Bar Exam for Teachers?

The AFT's new and much-ballyhooed proposal, contained in a report titled Raising the Bar, revives the Shanker-era idea of a “bar exam” for entering teachers

The AFT's new and much-ballyhooed proposal, contained in a report titled Raising the Bar, revives the Shanker-era idea of a “bar exam” for entering teachers

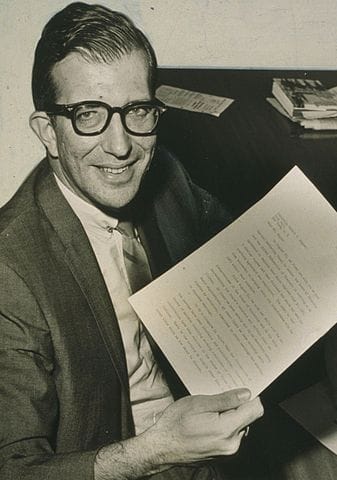

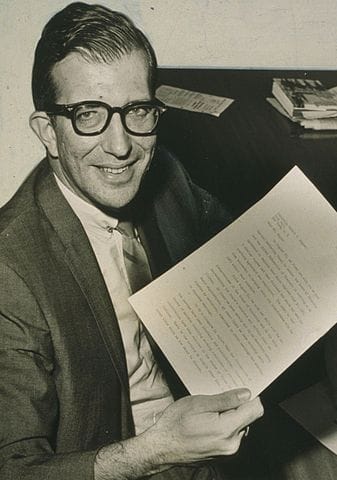

The late AFT president Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the NBPT. Photo from the Library of Congress.. |

As President of the AFT, the late Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) and much else in the education-reform world. Now Randi Weingarten is trying—earnestly and imaginatively—to return the organization and its (present) leader to the pantheon of real reformers.

Their new and much-ballyhooed proposal, contained in a report titled Raising the Bar, revives the Shanker-era idea of a “bar exam” for entering teachers—and charges the NBPTS with putting it into practice.

Andy Rotherham came out within hours with multiple doubts, some of which worry me, too. But let’s start by crediting Ms. Weingarten and her organization with a serious proposal to raise standards for new teachers as part of a broader effort to strengthen the profession.

Their proposal has three pillars. The second—but most important so far as I’m concerned— is this:

Teaching, like other respected professions, must have a universal assessment process for entry that includes rigorous preparation centered on clinical practice as well as theory, an in-depth test of subject and pedagogical knowledge, and a comprehensive teacher performance assessment.

My eye went immediately to the phrase “in-depth test of subject…knowledge,” and I combed the rest of the document seeking more on that topic—only to be dismayed by how little is actually said on the matter, other than that the NBPTS is supposed to figure it out. There is no hint of what in-depth knowledge might mean for a U.S. history teacher versus a geometry teacher versus an art teacher, nor does it address what sort of testing arrangement might gauge whether an individual possesses enough of it. (We know that the current arrangement—with most states relying heavily on the “Praxis II” test—does not do this well. We also know that some states do not take this issue on at all.)

The other two pillars, I have to admit, gave me pause. The first says “all stakeholders must collaborate”—a recipe for stasis and mediocrity if I’ve ever seen one. And the third assigns “primary responsibility for setting and enforcing the standards of the profession” to “members of the profession—practicing professionals in K–12 and higher education.” In other words, elected officials, employers, taxpayers, and parents can jolly well butt out; the standards governing classroom entry are none of their business. (I guess that’s true for think-tankers, too.)

Back to the “universal assessment”: I can easily understand why the AFT is giving that assignment to the NBPTS, but I’m not sure that organization is up to it—particularly the “knowledge” part. They administer very elaborate and expensive appraisals of teaching practice to veteran classroom practitioners, but I’ve never seen the National Board show much interest in subject-matter knowledge. Pedagogy, yes. Even lesson-planning. But not the causes and consequences of the Civil War or the ways that atoms combine to form molecules. Indeed, I’ve seen scant evidence that the powers-that-be at NBPTS even care much about such mundane stuff as content knowledge. (This part of the job, at least for grades K–8, should have been assigned to the Core Knowledge Foundation).

All of which is to say, the devil lurks prominently in details that are yet to be developed, not in the impulse to raise entry standards for teachers. (Unsurprisingly, this union-developed proposal deals only with new teachers, not with whether veteran instructors need to meet any standards of any sort.)

The Rotherham critique includes four more notable points.

