Restructuring Resources for High-Performing Schools

With ever increasingly tight public school budgets, Education Resource Strategies (ERS) could not be timelier in the release of its policy brief related to how to maximize school spending.

With ever increasingly tight public school budgets, Education Resource Strategies (ERS) could not be timelier in the release of its policy brief related to how to maximize school spending.

With ever increasingly tight public school budgets, Education Resource Strategies (ERS) could not be timelier in the release of its policy brief related to how to maximize school spending.

In Restructuring Resources for High-performing Schools, Karen Hawley Miles, Karen Baroody, and Elliot Regenstein take a careful look at barriers that make it difficult for public schools to use resources effectively and efficiently. In particular, ERS argues that state policymakers must address four areas in order to ensure the maximum effectiveness of their spending:

How schools organize personnel and time

With class-size reduction linked positively to student performance only in early elementary grades, class size requirements and required staffing ratios should be eliminated. Similarly, flexibility in meeting student needs can be achieved by eliminating seat time requirements in non-core subjects.

When it comes to teachers, policymakers should boot

state-mandated pay incentives tied to longevity and additional education and

replace them with those awarded to effective, high-contributing teachers. A

fair and transparent process for removing low-performing teachers should also

be created.

How districts and schools spend special education dollars

A myriad of restrictions make it difficult for special education funds to be cut or reallocated, often at the expense of general education students. Public schools should establish and support early intervention programs to reduce the number of students placed in the special education system, do away with rigid staffing requirements that don’t take student progress into account and provide incentives for teachers to obtain certification in both special education and specific content areas.

How districts allocate resources to schools and students

To dodge roadblocks put in place by restrictive categorical

funding, these fragmented funding streams should be combined and their goals

reanalyzed. Additionally, states should shift funding rules away from things

like time requirements and class sizes, and toward creating accountability

around outcomes.

What information districts gather on resources and spending

With 48 percent of education funding coming from state coffers, districts can significantly influence student performance by harnessing this funding and using it wisely. Districts should be encouraged to seek more transparency in their district-level resource use and outcomes.

In short, the name of the game is flexibility. By eliminating restrictive mandates and requirements and allowing for flexibility in fund allocation, public school funds may be more effectively used to meet the needs of all students and encourage high-performing teachers.

Restructuring Resources for High-Performing

Schools: A Primer for State Policymakers

Karen Hawley Miles,

Karen Baroody, and Elliot Regenstein

Education Resource

Strategies

June 2011

The growth of high-performing charter schools and charter-management organizations (CMOs) is critical for such schools to become sound alternative for more needy kids. To expand, however, CMOs must overcome the challenge of finding superior teachers and school leaders. To see how this has been done and can be done, this Center for American Progress report profiles Green Dot, IDEA Public Schools, High Tech High, KIPP, Rocketship Education, and Yes Prep and explains how these models have dealt with organizational growth and their associated human-capital challenges. It seems that these successful CMOs have three things in common: They formalize recruitment, training, and support processes and infrastructure; they get the most mileage from available talent by narrowing and better-defining staff roles; and they import and induct management talent. Toward that end, many of these organizations have developed their own recruiting tools and candidate evaluations. Some offer extensive professional development aligned with their organizational culture. Most believe in cultivating in-house talent, often by identifying future school leaders during the teacher-hiring process. Others have created and implemented their own certification programs. Well worth your attention, whether or not you’re a CMO junkie.

Preparing for Growth: Human Capital

Innovations in Public Charter Schools

Center for American Progress

May 2011

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation stipulated that a Title I school is in need of improvement if it fails to meet AYP for two consecutive years, and that students attending those schools are eligible to transfer to another public school within the district. How many students are taking advantage of this provision though? A new report by The Century Foundation found that fewer than two percent of the students eligible to transfer to higher performing schools within their district did so between 2003 and 2005. Also alarming is that an extremely small number of poor and minority children took advantage of the choice option. In 2004-05, 11 percent of eligible white students took advantage of the NCLB option, compared to only 0.9 percent of African Americans and 0.4 percent of Hispanics.

