In the wake of Donald Trump’s election and his selection of Betsy DeVos as Education Secretary, a lot of attention has been focused on school choice. Though charters and vouchers have received the lion’s share of attention, there’s another under-the-radar school choice program that impacts thousands of students: interdistrict open enrollment, a policy that permits students to attend school in a district other than the one in which they live.

Though Ohio’s program was one of the nation’s earliest, limited information has been available about who participates and how they perform academically. To shed some light on this important program, we commissioned a report: Interdistrict Open Enrollment in Ohio: Participation and Student Outcomes. On June 6, we hosted an event to present the findings and to learn more about how the policy works in practice.

Opening the event was Dr. Deven Carlson, a professor from the University of Oklahoma and one of the report’s co-authors. Carlson began by overviewing Ohio’s open enrollment program. (His slide deck is available here.)

Report co-author Deven Carlson presents findings

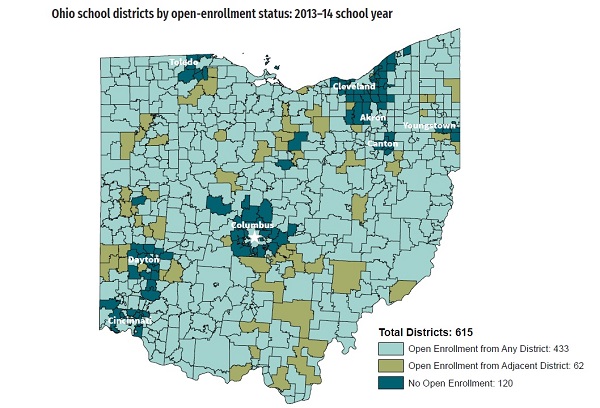

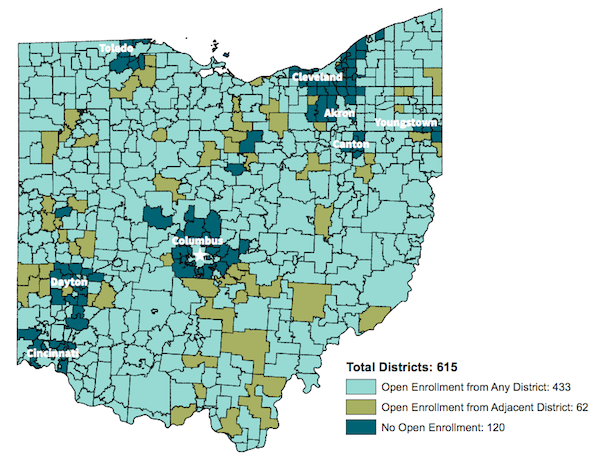

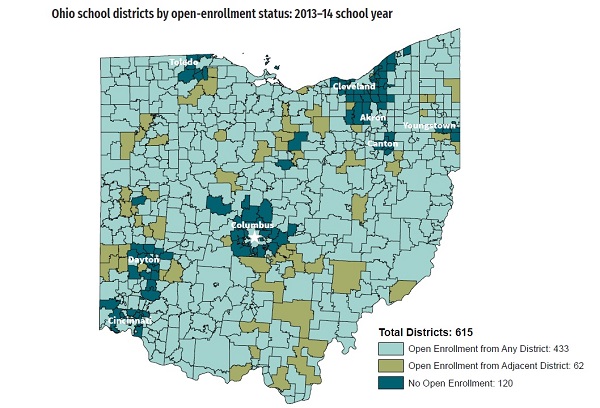

In regards to district participation, Carlson noted that a large and growing majority of Ohio districts are choosing to take part—statewide, 73 percent of districts accept students from any district and 8 percent from adjacent ones. The districts that choose not to participate are largely clustered in the suburbs around Ohio’s Big Eight school districts.

