Where education reform goes from here

(This is a long-form article that we've hosted on an external website. Read it here.)

(This is a long-form article that we've hosted on an external website. Read it here.)

(This is a long-form article that we've hosted on an external website. Read it here.)

There has been much debate in education policy circles of late about whether it’s appropriate for states and charter authorizers to base school-accountability actions solely upon the performance ratings derived from states’ ESSA accountability frameworks.

We—and our organization—strongly favor the framework-based approach. States should take care, however, to ensure that their frameworks accurately measure the performance of all types of schools. Research recently conducted at Pearson indicates that accountability framework gauges can be inaccurate when applied to schools with high levels of student mobility.

How come? It’s due to the well documented "school switching" phenomenon. When students move to new schools, they often experience a one- to three-year dip in academic achievement simply because of the school change.

That’s why studies of school choice programs tend to show short-term performance declines, then positive effects starting around the third year. It takes a while to overcome the negative academic impact that is often caused by switching to a different school. Data from the Connections Academy virtual schools supported by Pearson confirm this effect: Student performance on state assessments improves with each successive year after the student enrolls.

It's not hard to see why the school-switching effect distorts accountability framework measures for schools with much pupil mobility. If a large proportion of a school’s students are new, and therefore can be expected to have scanty or even negative academic growth in a given year, arising from the simple fact that they’re in their first year in that school, this will distort proficiency rates and have an even greater effect on measures of academic growth.

That’s almost certainly part of the reason that virtual schools receive low ratings on many state frameworks. In any given year in the Connections Academy network of virtual schools, for example, 55 percent of students are in their first year of enrollment. State gauges show mobility at traditional schools to be less than half this level.

The most oft-cited research on virtual school performance is the 2015 CREDO study, which compared the academic growth of students in virtual schools to that of their “matched twins” in traditional brick-and-mortar settings. If the Connections Academy data are representative, more than half the virtual school students in the CREDO sample were likely first-year pupils. It is hardly surprising that CREDO’s results showed far lower growth for the virtual students compared to their “matched twins.”

CREDO acknowledged that its study did not include mobility as a matching criterion because the relevant data were not available. (Their matched twins did have similar levels of prior mobility, which is not the same thing.)

Why do virtual schools have such high student mobility? As the Pearson research cited above shows, such schools are often used by parents and students to address specific short-term problems, such as medical challenges and bullying issues, which can only be met with a home-based, flexible learning environment. Add to this the fact that, as long as the virtual sector is growing, it will continue have a higher percentage of new students.

Since pretty much all of the states’ new ESSA accountability frameworks include measures of academic growth, every school with high student mobility is likely to receive an artificially low rating due to the school switching effect. This will not be limited to virtual schools. Large urban districts often have much pupil mobility, too, so the school switching effect will depress their ESSA framework ratings as well.

As part of Pearson’s long-term commitment to understanding the efficacy of its products and services, we analyzed the performance of Connections Academy schools compared to traditional schools, and we used mobility as one of the matching criteria. We found that, once mobility is factored in appropriately, Connections Academy students perform the same as brick-and-mortar students.

The research is available at Pearson’s Efficacy web site. Yes, our organization has an obvious interest in virtual schools, but this study’s conclusions were peer reviewed by SRI International, and the validity of the data was verified by PriceWaterhouseCooper. We are happy to provide the technical notes to anyone interested.

The implication is not that framework-based accountability is invalid or that framework ratings should be dismissed. Rather, it is that accountability systems must take student mobility into account if they’re to accurately measure school performance and school effectiveness. There are a variety of ways to do this.

For example, frameworks should report proficiency and growth for all students, and also include separate proficiency and growth metrics for students who are in their second year, as well as separate data for students in their third year and beyond. This would help isolate the school’s performance from the effect of mobility, which it cannot control.

Frameworks should also look at high school graduation rates differently. At the very least, they should adopt the Fordham proposal of allocating students to school cohorts based on the percentage of their high school years spent in a given school.

The framework score should be thought of as analogous to an X-ray. If it shows a potential problem, there should be further diagnostics—the equivalent of a CT scan to see if the X-ray might be giving a false signal due to student mobility.

If further analysis shows that the school does indeed have a high level of student mobility, then it is time for the MRI: Other data should be analyzed to confirm or dismiss what the framework showed. What are the growth and proficiency rates of second- and third-year students? What is the annual rate of credit accumulation for high school students? These and other data should be analyzed to answer the question: How do the students perform during the time they are actually enrolled in the school?