Part of the problem is that there is a short supply of schools that are not in need of improvement and eligible to receive transfer students. This report examines whether expanding students’ access to higher performing schools across districts would be a feasible policy. To identify which schools were eligible to send or receive students under the NCLB choice policy, The Century Foundation looked at all schools nationwide, excluding D.C. and Hawaii as they each only have one school district, and magnet and alternative schools because they operate under different admission requirements. The remaining schools were then categorized by their AYP scores. Schools failing to meet AYP for two of the last three years were identified as eligible sending schools (9.9 percent) and the remaining schools were classified as eligible receiving schools (90.1 percent).

The report found that an interdistrict choice policy has the potential to expand access to higher performing schools for students nationwide. The analysis revealed that 94.5 percent of eligible sending schools have no access to higher-performing schools under the current intradistrict choice policy, and estimates that an interdistrict choice policy has the potential to expand access and increase participation by almost five times nationally, and by 14 times in Ohio. While interdistrict choice has the potential to allow a significant number of kids to participate the report also warns that if such a policy is not controlled and targeted to reach the kids most in need, it could further intensify existing racial and socioeconomic inequalities.

Can

NCLB Choice Work? Modeling the Effects of Interdistrict Choice on Student

Access to Higher-Performing Schools

A Century Foundation

Report

Meredith P. Richards,

Kori J. Stroub, and Jennifer Jellision Holme

Among the many differences the conference committee must resolve between the House and Senate versions of the state budget is a Senate provision that would reward exceptional charter schools with low-cost facilities. Specifically:

Gene Harris, superintendent of Columbus City Schools, Ohio’s largest district and one with a history of blocking charter schools from its unused facilities, is opposed to the change. Her reasons include that charters might not have sufficient funds to maintain a facility and that it prevents the district from leasing to other “important” organizations. These are valid concerns, and the conference committee could amend the provision to address them. But this seems like yet another instance where anti-charter sentiment among the education establishment is so ingrained that districts struggle to recognize those pro-charter policies that can actually benefit them.

For starters, this provision is fiscally smart for districts. If a district must maintain unused facilities regardless, why not lease to a charter school that will pick up those costs? Further, this provision requires districts to lease, not sell, the space (as current law requires), so if a district’s enrollment rebounds or it otherwise needs to use the space in question, it can certainly reassume occupation and care of the facility down the road. And let’s not forget that the buildings charter schools are after are older ones that, for the most part, are emptying out because the state is pouring billions into building fancy new schools for districts.

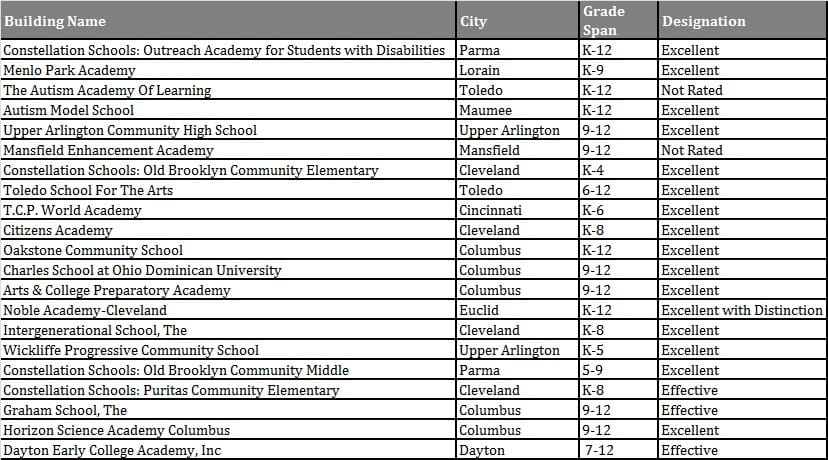

Second, this provision is good for students. It encourages the growth of high-performing schools, not the unchecked flourishing of lousy ones. Consider the $1-annual-lease clause. Last school year, 3,503 Ohio school buildings had a Performance Index score (another 172, for various reasons, did not). Because of the overall mediocre performance of the state’s charter schools (and this budget bill separately tackles the issue of charter quality), just 21 charter schools statewide would meet the bar for the $1 annual lease (see Chart 1 for the list of qualifying schools).