Some of these are unanswerable within the framework of the AFT proposal and the NBPTS, the more so once it rounds up “all stakeholders.” But let’s not doom this baby at birth. Let’s welcome its arrival, wish it good health, cross our fingers (maybe even help if asked), and stand by ’til it can walk by itself. Thanks, Randi, for a proposal that would make Al proud—and that could conceivably do American education some good. Or could just as easily create nothing except false hope and, possibly, some damage.

This new study by Brookings’s Matt Chingos makes its way through the labyrinth of state budgets for standardized assessments, and it is the first time we’ve ever seen anything coherent and reasonably comprehensive on this part of the K-12 spending universe. Chingos focuses on the costs of contracts between states and test-making vendors, which comprise about 85 percent of total assessment costs. Across the forty-five states for which data were available, $669 million was spent annually on standardized assessments for grades three through nine. That’s about $27 per pupil on average, but this figure varies widely: A child in D.C. costs $114 to assess; in New York, that same child would cost just $7. Some of the variance is due to state size. He estimates that states with about 100,000 students in grades three-nine (e.g., Maine or Hawaii) spend about $13 more per pupil on assessment than states in the million-pupil range, such as Illinois. From these data, Chingos concludes that all states would enjoy some savings by joining or creating assessment consortia—whether PARCC or SBAC for ELA and math or another smaller grouping for other subjects. Much speculation surrounds the in-development Common Core assessments; the new design is likely to cost more, though it’s difficult to estimate how much at present. (We’ve also weighed in on this topic.) Chingos shows that new (and hopefully better) assessments could be rolled out at about the same cost to states, provided they pool resources and eke out quantity gains.

SOURCE

Mathew M. Chingos, Strength in Numbers: State Spending on K-12 Assessment Systems(Washington, D.C.: Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, November 2012).

Three years ago, Stanford’s Center for Research in Education Outcomes (CREDO) up-ended the conversation on charter school effectiveness with its much-cited study of sixteen states’ charter schools. This new report extends that kind of analysis into the Garden State, where the authors find a bumper crop of quality charters, particularly in Newark. CREDO analysts matched over 10,000 charter students in grades three through eight with “twin” students in traditional public schools (rigorously controlling for a host of student characteristics), tracking them between 2006-07 and 2010-11. The report offers a host of interesting data and solid ammunition for charter proponents in New Jersey—though its findings also raise a few serious questions. First, the good news for charters: Sixty percent of New Jersey charters outpace district learning gains in reading and 70 percent do so in math. And only 11 percent and 13 percent perform significantly worse (for reading and math, respectively). Statewide, charters added about two more months of annual learning in each subject compared to traditional public schools. Newark charters boast an additional seven and nine months’ learning in reading and math over the course of a year, respectively. Large positive effects in math were found for poor students and English language learners in charters, as well as small positive effects for black and Hispanic youngsters. Still, the report reveals shortcomings of charters too (some which—without further explanation—seem incongruous with the findings reported above). Notably, charter students in Jersey’s other four major cities (Camden, Jersey City, Paterson, and Trenton---which, with Newark, comprise the lion’s share of Garden State charters) performed worse in reading than their district peers (and on par in math). The report offers one takeaway: Policies matter—and those in NJ (including strict entry requirements, diligent closings of low-performers, and scaling up quality charters) should be praised, studied, and replicated. Huzzah, New Jersey! And huzzah, Newark!

Three years ago, Stanford’s Center for Research in Education Outcomes (CREDO) up-ended the conversation on charter school effectiveness with its much-cited study of sixteen states’ charter schools. This new report extends that kind of analysis into the Garden State, where the authors find a bumper crop of quality charters, particularly in Newark. CREDO analysts matched over 10,000 charter students in grades three through eight with “twin” students in traditional public schools (rigorously controlling for a host of student characteristics), tracking them between 2006-07 and 2010-11. The report offers a host of interesting data and solid ammunition for charter proponents in New Jersey—though its findings also raise a few serious questions. First, the good news for charters: Sixty percent of New Jersey charters outpace district learning gains in reading and 70 percent do so in math. And only 11 percent and 13 percent perform significantly worse (for reading and math, respectively). Statewide, charters added about two more months of annual learning in each subject compared to traditional public schools. Newark charters boast an additional seven and nine months’ learning in reading and math over the course of a year, respectively. Large positive effects in math were found for poor students and English language learners in charters, as well as small positive effects for black and Hispanic youngsters. Still, the report reveals shortcomings of charters too (some which—without further explanation—seem incongruous with the findings reported above). Notably, charter students in Jersey’s other four major cities (Camden, Jersey City, Paterson, and Trenton---which, with Newark, comprise the lion’s share of Garden State charters) performed worse in reading than their district peers (and on par in math). The report offers one takeaway: Policies matter—and those in NJ (including strict entry requirements, diligent closings of low-performers, and scaling up quality charters) should be praised, studied, and replicated. Huzzah, New Jersey! And huzzah, Newark!