If these analyses still show that school is in distress, then accountability actions would be warranted. But if they reveal that low scores are in significant part artifacts of high mobility, then that needs to be considered by regulators. The framework should be the starting point, not the final word. Framework measures should not be used as automatic triggers for accountability actions.

This new research provides solid evidence of the need to factor student mobility into accountability systems. This can be done through careful construction of the data that go into the framework, and through additional analysis after the raw framework score has been determined.

We hope that this analysis advances the understanding of student mobility, and its effect on measures of student and school performance. We also hope that it illustrates why raw framework scores should not be the sole basis for school accountability actions.

The views expressed herein represent the opinions of the author and not necessarily the Thomas B. Fordham Institute.

If you’re looking for ideas about the future of the education system, there is no shortage on YouTube, where scholars and charlatans alike seek to redpill you with ideas of often dubious merit. Brilliant ones really do exist, though, and my personal favorite is by the former dean of the University of Oklahoma Honors College, David Ray. (Full disclosure: I attended the University of Oklahoma for a couple of years and had a class with Dr. Ray, although they would have never let me near the Honors College.)

Dr. Ray’s lecture raises important questions about the value of education, the structural changes happening in the economy, recent social and cultural trends, and how these all interact. His concluding thoughts are refreshingly unsatisfying, and at the beginning of the talk he warns the audience, “You will be annoyed.” Bare of the hubris of the typical self-proclaimed “thought leader,” Dr. Ray’s TedTalk offers a lot of wisdom, but it is what he says about education technology and student motivation that I keep going back to.

Dr. Ray reflects frankly on his nearly forty years of experience teaching undergraduates with a range of motivation, and his take on the importance of student motivation is a minor but consequential part of a talk. Citing the book Academically Adrift, he points out that students admit to studying much less than they did a few decades ago. This withering appetite for knowledge is reflected in Dr. Ray’s own syllabuses: Whereas in the past he would assign nine books for a course, today’s students expect a single textbook accompanied by lectures that “talk about the book,” as if there should be no expectation that students have done their readings prior to class. Though many students may be working hard at other things—taking multiple jobs to support families or to pay for ever higher tuition—Dr. Ray argues convincingly that students are working much less on their studies than in the past. Of course some students are highly motivated and still put in the academic work necessary for a real education. “These students are terrific,” Dr. Ray says, “but they are a minority.”

Dr. Ray points out that his university has “a required freshman comp sequence, an aggressive expository writing program, two different writing centers, and several professional colleges—architecture, management, and engineering—that have added a writing course,” yet many still graduate unable to write well. For many students, the problem is not lack of access, but lack of uptake.

