Exposing traditional school districts to greater competition is a central goal of education reform in the United States. Yet because of the complexity of reform efforts, quantifying "competition" is challenging.

In this report, Fordham analysts David Griffith and Jeanette Luna use data from multiple sources to estimate how much competition the 125 largest school districts in the United States face for students, how the answer to that question differs by student group, and how the competition facing each district has increased or decreased in the past decade.

Interactive figures embedded in the report allow readers to see how specific forms of competition have evolved in particular communities.

Foreword

By Amber M. Northern and Michael J. Petrilli

In many communities, public school systems compete with an increasingly complex and frequently overlapping set of alternatives for students and families, including charter schools, public schools in other districts, voucher programs, tax-credit scholarships, and education savings accounts, as well as traditional private schools, microschools, and homeschooling.

We at Fordham view this as a healthy development, both because we believe in the fundamental right of parents to choose schools that work best for their children, and because of the large and ever-growing research literature demonstrating that competition improves achievement in traditional public schools. That “competitive effects” are largely positive should be seen as good news for everyone, as all of us should root for every sector of American education to improve. And it means that the whole “school choice versus improving traditional public schools” debate presents a false dichotomy; we can do both at the same time. Indeed, embracing school choice is a valuable strategy for improving traditional public schools.

Yet, despite the amount of attention that school choice receives in the media and among policy wonks, politicians, and adult interest groups, the extent of actual competition in major school districts is not well understood. We were curious: Which education markets in America are the most competitive? And which markets have education reformers and choice-encouragers neglected or failed to penetrate?

Those questions prompted this analysis, conducted by David Griffith and Jeanette Luna, Fordham’s associate director of research and research associate, respectively. The study seeks to quantify the extent to which competition is occurring by estimating the number of students enrolled in charter, private, and homeschools in each of the nation’s 125 largest school districts in spring 2020 and then dividing that sum by an estimate of a given district’s total student population (which includes students in traditional public schools). The resulting quotient—the report’s measure of the competition facing a district—is the combined market share of all non-district alternatives. While this is not a perfect measure (we can’t account for inter-district open enrollment, for instance), it is as good an estimate as current data allow.

In addition to calculating the competition districts face for all students, David and Jeanette also crunch the numbers for individual subgroups, including Black, White, Hispanic, and Asian students, to determine the percentages of school-age children in those subgroups who are attending non-district alternatives.

As the report explains, even calculating these seemingly simple figures required a bewildering number of decisions. For example, because of the variation in state and local kindergarten policies and the data conundrum relative to high school dropouts, the report relies on enrollment in grades 1–8.

In the end, the study’s findings reveal several interesting patterns. First, most of America’s largest districts face only modest competition for students (though there is considerable variation). In the median district, approximately 80 percent of students enroll in a district-run school, and approximately 95 percent of students do so in the country’s “Least Competitive Large District,” Clayton County, Georgia. Meanwhile, the country’s “Most Competitive Large District”—Orleans Parish, Louisiana, where there are no district-run schools due to reforms implemented in the wake of Hurricane Katrina[FW1]—is a clear outlier. In the country’s second and third most competitive districts, the San Antonio Independent School District (TX) and the District of Columbia Public Schools (DC), only half of students enroll in non-district schools.

In addition to facing low levels of competition in general, most large districts face more competition to educate White students than they do to educate their non-white peers. After all, White students are much more likely to attend private schools. Yet between 2010 and 2020, the ground shifted: More districts are now competing to educate non-white students, thanks largely to the growth of charter schools. Specifically, 116 of 125 large districts saw an increase in non-white students’ access to non-district alternatives in the last decade (with the median large district seeing a 7 percentage point increase). The co-authors commend this trend even as they conclude that we need more, as well as more affordable, non-district alternatives, especially for traditionally disadvantaged groups.

The full report includes several interactive figures that allow readers to see how specific forms of competition have evolved in specific districts and racial subgroups. So, by all means, jump in and click around to your heart’s content.

But before you do—especially if you’re an education reformer keen to expand school choice for kids who need it—take a look at the following table, which shows major urban districts where relatively few students of color attended non-district alternatives as of 2020 (ranked one through seventy). In our view, the districts that appear towards the top of this list are ideal targets for charter school expansion.

Table FW-1: Major urban districts that face the least competition to educate non-white students

Notes: Urban districts are those where private, charter, and traditional public schools with urban locale codes account for more than half of total public and private enrollment.

Let's focus on the twenty major urban districts with the least competition. Table FW-1 shows that two of these districts (Cherry Creek School District 5 and Mobile County) are located in Colorado and Alabama, which have the second and third best “state public charter school laws” (respectively) in the nation, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. Fayette and Jefferson County school districts in Kentucky and several urban districts in Texas—including in Plano, El Paso and Round Rock—are also in dire need of more options for students of color. The same can be said for Black and Brown kids in multiple urban districts in charter-friendly North Carolina, including in the counties of Forsyth, Cumberland, Wake, Guilford, and Mecklenburg. Making more progress in Nevada could also have a big payoff, given the underperformance of Washoe County (i.e., Reno), where just 12 percent of students of color attend an option other than their district-run school.

So, a big heads-up to school choice advocates in search of fertile terrain. Take a good look at these districts because they need you. They need your energy, your resources, and your commitment to expand charter schools and other options.

Because, at the end of the day, just 7 percent of all public school students attend a public charter school. It’s a proverbial yet precious drop in the bucket. Look, we already know that the growth of high-quality charter schools benefits low-income, Black, and Hispanic students academically. So, it follows that we need more of them.

Who’s listening?

Introduction

Exposing traditional school districts to greater competition is a central but typically unstated goal of education reform in the United States. The case for greater competition rests on two pillars: First, basic economic theory suggests that competitive markets are more efficient than monopolies, at least when appropriately regulated. Second, a growing empirical literature suggests that, despite the inevitable market failures, competition really does work in K–12 education, as it does in most other fields. Monopolies, in the view of many informed observers, are by their nature indifferent to the needs of those they are meant to serve, even when they reflect the will of a fractious majority and especially when they are in thrall to one or more interest groups (as is too often the case).

Yet, despite widespread agreement that competition is desirable, quantifying it is difficult. Outside of track meets and soccer games, we seldom observe competition between schools and districts. Rather, we infer its presence or absence from the movement of students and the presence or absence of enabling conditions. For example, when two charter schools with similar grade spans, missions, and pedagogies locate on the same New York City block, it seems reasonable to assume that they are in competition with one another (after all, families who live within striking range are free to enroll their children in either school, space permitted). In contrast, when there are no charter or private schools within driving distance of a traditional public school, it seems reasonable to assume that competition for the students who live in that school’s attendance zone is minimal (though because Americans have the right to homeschool their children, no school district in the United States is a pure monopoly).

Of course, traditional school districts can also compete, both with one another and with the various alternatives. And in rare cases, enterprising jurisdictions have created programs that have succeeded in fostering internal competition (that is, between district-run schools or programs). Yet, while there is evidence that it has fostered healthy competition in some places, in practice interdistrict open enrollment rarely benefits traditionally disadvantaged students.[1] And even in the growing number of systems with some variant of intradistrict school choice, the incentive to improve is often blunted by the dearth of meaningful consequences for adults when low performance persists.

In short, districts that don’t have to compete for traditionally disadvantaged students can afford to take them for granted, which increases the odds that they will be poorly served. Hence the decades-long quest to create truly independent alternatives to America’s largest school districts—to encourage them to improve and to provide students with viable alternatives should they fail to do so—and the need to periodically assess that endeavor’s success.

Introducing The Education Competition Index: a comparable measure of the “competition” facing the 125 largest school districts in the United States.

WHAT DO WE KNOW ABOUT THE EFFECTS OF COMPETITION?

Research suggests that schools perform better when students aren’t obliged to enroll in them.[2] For example, at least twelve studies that rely on student-level data have found that competition from charter schools has positive or neutral-to-positive effects on traditional public school achievement,[3] while just three studies[4] have found negative effects.[5] Moreover, research also suggests that charters (which nearly always are obliged to compete for students) tend to boost the achievement of students who enroll in them, at least in urban areas.[6] For example, the most recent national analysis by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes (CREDO) finds that students in charters gain the equivalent of sixteen days of learning in reading and six days of learning in math per year.[7] And the literature on charters’ systemic effects—that is, their effects on the average achievement of all publicly enrolled students including those in traditional public schools—is similarly positive.[8]

If anything, the research on competition from private schools is more positive.[9] For example, at least nineteen studies of publicly funded private school choice programs have found positive or neutral-to-positive effects on the academic progress of students who remain in traditional public schools (though in many cases, these effects were small).[10] Yet, to our knowledge, no study has found negative effects. Although some studies overlap geographically, positive competitive effects from public and/or private school choice have now been detected in Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Milwaukee, New York City, North Carolina, and Texas, as well as several national analyses.