SOURCE

Center for Research in Education Outcomes, Charter School Performance in New Jersey (Stanford, CA: CREDO, November 1, 2012).

A widely-noted Government Accountability Office (GAO) report back in June found that charter schools serve a disproportionately low number of special-education students, feeding concerns that these schools discriminate again special-needs (and ELL) youngsters. This latest from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) adds much-needed nuance and should quell some of the concern. CRPE analysts examined 2011-12 special-education enrollments across 1,500 district and 170 charter schools in New York State, finding that aggregates in that state mask important differences across grade band, location, and authorizer. At the middle and high school levels, New York special-education enrollments are nearly identical in the district and charter sectors, with the only variance—albeit sizable—occurring at the elementary level. (The authors offer a few suggestions as to why, including that charter elementaries are less likely to label students special-needs as they have more effective behavior-management systems, smaller classes, or a general insistence on “individualized” education for every pupil.) From these findings, the researchers draw cautionary policy recommendations, urging against the adoption (or continuation) of blanket special-education-enrollment requirements. (New York has such a law; more on this on our Choice Words blog). Not a bad first step, considering that such requirements often lead to over-identification of students as disabled. But let’s also recall the larger question: Why should a single school—charter or otherwise—be expected to appropriately serve all students?

A widely-noted Government Accountability Office (GAO) report back in June found that charter schools serve a disproportionately low number of special-education students, feeding concerns that these schools discriminate again special-needs (and ELL) youngsters. This latest from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) adds much-needed nuance and should quell some of the concern. CRPE analysts examined 2011-12 special-education enrollments across 1,500 district and 170 charter schools in New York State, finding that aggregates in that state mask important differences across grade band, location, and authorizer. At the middle and high school levels, New York special-education enrollments are nearly identical in the district and charter sectors, with the only variance—albeit sizable—occurring at the elementary level. (The authors offer a few suggestions as to why, including that charter elementaries are less likely to label students special-needs as they have more effective behavior-management systems, smaller classes, or a general insistence on “individualized” education for every pupil.) From these findings, the researchers draw cautionary policy recommendations, urging against the adoption (or continuation) of blanket special-education-enrollment requirements. (New York has such a law; more on this on our Choice Words blog). Not a bad first step, considering that such requirements often lead to over-identification of students as disabled. But let’s also recall the larger question: Why should a single school—charter or otherwise—be expected to appropriately serve all students?

SOURCE

Robin Lake, Betheny Gross, and Patrick Denice, New York State Special Education Enrollment Analysis (Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, November 2012).

Checker and Education Sector’s John Chubb discuss expanding the school day, dismal graduation rates, and Louisiana confusion. Amber depresses us with a report on record-high unemployment among young people.

Youth and Work: Restoring Teen and Young Adult Connections to Opportunity by The Annie E. Casey Foundation - Download PDF

This timely study represents the most comprehensive analysis of American teacher unions' strength ever conducted, ranking all fifty states and the District of Columbia according to the power and influence of their state-level unions. To assess union strength, the Fordham Institute and Education Reform Now examined thirty-seven different variables across five realms:

1) Resources and Membership

2) Involvement in Politics

3) Scope of Bargaining

4) State Policies

5) Perceived Influence

The study analyzed factors ranging from union membership and revenue to state bargaining laws to campaign contributions, and included such measures such as the alignment between specific state policies and traditional union interests and a unique stakeholder survey. The report sorts the fifty-one jurisdictions into five tiers, ranking their teacher unions from strongest to weakest and providing in-depth profiles of each.

A foundation staffer I think well of posed these vexing questions the other day:

With the transition to the new Common Core assessments, states will have a number of decisions around how they use the new tests. Some of the most consequential are around possible use of the tests for high school exit or grade promotion. These are obviously sticky subjects. Should we be scrapping exit exams, especially given that they tend to be 9th-grade level at best anyway? Is there a need for an overall re-thinking and rationalization of state testing in general—rather than piling more on top?