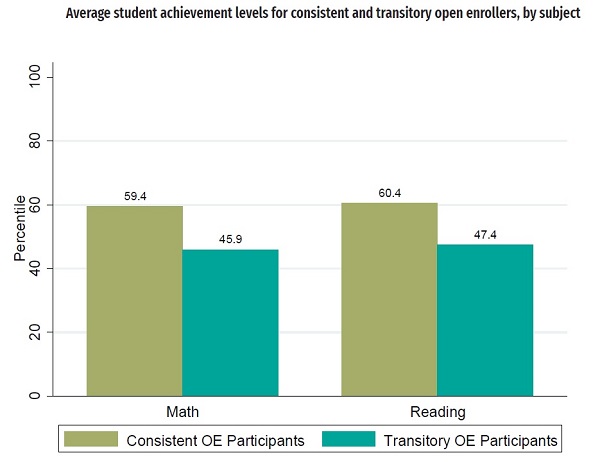

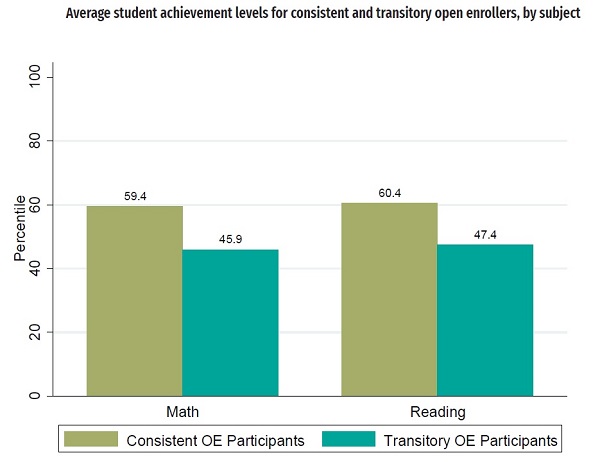

Student participation, meanwhile, has grown from about 50,000 students during the 2008-09 school year to nearly 72,000 in 2013-14. Compared to students who attend their resident districts, students who open enroll are less likely to be economically disadvantaged and somewhat higher achieving. As for participation by race, black students tend to participate at lower rates, though they also have less of an opportunity to open enroll than their white peers due to district participation decisions.

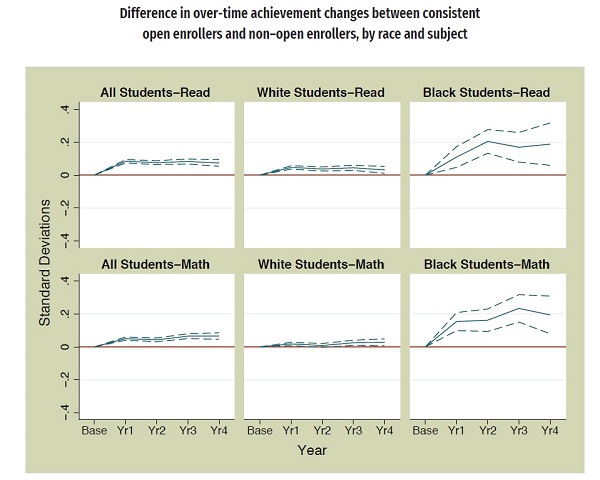

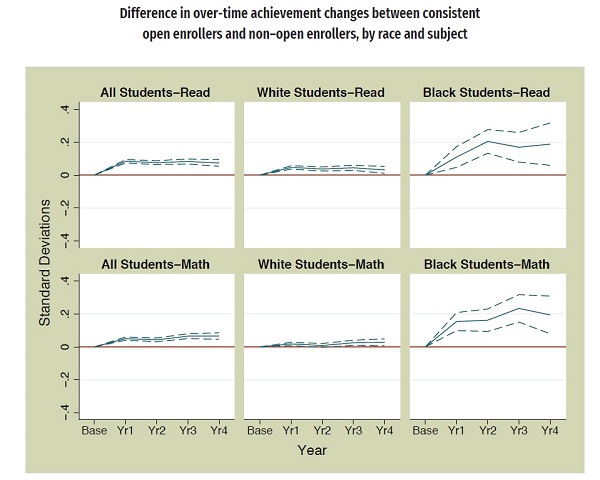

When considering the achievement growth of consistent open enrollers, Carlson reported that they perform about as well as they did prior to transferring. Yet when consistent open enrollers are compared to those who never open enroll, academic gains emerge. Carlson noted that this suggests that while open enrollers don’t exhibit substantial gains relative to their own baseline test scores, they don’t face the declines that non-open enrollers appear to experience. These gains are largest for black students and students in high-poverty urban and rural areas.