Admittedly, the research on the effects of participating in private school choice programs is more complex, with studies of urban programs finding more positive effects and those of statewide programs finding more negative effects, at least in the United States.[11] Access to private school choice, of course, is not confined to voucher programs. But assessing the overall performance of private schools is a fraught endeavor, absent a natural experiment and common assessments (from which private schools are typically exempt). And for similar reasons, we know almost nothing about the effects of homeschooling. Finally, we know less than we would like about how competition of any sort affects outcomes other than academic achievement, though the limited evidence that does exist on such outcomes is also positive.[12]

Data and Methods

To generate a comparable measure of the “competition” facing school districts, we first estimate the number of students enrolled in charter, private, and homeschools in a given geographic school district in the 2019-2020 schoolyear (i.e., the most recent year for which data on all three alternatives are available) and then divide the resulting sums by our estimates of the total student population (which include students in traditional public schools). In other words, our chosen measure of competition (which is reminiscent of market concentration measures) is the combined market share of all non-district alternatives.

Although this measure could theoretically be supplemented with other commonly used proxies for competition, such as measures of entry rates and/or barriers to entry, in practice these alternatives are challenging to operationalize (for example, one of the principal barriers to charter school entry is a hostile political environment, which is difficult to quantify). So, for simplicity’s sake, the report focuses on the most indisputable evidence of competition (i.e., non-district enrollment).

Similarly, although competition and school choice are closely related concepts, our estimates do not include those forms of school choice, such as magnets schools and other intradistrict choice programs, that do not generate competition from the district’s perspective. Nor do we include interdistrict open enrollment, although we do include district-authorized charter schools on the grounds that they typically lack attendance zones (or any sort of neighborhood preference) and thus compete with traditional public schools for students.

Because a nontrivial percentage of students drop out at some point in high school, we also exclude grades 9–12 from our analysis. And because some states/districts don’t require or fund Kindergarten, we also exclude this year (in addition to preschool). In other words, the report’s focus is the competition districts face for students in grades 1–8.

Because education markets are often segmented in practice, in addition to overall rankings, we also estimate competition within the four biggest racial subgroups: White, Hispanic, Black, and Asian. Furthermore, although the first half of the report is based exclusively on data from 2020, the latter half also includes estimates of total and subgroup competition for the preceding decade (i.e., from 2010–20).

To generate those estimates, we first assigned traditional public, charter, and private schools to geographic school districts based on their longitude and latitude and then aggregated their enrollment data for grades 1–8 at the district level (as discussed below, the process for homeschooling is different).

Data on charter and traditional public school location and enrollment come from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Common Core of Data and are essentially comprehensive for the years and districts in question; however, because many virtual schools’ catchment areas extend far beyond the borders of their districts, we excluded these schools when estimating charter and traditional public school enrollment in individual districts.[13]

Data on private schools come from the biannual Private School Universe Survey (PSUS), which is also conducted by NCES. To estimate private school enrollment in the years when the survey wasn’t administered, we first aggregated the data at the geographic school district level and then interpolated (i.e., took a simple average of the values from the two adjacent years). To adjust for nonresponse, we used the school-by-year weights provided by NCES[14] and took a simple moving average of up to five years of data.[15] Because the PSUS doesn’t include school-by-grade level data on race, we estimated White, Hispanic, Black, and Asian enrollment in grades 1–8 by multiplying total enrollment in these grades by the relevant school-by-year-level percentages and then following the other steps outlined above.

Finally, data on homeschooling enrollment come in two forms: First, after conducting a search of state department of education websites and contemporaneous news articles, we were able to locate at least one year of official, pre-pandemic, district-level data on total K–12 homeschooling enrollment for twelve of the thirty-four states with one or more “large” school districts, of which ten had counts that we deemed reliable enough to utilize.[16] Second, to estimate homeschooling rates for districts in the other twenty-six states, we relied on the Parent and Family Involvement in Education Survey of the National Household Education Surveys Program, which was administered in 2012, 2016, and 2019. Of the various data sources, the survey is the least informative if generating district-level estimates is the goal. So, to generate district-specific estimates of homeschool enrollment in the relevant states, we took three steps: First, we took a weighted average of the national estimates for the relevant grade levels for each wave of data. Second, we averaged the resulting estimates, on the grounds that whatever trends they exhibited were as likely to be driven by sampling error as by actual changes.[17] Finally, we adjusted the resulting national averages based on the percentages of students in a district’s traditional public, charter, and private schools who were White, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and “other,” as well as the percentages of all students in those institutions whose schools were classified as urban, suburban, town, and rural.[18] In practice, taking this approach means our estimates for homeschooling in these states vary considerably between districts but relatively little within them.

Although these methods preclude the generation of precise confidence intervals, the limitations of the data mean there is some uncertainty associated with our estimates. Accordingly, we have rounded the resulting estimates to the nearest percentage point for the purposes of the report’s narrative as well as the tables.

In general, our sense is that these estimates are relatively insensitive to the specific choices we have made with regard to the data (see Technical Appendix). However, it is important to recognize that they are all “pre-Covid” and likely understate the current level of competition in some locales, given the documented increases in charter[19] and private school enrollment, as well as homeschooling, in the last few years.[20]

The National Context

Nationally, the proportion of students in grades 1–8 who were not enrolled in a district-run school increased by about three percentage points between 2010 and 2020, from roughly 15 percent to approximately 18 percent. Per Figure 1, this increase was driven by the growth of charter schools, which more than doubled their market share from 3 percent to 6.5 percent; however, of the students in grades 1–8 who didn’t attend a district school in spring 2020, nearly half still attended a private school and perhaps one in five were homeschooled.

Importantly, these national averages mask considerable differences between the major racial/ethnic subgroups. For example, of the White students in grades 1–8 who didn’t enroll in a district-run school in 2020, nearly three-fifths attended a private school, while just one-fifth were enrolled in a charter school, and roughly the same percentage were homeschooled. In contrast, more than half of non-White students in grades 1–8 who weren’t enrolled in a district-run school in 2020 attended a charter school, about one-third attended a private school, and approximately one in seven were homeschooled.

Figure 1: Nationally, non-district enrollment in grades 1-8 increased slightly between 2010 and 2020 thanks to the growth of charter schools.

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of U.S. students in grades 1–8 who enrolled in a charter, private, or home school between 2010 and 2020. Data on charter, private, and homeschool enrollment come from the Common Core of Data, the Private School Universe Survey, and the Family Involvement in Education Survey, respectively.