These are schools that any urban superintendent should be comfortable “losing” students to – schools like Citizens Academy and the Intergenerational School, both in Cleveland and members of the Breakthrough Schools network of high-flying charter schools; Dayton Early College Academy in Fordham’s hometown; the Charles and Graham Schools at Ohio Dominican University; and Arts & College Preparatory Academy in Columbus. All of the schools that make the cut are out-performing their home school districts and many are doing it whilst serving the neediest and most challenging students in their communities.

Chart 1. Charter schools in the top 50 percent of all Ohio public schools by Performance Index score, 2009-10

Unlike the notoriously bad charter provisions inserted in the budget bill by the Ohio House (and rightly and swiftly removed by the Senate), this charter policy change is one that districts should embrace. They should let go of their instinctive, immediate opposition to anything that could “help” the competition and instead be supportive of those policies that can be mutually beneficial and, most importantly, improve education options for students.

Earlier this month Fordham released an analysis in the national Education Gadfly showing that when it comes to serving kids in the neediest communities, charter school start-ups have a far greater chance (nearly quadruple) of success than a district turnaround. David Stuit - who also authored Fordham’s recent study on the dearth of successful school turnarounds: Are Bad Schools Immortal? – examined select charter start-ups and district turnarounds in Ohio along with nine other states to determine their chance of success (scoring above the state average). He finds:

In most of the showdowns, the charter start-ups emerged victorious. Of the eighty-one head-to-head matchups I identified, 19 percent of the charter schools (i.e. fifteen schools) tested above the state average in 2008-09, compared with 5 percent of district schools (i.e. four schools).*

To be clear, Stuit’s definition of a “turnaround” is narrow – “a school must have moved the needle on student achievement in both reading and math from its state’s bottom decile to above the state average (from 2003-04 to 2008-09).” And he admits that “caveats abound”: the sample size in this analysis was small; charter schools’ success rates may be overestimated through selection bias; and there were loads of unsuccessful start-up charters in his study that merit a whole separate policy conversation. (Read more about the methodology and the limits of the study here and here.) Stuit concludes:

When contemplating whether to put

one’s energy and resources into turning around failing schools or closing them

and replacing them with charter start-ups, the answer for most cities will

probably be “both, and” rather than “either, or.” … Reformers will need to get

a whole lot better at implementing both strategies

successfully lest all of this add up to “nothing much.”

School turnaround landscape in Ohio

To be sure, the Buckeye State should be fostering room for school turnarounds regardless of whether traditional school districts or CMOs or one-off charter schools (or some yet-to-be created entities) are at the helm. But, as Ohio moves forward in overhauling chronically failing schools – precipitated not only by federal money (Race to the Top and School Improvement Grants) but also by policies (such as those proposed by Gov. Kasich) – there are at least three important facts to keep in mind that add nuance to the school turnaround conversation.

School turnaround

work is extraordinarily difficult. Fordham has witnessed firsthand

how even charter turnarounds – less hampered by external restraints on

innovation – can crash and burn. About one percent of schools Stuit studied

successfully turned themselves around. Despite the recent push for turnarounds,

the concept of school reconstitution dates back to the No Child Left Behind

Act, under which schools that persistently failed to make AYP were supposed to

undergo restructuring. Considering that nearly all such schools in Ohio

continue to languish a decade later – like Champion Middle School in Columbus,

which we’ve

chronicled before – it doesn’t exactly inspire hope for the next go around.