Could Common Core improve the value of a high school education? Photo by Anna Botz |

Here’s what I think:

States today have sharply divergent views of what stakes, if any, to attach to test results for kids. Several have test-based 3rd-grade reading “gates” that you must pass to advance to 4th grade (Jeb Bush said the other day that “Seven states have started on this journey”). A few have “kindergarten-readiness” assessments (though those are more often teacher “checklists” than tests). And the last time I checked, about half the states have statewide exit tests that are prerequisite to graduating from high school, though it’s true that most peg such exams to what are today deemed 9th- or 10th-grade standards. (Under Common Core, I’d wager, a bunch of current state exit tests would correlate more with 7th- or 8th-grade standards!)

Some states also have end-of-course exams in high school, the passing of which is related to getting a diploma, and there’s a widening belief in educator-land that this is a better course of action than a single statewide exit test.

But a lot of states do none of those things because they don’t really believe in high stakes for kids (or can’t get away with it politically, or are totally into “local control”), and they tend to trust teacher judgment when it comes to passing students from grade to grade or awarding the course credits that, when accumulated, yield a diploma.

Remember that even where states require passing an exit exam as a condition of high school graduation, I’m not aware of a single place where the resulting diploma is automatically accepted by colleges as evidence of readiness for credit-bearing courses. Nor am I aware of employers who accept it willy-nilly as evidence of employability, at least not in modern-style jobs—which is to say, exit exams (and end-of-course exams) have currency within the K–12 world, but the real world doesn’t yet give them much credit. On the other hand, nobody has ever claimed (to my knowledge) that passing the state’s exit exam signifies true “college/workforce readiness,” which is what Common Core purports to do. (Passing an AP exam with a high-enough score may yield actual college credit, not just placement in college-level courses.)

Big changes lie ahead, but these are fraught with peril. If the “cut scores” (still to be set by the two assessment-building consortia) on new Common Core assessments at the 12th grade level truly signify college/workforce readiness and are accepted as such by the real world, the failure rate will be enormous for years to come and the political pushback will be powerful. How many states can withstand not giving diplomas to large fractions of kids who have persisted in school through 12th grade? Yet if they continue to give diplomas to just about everyone who persists, then many of those diplomas will continue not to signify college-workforce readiness and the real-world incentive/benefit effect will continue to be lost.

Major league dilemma here! As higher standards gain traction from kindergarten upward and as kids entering, say, 9th grade really have attained the Common Core’s 8th grade standards, this issue may resolve itself. But it will take a decade or more after the new standards are in place (and the new assessments begin to be administered) before this transformation will work its way through the system—if indeed it ever does.

States will want, and probably need, to handle this differently from one another. But a near-immediate dilemma faces the assessment consortia regarding the setting of “cut scores” and definition of proficiency: Will these definitions be uniform for all states using the new assessments or will each state set its own? If the latter, much of the benefit of a “common” standard will be lost. If the former, there’s going to be a huge ruckus within the consortia about how high or low to set those passing scores. (Keep in mind that Alabama and Arkansas, for example, belong to the same consortium as do Maryland and Massachusetts.)

I think three important things should happen—but all will be contentious.

First, the consortia should set more than one “cut score” on their new exams. I don’t mean different state-to-state—I mean uniform but multiple, akin to NAEP, with its “basic,” “proficient,” and “advanced.” But this time, it should be more like “minimal,” “tolerable,” and “truly college/career ready.” This should be done at all grade levels, and kids (and parents and teachers) need to see the steep trajectory if they want to get from, say, minimal in 3rd grade to tolerable in 7th grade and “truly ready” by the end of high school.

Second, states should—for some years, but maybe not forever—award two kinds of high school diplomas: One will resemble the old kind and represents Carnegie units or maybe passing an old-style exit exam (or both), and nobody will claim that it denotes college/career readiness. The new one, however, will correlate with the “truly ready” level on the Common Core assessments (and whatever additional graduation requirements a state may want to impose in other subjects).

Third, to make worthwhile the pain and suffering that kids and teachers and schools will endure to achieve that “truly ready” diploma, it’s got to be useful in the real world. This is to say, a great many colleges must accept it as evidence of readiness for college-level work (at least in math and English), and a bunch of employers must do the equivalent.

Maybe the old-style diploma can be phased out over a decade. Or maybe not. This depends on how desirable or practical one thinks it is to try to get everyone up to college-entrance level by the end of high school. That’s a topic for another day—but I’ve got my doubts. Maybe I’m haunted by NCLB’s pious but feckless declaration that everyone in America would be “proficient” by 2014.