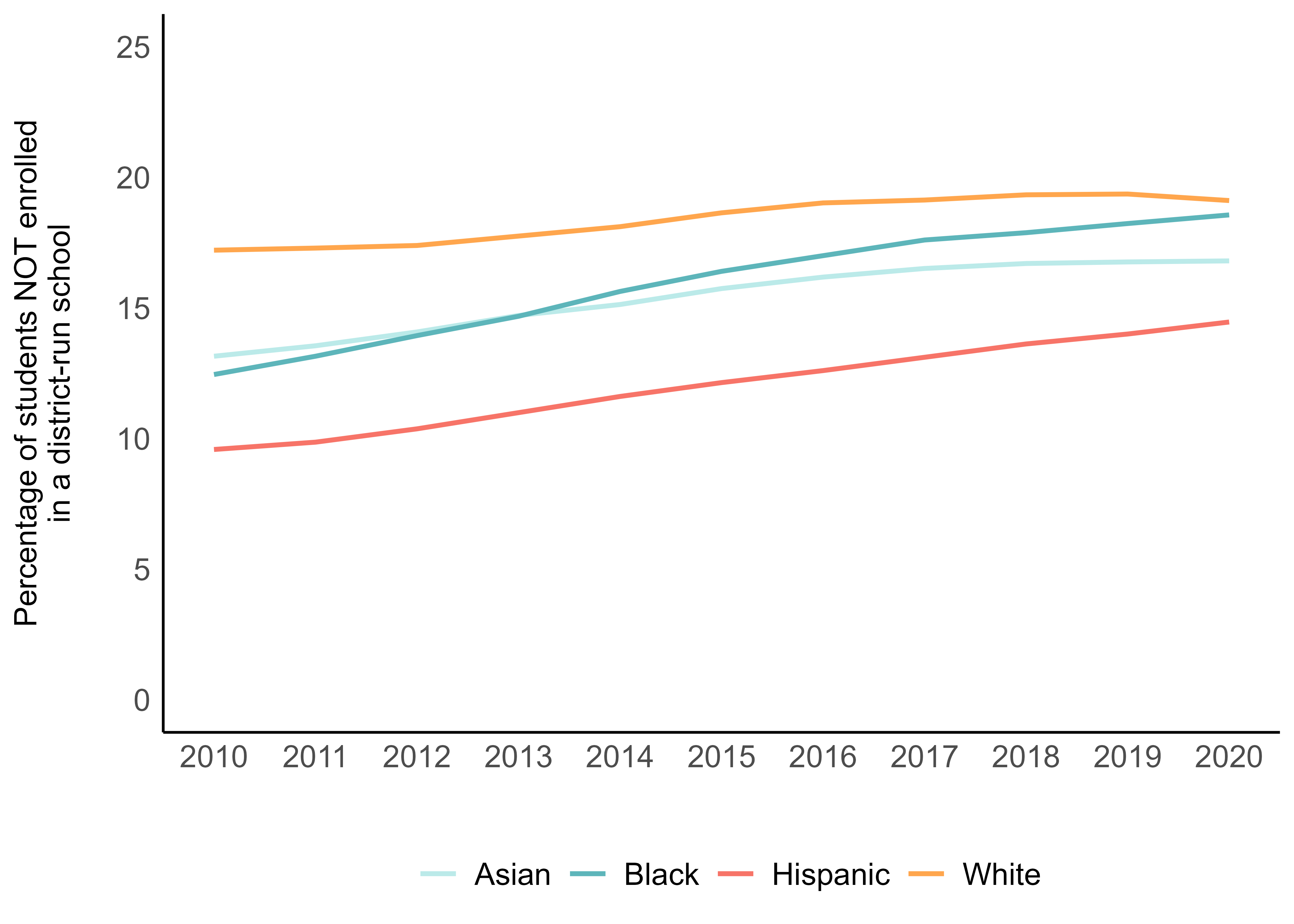

Overall, about 19 percent of White students, more than 18 percent of Black students, roughly 17 percent of Asian students, and approximately 14 percent of Hispanic students in grades 1–8 were enrolled in non-district schools heading into the pandemic (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The national increase in non-district enrollment in grades 1–8 was concentrated among Black and Hispanic students.

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of U.S. students in grades 1–8 in each of the four biggest racial subgroups who did not enroll in a district-run school between 2010 and 2020.

Per the figure, the share of White students not enrolled in a district-run school increased by about two percentage points between 2010 and 2020 (or about 10 percent). The share of Asian students in non-district schools increased by about three and a half percentage points (or about 25 percent). And the equivalent shares of Hispanic and Black students increased by five and six percentage points respectively (or approximately 50 percent).

Below, we present results for America’s largest school districts.

FINDING 1: MOST OF AMERICA’S LARGEST SCHOOL DISTRICTS FACE ONLY MODEST COMPETITION FOR STUDENTS

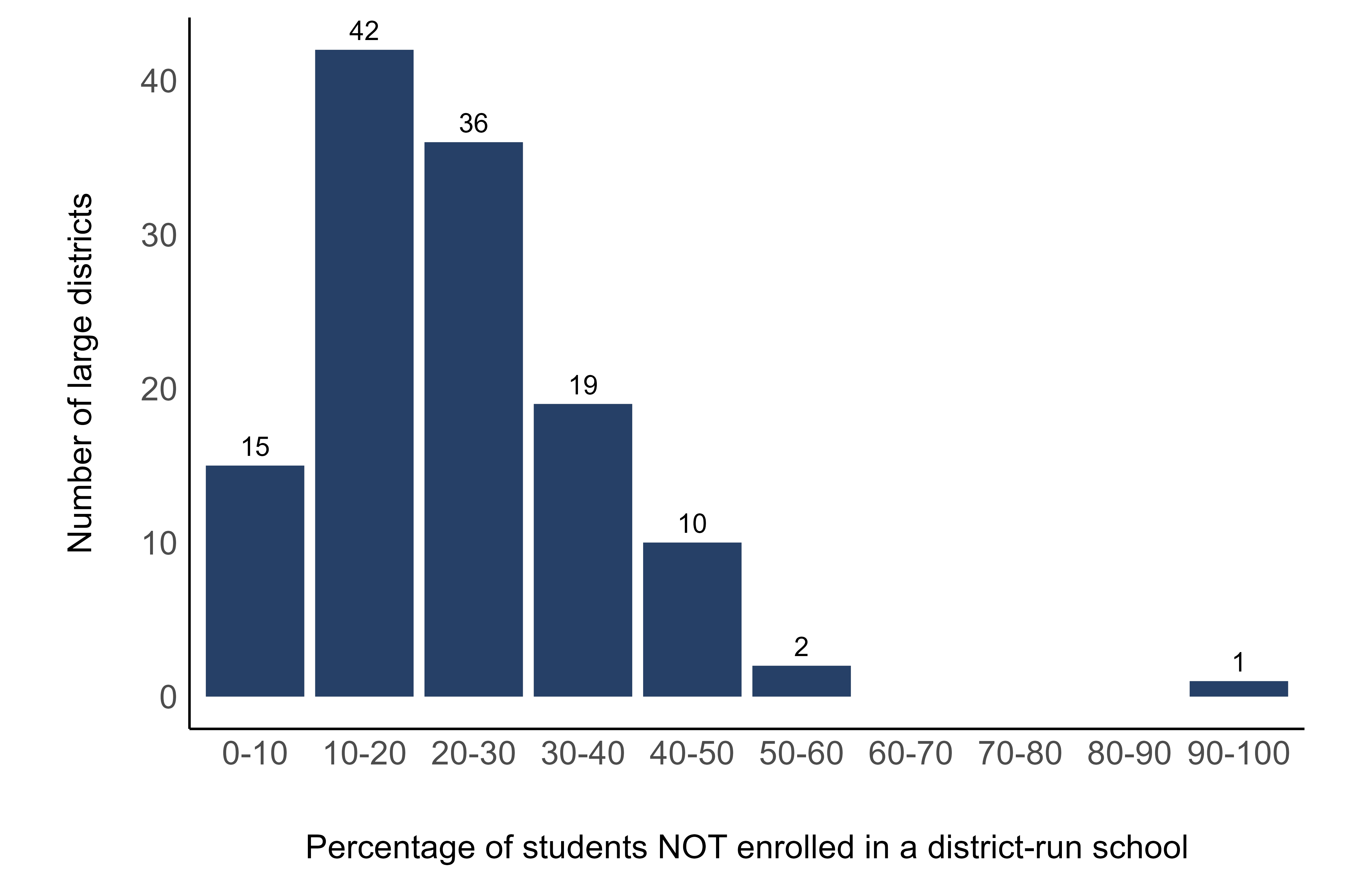

Within the 125 largest districts in the country, the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who were not enrolled in a district-run school in 2020 ranged from 5 percent to 100 percent; however, as Figure 3 illustrates, most large districts face only modest competition.

Figure 3: In most large districts, most students still enroll in district-run schools.

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of non-district competition in the largest 125 geographic school districts in the United States in 2020, as measured by the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who did not enroll in a district-run school.

Unsurprisingly, the country’s “most competitive large district” is the Orleans Parish School District, where there were no district-run schools by 2020 due to reforms implemented in the wake of Hurricane Katrina; however, per the figure, New Orleans remains a clear outlier, at least among the larger districts that are the focus of this study.

Per Table 1, in most places, the local education market looks more like those of Clayton County School District in Georgia and Corona-Norco Unified School District in California, which our estimates suggest are the country’s “least competitive large districts” and where approximately 95 percent of students enrolled in a district-run school in 2020. In the median large district, roughly four out of five students in grades 1-8 still enroll in a district-run school.

Table 1: Which large school districts face the most competition for students?