Still, despite this poor track record, under the governor’s

budget 93 schools (those ranked in the bottom five percent for three years)

would face reconstitution, about the same

number that failed to make AYP and theoretically should have been

restructured successfully a few years ago. This isn’t to say that Ohio should

sit by idly and ignore its lowest performing schools – just a reminder that,

thus far at least, we don’t really know how to repair them.

Ohio’s turnaround plan includes some inconsistencies. The state’s biennial budget bill stipulates that schools ranked in the lowest five percent of schools (according to Performance Index score) for three years must face turnaround. Options include closing the school and reassigning students; contracting with another entity (district, non- or for-profit, etc.) to operate the school; replacing the principal and all teaching staff; or re-opening the school as a conversion charter. However, among the schools on the turnaround list – as identified by the budget criteria – are 13 schools that received SIG grants totaling $37,546,632. SIG turnaround options are far looser, and include options to keep staff in place, or use professional development as the primary vehicle of transformation. Would these 13 schools get to stick with their original SIG turnaround plans or would their overhaul plans need to match those of the other sanctioned schools across Ohio? Further, Ohio received a total of $132 million in SIG money to implement turnarounds, but Ohio’s turnaround plan does not provide funding for it. This isn’t to say that dumping millions of dollars into failing schools will fix the problem (history tells us it likely won’t), but the messaging on turnarounds coming from the federal and state levels is inconsistent.

The human capital challenge must be addressed for any hope of turnaround success. School turnaround success hinges on teacher and principal leadership. In our previous analysis of Ohio’s turnaround plan, we asked:

Does Ohio have enough teaching and leadership talent willing to take over 93 schools, or charter management groups capable of taking some of them on?

Terry Ryan highlighted this fact in his chapter for the Center on Reinventing Public Education’s “Hopes, Fears, and Reality” back in early 2010:

Having a plan for reform is important, but equally or more important is having a team in place that can implement the plan and see it through to its conclusion. As straightforward… as this conclusion may be in theory, in practice it is hard for many mid-size cities to act on it. There are simply not enough gifted school leaders and teachers ready and willing to jump into the fray.

Some nationally renowned turnaround programs – like the turnaround specialist training program at the University of Virginia – are at work in Ohio schools; some Cincinnati schools have already seen improvements with the help of this model, and several Akron schools will be helped by the program this year. But in recruiting talent more broadly – charter management organizations capable of scaling up, teachers to keep the pipeline full, and leaders to transform nearly 100 schools – Ohio needs a serious plan.

Perhaps the most feasible strategy is to push hard for a significant number of these schools to close. Closure is one of several options allowed under Kasich’s budget and SIGs, and Stuit found in his original analysis that Ohio did a decent job (more so than other states) of closing poor performers rather than turning them around. Or – taking a cue from Louisiana, Tennessee, and now possibly our neighbor to the northwest – might the Buckeye State be better off with a coherent turnaround plan driven by a single statewide school district overseeing the bottom tier of schools (akin to New Orleans’ “Recovery School District”)? Such innovative school governance options are untested in Ohio, but are they any riskier than traveling down the same turnaround road, which – for the vast majority of youngsters trapped in failure – has led to continued failure?

Nikki Baszynski reflects on the eighth-grade graduation ceremony at Columbus Collegiate Academy (CCA), a Fordham-authorized middle school serving students in grades six through eight (the vast majority of whom are economically disadvantaged). CCA recently won the Gold Star EPIC award from New Leaders for New Schools for its extraordinary student achievement gains, placing it among only four schools nationally to win the honor. In short, its eighth-grade graduates are among the best prepared incoming high schoolers in the city of Columbus, if not the whole state. Nikki was a founding teacher at the school, is a Teach For America alumna, and is now pursuing her juris doctorate at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law.

As we waited for the elevator, I looked to my left and saw a sign above the drinking fountain declaring, “Whites Only.” Two Columbus Collegiate Academy graduates – one black, one Hispanic – noted the sign, too, and continued to read the commentary below it. The remaining portion of the sign explained the historic division of the races, recognized the efforts made to close that gap, and then ultimately welcomed all who read the sign to drink freely from the water fountain. As we finished reading, the elevator doors opened and we rode to the third floor of the King Arts Complex.