The Louisiana Constitution allows lawmakers greater freedom to design public education than the state’s school boards and teacher unions would have us believe. So it’s no surprise that what is “public” in the Bayou State today includes a largely charter school system in New Orleans, four publicly funded private-school-choice programs, a recovery school district, and online charter schools.

Jindal sought more than just budgetary leftovers when working to fund the voucher program. Photo from Wikimedia Commons |

That’s why it was frustrating to see a state judge declare late Friday that Louisiana’s newest and largest voucher program is illegal because it diverts “vital public dollars” to private schools. According to Judge Timothy Kelley, the state was wrong to fund its new voucher program from the same revenue stream that provides a “minimum foundation” to its public elementary and secondary schools.

That was the same argument put forward by the Louisiana Federation of Teachers and the Louisiana School Boards Association when they sued to abolish the voucher program, which already serves nearly 5,000 children in 113 private schools.

But what is the difference between privately operated charter schools and private schools accepting voucher-bearing students if both kinds are held accountable to parents and taxpayers?

Students receiving the Louisiana voucher have to take the same standardized tests as those administered at public schools, and the schools they attend can be ejected from the program if they consistently show poor performance—just like charter schools. But Judge Kelley clumsily asserts that Louisiana’s charter schools and recovery school district are attempts to manage public schools “by a private entity,” whereas the voucher program illegally diverts public funds “into the hands of nonpublic entities.”

What’s the distinction, one may ask? Very little, and probably nothing important. And that’s why Governor Bobby Jindal led the effort to maximize the state’s constitutional power to create a public education system to enhance every child’s well-being with every available tool. Furthermore, Jindal sought more than just budgetary leftovers and worked to fund the voucher program from the same pot of money that bankrolls nearly all public education in Louisiana.

In rejecting this argument, Judge Kelley even parroted the language of school-choice opponents when he wrote that the voucher program ignored “the good of the individual students who are left behind in those schools deemed underperforming.” Fortunately, the students now in the voucher program can stay there while Jindal appeals the decision. That may be the only good news here. The consolation for the families who opted for school choice is that this was always going to be decided by the Louisiana Supreme Court. It just shouldn’t have been they who had to appeal.

A version of this article appeared in Fordham’s Choice Words blog.

The last thing Detroit families need is for an incompetent school board to regain control of the Motor City’s worst schools, but that may happen now that Michigan voters have repealed the state’s “emergency manager” law. The repeal has emboldened the Detroit Board of Education to undo many of the biggest reforms that emergency managers have put in place in the district during the last four years. Perhaps the worst of these decisions (so far!) was voiding the contract that emergency manager Roy Roberts forged last year with the state’s fledgling Education Achievement Authority, a recovery district modeled on Louisiana’s and run out of Eastern Michigan University. The EAA had taken possession of the lowest-achieving schools in Detroit (and has been praised by Arne Duncan), but it remained an inter-local agreement between the university and the school district. The Detroit school board, which one newspaper columnist said was “sauced on power and staggering with incompetence,” now wants to take those schools back under its fold. Eastern Michigan has vowed to fight, but it’s hard to see how kids will benefit from this custody battle if the state doesn’t codify the recovery district into law. Two bills were introduced recently in the legislature to do just that, but their sponsors have met with critics who maintain that the Achievement Authority needs more time to prove itself. That’s an absurd position, considering the thousands of Detroit families who been waiting for an ounce of hope for years.

RELATED ARTICLE

“Fight over Detroit Education Achievement Authority control comes to head,“by Jennifer Chambers, The Detroit News, November 26, 2012.

Did the LA school district trade their magic beans for a cow? Drawing by George Cruikshank. |

The Los Angeles school district and that city’s teacher union have reached what looks like the lamest compromise since the merchant traded Jack his magic beans for a cow. Sure, they say that teacher evaluations will include student achievement—but they’ve conspicuously left out any details regarding how much of such evaluations those may comprise. (The Los Angeles Times reports that it will be less than 50 percent). What’s more, teachers’ value-added scores will only be included in “feedback” sessions. Will we find out later that LAUSD leaders actually traded the teacher union a handful of pinto beans and received in return a proper cow? Or did they give up the beanstalk?

