants,” such as school partnerships, cross-sector training, and professional development.

Based on conversations with teachers, principals, and central office administrators, the authors conclude that “overall progress in increasing collaboration has been limited.” In particular, while collaboration between principals has increased as a result of the grants, it is still concentrated among those already “predisposed to cross-sector work.” Moreover, in schools not led by such principals, collaboration between teachers is still “minimal to nonexistent.” More progress is evident at the central office level; but even there, some administrators are skeptical that these efforts can lead to “systematic change.” According to respondents, barriers to collaboration include “limited resources, teachers’ unions, and cross-sector tensions.” However, the report also identifies a few promising strategies, including “purposeful” co-location and cross-sector residency programs for aspiring principals.

According to the authors, “the theory of action driving the collaboration grants is that strategic collaboration will advance innovative strategies and practices and promote the transfer and spread of knowledge and effective practice across schools, ultimately resulting in increased school effectiveness.”

This theory can be questioned. After all, since teacher and principal quality are as likely to vary within the district and charter sectors as between them, the notion that sharing “best practices” across sectors is a cost-efficient way to improve outcomes rests on the assumption that the sectors have something to learn from one another that they cannot easily learn from their own high-performers.

Perhaps they do. According to the authors, the practices that district schools were most likely to share with charters were different from those that charters were most likely to share with district schools. Specifically, district schools were most likely to share practices related to ELA and disability instruction, community and family engagement, small group instruction, and guided reading; charters, on the other hand, were most likely to share practices related to culture and behavior, teacher coaching, interim assessment, and strategic data use.

These lists are suggestive of the relative strengths of each sector. Unfortunately, many respondents felt that the goals of the specific collaboration activities in which they took part were fuzzy. Such is the gap between theory and reality.

SOURCE: Moira McCullough, Luke Heinkel, Betsy Keating, “District-Charter Collaboration Grant Implementation: Findings from Interviews and Site Visits,” Mathematica (August 2015).