The King Arts Complex of Columbus, Ohio, is devoted to increasing awareness of the “vast and significant contributions of African Americans” to our country and the world. It was a fitting location for the first Columbus Collegiate Academy eighth-grade graduation, an event three years in the making and one of the many efforts across this nation to close the achievement gap. There’s no question that graduates from Columbus Collegiate Academy, where 81 percent of the students are African American and 94 are economically disadvantaged – but achieve scores that place them among the nation’s best, will be among those making vast contributions to our community.

Founder and Executive Director Andrew Boy began the program by thanking everyone who made CCA’s success possible and introducing guest speaker Ray Miller, a former member of the Ohio General Assembly. Miller offered words of encouragement and advice to the graduates, ending with Marianne Williamson’s quote, “As we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same.” Certainly, CCA’s students and their success have lit the path for fellow schools to aspire to the same high expectations and believe that those expectations can be met with a rigorous curriculum, a dedicated staff, and a culture of excellence.

The graduation ceremony also featured four student speakers: the class poet, co-valedictorians, and salutatorian. Each student’s speech conveyed a similar message about the CCA experience: the path was hard, the teamwork necessary, and the results great. They recalled the nervousness with which they began, the excitement with which they are leaving, and the gratitude they have for all those who helped them along the way. One of CCA’s valedictorians recognized the historic nature of the moment and its binding power on all the graduates: “We’re not just classmates or associates, we are a family…and we will always be the founding class of Columbus Collegiate Academy.”

Ms. Kathryn Anstaett, CCA’s social studies teacher, captured the widespread feelings of possibility and enthusiasm, and exemplified the school’s culture of high expectations and dedication, when she said, “I’m so happy and excited that people like you are going to be leaders of the future because you have passion, compassion, empathy, tolerance, and problem-solving skills that I know are going to make our world, our country, greater in the future than it is today.”

The program ended with advice and kind words from Minister Rhesa Green and each student walking to the front of the room to receive a diploma. The audience clapped, cheered, and celebrated the end of the students’ three-year journey at CCA. But, the “Class of 2019” banner that hung above the students ensured no one forgot that the end of their time at CCA was really just one more step toward their ultimate goal – college graduation. And thanks to CCA, each of them has the skills, knowledge, and passion to achieve that goal.

Though the era of “Whites Only” signs has passed, racial segregation and its impacts on student achievement– especially in our schools – have not. I am sure CCA’s graduates will continue to encounter systemic roadblocks throughout their lives, but, I am also certain that when faced with a roadblock, they will do what they’ve been trained to do at CCA through the culture of high expectations and an unrelenting pursuit of success: acknowledge its existence and then proudly rise above it.

With ever increasingly tight public school budgets, Education Resource Strategies (ERS) could not be timelier in the release of its policy brief related to how to maximize school spending.

In Restructuring Resources for High-performing Schools, Karen Hawley Miles, Karen Baroody, and Elliot Regenstein take a careful look at barriers that make it difficult for public schools to use resources effectively and efficiently. In particular, ERS argues that state policymakers must address four areas in order to ensure the maximum effectiveness of their spending:

How schools organize personnel and time

With class-size reduction linked positively to student performance only in early elementary grades, class size requirements and required staffing ratios should be eliminated. Similarly, flexibility in meeting student needs can be achieved by eliminating seat time requirements in non-core subjects.

When it comes to teachers, policymakers should boot

state-mandated pay incentives tied to longevity and additional education and

replace them with those awarded to effective, high-contributing teachers. A

fair and transparent process for removing low-performing teachers should also

be created.

How districts and schools spend special education dollars

A myriad of restrictions make it difficult for special education funds to be cut or reallocated, often at the expense of general education students. Public schools should establish and support early intervention programs to reduce the number of students placed in the special education system, do away with rigid staffing requirements that don’t take student progress into account and provide incentives for teachers to obtain certification in both special education and specific content areas.