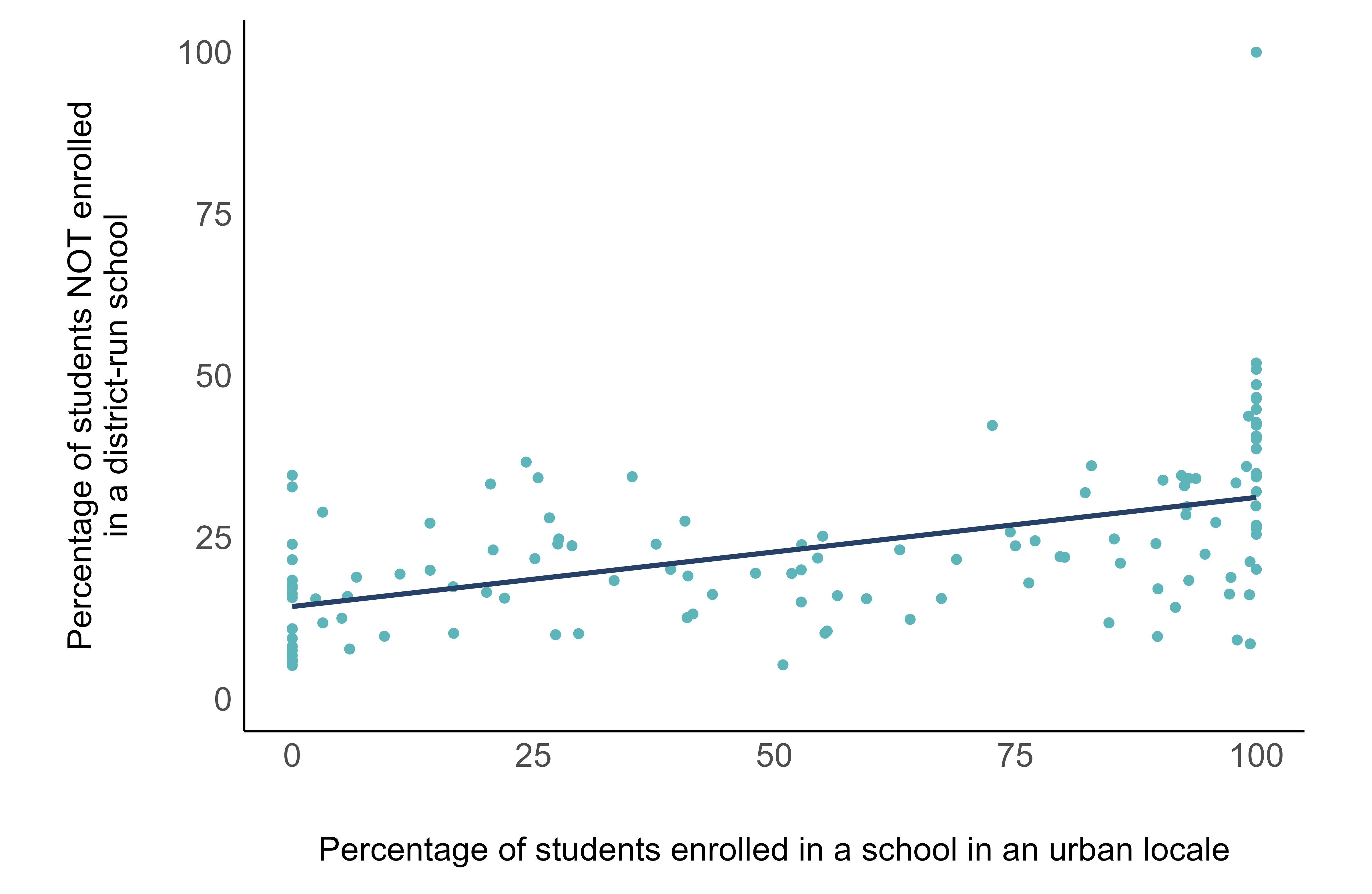

Notably, there is a moderate correlation between urbanicity and the percentage of students not enrolled in a district-run school (r = 0.49), with highly urban districts facing roughly twice as much competition on average as nonurban districts (Figure 4).

Figure 4: On average, urban districts face more competition for students than non-urban districts.

Notes: This figure shows the relationship between the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who attended a school in urban locale and the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who did not enroll in a district-run school in the largest 125 geographic school districts in the United States in 2020.

Given the practical barriers to greater competition in more rural areas, the urban focus of many reform efforts, and the comparatively strong performance of urban charter schools and private school choice programs, this relationship makes sense.

FINDING 2: BECAUSE NON-WHITE STUDENTS HAVE LESS ACCESS TO PRIVATE SCHOOLS, MOST LARGE DISTRICTS FACE MORE COMPETITION FOR WHITE STUDENTS

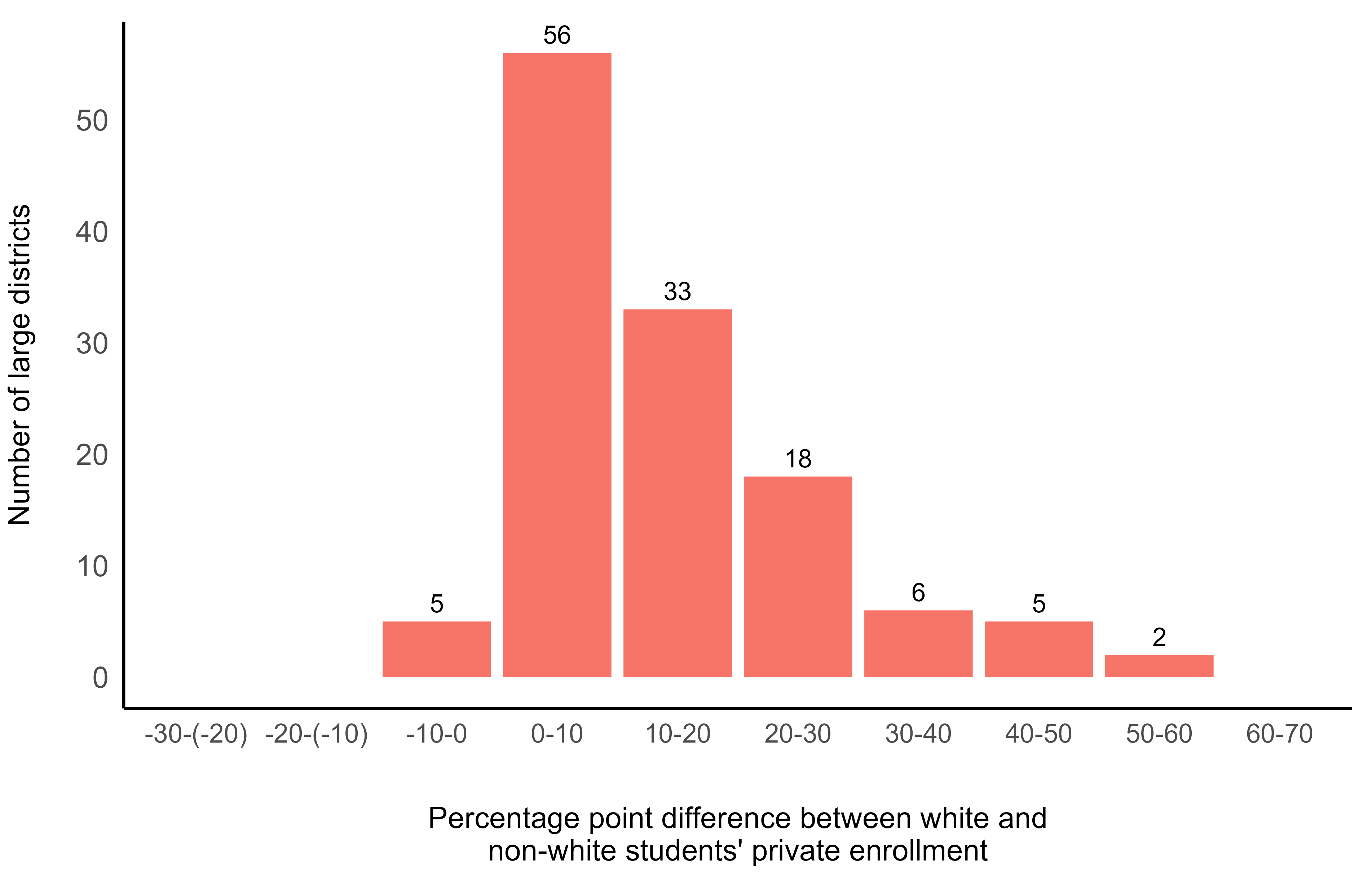

As of 2020, non-White students had less access to private schools than White students in every major school district in the United States, with the median district exhibiting a White/non-White gap of approximately fourteen percentage points (Figure 5).