Twenty-thousand students in five states can expect their school year to increase by 300 hours. This three-year pilot program, which targets low-performing schools, will be funded by a mix of state, federal, and district funds, with the Ford Foundation picking up the slack and the National Center on Time & Learning providing technical assistance. How much of a good thing is this? On the one hand, American kids are spending too little time in school to learn all that they need to—and less than their peers in many high-achieving lands. On the other hand, much of the current school day is spent unproductively. (Bill Bennett once observed that if you’re a lousy chef with a bad omelet recipe, adding another egg to the mix won’t likely produce a more palatable result.) Besides, in an era of technology, who says all worthwhile learning needs to occur under the school roof? Still and all, this pilot is worth piloting—and studying carefully. We’ll be watching closely.

The first-ever federally compiled graduation rates were released last week, revealing lower-than-expected rates in most states and wide racial and socioeconomic achievement gaps. Kudos are due to the Department of Education for creating the common measure. But what happens next? We’ve known for a long while that graduation rates are too low and achievement gaps too wide.

Buzz surrounds outgoing Indiana State Superintendent Tony Bennett’s bid for the post of Florida Education Commissioner. He isn’t the only finalist but he’s by far the strongest candidate—and the powers that be in Florida deserve accolades for making the post worthy of him. Interviews are scheduled for Tuesday and are open to the public. We encourage the selection of our 2011 Ed-Reform Idol.

The Data Quality Campaign issued two reports last week: One details how states’ inability to share data creates knowledge gaps for educators, policymakers, parents, and students, while the other suggests ways to “break down the data silos” between states. Both build upon the DCQ’s laudable previous efforts to shepherd states towards better data systems. Get a move on, states! You know what you must do.

This timely study represents the most comprehensive analysis of American teacher unions' strength ever conducted, ranking all fifty states and the District of Columbia according to the power and influence of their state-level unions. To assess union strength, the Fordham Institute and Education Reform Now examined thirty-seven different variables across five realms:

1) Resources and Membership

2) Involvement in Politics

3) Scope of Bargaining

4) State Policies

5) Perceived Influence

The study analyzed factors ranging from union membership and revenue to state bargaining laws to campaign contributions, and included such measures such as the alignment between specific state policies and traditional union interests and a unique stakeholder survey. The report sorts the fifty-one jurisdictions into five tiers, ranking their teacher unions from strongest to weakest and providing in-depth profiles of each.

This timely study represents the most comprehensive analysis of American teacher unions' strength ever conducted, ranking all fifty states and the District of Columbia according to the power and influence of their state-level unions. To assess union strength, the Fordham Institute and Education Reform Now examined thirty-seven different variables across five realms:

1) Resources and Membership

2) Involvement in Politics

3) Scope of Bargaining

4) State Policies

5) Perceived Influence

The study analyzed factors ranging from union membership and revenue to state bargaining laws to campaign contributions, and included such measures such as the alignment between specific state policies and traditional union interests and a unique stakeholder survey. The report sorts the fifty-one jurisdictions into five tiers, ranking their teacher unions from strongest to weakest and providing in-depth profiles of each.

The late AFT president Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the NBPT. Photo from the Library of Congress.. |

As President of the AFT, the late Albert Shanker was instrumental in creating the National Board for Professional Teaching Standards (NBPTS) and much else in the education-reform world. Now Randi Weingarten is trying—earnestly and imaginatively—to return the organization and its (present) leader to the pantheon of real reformers.

Their new and much-ballyhooed proposal, contained in a report titled Raising the Bar, revives the Shanker-era idea of a “bar exam” for entering teachers—and charges the NBPTS with putting it into practice.

Andy Rotherham came out within hours with multiple doubts, some of which worry me, too. But let’s start by crediting Ms. Weingarten and her organization with a serious proposal to raise standards for new teachers as part of a broader effort to strengthen the profession.

Their proposal has three pillars. The second—but most important so far as I’m concerned— is this:

Teaching, like other respected professions, must have a universal assessment process for entry that includes rigorous preparation centered on clinical practice as well as theory, an in-depth test of subject and pedagogical knowledge, and a comprehensive teacher performance assessment.

My eye went immediately to the phrase “in-depth test of subject…knowledge,” and I combed the rest of the document seeking more on that topic—only to be dismayed by how little is actually said on the matter, other than that the NBPTS is supposed to figure it out. There is no hint of what in-depth knowledge might mean for a U.S. history teacher versus a geometry teacher versus an art teacher, nor does it address what sort of testing arrangement might gauge whether an individual possesses enough of it. (We know that the current arrangement—with most states relying heavily on the “Praxis II” test—does not do this well. We also know that some states do not take this issue on at all.)