How districts allocate resources to schools and students

To dodge roadblocks put in place by restrictive categorical

funding, these fragmented funding streams should be combined and their goals

reanalyzed. Additionally, states should shift funding rules away from things

like time requirements and class sizes, and toward creating accountability

around outcomes.

What information districts gather on resources and spending

With 48 percent of education funding coming from state coffers, districts can significantly influence student performance by harnessing this funding and using it wisely. Districts should be encouraged to seek more transparency in their district-level resource use and outcomes.

In short, the name of the game is flexibility. By eliminating restrictive mandates and requirements and allowing for flexibility in fund allocation, public school funds may be more effectively used to meet the needs of all students and encourage high-performing teachers.

Restructuring Resources for High-Performing

Schools: A Primer for State Policymakers

Karen Hawley Miles,

Karen Baroody, and Elliot Regenstein

Education Resource

Strategies

June 2011

The growth of high-performing charter schools and charter-management organizations (CMOs) is critical for such schools to become sound alternative for more needy kids. To expand, however, CMOs must overcome the challenge of finding superior teachers and school leaders. To see how this has been done and can be done, this Center for American Progress report profiles Green Dot, IDEA Public Schools, High Tech High, KIPP, Rocketship Education, and Yes Prep and explains how these models have dealt with organizational growth and their associated human-capital challenges. It seems that these successful CMOs have three things in common: They formalize recruitment, training, and support processes and infrastructure; they get the most mileage from available talent by narrowing and better-defining staff roles; and they import and induct management talent. Toward that end, many of these organizations have developed their own recruiting tools and candidate evaluations. Some offer extensive professional development aligned with their organizational culture. Most believe in cultivating in-house talent, often by identifying future school leaders during the teacher-hiring process. Others have created and implemented their own certification programs. Well worth your attention, whether or not you’re a CMO junkie.

Preparing for Growth: Human Capital

Innovations in Public Charter Schools

Center for American Progress

May 2011

No Child Left Behind (NCLB) legislation stipulated that a Title I school is in need of improvement if it fails to meet AYP for two consecutive years, and that students attending those schools are eligible to transfer to another public school within the district. How many students are taking advantage of this provision though? A new report by The Century Foundation found that fewer than two percent of the students eligible to transfer to higher performing schools within their district did so between 2003 and 2005. Also alarming is that an extremely small number of poor and minority children took advantage of the choice option. In 2004-05, 11 percent of eligible white students took advantage of the NCLB option, compared to only 0.9 percent of African Americans and 0.4 percent of Hispanics.

Part of the problem is that there is a short supply of schools that are not in need of improvement and eligible to receive transfer students. This report examines whether expanding students’ access to higher performing schools across districts would be a feasible policy. To identify which schools were eligible to send or receive students under the NCLB choice policy, The Century Foundation looked at all schools nationwide, excluding D.C. and Hawaii as they each only have one school district, and magnet and alternative schools because they operate under different admission requirements. The remaining schools were then categorized by their AYP scores. Schools failing to meet AYP for two of the last three years were identified as eligible sending schools (9.9 percent) and the remaining schools were classified as eligible receiving schools (90.1 percent).

The report found that an interdistrict choice policy has the potential to expand access to higher performing schools for students nationwide. The analysis revealed that 94.5 percent of eligible sending schools have no access to higher-performing schools under the current intradistrict choice policy, and estimates that an interdistrict choice policy has the potential to expand access and increase participation by almost five times nationally, and by 14 times in Ohio. While interdistrict choice has the potential to allow a significant number of kids to participate the report also warns that if such a policy is not controlled and targeted to reach the kids most in need, it could further intensify existing racial and socioeconomic inequalities.

Can

NCLB Choice Work? Modeling the Effects of Interdistrict Choice on Student

Access to Higher-Performing Schools

A Century Foundation

Report

Meredith P. Richards,

Kori J. Stroub, and Jennifer Jellision Holme