Figure 5: In most large school districts, White students have more access to private schools than non-White students.

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of the White/non-White private school enrollment gap in grades 1–8 in the largest 125 school districts in the United States in 2020. Data on private school enrollment come from the Private School Universe Survey.

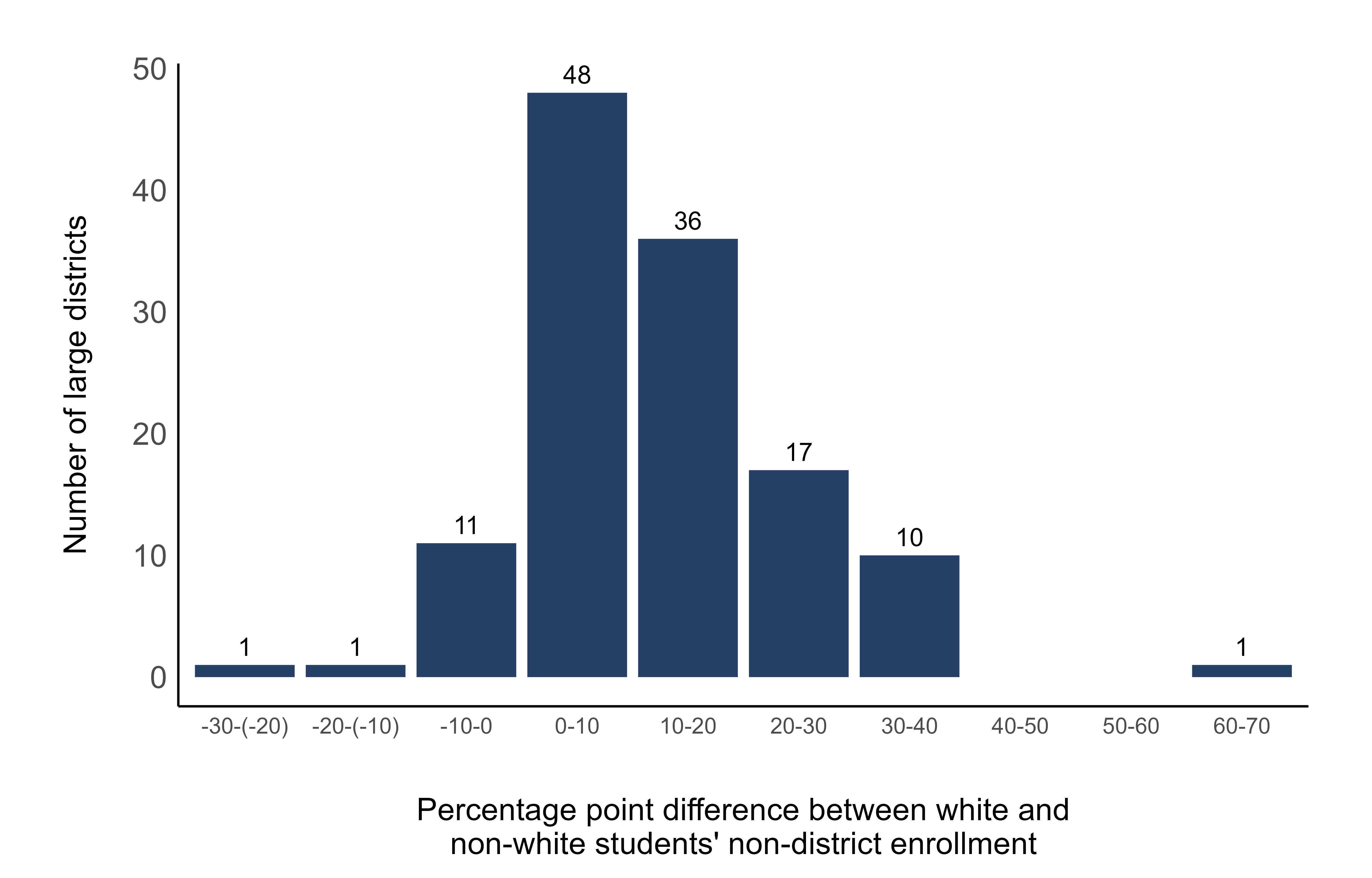

Similarly, White students were less likely to be enrolled in a district-run school than non-White students in 112 of the nation’s largest 125 districts, with the median district exhibiting a gap of about twelve percentage points (Figure 6).

Figure 6: Most large school districts face more competition for White students than non-White students.

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of the White/non-White “competitiveness gap” in the largest 125 geographic school districts in the United States as of 2020, as measured by the percentages of White and non-White students in grades 1–8 who did not enroll in a district-run school.

Per Table 2, the large school district with the biggest White/non-White “competitiveness gap” is Santa Ana Unified, where roughly 82 percent of White students were not enrolled in a district-run school in 2020 compared to just 17 percent of non-White students (a difference of 65 percentage points).

Table 2: Where is the gap between the competition districts face for White and non-White students largest?

Still, focusing exclusively on gaps threatens to obscure the bigger story in some districts. For example, despite having an unusually large competitiveness gap, San Antonio ranks second when it comes to the competition districts face for non-White students’ (see Table 3). And some districts have notably competitive markets for particular non-White subgroups. For example, about half of Milwaukee’s Hispanic students and roughly two-thirds of Atlanta’s Asian students are not enrolled in district-run schools.

Click on the column headings to see which districts face the most/least competition for students in the different racial/ethnic groups, as measured by the percentage of students NOT enrolled in a district-run school.

Table 3: Which large school districts face the most competition for students in different racial/ethnic groups?