The other two pillars, I have to admit, gave me pause. The first says “all stakeholders must collaborate”—a recipe for stasis and mediocrity if I’ve ever seen one. And the third assigns “primary responsibility for setting and enforcing the standards of the profession” to “members of the profession—practicing professionals in K–12 and higher education.” In other words, elected officials, employers, taxpayers, and parents can jolly well butt out; the standards governing classroom entry are none of their business. (I guess that’s true for think-tankers, too.)

Back to the “universal assessment”: I can easily understand why the AFT is giving that assignment to the NBPTS, but I’m not sure that organization is up to it—particularly the “knowledge” part. They administer very elaborate and expensive appraisals of teaching practice to veteran classroom practitioners, but I’ve never seen the National Board show much interest in subject-matter knowledge. Pedagogy, yes. Even lesson-planning. But not the causes and consequences of the Civil War or the ways that atoms combine to form molecules. Indeed, I’ve seen scant evidence that the powers-that-be at NBPTS even care much about such mundane stuff as content knowledge. (This part of the job, at least for grades K–8, should have been assigned to the Core Knowledge Foundation).

All of which is to say, the devil lurks prominently in details that are yet to be developed, not in the impulse to raise entry standards for teachers. (Unsurprisingly, this union-developed proposal deals only with new teachers, not with whether veteran instructors need to meet any standards of any sort.)

The Rotherham critique includes four more notable points.

Some of these are unanswerable within the framework of the AFT proposal and the NBPTS, the more so once it rounds up “all stakeholders.” But let’s not doom this baby at birth. Let’s welcome its arrival, wish it good health, cross our fingers (maybe even help if asked), and stand by ’til it can walk by itself. Thanks, Randi, for a proposal that would make Al proud—and that could conceivably do American education some good. Or could just as easily create nothing except false hope and, possibly, some damage.

This new study by Brookings’s Matt Chingos makes its way through the labyrinth of state budgets for standardized assessments, and it is the first time we’ve ever seen anything coherent and reasonably comprehensive on this part of the K-12 spending universe. Chingos focuses on the costs of contracts between states and test-making vendors, which comprise about 85 percent of total assessment costs. Across the forty-five states for which data were available, $669 million was spent annually on standardized assessments for grades three through nine. That’s about $27 per pupil on average, but this figure varies widely: A child in D.C. costs $114 to assess; in New York, that same child would cost just $7. Some of the variance is due to state size. He estimates that states with about 100,000 students in grades three-nine (e.g., Maine or Hawaii) spend about $13 more per pupil on assessment than states in the million-pupil range, such as Illinois. From these data, Chingos concludes that all states would enjoy some savings by joining or creating assessment consortia—whether PARCC or SBAC for ELA and math or another smaller grouping for other subjects. Much speculation surrounds the in-development Common Core assessments; the new design is likely to cost more, though it’s difficult to estimate how much at present. (We’ve also weighed in on this topic.) Chingos shows that new (and hopefully better) assessments could be rolled out at about the same cost to states, provided they pool resources and eke out quantity gains.

SOURCE

Mathew M. Chingos, Strength in Numbers: State Spending on K-12 Assessment Systems(Washington, D.C.: Brown Center on Education Policy at Brookings, November 2012).

Three years ago, Stanford’s Center for Research in Education Outcomes (CREDO) up-ended the conversation on charter school effectiveness with its much-cited study of sixteen states’ charter schools. This new report extends that kind of analysis into the Garden State, where the authors find a bumper crop of quality charters, particularly in Newark. CREDO analysts matched over 10,000 charter students in grades three through eight with “twin” students in traditional public schools (rigorously controlling for a host of student characteristics), tracking them between 2006-07 and 2010-11. The report offers a host of interesting data and solid ammunition for charter proponents in New Jersey—though its findings also raise a few serious questions. First, the good news for charters: Sixty percent of New Jersey charters outpace district learning gains in reading and 70 percent do so in math. And only 11 percent and 13 percent perform significantly worse (for reading and math, respectively). Statewide, charters added about two more months of annual learning in each subject compared to traditional public schools. Newark charters boast an additional seven and nine months’ learning in reading and math over the course of a year, respectively. Large positive effects in math were found for poor students and English language learners in charters, as well as small positive effects for black and Hispanic youngsters. Still, the report reveals shortcomings of charters too (some which—without further explanation—seem incongruous with the findings reported above). Notably, charter students in Jersey’s other four major cities (Camden, Jersey City, Paterson, and Trenton---which, with Newark, comprise the lion’s share of Garden State charters) performed worse in reading than their district peers (and on par in math). The report offers one takeaway: Policies matter—and those in NJ (including strict entry requirements, diligent closings of low-performers, and scaling up quality charters) should be praised, studied, and replicated. Huzzah, New Jersey! And huzzah, Newark!