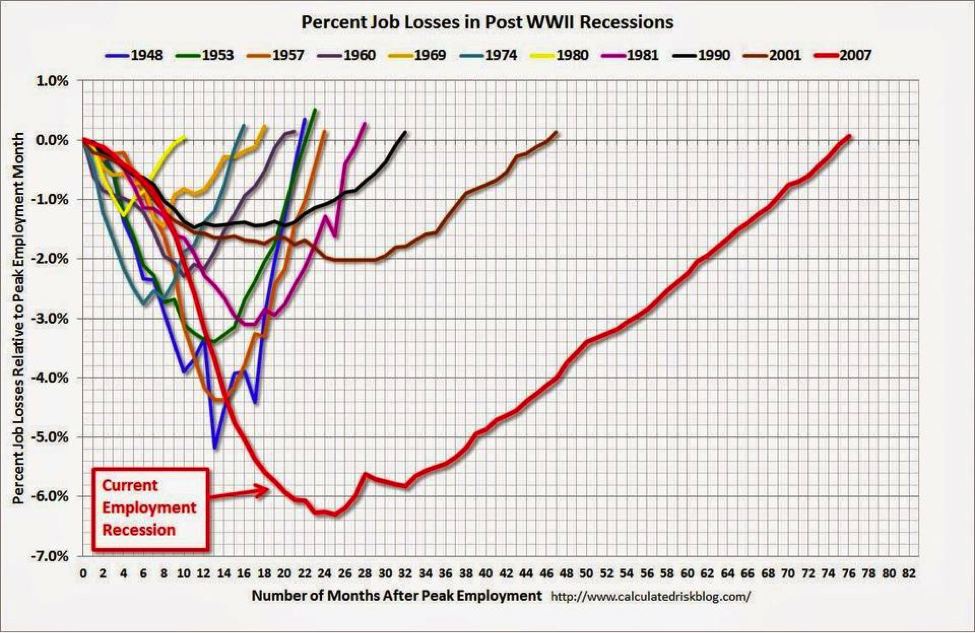

Looming over Dr. Ray’s argument are the macroeconomic trends that he believes are shaping higher education and the job market students face after graduation. The figure reproduced below is, according to Dr. Ray, “the single most important graph I’ve ever seen.” It shows that more recent economic recoveries (represented by the black, brown, and red lines) have been very slow and largely “jobless.” When Dr. Ray’s gave his lecture in 2014, the U.S. still hadn’t recovered the jobs that were lost in the Great Recession, which began almost five and a half years earlier. Slower recoveries mean not only pain for workers—whether they have a credential or not—but also shrunken budgets for things like education.

In this bleak economic context, a college degree seems even more necessary to many families. But with fewer resources to devote to education, they are having a hard time paying tuition, and student debt has grown dramatically. “In the best American way,” Dr. Ray offers, “we look to technology as a way to be more efficient.” The catch, however, is that, without student motivation, technology helps only so much.

In this bleak economic context, a college degree seems even more necessary to many families. But with fewer resources to devote to education, they are having a hard time paying tuition, and student debt has grown dramatically. “In the best American way,” Dr. Ray offers, “we look to technology as a way to be more efficient.” The catch, however, is that, without student motivation, technology helps only so much.

The incredible technologies of the twenty-first century have made humanity’s knowledge base available to almost everyone, and tools that have been created just in the past few years—massive open online courses (MOOCs), YouTube tutorials, online coding modules, and others—have made many aspects of an education free and accessible to anyone with a smartphone or a library card. Dr. Ray extols the promise of education platforms that can reach millions of students at zero cost to the student, such as Khan Academy and the MOOC. Yet, he admits that the latter “actually didn’t work very well. It worked fairly well for some students, the motivated students. But the unmotivated students didn’t finish.”

He suggests that, eventually, “market realities”—and here he points at the graph—“will motivate [students], usually after the fact and very harshly.” But will they? For a student, market realities can seem very far off, and this is especially true for middle school and high school students who must build the foundational skills that prepare them to be successful in college. Once these opportunities have been missed or someone is out of school, catching up can be costly and, for adults, disruptive to family and career. A reason our country continues to experience poor educational outcomes is precisely that distant market realities aren’t enough to motivate students, who may never acquire the skills and knowledge needed for a successful, independent adulthood.

Yet an implication of Dr. Ray’s observations about student motivation and the potential of ed tech is that more motivated students will take better advantage of new technologies and educational opportunities. Inspired by Dr. Ray’s lecture, I have been researching student motivation for the past few years, and in a recent article in Education Next, my colleague Mike Petrilli and I present some of our takeaways from this research. In the article, we argue that education policy must help bridge the gap between student effort and reward, motivating our young people to invest in themselves early on. And we present evidence that better educational policies can be used to spur student motivation, and get students to contribute more effort. More work on this issue needs to be done, but our hope is that, with the plentiful educational resources of our internet age, better motivated students will zoom ahead farther than we could have imagined.

On this week’s podcast, David Griffith, Adam Tyner, and Brandon Wright discuss New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio’s plan to revamp the admissions process for the city’s selective high schools. On the Research Minute, Amber Northern examines why ELL kids are doing better than we think on NAEP.

Michael J. Kieffer and Karen D. Thompson, “Hidden Progress of Multilingual Students on NAEP,” Educational Researcher (June 2018).

A-to-F school rating systems have come under fire in Ohio and remain a hotly debated topic elsewhere. Proponents usually argue that they provide clear information that parents and communities can easily digest, while also motivating schools to improve. Critics often claim that such blunt ratings could damage schools’ reputations or demoralize educators should they receive poor grades. But what does the research have to say?

A recent study by Rebecca Dizon-Ross examines the impacts of A–F school accountability in New York City (NYC) on teacher turnover and quality, as estimated by value added measures. Under the leadership of former mayor Michael Bloomberg and school chancellor Joel Klein, NYC began in fall 2007 to assign A–F school grades and link low ratings to consequences. Prior research has already shown that these accountability reforms led to higher student achievement, with gains concentrated among children attending low-rated schools. Dizon-Ross studies teacher workforce patterns in 2008–09 and 2009–10 and uses a regression discontinuity design that focuses on schools near letter grade cutoffs to gauge the effects of receiving lower accountability ratings.