FINDING 3: OVER THE LAST DECADE, MOST LARGE DISTRICTS FACED INCREASING COMPETITION, ESPECIALLY FOR NON-WHITE STUDENTS

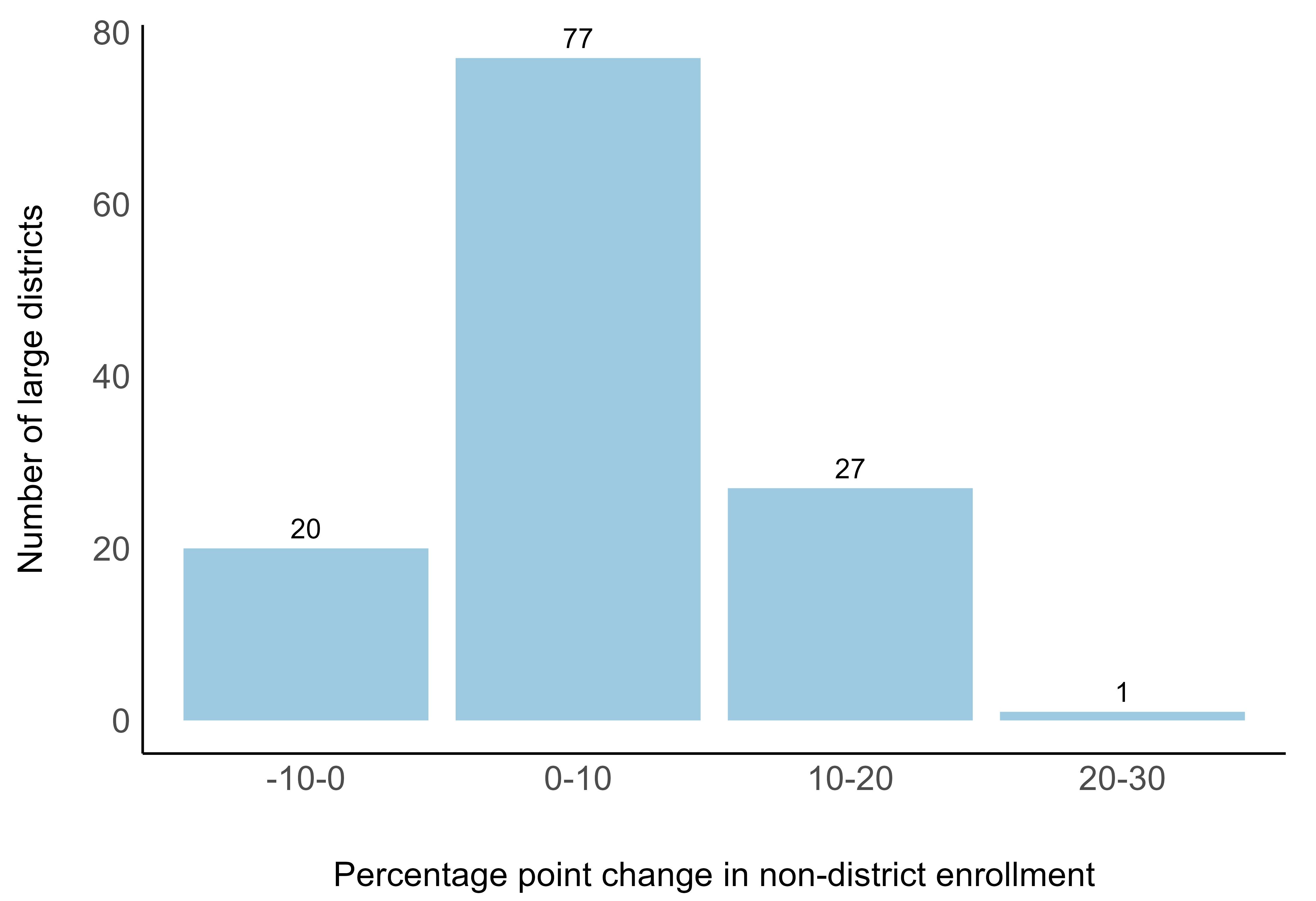

Of the country’s 125 largest school districts, 105 faced increasing competition for students between 2010 and 2020; however, in most cases, this increase was modest. In the typical large district, the share of students not enrolled in district-run schools increased by fewer than ten percentage points, and only one district saw an increase of more than twenty percentage points (Figure 7).

Figure 7: In most large districts, the share of students not enrolled in district-run schools increased modestly between 2010 and 2020.

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of the change in non-district enrollment in grades 1–8 in the largest 125 geographic school districts in the United States between 2010 and 2020.

Notes: This figure shows the distribution of the change in non-district enrollment in grades 1–8 in the largest 125 geographic school districts in the United States between 2010 and 2020.

Unsurprisingly, the district that experienced the biggest increase in competition was New Orleans, where the share of students not enrolled in a traditional public school increased from 75 percent to 100 percent between 2010 and 2020. In contrast, the share of students not enrolled in a traditional public school declined in Cincinnati (from 40 percent to 35 percent) and at least a dozen other major school districts (Table 4).

Table 4: Which large school districts saw the biggest increases in non-district enrollment?

Importantly, non-district enrollment increased more quickly among non-White students than it did among White students, with the typical large district seeing about a four-percentage-point increase among White students and a seven-percentage-point increase among non-White students. Of the 125 largest districts, 114 saw an increase in non-district enrollment among non-White students between 2010 and 2020, eighty-nine saw an increase among White students, and eighty-four saw an increase among both White and non-White students.

Finally, some districts saw notably rapid change for particular non-White subgroups. For example, Hispanic students’ non-district enrollment increased by twenty-three percentage points in Indianapolis. Places like Chandler, Arizona, saw even larger increases in Black students’ non-district enrollment. And in Douglas County, Colorado, Asian students’ non-district enrollment increased by forty-two percentage points.

Figure 8: How has competition for students in different racial/ethnic groups evolved in your school district?

Notes: This figure shows how the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who did not enroll in a district-run school changed within each of the major racial/ethnic subgroups between 2010 and 2020.

FINDING 4: IN MOST LARGE DISTRICTS, NEARLY ALL OF THE INCREASE IN COMPETITION FOR NON-WHITE STUDENTS WAS ATTRIBUTABLE TO THE GROWTH OF CHARTER SCHOOLS

Across and within the largest 125 districts in the country, the increase in charter school enrollment between 2010 and 2020 was responsible for most of the increase in competition during that same time period. For example, the dramatic increase in New Orleans’ overall competitiveness was driven by an inexorable increase in charter school enrollment. And the story in most other large districts is similar, especially for non-White students. In New York City, the increase in competition for Black students was entirely attributable to the growth of charter schools, as was the increase in competition for Hispanic students in Los Angeles and many other districts.

Figure 9: Which sector drove the increase or decrease in competition in your district and/or community?

Notes: This figure shows the percentage of students in grades 1–8 who enrolled in charter, private, or home schools between 2010 and 2020. Data on charter, private, and homeschool enrollment come from the Common Core of Data, the Private School Universe Survey, and the Family Involvement in Education Survey, respectively.

Takeaways

1. The death of traditional public schools has been greatly exaggerated.

Per Finding 1, the typical American student still attends a school that is administered by his or her local school district. And because the typical school district is only exposed to modest levels of competition, that school still has little incentive to change its behavior if that student is ill-served.

2. Most communities would benefit from the creation of more and/or more affordable non-district alternatives, especially for traditionally disadvantaged groups.

Per Finding 2, while the gap between White and non-White students’ access to non-district schooling has narrowed, it has not disappeared in most large districts. And despite the evidence that traditionally disadvantaged groups are particularly likely to benefit from non-district alternatives, the approach many places take to K–12 education policy is still reminiscent of that old and morally dubious adage: “Choice for me, but not for thee.”

3. Progress is possible.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, there is little to cheer when it comes to public education. Yet for advocates of equal opportunity and better schooling, the decade just before the pandemic was a time of real progress, at least when it came to the expansion of choice and competition in the communities served by our country’s largest school systems.

Let’s get back to that.

LIMITATIONS

The data that are the basis for this analysis are imperfect. For example, when it comes to charter schools, the fact that we don’t have students’ home addresses means we can’t definitively link them to the districts in which their schools are physically located (though, “competition” is arguably also about perception, which is necessarily impacted by the presence of non-district schools).

In the case of private schools, we are again limited by the absence of home addresses. Moreover, we are also limited by the fact that our data source is a survey, which means that approximately 20–30 percent of schools are missing (though we are at least partly addressing this problem by weighting for nonresponse).

Finally, when it comes to homeschooling and/or virtual schooling, we lack reliable district-specific data for most locations, and our estimates are perhaps better characterized as educated guesses. Fortunately, of the three types of competition, homeschooling is the least prevalent, so whatever error is baked into our estimates is unlikely to affect the overall story (see Technical Appendix).

In addition to these challenges, our analysis doesn’t account for interdistrict open enrollment, which research suggests is yet another salutary form of competition.[21] Nor does it capture the inevitable differences in districts’ responses to competition.

In short, the Index is a necessarily imperfect measure of competition, not the thing itself.

Technical Appendix

Table A1 shows the estimated percentages of students in grades 1-8 who were not enrolled in a traditional public school in the twenty-five ""large"" U.S. school districts where reliable district-level data on homeschooling enrollment could be located for the 2019-2020 school year with and without the inclusion of these data as opposed to Fordham's homeschooling enrollment estimates. Per the table, the official homeschooling data differ from Fordham's estimates for many of these districts (though in some cases, these differences are obscured by rounding). However, because homeschooling accounts for a modest share of total non-district enrollment, the implications for districts' overall competitiveness and ranks are modest (with the possible exception of Marion County's rank, which does change somewhat due to the number of districts with similar levels of competitiveness). Among other things, this suggests that the overall estimates and ranks of districts where official homeschooling data could not be located are close to the mark.