Three years ago, Stanford’s Center for Research in Education Outcomes (CREDO) up-ended the conversation on charter school effectiveness with its much-cited study of sixteen states’ charter schools. This new report extends that kind of analysis into the Garden State, where the authors find a bumper crop of quality charters, particularly in Newark. CREDO analysts matched over 10,000 charter students in grades three through eight with “twin” students in traditional public schools (rigorously controlling for a host of student characteristics), tracking them between 2006-07 and 2010-11. The report offers a host of interesting data and solid ammunition for charter proponents in New Jersey—though its findings also raise a few serious questions. First, the good news for charters: Sixty percent of New Jersey charters outpace district learning gains in reading and 70 percent do so in math. And only 11 percent and 13 percent perform significantly worse (for reading and math, respectively). Statewide, charters added about two more months of annual learning in each subject compared to traditional public schools. Newark charters boast an additional seven and nine months’ learning in reading and math over the course of a year, respectively. Large positive effects in math were found for poor students and English language learners in charters, as well as small positive effects for black and Hispanic youngsters. Still, the report reveals shortcomings of charters too (some which—without further explanation—seem incongruous with the findings reported above). Notably, charter students in Jersey’s other four major cities (Camden, Jersey City, Paterson, and Trenton---which, with Newark, comprise the lion’s share of Garden State charters) performed worse in reading than their district peers (and on par in math). The report offers one takeaway: Policies matter—and those in NJ (including strict entry requirements, diligent closings of low-performers, and scaling up quality charters) should be praised, studied, and replicated. Huzzah, New Jersey! And huzzah, Newark!

SOURCE

Center for Research in Education Outcomes, Charter School Performance in New Jersey (Stanford, CA: CREDO, November 1, 2012).

A widely-noted Government Accountability Office (GAO) report back in June found that charter schools serve a disproportionately low number of special-education students, feeding concerns that these schools discriminate again special-needs (and ELL) youngsters. This latest from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) adds much-needed nuance and should quell some of the concern. CRPE analysts examined 2011-12 special-education enrollments across 1,500 district and 170 charter schools in New York State, finding that aggregates in that state mask important differences across grade band, location, and authorizer. At the middle and high school levels, New York special-education enrollments are nearly identical in the district and charter sectors, with the only variance—albeit sizable—occurring at the elementary level. (The authors offer a few suggestions as to why, including that charter elementaries are less likely to label students special-needs as they have more effective behavior-management systems, smaller classes, or a general insistence on “individualized” education for every pupil.) From these findings, the researchers draw cautionary policy recommendations, urging against the adoption (or continuation) of blanket special-education-enrollment requirements. (New York has such a law; more on this on our Choice Words blog). Not a bad first step, considering that such requirements often lead to over-identification of students as disabled. But let’s also recall the larger question: Why should a single school—charter or otherwise—be expected to appropriately serve all students?

A widely-noted Government Accountability Office (GAO) report back in June found that charter schools serve a disproportionately low number of special-education students, feeding concerns that these schools discriminate again special-needs (and ELL) youngsters. This latest from the Center on Reinventing Public Education (CRPE) adds much-needed nuance and should quell some of the concern. CRPE analysts examined 2011-12 special-education enrollments across 1,500 district and 170 charter schools in New York State, finding that aggregates in that state mask important differences across grade band, location, and authorizer. At the middle and high school levels, New York special-education enrollments are nearly identical in the district and charter sectors, with the only variance—albeit sizable—occurring at the elementary level. (The authors offer a few suggestions as to why, including that charter elementaries are less likely to label students special-needs as they have more effective behavior-management systems, smaller classes, or a general insistence on “individualized” education for every pupil.) From these findings, the researchers draw cautionary policy recommendations, urging against the adoption (or continuation) of blanket special-education-enrollment requirements. (New York has such a law; more on this on our Choice Words blog). Not a bad first step, considering that such requirements often lead to over-identification of students as disabled. But let’s also recall the larger question: Why should a single school—charter or otherwise—be expected to appropriately serve all students?

SOURCE

Robin Lake, Betheny Gross, and Patrick Denice, New York State Special Education Enrollment Analysis (Seattle, WA: Center on Reinventing Public Education, November 2012).