The analysis finds that NYC’s policy reforms reduced teacher turnover and likely increased teacher quality among the city’s lowest rated schools. Schools barely falling into the F (versus D) and D (versus C) categories had turnover rates that were 3 percentage points lower than schools on the other side of the cutoffs. Dizon-Ross calls this reduction a “large effect,” considering that turnover rates are typically 10 to 20 percent in NYC schools. Meanwhile, the teacher quality findings are deemed only “suggestive evidence” due to the small number of teachers with value added scores. Nevertheless, the analysis uncovers quality improvements among teachers who joined lower-rated schools. Since there were no effects on the quality of teachers who left those schools, the result is a net positive impact on quality. The positive findings apply to schools at the bottom of the rating distribution—where the accountability “bite” is strongest—with null results generally found among schools at the top (A or B).

Why would teachers want to work at lower-rated schools? To answer this question, Dizon-Ross examines teacher survey responses that cover a range of issues, including school leadership, professional development, and parental engagement. Based on an analysis of these data, she concludes that strong, supportive principals drove reductions in turnover and higher teacher quality. She writes, “this [analysis] suggests that low grades encouraged principals to work harder at their jobs and that teachers appreciated these changes.”

Despite the outcries around A–F ratings that carry consequences for poor performance, research from NYC and Florida show that such systems benefit students. Now this study indicates that accountability pressures can improve working conditions by incentivizing principals to put more effort into employee retention and recruitment. Given these empirical findings, it’s worth asking: What’s not to like about school accountability?

SOURCE: Rebecca Dizon-Ross, How Does School Accountability Affect Teachers? Evidence from New York City, National Bureau of Economic Research (2018).

Since 2012, Tennessee has taken a unique approach to intervening in struggling schools. With the goal of turning around the lowest-performing 5 percent of schools in the state (known as priority schools), officials introduced two separate models: the Achievement School District (ASD) and Innovation Zones (iZones). The ASD is a state-run district that directly manages some priority schools and turns others over to select charter management organizations. iZones, on the other hand, are subsets of priority schools that remain under district control but are granted greater autonomy and financial support to implement interventions. There are four districts that contain iZones: Shelby County Schools (Memphis), Metro-Nashville Public Schools, Hamilton County Schools (Chattanooga), and Knox County Schools (Knoxville). The remaining priority schools weren’t included in either of these initiatives, effectively creating a comparison group.

Research teams from Vanderbilt University and the University of Kentucky have kept a close eye on both initiatives. In 2015, they published an evaluation of the ASD and iZone schools after three years of implementation. They found that, while ASD schools did not improve any more or less than other priority schools, iZone schools produced moderate to large positive effects on student test scores. A separate study also found that both initiatives had high rates of teacher turnover, but that the numbers were higher in ASD than iZone schools.

Now a recently published study examines the impacts of both initiatives after five years of implementation. To complete their evaluation, the researchers examined student- and teacher-level demographic data, test scores on state assessments, and school enrollment data from 2006—07 through 2016—17. They then compared changes in test scores after reforms were initiated with changes in test scores in priority schools that weren’t part of the ASD or iZones.

The five-year findings are similar to the results of the three-year evaluation. After five years, iZone schools showed moderate to large positive and statistically significant effects on reading, math, and science test scores. These results that suggest iZone schools were able to sustain their early success. ASD schools, on the other hand, showed insignificant results across all three subjects—that is, they did not gain more or less than non-ASD or iZone priority schools. Since the ASD includes recent cohorts of schools that were only exposed to one to three years of reform, the researchers also reviewed the data using only the first two cohorts of schools, those overseen by the ASD for four or five years. However, they found that effects were still not statistically significant in any subject.

The researchers also took their analysis a step further by comparing the iZone’s positive results to other turnaround results across the country. They found that, in reading, iZone gains of 0.14 standard deviations were similar to those that occurred under the School Redesign Grants model in Massachusetts and the state takeover of Lawrence Public Schools. In math, iZone effects ranging between 0.16 and 0.20 standard deviations were similar to gains achieved in Philadelphia’s restructured schools.

Overall the results for ASD schools were disappointing, but the findings of this brief and the gains made by iZone schools are a valuable addition to existing school turnaround research.

SOURCE: Lam Pham, Gary T. Henry, Ron Zimmer, Adam Kho, “School Turnaround After Five Years: An Extended Evaluation of Tennessee’s Achievement School District and Local Innovation Zones,” Tennessee Education Research Alliance (June 2018).