Table A1: Sensitivity Analysis

| Name | With district-reported homeschooling enrollment | With Fordham's estimates of homeschooling enrollment | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Non-District | Rank | % Non-District | Rank | |

| Boston School District | 34 | 22 | 36 | 18 |

| Brevard County School District | 27 | 38 | 26 | 43 |

| Charleston County School District | 23 | 56 | 24 | 50 |

| Cincinnati City School District | 34 | 25 | 35 | 19 |

| Cleveland Municipal School District | 44 | 8 | 45 | 8 |

| Columbus City School District | 36 | 17 | 37 | 16 |

| Dade County School District | 37 | 15 | 37 | 15 |

| Duval County School District | 33 | 29 | 32 | 31 |

| Fairfax County Public Schools | 12 | 101 | 13 | 99 |

| Henrico County Public Schools | 11 | 105 | 12 | 105 |

| Howard County Public Schools | 10 | 111 | 11 | 107 |

| Lake County School District | 33 | 30 | 30 | 33 |

| Lee County School District | 20 | 68 | 21 | 67 |

| Loudoun County Public Schools | 6 | 121 | 7 | 120 |

| Marion County School District | 18 | 79 | 16 | 92 |

| Milwaukee School District | 47 | 5 | 47 | 5 |

| Montgomery County Public Schools | 16 | 93 | 16 | 84 |

| New York City Department Of Education | 30 | 33 | 31 | 32 |

| Palm Beach County School District | 24 | 51 | 23 | 56 |

| Pasco County School District | 17 | 81 | 17 | 83 |

| Philadelphia City School District | 45 | 7 | 46 | 7 |

| Prince William County Public Schools | 6 | 123 | 7 | 121 |

| Seattle Public Schools | 26 | 42 | 27 | 40 |

| Virginia Beach City Public Schools | 8 | 116 | 9 | 115 |

ENDNOTES

[FW1]As of 2020, seventy-eight of the city’s eighty-six schools were overseen by the Orleans Parish School Board and New Orleans-Public Schools (NOLA-PS). According to the Cowen Institute, all but three of these schools are independent public charter schools; NOLA-PS does not directly run any of the schools under its purview. See https://cowendata.org/reports/the-state-of-public-education-in--new-orleans-2019/governance.

[1] Deven Carlsen, Open Enrollment and Student Diversity in Ohio’s Schools (Columbus, OH: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2021) https://fordhaminstitute.org/ohio/research/open-enrollment-and-student-diversity-ohios-schools.

[2] Huriya Jabbar et al., “The competitive effects of school choice on student achievement: A systematic review,” Educational Policy 36, no. 2 (2022): 24–81, https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904819874756; and Jeffrey Max et al., “How Does School Choice Affect Student Achievement in Traditional Public Schools?” (education issue brief, Mathematica Policy Research, Princeton, NJ, 2019), https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:mpr:mprres:b36d8f1911714dd68ceac8a3e52c1ca2.

[3] George M. Holmes, Jeff DeSimone, and Nicholas G. Rupp, “Does School Choice Increase School Quality?” (working paper no. 9683, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2003), https://www.nber.org/papers/w9683; Tim R. Sass, “Charter schools and student achievement in Florida,” Education Finance and Policy 1, no. 1 (2016): 91–122, https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp.2006.1.1.91; Kevin Booker et al., “The effect of charter schools on traditional public school students in Texas: Are children who stay behind left behind?” Journal of Urban Economics 64, no. 1 (2008): 123–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2007.10.003; Hiren Nisar, “Heterogeneous competitive effects of charter schools in Milwaukee” (draft, Abt Associates Inc, 2012), https://ncspe.tc.columbia.edu/working-papers/files/OP202.pdf; Yusuke Jinnai, “Direct and Indirect Impact of Charter Schools’ Entry on Traditional Public Schools: New Evidence from North Carolina,” Economics Letters 124, no. 3 (2014): 452–56, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.07.016; Sarah A. Cordes, “In Pursuit of the Common Good: The Spillover Effects of Charter Schools on Public School Students in New York City,” Education Finance and Policy 13, no. 4 (2018): 484-512, https://doi.org/10.1162/edfp_a_00240; Mavuto Kalulu, Morgan Burke, and Thomas Snyder, “Charter School Entry, Teacher Freedom, and Student Performance,” eJEP: eJournal of Education Policy 21, no. 1 (2020): n1; Nirav Mehta, “Competition in public school districts: charter school entry, student sorting, and school input determination,” International Economic Review 58, no. 4 (2017): 1089–116; Matthew Ridley and Camille Terrier, “Fiscal and Education Spillovers from Charter School Expansion,” Journal of Human Resources (2023), https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.0321-11538R2; Michael Gilraine, Uros Petronijevic, and John D. Singleton, “Horizontal differentiation and the policy effect of charter schools,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 13, no. 3 (2021): 239–76; Niu Gao and Anastasia Semykina, “Competition effects of charter schools: New evidence from North Carolina,” Journal of School Choice 15, no. 3 (2021): 393–416; and David N. Figlio, Cassandra M. D. Hart, and Krzysztof Karbownik, “Competitive Effects of Charter Schools” (conference paper, 6th IZA Workshop: The Economics of Education, 2021), https://conference.iza.org/conference_files/edu_2021/karbownik_k7512.pdf.

[4] Matthew Carr and Gary Ritter, Measuring the Competitive Effect of Charter Schools on Student Achievement in Ohio’s Traditional Public Schools (Fayetteville, AR: University of Arkansas, 2007); Yongmei Ni, “The impact of charter schools on the efficiency of traditional public schools: Evidence from Michigan,” Economics of Education Review 28, no. 5 (2009): 571–84; and Scott A. Imberman, “The effect of charter schools on achievement and behavior of public school students,” Journal of Public Economics 95, no. 7–8 (2011): 850–63.

[5] Another seven studies find null or mixed effects: Eric P. Bettinger, “The effect of charter schools on charter students and public schools,” Economics of Education Review 24, no. 2 (2005): 133–47; Robert Bifulco and Helen F. Ladd, “The impacts of charter schools on student achievement: Evidence from North Carolina,” Education Finance and Policy 1, no. 1 (2006): 50–90; Ron Zimmer and Richard Buddin, “Is charter school competition in California improving the performance of traditional public schools?” Public Administration Review 69, no. 5 (2009): 831–45; Ron Zimmer et al., Charter Schools in Eight States: Effects on Achievement, Attainment, Integration, and Competition (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2009), https://www.rand.org/pubs/monographs/MG869.html; Marcus A. Winters, “Measuring the effect of charter schools on public school student achievement in an urban environment: Evidence from New York City,” Economics of Education Review 31, no. 2 (2012): 293–301; Edward J. Cremata and Margaret E. Raymond, “The competitive effects of charter schools: Evidence from the District of Columbia” (conference working paper, Association for Education Finance and Policy, 2014); Joshua Horvath, “Charter School Effects on Charter School Students and Traditional Public School Students in North Carolina” (doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC, 2018), https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/dissertations/mw22v616b.

[6] Betts, Julian R., and Y. Emily Tang. "The effect of charter schools on student achievement." School choice at the crossroads: Research perspectives (2018): 67-89.

[7] Margaret Raymond, James Woodworth, Won Fy Lee, and Sally Bachofer, As a Matter of Fact: The National Charter School Study III (Stanford, CA: Center for Research on Education Outcomes, 2023), https://ncss3.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Credo-NCSS3-Report.pdf.

[8] David Griffith, Rising Tide: Charter School Market Share and Student Achievement (Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2019), https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/rising-tide-charter-market-share; David Griffith, Still Rising: Charter School Enrollment and Student Achievement at the Metropolitan Level (Washington, D.C.: Thomas B. Fordham Institute, 2022), https://fordhaminstitute.org/national/research/still-rising-charter-school-enrollment-and-student-achievement-metropolitan-level; Feng Chen and Douglas N. Harris, The Combined Effects of Charter Schools on Student Outcomes: A National Analysis of School Districts (New Orleans, LA: National Center for Research on Education Access and Choice, 2021), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED622023.pdf.

[9] Max et al., “How Does School Choice Affect Student Achievement in Traditional Public Schools?”