To complement the research presentation, three on-the-ground panelists shared their experiences and thoughts on Ohio’s open enrollment program. They included Tina Thomas-Manning, Superintendent of Reynoldsburg City Schools (adjacent to Columbus); Geno Thomas, Superintendent of Lowellville Local Schools (near Youngstown); and Gadah Hamad, a Central Ohio parent whose daughter has benefited immensely from the program.

When asked why their districts chose to participate in open enrollment, Thomas-Manning explained that Reynoldsburg initially did so based on “selfish” reasons. “We found ourselves in a pretty weak situation where we had a lot of space in some of our school buildings, and our enrollment appeared to be declining,” she said. “We had a lot of space and we wanted to utilize that space and we thought this policy would be a very creative way to provide access to students outside our district and fill classrooms.” She emphasized that overall, the policy has been “very good for kids and has been good for our school district.”

Panelists Deven Carlson, Geno Thomas, Tina Thomas-Manning, and Gadah Hamad

Thomas, meanwhile, pointed out that Lowellville is a small district—it currently enrolls around 600 students in grades K-12. Open enrollment has increased the population of the district and thus the type of opportunities they can offer to students, but it’s also improved the district in other ways—namely by expanding its diversity. “We’re very happy with open enrollment,” Thomas said. “It’s not a funding issue. It does help our schools, but it’s much deeper than just the funds.”

Thomas also referenced research done a few years ago in Mahoning County, where his district is located. “Part of the study was spurred because Youngstown was put into academic distress,” he explained. People “wanted to see if open enrollment truly did make on impact on students that traveled from one district to another.” Open enrollment turned out to matter immensely for the Mahoning County students who chose to take advantage of it. “We have about 135 to 140 students from Youngstown City Schools that come to Lowellville,” Thomas explained. “Those students are performing if not equal to then better than our resident students and the overall population of all students, and significantly outperforming other students in the Youngstown City Schools.” Thomas also addressed an argument made by choice opponents, which accuses choice-related programs of “creaming” students. “People might say well, you got the good kids from Youngstown,” he said. “That’s an insult. These kids are academically or economically disadvantaged, multicultural, from broken homes and single-family homes, and there are transient and transportation issues that we face daily.”

Thomas-Manning echoed the sentiment that open enrollment had proved beneficial for students within and outside her district. “We find each year, and have for the past seven years, that our open enrollees are students who are keeping pace, or in some instances […] outperforming our resident students.” She emphasized that to date, Reynoldsburg has found no evidence that opening their district borders has had a negative impact on its performance. “We truly embrace the idea that these are our kids,” she said.

For Hamad, Reynoldsburg’s accepting attitude was a big part of the reason she open enrolled her daughter there. “It was something that was very beneficial for my family,” she explained. “It was a location where I could get the best of both words.” When asked about the challenges of open enrollment, Hamad had some key insights. “I don’t work. So for me, I dedicated my whole day and my life to my kids. Anything they wanted to do education wise, I supported them,” she said. “But I think for other parents, that’s a big problem. Because if it’s going to be between a mom getting to her job or sending her kid to the local school because the bus stop is across the street, then I see where she’s going to go. She’s not going to be able to send her kid across town, especially in rush hour.”

Both superintendents agreed that transportation is a significant challenge for interested families. “We have found, by and large, that transportation is a huge barrier,” Thomas-Manning shared. “Particularly for our younger students who are not in charge of driving themselves to school.” Thomas pointed out that although resident districts must provide transportation or transportation vouchers for students who choose to attend charter or parochial schools, there is no such benefit for families who decide to transfer from one public district to another.

The panelists’ final statements revolved around opportunity and access. “Everyone wants to have a voice,” Hamad shared. “Everyone wants freedom. Freedom of speech, freedom to choose, freedom of everything. But I think that the freedom to pick your education is one of the most important. This is what shapes the children.” She nodded in the direction of her daughter, who was sitting in the audience. “She found herself. And every child should have the right. I don’t think that should be taken away.”

Thomas-Manning agreed that it’s important for families to have the right to choose. When families “choose us, that’s wonderful,” she said. “There’s no greater vote of confidence.”