[10] Matthew Carr, “The Impact of Ohio’s EdChoice on Traditional Public School Performance,” CATO Journal 31, no. 2 (2011): 257–84; Rajashri Chakrabarti, “Impact of Voucher Design on Public School Performance: Evidence from Florida and Milwaukee Voucher Programs,” FRB of New York Staff Report No. 31572 (January 2008), http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1086772; Rajashri Chakrabarti, “Vouchers, Public School Response, and the Role of Incentives: Evidence from Florida,” Economic Inquiry 51, no. 1 (2013): 500–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00455.x; David Figlio and Cassandra M. D. Hart, “Does Competition Improve Public Schools? New Evidence from the Florida Tax-Credit Scholarship Program,” Education Next 11, no. 1 (2011): 74–80, https://www.educationnext.org/does-competition-improve-public-schools; Nathan L. Gray, John D. Merrifield, and Kerry A. Adzima, “A Private Universal Voucher Program’s Effects on Traditional Public Schools,” Journal of Economics and Finance 40, no. 1 (2016): 319–44, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-014-9309-z; Jay P. Greene and Ryan H. Marsh, The Effect of Milwaukee’s Parental Choice Program on Student Achievement in Milwaukee Public Schools (SCDP Comprehensive Longitudinal Evaluation of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program, Report #11, School Choice Demonstration Project, Fayetteville, AR, 2009), https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED530091.pdf; Jay P. Greene and Marcus A. Winters, “When Schools Compete: The Effects of Vouchers on Florida Public School Achievement,” (education working paper, Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute, New York, NY, 2003), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED480754; Anna J. Egalite and Jonathan N. Mills, “Competitive impacts of means-tested vouchers on public school performance: Evidence from Louisiana,” Education Finance and Policy 16, no. 1 (2021): 66–91; Jay P. Greene, An evaluation of the Florida A-Plus accountability and school choice program (New York, NY: Center for Civic Innovation at the Manhattan Institute, 2001), https://media4.manhattan-institute.org/pdf/cr_aplus.pdf; David N.Figlio and Cecilia Elena Rouse, “Do accountability and voucher threats improve low-performing schools?” Journal of Public Economics 90, no. 1–2 (2006): 239–55; Martin R. West and Paul E. Peterson, “The efficacy of choice threats within school accountability systems: Results from legislatively induced experiments,” The Economic Journal 116, no. 510 (2006): C46–C62; Greg Forster, Lost Opportunity: An Empirical Analysis of How Vouchers Affected Florida Public Schools. School Choice Issues in the State (Indianapolis, IN: Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, 2008); Cecilia Elena Rouse et al., “Feeling the Florida heat? How low-performing schools respond to voucher and accountability pressure,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5, no. 2 (2013): 251–81; David Figlio and Cassandra M. D. Hart. “Competitive effects of means-tested school vouchers,” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6, no. 1 (2014): 133–56; Marcus A. Winters and Jay P. Greene, “Public school response to special education vouchers: The impact of Florida’s McKay Scholarship Program on disability diagnosis and student achievement in public schools,” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33, no. 2 (2011): 138–58; Amita Chudgar, Frank Adamson, and Martin Carnoy, Vouchers and Public School Performance: A Case Study of the Milwaukee Parental Choice Program (Washington, D.C.: Economic Policy Institute, 2007); Greene and Marsh, The Effect of Milwaukee’s Parental Choice Program on Student Achievement in Milwaukee Public Schools; Jay P. Greene and Greg Forster, “Rising to the Challenge: The Effect of School Choice on Public Schools in Milwaukee and San Antonio,” (civic bulletin, Manhattan Institute, New York, NY, 2002); Rajashri Chakrabarti, “Can increasing private school participation and monetary loss in a voucher program affect public school performance? Evidence from Milwaukee,” Journal of Public Economics 92, no. 5–6 (2008): 1371–93; and Greg Forster, Promising Start: An Empirical Analysis of How EdChoice Vouchers Affect Ohio Public Schools. School Choice Issues in the State (Indianapolis, IN: Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice, 2008), https://www.edchoice.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Promising-Start-How-EdChoice-Vouchers-Affect-Ohio-Public-Schools.pdf.

[11] M. Danish Shakeel, Kaitlin P. Anderson, and Patrick J. Wolf, “The participant effects of private school vouchers around the globe: A meta-analytic and systematic review,” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 32, no. 4 (2021): 509–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2021.1906283.

[12] Leesa M. Foreman, “Educational attainment effects of public and private school choice,” in School Choice: Separating Fact from Fiction, ed. Patrick J. Wolf (New York, NY: Routledge, 2019), 156–68. Figlio, Hart, and Karbownik, “Competitive Effects of Charter Schools.”

[13] More specifically, we exclude “fully” and “primarily” virtual schools.

[14] To achieve a nationally representative sample, NCES assigns a handful of “Area Frame” schools higher base weights in the first year in which they are identified; however, while these weights are appropriate from a national perspective, they are potentially inappropriate from the perspective of an individual district. Consequently, for the purposes of the district-specific estimates, we reweighted “Area Frame” schools based on the average weight that was assigned to the more numerous “List Frame” schools nationally in the school year in question.

[15] Specifically, for the 2012 through 2018 school years, we took a simple average of the values (including interpolated values) for times t-2 through t+2. For the 2011 and 2019 school years, we averaged the values for 2010–13 and 2017–20, respectively. Finally, for the 2010 and 2020 school years (i.e., the first and last years of our study period), we averaged the values for 2010–12 and 2018–20.

[16] The two states where we decided against using the official data are Colorado (where official counts are likely too low because sufficiently motivated parents can band together to form “nonpublic” schools) and North Carolina (where the official numbers are likely inflated because parents are only required to register once, meaning there are defunct homeschools that are still on the books). In three of the remaining ten states (Maryland, Virginia, and Wisconsin), the official data were available for all eleven years of the study period; however, in the other seven states (Florida, Massachusetts, Ohio, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, New York, and Washington), publicly available data were missing for one or more (typically older) years. So, to fill in these blanks, we used the official numbers for the nearest school year for which data were available (for example, we used Boston’s 2010–11 homeschooling enrollment for both that year and for 2009–10). Although it was often unclear when data collection occurred for homeschooling, our impression is that most large districts’ 2019–20 data were relatively unaffected by the arrival of the pandemic, with the notable exception of New York City (where there is an unusually sharp increase between 2018–19 and 2019–20). So, after some consideration, we decided to substitute New York City’s 2018–19 numbers for its 2019–20 numbers and stick with the 2019–20 numbers for the other large districts. Finally, because most states don’t break their district-level homeschooling numbers down by grade level, to align the official K–12 numbers with our estimates for grades 1–8, we multiplied the K–12 counts by 8/13 (which seems reasonable, given that homeschooling rates exhibit little variation across grade levels). To generate equivalent district-specific estimates for racial subgroups, we adjusted the district-specific estimates for “all students” based on our estimates of the relevant subgroups’ national homeschooling rates.

[17] For example, the national data suggest that homeschooling declined in 2016–19, despite the fact that many state and district-level counts increased.

[18] Specifically, we took the following steps: First, to estimate the national homeschooling rates for White, Black, Hispanic, Asian, and “other” students in grades 1-8, we divided the national homeschooling rates for each of those groups (in all grade levels and waves) by the national homeschooling rate for all students (again, in all grade levels waves) and multiplied the resulting ratios by the national average for all students in grades 1-8. We then used a similar process to estimate the national homeschooling rates for urban, suburban, town, and rural students in grades 1-8. We then calculated race-adjusted homeschooling rates for each school district by taking weighted averages of the relevant national estimates for White, Hispanic, Black, Asian, and “other” students based on the percentages of students in a district’s public and private schools who belonged to each group. We then used a similar process to calculate location-adjusted homeschooling rates for each school district based on the percentages of students who attended schools that were classified as urban, suburban, town, or rural. Finally, to ensure that we were taking both race and location into account, we multiplied the race- and location-adjusted estimates for each school district and divided the result by the national estimate for all students in grades 1-8.

[19] Lauraine Langreo, “Charter School Enrollment Holds Steady After Big Early Pandemic Growth,” Education Week, November 30, 2022, https://www.edweek.org/policy-politics/charter-school-enrollment-holds-steady-after-big-early-pandemic-growth/2022/11.

[20] Thomas S. Dee, “Where the Kids Went: Nonpublic Schooling and Demographic Change during the Pandemic Exodus from Public Schools” (brief, Urban Institute, Washington, D.C., February 9, 2023), https://www.urban.org/research/publication/where-kids-went-nonpublic-schooling-and-demographic-change-during-pandemic.

[21] Babington, M., and D.M. Welsch. “Open Enrollment, Competition, and Student Performance.” Journal of Education Finance, vol. 42, 2017, pp. 414–434. Welsch, D.M., and D.M. Zimmer. “Do Student Migrations Affect School Performance? Evidence from Wisconsin’s Inter-District Public School Program.” Economics of Education Review, vol. 31, 2012, pp. 195–207.

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible through the generous support of the Charter School Growth Fund, as well as our sister organization, the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. We are deeply grateful to Emily Gutierrez at the Urban Institute, who reviewed an early draft of the report, and to Pamela Tatz for copyediting.

On the Fordham side, we are grateful to Griffith and Luna for authoring the report, to Adam Tyner for developing the report’s interactive data elements, to Chester E. Finn, Jr. for providing feedback on drafts, to Stephanie Distler for managing report production and design, and to Victoria McDougald for overseeing media dissemination.